By John Helmer, Moscow

Georhii Rudko, the chairman of the Ukrainian State Commission for Natural Resources, had nothing to do with the choice of the old British War Office as the venue; nor the timing of his speech, one day before the President of Ukraine and the constitutional order of the country were toppled. But Rudko’s presentation on the future for the oil and gas resources of Ukraine was anything but a sideshow.

Rudko was scheduled to speak at a meeting entitled “Black Sea & Caspian 2014 Conference – Unlocking Full Potential”. The date was February 20. The address was 89 Pall Mall, where the War Office was located between 1858 and 1906, just missing the Crimean War (1853-56), but managing the second Opium War against China; the three Basotho wars in southern Africa; several rebellions in India; and the Boer War in South Africa. As war offices go, the score was a grand slam for the British.

Rudko wasn’t so fortunate. The fighting in the streets of Kiev, he telephoned London to say, made it impossible for him to deliver a new version of the material he had presented to the conference the year before. According to that presentation, the western regions of Ukraine can contribute little to the future energy supply of the country and aren’t worth fresh investment. That, he said, is because the area is already “ the most long-exploited in Ukraine and the smallest by potential resources and reserves.” In the eastern regions, by contrast, Rudko said considerable reserves of oil and gas remain to be developed if there is fresh money. The area “is the largest in Ukraine by potential resources and reserves. It has 205 fields, 121 of them are being developed (gas – 64, gas condensate – 72, oil – 53). The degree of the initial potential resources realization – 57%.”

Source: Rudko presentation, page 14. This was originally given by Rudko in London at a conference arranged by the same organizer, Capital Europe Conferences, on February 14, 2013.

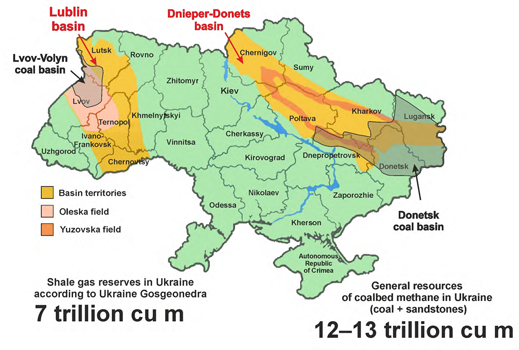

Both west and east have potential value for unconventional gas production; that’s shale or coal-bed methane gas released by hydraulic fracturing and other methods. The estimated resource was plotted by Rudko on the map like this:

Source: Rudko presentation, page 23

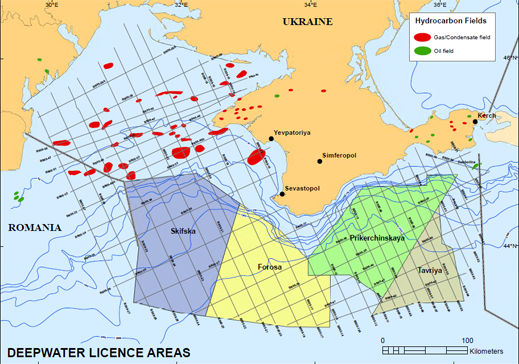

But the time required for development, Rudko conceded, is long, the cost high, and the outcome much more uncertain than his recommendation. That is for oil and gas drillers and foreign investors to concentrate on what he calls the “Southern Oil and Gas Region”. On Rudko’s map, the region’s energy riches have already been plotted in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. They lie to the north of Kerch; west of Simferopol; and south of Sevastopol. In short, they lie on the seabed within 200 nautical miles of the Crimean shore line.

Source: Rudko presentation, page 17

Until now, that is part of the exclusive economic zone of Ukraine, according to the international Law of the Sea. But if Crimea formally votes on March 16 to give up its autonomous republic status in Ukraine and join the Russian Federation, and if the Russian parliament and President Vladimir Putin formally accept, these resources are no longer Ukrainian. They become Russian.

