[1]

[1]

By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with [2]

The Russian oligarchs created by the Yeltsin Administration and continued by the Putin Administration (with a handful of deductions) have never trusted Russia.

That’s why they have been willing to pay exorbitant prices for offshore assets – mines, steelmills, jet planes, motor yachts, Old Master paintings, and mansions with sea views – because the cash had been transferred out of Russia tax free, often stolen from other Russians or the state, sometimes in suitcases, concealed in chains of transfers between impenetrable holding companies, trusts and cutouts, laundered in violation of the Russian statutes on money laundering, which on Kremlin and Central Bank orders are not enforced. In other words, money that was hot and cheap.

Naturally, this lucrative cashflow has been vulnerable to raiding by individuals, especially Russians, acting on the principle that it isn’t illegal to steal from a thief and on the method that it is easy to raid when asset ownership depended on whispers and handshakes.

When these Russian robbers have fallen out, however, they have taken their disputes to the High Court of London to adjudicate. But why would such Russians trust the British courts and lawyers? Of course, they haven’t; they don’t. But they trust the Russian courts and lawyers much less.

The most famous of the High Court cases between two Russian robbers was Boris Berezovsky versus Roman Abramovich. That was decided in 2011 by the judge on her conclusion that while on the evidence testified to, the two were grand larcenists, especially from the Russian state, Abramovich was the more convincing liar of the two. Berezovsky lost, and as he faced bankruptcy, he killed himself in his London mansion full of paintings which he couldn’t sell because they were all forgeries. Altogether, the case lasted for five years, 2007-2012; Berezovsky’s losing claim totalled $5.6 billion, and more than twenty barristers were engaged for all sides, and more than that number of solicitors [3]. The legal costs of the case came to more than $100 million.

This is how it ended [4]. Then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin added his finale months before the judge: “What can I say? It would be better if they held this trial in Russia. [Question: Would Russia gain from this economically?] This would be more honest – both for them and our country. The money was made and stolen here – let them divide it here, too [5].”

Less famous, but much longer and more costly, was the group of London court cases revolving around the Russian state shipping group Sovcomflot and its associated companies which, altogether, run the largest energy tanker fleet in the world. The cases ran for sixteen years (2005-2021); were heard by thirteen judges in the High Court, the Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court; in legal fees and penalties they cost more than $200 million. Two Russian shipping executives and a Russian charterer were acquitted and compensated. They were then tried in a Moscow court; convicted on evidence the London courts had dismissed; and sentenced to long prison terms in absentia, because they had won refuge from the injustice and granted asylum in the UK.

President Putin has had nothing at all to say about the two outcomes of the case. For his reasons and the conflicting directions he has given over the years on Russian shipping policy, read the book [6].

The Russian aluminium (Rusal) oligarch Oleg Deripaska (lead image, right) has probably run more cases in the High Court and over more years than any other Russian litigant. They can be followed in this archive [7]. In one of these lawsuits decided last year, the judge opened his ruling by saying: “It is fair to say that the Claimants (“the Deripaska Parties”) and Vladimir Chernukhin and his company Navigator Equities Ltd (“Navigator”) (“the Chernukhin Parties”) are not the best of friends. It is also fair to say that the honesty and integrity of both of Mr. Deripaska and Mr. Chernukhin has from time to time been found to be wanting in cases before the English Courts, not least in previous proceedings before this court under sections 67 and 68 of the Arbitration Act 1996 [8].” — Para 1. Deripaska won his case as the judgement concluded that “the Deripaska Parties wish to discover the identity of the persons who, it is strongly arguable, forged a document designed to deceive this court and an arbitral tribunal, and to defraud them of some US$300m. I consider that the granting of the relief sought in this case is a necessary and proportionate response to this serious wrongdoing in all the circumstances.” — Para 123 [8].

The notoriety of these cases and of the litigants has advertised the availability of the British courts and lawyers to serve increasingly large numbers of corporations and individuals with big-money claims and personal axes to grind. Better and more predictable value, they calculate, to spend their money on British lawyers in London courts than on bribes and other “administrative measures” in the Russian courts.

