By John Helmer, Moscow

Coca-Cola, the world’s largest beverage company, is having trouble swallowing in Russia. That’s to say, increasing numbers of Russian consumers have stopped drinking Coca-Cola, as well as the company’s other carbonated drinks and juices, forcing the closure of a half-billion dollars in beverage plant investment – and the concealment in US stock exchange reports of just how bad the situation is.

The bad news for Coke got significantly worse, according to company reports last week, when it was admitted that volume and value of sales in Russia fell in the September quarter by “low single digits”. In the press release version, the November 6 report claimed the problem was “macroeconomic slowdown in Russia”.

In the fine print, Coke admits the problem is that Russian consumers are reacting negatively to the American brand because of the US sanctions war and the conflict in Ukraine. “Volume in Russia declined by low single digits in the third quarter, following a low single-digit increase in the comparable prior-year period. Volume for the first nine months declined by just under 1%. The escalation of the geopolitical developments continued to adversely impact the economy and the consumer sentiment in the country. At the same time, disposable income was under further pressure by the currency depreciation and sanctions driven inflation in the food and beverage categories. As such, volume decline in the quarter was broad-based, with all major categories except Juice posting lower volume. Trademark Coca-Cola declined by 4% and Sparkling by 7%, with only Fanta recording substantial growth, supported by the launch of new flavours.”

For beverages produced by Coca-Cola in Russia but sold under local brand-names, the market result in the quarter was different. “Volume in the juice category grew by double-digits in the quarter, supported by the inclusion of the Moya Semya brand, while both our mainstream brand Dobry and our premium brand Rich grew by high single digits. As a result, we expanded our value share in Juice.”

A statement in the risks section of the latest financial report concedes that if the war gets worse, the future for Coke is parched. “The ongoing situation in Ukraine and the Russian Federation, and any further economic sanctions that may be imposed on the Russian Federation by the US and the European Union, could adversely affect the Group’s operational and financial performance. We are continuously monitoring developments in that region.”

Coca-Cola, headquartered in Atlanta, and listed on the New York Stock Exchange, has operated in Russia directly, and also through Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company (HBC), which is separately listed on the Athens and London stock exchanges. The main company has a current market capitalization of $186 billion, and its share has moved upwards over the past year by 13%. HBC’s current market cap is £5 billion ($8 billion), but it has fallen 30% in the same period.

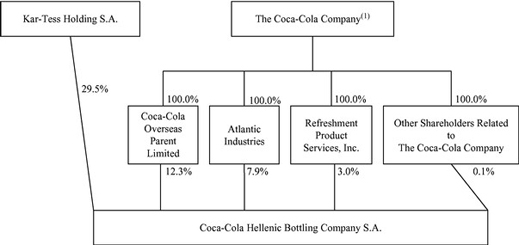

HBC is a Cypriot-owned company, not an American one, because Kar-Tess, a Luxembourg entity, holds more shares in HBC than Coca-Cola US. Kar-Tess is itself owned by several entities, including another Luxembourg front called Boval S.A. The controlling stakeholder is the Leventis family, which started in Cyprus and holds multiple passports. This is how the shareholding looked in 2011, when the Leventis family held 29.5% and Coca-Cola US, 23.3%.

Current reports from the main company indicate that the Leventis family owns 23.3% of HBC, while the US concern owns a fraction less — 23.2%. Inside the international Coca-Cola group, HBC says it is second in sales volume and revenue to the domestic US bottler.

In Zug HBC is run by a Greek, Dimitris Lois (below left). The Russian business, which also runs its revenues through Zug, is headed by Stefanos Vafeidis, also Greek (below right, 1st right).

According to HBC, total sales for the third quarter and for the nine months to September 30 decreased by 4.8% and 3.9%, respectively, to 547.6 million and 1.5 billion unit cases; each case counts 5.7 litres. Total sales revenue for the company for the nine months to September 30 dropped 5.6% to $5 billion.

Russia is accounted by the company in what it calls its emerging market group; this includes Nigeria and several smaller markets like Belarus, Romania and Ukraine. Russia sales data are masked by the other countries in the regular financial reports; the data appear when HBC wants to release them – and that isn’t now. In Russia HBC manufactures and distributes the Coca-Cola brand, Coca-Cola Light, Sprite, Fanta, BonAqua (water), Nestea, Powerade, Burn and Gladiator, Schweppes tonic, Krushka i Bochka kvass, and juices and nectars with the brand names Fruktime, Rich, Dobriy, and Pulpy. This year the production volume of the company in Russia is 12.5 million liters per day.

Russian reports suggest that about one-quarter of Coca-Cola’s shipment volume and sales comes from juice, while the Coca-Cola brand and the other carbonated drinks make between 50% and 60% of the Russian business. The company hints that there is little prospect that even robust growth for the juice lines can offset declines for Coca-Cola and the associated carbonated brands.

A legislative proposal by the Communist Party faction in the State Duma to impose a tax on sugar content would, if enacted, make the drink too expensive, and put the kybosh on Coke. The sponsors of the legislation say their target is obesity and other health risks associated with Coca Cola’s best known drinks. A party source says the bill has yet to be submitted to the Duma because of media criticism and lobbying. Details of the bill are still being discussed in the party, he said.

This isn’t a unique Russian initiative. In California this year, a majority of San Francisco city voters supported adding a 24-cent tax to sugar-heavy soda drinks, but the measure failed to reach the super-majority required.

Last week, the city of Berkeley carried a 12-cent tax by 75%. Similar measures have been attempted across the US, but have been blocked by local courts or industry lobbying. Other countries to attempt sugar and soda taxes to deter young drinkers include Mexico, France, and India.