The potential, Rudko has concluded, is enormous. The Crimean offshore areas already identified, he said, represent “a third of the undiscovered natural gas resources [of Ukraine] and a fifth of the undiscovered oil resources…including: oil and condensate – 1148 million tons and gas – 3831 billion m3. The development degree of resource potential of the shelf – up to 5%. The most prospective for the search of significant deposits is the deep part of the Black Sea. Its potential recoverable resources reach more than 1000 million tons of coal equivalent (54% of the total Black Sea resources).”

On this map, prepared by Ukraine’s state gas company NaftoGaz, there are four deepwater licence areas south and south of Crimea, which have already been delineated by Rudko’s natural resources commission. Since 2006 all four – Skifska, Foroska, Prykerchinska, and Tavriya (to use their Ukrainian names) — have been formally offered for bidding by interested investors and oil and gas explorers.

Source: NaftoGaz of Ukraine

Despite earnest efforts by several governments in Kiev, including the recent Energy Minister, Eduard Stavitsky (December 2012-February 2014), there has been no bidding interest for Foroska or Tavriya.

On January 30 Stavitsky (right) announced that the government would be trying again soon. “‘There will be contests on two areas of the Black Sea – Foros and Tavriya. We are in talks with major investors to develop the shallow shelf,’ he added.” Stavitsky has been ousted from his ministry and replaced by Yury Prodan who held the energy portfolio from 2007 to 2010. Stavitsky is not the sanctions list issued by the European Union on March 5.

On January 30 Stavitsky (right) announced that the government would be trying again soon. “‘There will be contests on two areas of the Black Sea – Foros and Tavriya. We are in talks with major investors to develop the shallow shelf,’ he added.” Stavitsky has been ousted from his ministry and replaced by Yury Prodan who held the energy portfolio from 2007 to 2010. Stavitsky is not the sanctions list issued by the European Union on March 5.

The most important of the four Crimean offshore blocks is Skifska. When Stavitsky announced a tender for the Skifska field, it was reported to hold 200 to 250 billion cubic metres of gas reserves, with an annual production estimate of five billion cubic metres a year. The field starts about 50 kilometres southwest of Sevastopol, and runs up to the Romanian sea border. There it adjoins the Romanian Neptun Deep block, in which ExxonMobil has a 50% working interest. In early 2012, Exxon announced that at a well called Domino-1, about 170 kilometres from the Romanian coast, it had “encountered gas”, according to Exxon’s 2012 Financial and Operating Review, issued at the start of 2013. “Appraisal activities are progressing with additional drilling anticipated to commence in 2013.”

According to ExxonMobil and Ukrainian government announcements, between June and August of 2012, bids for Skifska were collected and assessed. LUKoil of Russia competed against a consortium of ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, OMV Petrom of Romania, and the Ukrainian state-owned entity, Nadra Ukrainy. The Russian bid was rejected, and ExxonMobil (with a 40% operating stake) was the winner.

The ExxonMobil reports have said no more than “we are working with our co-venturers and the Ukrainian government to finalize the Production Sharing Agreement. But almost two years later, no agreement has been signed. A source close to the company says the promised payment for Skifska, a signing bonus of $325 million, won’t be paid until there is a production sharing agreement. The reason that hasn’t been signed is that Exxon and the Ukrainian government have so far been unable to agree on production, investment, tax and royalty terms. The negotiations have continued over the past twelve months, but no money has been spent drilling at sea. The only data available to Exxon so far were provided by Stavitsky and Rudko during the bidding process.

Officially, according to an Exxon spokesman, “we remain interested in the block.”

Unofficially, Exxon has halted its negotiations with the Ukrainians “due to the political situation, but is pressing ahead with several Russian projects, including in Russian waters close to the Crimean Peninsula.” This was told to New York analysts last week, and reported in Dallas on March 5. According to the report, ExxonMobil senior vice president Andy Swiger conceded the company has bigger fish to fry in the Russian Arctic than off the Crimean shore. According to Swiger, the Crimean block “has active oil seeps and that drilling would begin in 2015.” According to ExxonMobil chairman and chief executive, Rex Tillerson: “In terms of our view of country risk, geopolitical risk, other than things like sanctions, we don’t see any new challenges out of the current situation [in Russia].”