In practice, the escalation of the British Government’s war against Russia on the Ukraine battlefield and in economic sanctions, especially against the oligarchs, ought to have stopped the lawyers from taking on new cases and the courts from hearing them. But this hasn’t happened.

The big reason is the war itself — the Russians are retaliating against the sanctions by refusing to repay British and other banks for the credits they received before they were sanctioned. The principle is the same – it isn’t illegal to steal from a thief. The foreign banks are also using the sanctions to shield themselves from the judgements of the Russian courts in paying their obligations to Russian companies.

Reviewing 257 judgments handed down by the London commercial courts between April 2024 and March 2025, Portland’s bible for the legal profession, Commercial Courts Report 2025 — published on May 19 [9] — recorded that the courts “have had a record year for litigant diversity, with ninety-three different nationalities represented – the highest ever recorded. This is the third consecutive increase year on year. Sixty-two per cent of litigants were not from the UK. This is the second highest ratio of international to domestic parties recorded since data collection began [10].”

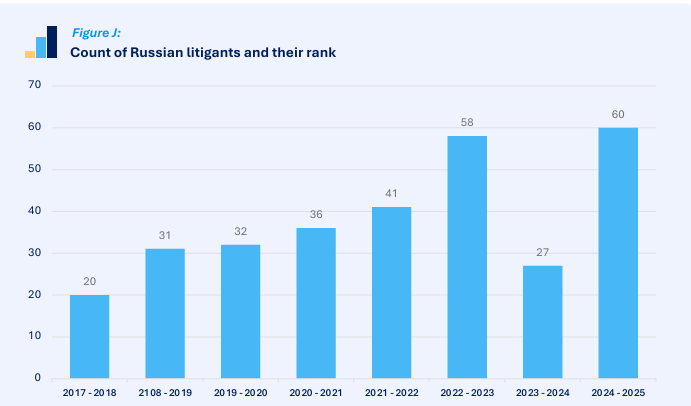

Last year also marked a return to prominence for the Russians. “Since 2018, Portland’s report has found a sustained, strong presence of Russian litigants in the Commercial Court. Last year this number dropped dramatically. But 2025 has seen a dramatic rebound, with 60 Russian litigants, the highest figure since our records began, up from 27 last year. 80% of Russian litigants had legal representation, up from just 30% in 2024. Just nine Russian parties appeared as claimants, compared to 51 as defendants, meaning that 85% of Russian litigants were on the defending side, the widest gap we’ve seen in recent years [9].”

[11]

[11]"Between 2020 and 2023, Russian litigants steadily climbed the ranks, rising from 32 cases in 2020 to a peak of 58 in 2023. For four consecutive years, Russia held firm in the top three foreign jurisdiction spots, taking 2nd place in both 2022 and 2023. It was a clear indication that, despite mounting international and legal pressure, claims involving Russian parties were continuing to make their way through the courts due to the lag time between sanctions biting and this coming through in the judgment data. That trend seemed to falter in 2024, when Russia dropped to 10th place with just 27 litigants, a more than 50% decline year-on-year. The fall likely reflected a mix of factors: ongoing sanctions, a cooling legal appetite and growing uncertainty around international enforcement. But 2025 has seen a dramatic rebound, with 60 Russian litigants, the highest figure since our records began, and a return to 3rd place." Source: https://portland-communications.com/ [12] -- page 11

“The number of Russian litigants using the Commercial Courts could well be higher when considering that Russian-owned businesses remain involved in the courts. Their owners could simply have moved their headquarters to a new jurisdiction outside of Russia.” These appear, for example, in the growing number of litigants registered in the financial havens of Cyprus, Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, and of course, the UK.

[13]

[13]Source: https://portland-communications.com/ [12] -- page 3.

In the 26-page Portland report [10], the impact of the war in the Ukraine was noted as causing a severe downturn in London court litigation by Russians in between 2022 and 2024, but then a revival last year. There was “a fall of over 50% year-on-year from 22/23 to 23/24. The number has, however, rebounded significantly this year, recovering all lost ground and then some, even though the geopolitical and sanctions landscape has not really thawed. It is likely that there are several factors underpinning this return to form. Perhaps most importantly, it has clearly become easier for Russian litigants to access legal representation in the UK (even where sanctioned – which many of the 60 referred to in this publication are). This is borne out by the analysis in this report revealing that 80% of Russian litigants this year had legal representation, compared to just 30% the year before.”

