By John Helmer in Moscow

|

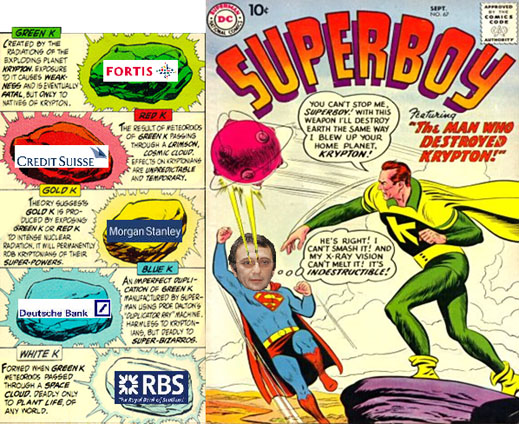

This report is powered by kryptonite!

|

Suleiman Kerimov is the most silent of the Russian oligarchs. As a deputy of the State Duma, between 1999 and 2007, the parliamentary archive is empty of records that he made a speech or cast a vote. His office in those years was headed by Alexey Krasovsky, who on January 25, 2007, said that Kerimov had appeared in the Duma in the morning of the day before, and had a cup of tea, before starting work.

Since February 20, 2008, when Kerimov took his seat as a senator in the upper house, the Federation Council, the records are equally blank. Kerimov’s senatorial office has a telephone number, which rings during business hours without being answered. He belongs to the Council’s Committee on Financial Markets. Krasovsky the spokesman, who answers a mobile telephone, says: “Kerimov is always actively participating in the Committee’s work”. But he does not give a date for the last time Kerimov attended a committee meeting. Asked if there had been an accomplishment on the committee for which Kerimov deserves credit, he didn’t mention one. “Information about Kerimov is none of your business”, Krasovsky said.

It would certainly be true that information about Kerimov is none of anyone’s business, if he were not a member of parliament with a public constituency; and also a controlling shareholder of the London-listed public shareholding company, Polyus Gold, Russia’s leading goldminer. Just because he’s rich – the Forbes listing for 2008 put his worth at $17.5 billion, but that was on paper, before the crash – he has no obligation to give interviews. And he hasn’t. He is the only oligarch not to be a member of the Russian Union of Enterpreneurs and Industrialists. His presence at meetings between the oligarchs and the Russian President and Prime Minister has not been reported.

Once, Kerimov did concede that selling shares to public investors, which he owned in Polymetal, the second of Russia’s goldmining companies, obliged him to make public disclosures. But that provided only a brief glimpse in the risk section of Polymetal’s prospectus at the London Stock Exchange. The disclosures hinted at a general problem with analyzing Kerimov’s business – is he acting alone as sole proprietor, or does he represent silent partners with at least as large a stake in his transactions as he is believed to have? Does he leverage his best-known asset purchases, and if so, what is his net position when they are valued or sold?

For example, the Polymetal investment prospectus, dated January 24, 2007, ran to more than 500 pages, and was drafted by Merrill Lynch in London. The auditor identified was PriceWaterhouseCoopers. According to ambiguous wording in the text, the prospectus revealed the possibility that, although Kerimov had been reported to be the 100% owner of Polymetal – having paid $930 million of borrowed funds for it in 2006 – at IPO a year later, there might have been two other stakeholders, who together owned 75%, the controlling interest in Polymetal, leaving Kerimov with just 25%. The reason for the ambiguity was that there was no telling who the beneficial owners were of the companies identified as holding Polymetal’s shares after the takeover, but before the listing.

“Any event or circumstance,” recorded the prospectus at page 21, “affecting Mr. Kerimov as a natural person, such as divorce, incapacity or death, may have an impact on the control over, and ownership of his interest in, the Company, or may lead to a change of control of the Company.” This was an unusual acknowledgement. Firuza Kerimov (FK) had been identified in a Moscow newspaper as Kerimov’s wife of approximately 20 years at the time; she was also reported as the founder, or co-founder, of FK Capital. Through this company, the prospectus conceded, the buyout of Polymetal from the ICT group of Alexander and Vitaly Nesis was done in late 2005.