The second of the Crimean offshore blocks to have been awarded for development is next to Skifska to the east and known as Prykerchinska (Prikerchinskaya in Russian). At the time the block was put up for bidding it was estimated to hold more than 1 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The Ukrainian government award was made in April 2006, when the president was Victor Yushchenko. The winner, a junior oil explorer from Texas named Gene Van Dyke, defeated ExxonMobil, Shell, a Turkish company, and another Texan junior, the Hunt Oil Company. Van Dyke’s geography places the Prykerchinska block “in the Kerch area”, on the northeast of the peninsula.

Vanco, Van Dyke’s company at the time, claimed that Prykerchenska was “the country’s first deepwater license opportunity… The event made Vanco the first company to be awarded a Production Sharing Agreement by Ukraine for its portion of the Black Sea.” Only the production sharing agreement, which was signed in October 2007, was reversed and then subject to an arbitration proceeding in Stockholm in 2010. According to Vanco’s version, it was not until after Victor Yanukovich became president in 2011 that the government in Kiev agreed to reinstate the Prykerchenska licence and production sharing agreement. The original terms of Van Dyke’s deal provided for Vanco to pay all field development costs and then receive 80% of all production income until costs will have been recovered. From then on the split in income would be 60% for Vanco, 40% for the Ukrainian government.

It isn’t known whether the terms settled with Yanukovich in 2012 were the same. Nor have Vanco and Van Dyke responded to requests for clarification of the project at the moment. Van Dyke says on his company website that in 2010 he sold “a controlling interest in Vanco Exploration to Lukoil, retaining a substantial interest. Van Dyke Energy Company maintains that interest through PanAtlantic Energy Group.” He then appears to have restricted his direct exploration ventures to “the North Sea with a focus onshore and offshore The Netherlands.”

LUKoil’s version of the Vanco takeover refers to drilling operations in West Africa, including Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. Ukrainian press reports suggest that the price for Vanco’s reinstatement at Prykerchenska was the sale of a large stake in Vanco Ukraine to DTEK, the energy company owned by Ukrainian oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov. DTEK has acknowledged that it and two associated companies, also Akhmetov properties, “act as financial partners of Vanco Prykerchenska Ltd. in the project, which is in line with DTEK’s long-term development strategy and important for Ukraine’s energy security”. Last July DTEK’s chief executive, Maxim Timchenko, acknowledged that “in addition to energy generating companies and mines, DTEK owns a shareholding in Vanco Ukraine.” He didn’t say who remained as shareholders of the project, and DTEK has so far reported no expenditure on the block.

The public record also reveals that Van Dyke’s partner in the original 2006 bidding for Prykerchenska, as well as source of capital for the project, was Nathaniel Rothschild (lead image). In Van Dyke’s version, this came about because “Vanco had a representative in Kiev who is a former executive of BP and who had contacts with the London branch of the Rothschild family — JNR Eastern Investments Limited — which came on board as a 50-50 partner with Vanco.”

Rothschild was asked to clarify whether he still holds his stake in Prykerchenska; whether he thinks his stake has been adversely impacted by the changes now under way in the Crimean republic, and what he has done about that. Rothschild’s spokesman said he no longer occupies the post, and referred to Rothschild’s investment management office in Jersey. There it was agreed that the questions would be relayed to Rothschild for his reply. He didn’t.

Lukoil’s operating and financial reports mention only refinery assets in Ukraine; there is no reference to exploration of Crimean waters, and no report of the losing bid for Skifska or the Vanco link to Prykerchenska. For the time being Lukoil sources are considering the question of whether they might still be interested in these blocks. They are not answering.

Leave a Reply