The main driver of this wartime growth of legal business has been the British Government’s sanctions war itself. On the one hand, one form which Russian defence and fightback have taken is to refuse to pay contract charges, loans, and other obligations to British and European banks and business intermediaries because the sanctions regime has blocked the payment system. For their defence, the foreign banks have disputed the jurisdiction of the Russian courts and sued in the High Court to keep jurisdiction in the UK and block the Russian courts from ruling in favour of the locals.

Prominent examples are the litigation, first in Moscow, then in London, between Barclays Bank and Russian state bank VEB for recovery of $147 million in currency swaps; between Barclays and the Russian commercial bank, Sovcombank; and between RusChemAlliance (RCA) and Commerzbank, Unicredit and Deutsche Bank for payment of several hundred million euros in performance bonds for LNG plant construction contracts worth €10 billion; €2 billion had been paid up front by RCA before the sanctions war stopped the projects. The court papers of these cases also reveal the foreign banks are using the sanctions war to avoid meeting their payment obligations to the Russians.

“The recent trend is the sheer number of high-value commercial disputes arising out of the Russian sanctions themselves, for example where one party claims performance of a contract is prohibited by sanctions. While not solely the preserve of Russian parties, such disputes are naturally more likely to arise where one party is Russian and even more so where that party is designated. Equally, while the effects on a commercial transaction of sanctions can cut both ways, one explanation for the disproportionately large number of the Russian litigants in the London Commercial Court this year defending claims (51 of the 60 litigants) may be a trend of default by Russian parties who have been designated or who are otherwise impeded in carrying out their contractual duties by sanctions which are ultimately designed to have a greater impact upon them [14].”

The UK Treasury, which directs the sanctions war against Russia, has also made it more profitable for British lawyers to run Russian litigation by raising the initial fee cap of £500,000 which lawyers could bill sanctioned Russian clients to £2 million, thereby “permitting”, according to Portland [14], “more heavy-weight commercial disputes to be properly [sic] litigated.”

For Private Eye — now a nose ahead of The Economist as the most widely read London news magazine — this is nothing short of war profiteering by traitorous Englishmen in the service of criminal Russians. The principal Private Eye reporters on business are Michael Gillard father and son, who write under the singular nom de plume “Slicker”. The Gillards and Ian Hislop, editor of Private Eye, are Russia-haters applauding the Ukraine war.

In the magazine’s issue of June 27-July 10 [15] (No. 1652), they reported data obtained by a freedom of information request to the Treasury Office of Financial Sanctions: these show the total paid to UK lawyers to represent sanctioned Russians between October 2022 to April of this year came to £62 million. But in the most recent six months to April, the total reached a record high of £18.95 million; the previous record had been £13.94 million between April and October 2024. The new record came from 46 law firms filing 280 applications for a sanctions relief licence to cover their Russian client fees.

Summing up the Portland report, the Gillards declared: “Lawfare continues to rage in the courts, generating multi-millions for London’s legal finest from representing sanctioned Russian individuals and companies involved in commercial spats over money while the real war in Ukraine grinds on, costing more lives…The irony is that often no judgement or damages award can be effected. If it is against a sanctioned Russian litigant, the courts in Russia are likely to refuse to enforce it, as this is Kremlin policy.”

Omitted from the Gillard judgement is the evidence in the London cases that the British judges favour their own jurisdiction to support the sanctions war and block multi-million dollar, euro and pound payments to the Russian claimants. Private Eye’s intrepid investigators have missed that the increased relief allowance the British Government has provided the London lawyers has subsidized the vaster sums which the courts have ruled should not be returned to Russia.