The reference in the Merrill Lynch text was an unprecedented one in Russian corporate flotations then, suggesting that Kerimov’s real stake was shared equally with his wife, and that if the latter were to opt out of the marriage, she could force a disposal sale.

|

What was also unclear from the section in the prospectus entitled “Principal and Selling Shareholder” was who else, in addition to Mrs Kerimov, might have had an interest in the Polymetal asset. According to the text, at page 140, the selling shareholder to the London market, with 275 million Polymetal shares (100%), was Nafta Moskva (Cyprus) Limited. It was incorporated on March 20, 2006, after Kerimov bought Polymetal. Kerimov’s purchase transaction, according to the Polymetal recital, began in November 2005, when he bought 50% of the goldminer’s shares through Nafta Moskva in Moscow, or FK Capital in Moscow, which are interlocking, and controlled by Mr and Mrs Kerimov. |

At the same time, the prospectus revealed, “an unrelated party purchased a 50% beneficial interest in Polymetal’s share capital through an affiliate of Nafta Moskva (Cyprus) Limited.” Since the latter did not legally materialize for another five months, it is unclear what was happening, or who the “unrelated party” was, participating in the acquisition. If the “unrelated party” owned 50%, and Mrs Kerimov a half-share of the balance, then Suleiman turned out to be the proprietor of just 25%.

It is also unclear what happened when the unidentified affiliate of Nafta Moskva Cyprus “repurchased such beneficial interest on 19 April 2006.” Was the “unrelated party” cashing out at this point, or was he converting a “direct” stake into an indirect one, through a trusteeship vested in the newly created Cyprus front company?

According to the prospectus, “Mr Kerimov indirectly beneficially owns 99.5% of the Company’s Ordinary Shares.” However, the wording implies he did so with his wife’s share, and that he might also have done so through a trustee arrangement with the “unrelated party”.

The ambiguities of who owned Polymetal became a historical curiosity in June 2008, when Kerimov sold out of Polymetal. More accurately, it was reported that Kerimov had sold his 68% stake in Polymetal, through a vehicle called Aniketa Investments, to Alexander Nesis (24.05%), the former and founding owner; Peter Kellner, the Czech magnate (24.9%); and a Moscow banker, Alexander Mamut (19.05%). Polymetal financial reports suggest that since the London listing in 2007, there has been a 25% free float, and the balance of 7%, treasury shares owned by the company.

In the 30 months between Kerimov’s buy-in and exit, Polymetal managed to generate net income for only one year – in 2006, this was $61.7 million. In 2007, this turned to a bottom-line loss of $22.8 million. In 2008, the loss was $15.7 million. At December 30, 2008, Polymetal as a going concern reported $44.8 million more in liabilities than the value of its assets. Sberbank, which, according to the sellers, had loaned Kerimov the money to buy Polymetal, was also the largest lender to the company itself, accounting for almost half of its $223 million in long-term debt. Under its loan conditions, Sberbank took most of the gold and silver the company produced for sale.

No dividends appear to have been issued when Kerimov was the proprietor. But for his mid-2008 sale of Polymetal shares, Kerimov was reported to have been paid about $2 billion. That suggests a profit on his entry price of $1.1 billion.

|

What happened to that cash is quite unknown. What is thought, according to market sources and published speculation, is that during the first half of 2008 Kerimov liquidated his major Russian stockholdings, including Polymetal, Gazprom, and Sberbank. If as speculated, Kerimov held 4% of Gazprom, and if his timing was lucky, the sale might have realized about $11 billion. And if he held 6% of Sberbank stock, that disposal, if fortunate, would have generated more than $4 billion. So, adding up the estimated cash value of the three deals in the first half of 2008, Kerimov might have earned more than $16 billion. With retrospective vision after the collapse of Russian share prices and corporate income, this was a Superboy feat, indeed! |

What happened next is also not known, since it falls into the category of what Kerimov’s parliamentary spokesman calls “none of your business”. That Gazprom and Sberbank are publicly traded shareholding companies, with state reporting obligations, makes no difference.