Source: http://www.berkeleyvsbigsoda.com/

Coca Cola concedes in company papers this year that it is facing the risk of public perception that “consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, including those sweetened with HFCS or other nutritive sweeteners, is a primary cause of increased obesity rates and are encouraging consumers to reduce or eliminate consumption of such products.” As a result, the corporation acknowledges the risk to its worldwide sales and profits from “possible new or increased taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages by government entities to reduce consumption or to raise revenue.”

Three years ago, almost to the day, a start to the decline of Coca Cola in Russia was reported; at the time that was not because of the sugar content, but because of the fizz. Read that story here. The reasons for this Russian development were Coke’s high price and the fickle taste of young Russian consumers. The conclusion then was: after the novelty wears off, Russians don’t like Coke much. In this respect, their palates are almost unique in the civilized soft-drinking world. And so, for Coca-Cola to continue showing profits in the Russian market, the company has concluded that it must buy up Russian juice companies, and sell something different from Coca-Cola.

In the interval, Vadim Drobiz (right), a leading expert on the Russian alcohol beverage market, believes there are common factors at work in the alcohol and non-alcohol beverage markets, which are causing Coca-Cola’s decline. “These beverages are very expensive in Russia. The main consumer is youth, and they are becoming fewer every year. This problem of demographic decline has been observed since 2008. Another reason for decline is the reduction in the purchasing power of the young.”

In the interval, Vadim Drobiz (right), a leading expert on the Russian alcohol beverage market, believes there are common factors at work in the alcohol and non-alcohol beverage markets, which are causing Coca-Cola’s decline. “These beverages are very expensive in Russia. The main consumer is youth, and they are becoming fewer every year. This problem of demographic decline has been observed since 2008. Another reason for decline is the reduction in the purchasing power of the young.”

“Also, I do not exclude that due to the association of the brand with America that is a possible cause of the decline, too.”

These days Moscow’s investment banks have fewer analysts specializing on the consumer market; those who do, focus on the listed supermarkets, not on the products moving on and off their shelves. According to Maxim Kalyagin of Finam, Russian consumers are opting against Coca-Cola because they are choosing “healthier drinks – juice and water. This is a general trend towards a healthy lifestyle. The second reason is the deterioration of the economic situation, the reduction of consumer ability [to spend]. To argue that this is due to the American brand requires comprehensive research. Right now it looks speculative.”

Coca Cola’s investors may be surprised at the bad news, but that’s because in the US the company does its best to keep the Russian developments out of its annual reports. Its 10-F filing to the US Securities & Exchange Commission for 2013 – issued on February 27, 2014 — reports “exceptional capabilities in the marketplace, integrated marketing campaigns and greater consumer choice in package and price options. Growth in still beverages was led by packaged water, juices and juice drinks, and teas. Russia reported unit case growth of 3 percent, driven by growth of 11 percent in brand Coca-Cola. Still beverage growth in Russia included growth of 7 percent and 24 percent in our juice brands Dobriy and Rich, respectively. Unit case growth in Russia was favorably impacted by the Company’s marketing activities related to the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics and Olympic Torch Relay.”

Weeks later the collapse of the Nidan line of juice products and production plants was well-known in Moscow. But in the US company’s audited financial reports, the brand-name Nidan is missing from the record of impairments, write-downs, and losses. The word Nidan does not appear at all in the auditor’s notes.

Instead, there is this footnote for the third quarter results: “operating income (loss) and income (loss) before income taxes were reduced by $7 million for Bottling Investments as a result of the restructuring and transition of the Company’s Russian juice operations to an existing joint venture with an unconsolidated bottling partner.” The term “operations” is disguise for Nidan; the “unconsolidated bottling partner” is HBC. The footnote for the nine-month period even tries camouflaging the term, loss: “operating income (loss) and income (loss) before income taxes were reduced by $32 million for Bottling Investments as a result of the restructuring and transition of the Company’s Russian juice operations [Nidan] to an existing joint venture with an unconsolidated bottling partner [HBC]”.

A third footnote says the quarterly loss from the collapse was $5 million; the nine-month loss, $30 million.

Lossmaking isn’t new in Nidan’s history. When Coca-Cola US bought the company in August 2010, its cash outlay was $276 million, and it took on about $150 million in Nidan debt. For the three years preceding, Nidan had recorded a decline in juice sales from $270 million to $180 million. For more, read this.

By June of this year, Nidan’s share of the Russian juice beverage market had dropped from 11% to 6.6%. According to a detailed study by Juliana Petrova, published this August, the US management of Coca-Cola spent heavily on new packaging, juice flavours, marketing agents, price discount and bonus agreements with supermarkets, and fresh advertising pitches — to little avail. Shipments grew modestly, as did sales revenues. But costs leapt. So much so that by last year, Coca-Cola decided to abandon television advertising altogether and sacked the Nidan marketing team.

At the start of this year, the Nidan juice plants were operating at one-third of their capacity. In June the US company decided to close down entirely, and turn its juice operations over to the Multon plants which HBC had bought in 2005 for $500 million. The two companies had operated separately in the Russian juice market in order to not to violate the dominant market share threshold of the Federal Antimonopoly Service. When Coca-Cola reports refer to the successful growth of its Russian juice lines, it is referring to Multon, not Nidan. Counting the purchase price, debt, fresh investment, and operating losses, Nidan has cost Coca Cola more than $500 million.

Moscow spokesmen for Coca-Cola and HBC were asked to clarify the downward trend for the brand-name. According to Vladimir Kravtsov of Coca-Cola, he cannot say more than was said in the reports of the main Coca-Cola company. As for the impact on Coca-Cola if the Duma sugar and soda tax is enacted, Kravtsov said “We don’t estimate it. In principle, such a kind of bill does not exist.”

Leave a Reply