PORTLAND REPORT — TABLE OF RUSSIAN CASES IN LONDON COURTS, 2024

Judgments with Russian Litigants

__________________________________________________________________

| Magomedov & Ors v TPG Group Holdings (SBS) LP & Ors [2025] EWHC 304 (Comm) (14 February 2025) https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/CL-2023-000401-Final-Judgment-17-01-25-1.pdf [16] |

| Magomedov & Ors v TPG Group Holdings (SBS) LP & Ors (Rev1) [2025] EWHC 59 (Comm) (17 January 2025) https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/CL-2023-000401-Final-Judgment-17-01-25-1.pdf [16] |

| Google LLC & Anor v NAO Tsargrad Media & Ors [2025] EWHC 94 (Comm) (22 January 2025) https://jusmundi.com/en/document/decision/en-google-llc-and-google-ireland-limited-v-ano-tv-novosti-nao-tsargrad-media-and-no-fond-pravoslavnogo-televideniya-judgment-of-the-high-court-of-justice-of-england-and-wales-2025-ewhc-94-tuesday-7th-january-2025 [17] |

| Renaissance Securities (Cyprus) Ltd, Re [2024] EWHC 2843 (Comm) (06 November 2024) https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2024/2843.html&query=(Chlodwig) [18] |

| Barclays Bank PLC v VEB.RF [2024] EWHC 3088 (Comm) (28 November 2024) https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2024/3088.html [19] |

| Barclays Bank Plc v VEB.RF [2024] EWHC 2981 (Comm) (19 November 2024) |

| Magomedov & Ors v Kuzovkov & Ors [2024] EWHC 2527 (Comm) (04 October 2024) |

| Filatona Trading Ltd [Oleg Deripaska] & Anor v Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan UK LLP [2024] EWHC 2573 (Comm) (14 October 2024) |

| Filatona Trading Ltd & Anor v Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan UK LLP [2024] EWHC 2751 (Comm) (30 October 2024) |

| https://caselaw.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ewhc/comm/2024/2573 [8] Renaissance Securities (Cyprus) Ltd v ILLC Chlodwig Enterprises & Ors [2024] EWHC 2460 https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2024/2460.html [20] |

| Gorbachev v Guriev [2024] EWHC 2174 (Comm) https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Gorbachev-v-Guriev-final-for-handdown.pdf [21] |

| Google LLC & Anor v Nao Tsargrad Media [2024] EWHC 2212 (Comm) (19 August 2024) https://www.casemine.com/judgement/uk/6791397028730f3ea8e47e86 [22] |

| Bayerische Landesbank & Anor v Ruschemalliance LLC [2024] EWHC 1822 (Comm) (28 June 2024) https://jusmundi.com/en/document/decision/en-landesbank-baden-wurttemberg-v-ruschemalliance-llc-judgment-of-the-high-court-of-justice-of-england-and-wales-2024-ewhc-1822-friday-28th-june-2024#decision_66678 [23] |

| Magomedov & Ors v PJSC Transneft & Ors [2024] EWHC 1176 (Comm) (21 May 2024) |

| LLC EuroChem North-West 2 v Societe Generale SA & Ors [2024] EWHC 1084 (Comm) (08 May 2024) https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/EuroChem-v-Societe-Generale-and-other-08.05.24.pdf [24] |

| Commerzbank AG v Ruschemalliance LLC [2024] EWHC 1474 (Comm) (13 May 2024) https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2024/64.html [24] |

| Barclays Bank PLC v VEB.RF [2024] EWHC 1074 (Comm) (10 May 2024) |

| Barclays Bank PLC v PJSC Sovcombank & Anor [2024] EWHC 1338 (Comm) (24 May 2024) https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2024/1338.html [25] __________________________________________________________________________ |

Cases with Russian Litigants

_________________________________________________________________

| Magomedov & Ors v TPG Group Holdings (SBS) LP & Ors |

| Google LLC & Anor v NAO Tsargrad Media & Ors |

| Barclays Bank PLC v VEB.RF |

| Magomedov & Ors v Kuzovkov & Ors |

| Filatona Trading Ltd [Oleg Deripaska] & Anor v Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan UK LLP |

| Renaissance Securities (Cyprus) Ltd v ILLC Chlodwig Enterprises & Ors |

| Gorbachev v Guriev |

| Bayerische Landesbank & Anor v Ruschemalliance LLC |

| Magomedov & Ors v PJSC Transneft & Ors |

| LLC EuroChem North-West 2 v Societe Generale SA & Ors |

| Commerzbank AG v Ruschemalliance LLC |

| Barclays Bank PLC v PJSC Sovcombank & Anor |

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Portland, Simon Pugh