The speculation is that from the very large number, Kerimov was obligated to pay off the loans which had financed the share-buying in the first place. That appears to be certain, but the value of the debt is unknown. About $4 billion, or 25% of the liquidation, can be estimated to have gone on repayment of credits. That ought to have left $12 billion for distribution; but much less sure is the guesswork of how many silent partners there were in Kerimov’s syndicate, and what entitlements they had to a share of this aggregate, if any. Perhaps Kerimov himself netted less than a third; that would have been about $3 billion.

Whether that number is more or less than accurate, what happened next, according to European banking sources, is that Kerimov committed the cash he had just earned to buy shares in European banks. Sources report that Kerimov proposed to the banks whose shares he was buying to leverage up his stake, so that he exposed more loan money than cash to the purchase transactions. There is speculation that he was allowed to borrow half of the share acquisition price, if he put up half in cash. Several banks are reported to have been on Kerimov’s target list, including Fortis of Belgium, Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, and Royal Bank of Scotland. But if Super-Boy bought into Fortis at peak of around €140 per share in the first half of 2008, he would have faced a spiraling disaster in the second half, as the share price collapsed to €10. In fact, Fortis had to be rescued from insolvency by the Belgian, Dutch, and French governments, and sold to BNP Paribas.

As the European bank shares lost market value, their value in Kerimov’s asset portfolio dwindled, but the loan value remained the same, so the banks started issuing margin calls. In simple, Kerimov had to pay out of his cash-pocket to cover the difference between loan value he had accepted and asset value, which was plummeting. If Kerimov had also been buying Credit Suisse, the downward spiral wasn’t as severe, but the bank shares collapsed from around 55 Swiss francs when Kerimov is known to have been buying, to CHF25 at the end of 2008. If he bought into Deutsche Bank, the spiral went from €77 to €17; Morgan Stanley from $50 to $10; and Royal Bank of Scotland from 70 pence to 10p.

A version of what happened that has appeared in the Russian business press suggests that Superboy took more advantage of this collapse of bank share value than he was himself taken advantage of. Noone is saying whether the kryptonite factor was bad for everyone except Superboy.

Never mind that the bank share prices have been recovering this year, for this year is too late. The sources who report that Kerimov had applied his Russian leveraging strategy to the European banks claim that the swift loss of value imposed a heavy drain on Kerimov’s cash position by the end of 2008, and left him with limited new borrowing capacity this year, at least among the European banks.

|

Notwithstanding, back home in Superboy’s Smallville, between April and July of 2009, Kerimov paid $1.3 billion cash to buy Vladimir Potanin’s 35% share in Polyus Gold, making Kerimov the new co-controlling shareholder of Russia’s largest goldminer with Mikhail Prokhorov. The deal terms reportedly gave Kerimov a 60% discount to the market price – another Superboy feat! But the presumption that Kerimov had cash to spare, and large credit lines to draw on, cannot be verified. |

One possibility is that while he remains at the head of the buying syndicate, he may no longer hold as large a share of the asset as he and his partners maintained in their earlier Russian deals. For public shareholders of Polyus Gold, who are trying to forecast what difference Kerimov will make to the performance of the company, compared to previous owner Potanin – and also how long Kerimov will stay before selling out, as he did with Polymetal – testing this speculation makes the difference between premium and discount in the share price of the company. After two years of less than transparent shenanigans between Prokhorov and Potanin, and between executives and board members, raised the risk discount on Polyus Gold, Kerimov’s silence may not improve matters.

Moreover, even with the gold price holding above $1,000 per ounce, the most optimistic forecasts for Polyus Gold’s earnings and net income for the second half of this year do not allow a dividend payment to Kerimov of more than about $80 million from this venture for the year – and that won’t be paid until some time in the spring. So, if a recent French intelligence publication is anything to go by, Kerimov is having immediate financial problems in Switzerland and elsewhere that will readily consume that much of this cashflow, maybe more. Sources in Switzerland are reported to be claiming that in Lucerne, where Kerimov has run the headquarters of his SWIRU holding and his Millennium investment group, there are repayment claims against him from Karl Steiner, a construction company, and loan claims from Credit Suisse.

Steiner reportedly built a residential complex for Kerimov near Lake Lucerne; the financing is unclear, and is reported to have involved a mortgage by a unit of Credit Suisse. The Lakefront Center, a hotel, office and apartment complex Steiner built on the lakeside, was an earlier paid-up investment by Kerimov through a Credit Suisse asset management unit. Another office complex at Matthofstrand 8, overlooking Lake Lucerne, is registered as the office address of SWIRU. The block is also home to the Studhalter group, which has been an important business ally of Kerimov’s, at least until recently. Credit Suisse is reported to be the principal lender for Kerimov’s stakes in the building, as well as his motor-yacht, Ice, an aircraft, and other real estate assets, which reportedly extend to London assets. Ice is one of the best-known motor yachts in the world, and the sale to Kerimov by its initial Swiss owner, Ernesto Bertarelli, plus renovations and refitting, may have cost as much as $300 million. If as much of that was borrowed as is Superboy’s modus operandi, then the question is – is he keeping up payments, or keeping the assets out of range of court orders?

Credit Suisse declines to give details of its exposure to Kerimov and his companies. So too the Steiner group.

But there is one place where there is no code of silence and plenty of talk about Kerimov – all of it positive. That is the Russian republic of Dagestan, which Kerimov has represented in the Russian senate for almost two years now. The leading news source of the region, the Dagestan branch of the state RIA news agency, was asked if it has ever interviewed Kerimov. It was also asked to identify one or two things he has done that have been positive for the region.

A source at the agency said Kerimov has never granted an interview. However, the source added, the agency is “looking forward to such an occasion”. Kerimov’s reputation is “respected and appreciated in Dagestan, especially in his native city, Derbent,” the source added. The reason, she explained, is that he has arranged for his Moscow vehicle Nafta Moskva to be registered to pay taxes in the region. It was reported by the news agency in July 2008, for example, that about one rouble in every 14 in the Dagestan budget comes from Kerimov. Derbent, where Kerimov is registered as resident, is allocated for its budget 40% of the total Nafta Moskva pays to the republic. In 2007-2008, this amount was reportedly 1.5 times bigger than the rest of the city’s budget income. The city government, RIA Dagestan has reported, has “created a special programme, according to which the means from tax payments by S.Kerimov into the budget will be distributed for the priority needs of the city.”

Milestones in Superboy’s career so far!

• born March 12, 1966; grew up in Derbent, Dagestan.

• trained in judo and economics; married daughter of regional functionary of the Communist Party.

• early-1990s – works for Eltav, Dagestan enterprise, supplying transistors and semiconductors for television manufacturers.

• about 1993 — moves to Moscow to represent Eltav in Federal Industrial Bank (Fedprombank); buys out other shareholders of the bank to become controlling shareholder by 1996.

• 1994-96 – works with Magomet Tagir Abdulbasirov, a Dagestani who heads Federal Food Corporation, which drew funds from the Ministry of Agriculture budget through Fedprombank.

• 1997 — Fedprombank becomes the controlling shareholder of the Rosaviaconsortium, which in turn consolidates control of Vnukovo Airlines; a Murmansk aviation enterprise; and an airline ticketing agency. Kerimov’s partners in the Rosaviaconsortium venture were two Dagestanis, Ibragim Suleimanov and Tatevos Surinov.

• 1998 – Kerimov moved into Nafta Moskva (NM), which in turn operated as trading commissionaire for Surgutneftegaz, one of NM’s shareholders. NM was the successor of the Soviet-era petroleum trading monopoly, Soyuznefteexport. Substantial NM cash deposits were lost in the bank crisis of August 1998, and Kerimov capitalized by arranging a buyout of NM, allied with Surgutneftegaz. Kerimov specialized in share dealings involving Transneft, small oil producers, petroleum product distributors, etc., achieving substantial multiples. Funds used in the acquisition stage came from various sources.

• 1999 – bought out Surgutneftegaz’s stake in NM, and became 100% shareholder of the company.

• December 1998-March 1999 – NM negotiated with US oil company Bayoil and with the Iraqi government in Baghdad for a programme of oil shipments and trades, based on allocations granted to the Duma politician, Vladimir Zhirinovsky. During 1999 shipments of about 15 million barrels were executed under the contracts with NM, and total commissions paid totaled about $2.5 million.

• 1999 — press reports claim that NM quadrupled its rate of return on $100 million worth of Transneft preference shares.

• December 1999 – elected to the State Duma on the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia list, led by Zhirinovsky.

• 2000-2001 – NM began its own production of crude through small regional producers, such as Nafta-Ulianovsk and Ob-neftegazgeologia, but in 2001-2002 Kerimov sold these assets to Mikhail Gutseriev, who went on to create the Russneft group. Under pressure from the Prosecutor General, that was sold to Oleg Deripaska in 2007.

• 2001-2002 – NM arranged the takeover of Andrei Andreyev’s assets, including Nosta (Orsk-Khalilovsk) Steel, which had been beset by conflict between two rival shareholder factions; Avtobank; and the Ingosstrakh insurance company. The ultimate beneficiaries of this transaction turned out to be Deripaska, who took over Ingosstrakh for his Basic Element holding; and Deripaska and Alisher Usmanov, who started as co-partners for Nosta, until Usmanov bought Deripaska out. Andreyev tried unsuccessfully to litigate for recovery in the courts of Moscow and Cyprus.

• 2002 – Kerimov hires Alfa Eco executive Alexander Mosionzhik, an expert in arbitraging, and he becomes the chief executive of NM, replacing Kerimov’s former partner, Dzhabrailov Shihaliev. Mosionzhik remains CEO of NM; after the 2005 takeover of Polymetal, he became chairman of the board at Polymetal. After Kerimov sold out of Polymetal, Mosionzhik stepped down from the board.

• 2004 – NM starts buying shares of Gazprom and Sberbank. NM buys a Gazprom stake of 2.1%, while other Kerimov entities also acquire Gazprom shares; Gazprom identifies publicly the smaller of the two stakes. By 2006, Kerimov reportedly controls a 4%-4.5% stake in Gazprom and a 6% stake in Sberbank. Sberbank reportedly lends funds of at least $3.2 billion for these share acquisitions.

• 2005 – Kerimov helps to take control of the Moscow real estate and construction company, SPK. This was then resold to Deripaska. A similar transaction was carried out by Kerimov to take control of the Moscow retail mall Smolensk Passage, and then resold to the Gutseriev family.

• On May 15, 2005 the US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations published a detailed 49-page report on the involvement of Vladimir Zhirinovsky in the Iraq-UN Oil for Food programme. This is entitled: “Report on Oil Allocations granted to Vladimir Zhirinovsky”. The full text can be found at: http://hsgac.senate.gov/_files/PSIVladimirZhirinovskyReport.pdf [1] Evidence implicating NM appears in the report, pages 14-29, but there is no mention of Kerimov by name, and the amount of the alleged commissions reported is $2.5 million. No evidence is presented that these funds ended up with NM.

• Autumn 2005 – Kerimov buys Polymetal from the ICT group of Alexander Nesis. According to ICT, payment was delayed for several weeks while Kerimov raised the funds by loan from Sberbank.

• 2005-2006 – Kerimov acquires control of cable television networks in Moscow and St.Petersburg, and starts construction of a 430-hectare residential development outside Moscow.