By John Helmer, Moscow

By the European standard of destructiveness in war — civil war and invasion — only one country exceeds Russia in the frequency of violence over the past two centuries and in casualties per head of population: this is Greece. In Europe of today, no country has been as damaged by the serial attacks of the Turks, Germans, British, Americans, and also by the Greeks themselves, as Greece. No European suffers today from more impoverished future prospects than the Greek.

This is the dismal lesson of a new history, just published by a British academic and philhellene, as foreign lovers of Greece have been called since Lord Byron and Victor Hugo. The history is also a valuable record of the dozens of times Greeks appealed for Russian aid, and when Russians, having promised to help, turned out to be double-crossers. Indeed, starting from Catherine II in 1770 until Vladimir Putin today, this mistake Greeks (including Cypriots) and Russians make towards each other has been repeated. Re-reading the history may help stop the vicious cycle. So may the extended range of Russian air and sea missiles.

Roderick Beaton titles his history “Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation”.

Roderick Beaton, with the Acropolis in the background.

By modern, Beaton means starting from the turn of the 18th to the 19th centuries. He ought to have stopped at the end of the last Greek civil war – the one paid for, armed and directed by the US between 1946 and 1949 — when the number of sources Beaton could and should have listened to far exceeds the official archives, academic works and journalism on which his book depends. But that’s for Greeks to argue about, as they do.

Beaton’s story of Russians and Greeks begins in 1770 when the Empress Catherine the Great, ruling between 1762 and 1796, sent the fleet under Count Alexei Orlov into the victorious Battle of Chesme, destroying the Ottoman navy between the island of Chios and the mainland dominated by Izmir. Leading up to that, Orlov had sent Greek-Russian agents to the Peloponnese and Crete, promising naval protection, arms and infantry support for Greek rebels; the latter also wanted to expand their trade and shipping operations.

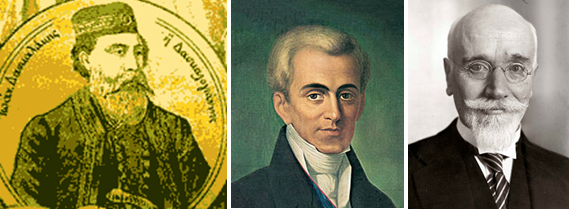

Orlov’s failure to support Daskalogiannis’s revolt in western Crete led to his heroic last stand in 1771 – and to the Russian name in Greek for this betrayal: Ορλωφικά (“Orlovika”). Beaton retells the story of the 1821 rebellion of Alexandros and Dimitrios Ypsilanti, both of them serving officers in the Russian Army, who were rejected by Tsar Alexander II. Then later in the same decade, there was the “sphere of influence” scheme proposed by Alexandros Mavrokordatos to play the British off against the Russians, while removing the Turks. In parallel, there was the rise of the Russian party of Theodoros Kolokotronis, and the election in 1827 of Ioannis Kapodistrias as the head of state. With Russian patronage when Corfu was under their control, Kapodistrias started as a Russian diplomat in the negotiations with the Austrians and British in the division of Europe after Napoleon’s defeat, rising to the post of the tsar’s joint foreign minister.

Left to right: Daskalogiannis (Ionannis Vlachos, 1730-71); Ioannis Kapodistrias (1776-1831); Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936).

As one of the three guarantor powers (the others were France and Britain) for independent Greece, Russia’s strategy, according to Beaton, was to employ the Greeks as spoilers on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire. “The fate of Greece was only incidental”, Beaton concludes. The strategic priorities for Russia were much closer: Crimea, the Caucasus, the western and eastern littoral territories of the Black Sea.

These priorities were reinforced between the Russian loss to the British and French in Crimea between 1853 and 1856 and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877, when the Russian victory placed the independence of the Slavs of the Balkans ahead of Orthodox Christian co-religionists, the Greeks. Beaton’s history of the infighting between Greeks during World War I and the subsequent failure of Britain and France to protect the Greeks of Anatolia and Smyrna from the Turkish genocide – also the story of the rise and fall of Eleftherios Venizelos; the fall and rise of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk — documents the shift in Russian state policy “from supporting the Orthodox populations of Eastern Europe in favour of those that shared a Slavic language. In this way, pan-Slavism was born. At the same time, and for much the same reason, the influential strand in Greek public opinion and political life that had maintained a ‘Russian party’…quickly tailed off. Russia was now supporting Greece’s rivals.”

Beaton mentions the domestic sources of support for the rise of the Greek Communist Party (Greek acronym KKE); he concludes that even with nominal support from the Comintern in Moscow, the KKE was “a largely imaginary threat invented in 1936 to excuse the seizure of power” by the army general, Ioannis Metaxas. In the short term Metaxas was able to destroy the KKE, “but the rhetoric of that threat would go on to nourish the creature it was meant to destroy. Communism was not a significant force in Greece in 1936. Ten years later, it would have become one…Modern notions of left and right entered Greek politics with the imposition of a manifestly and extreme right-wing dictatorship in 1936.”

Beaton appears not to be familiar with the Greek assessments of Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin, both before the Russian Revolution of 1917 and after. In May 1917 Lenin had dismissed Venizelos as “in the service of British capital”. He also dismissed the rivalry between Venizelos and King Constantine I as “laughable”. He interpreted the landing (at Venizelos’s invitation) of British and French troops from Souda Bay in the south to Thessaloniki in the north, and fighting between Greek forces which forced the king’s abdication in 1917, as reflecting nothing but the imperial ambitions of the European powers. “What kind of pressure it was and is,” Lenin wrote in Pravda, “everyone knows: pressed by hunger, Greece was blockaded by military vessels of the Anglo-French and Russian imperialists, Greece was left without bread. The ‘pressure’ on Greece was of the same order as was used recently in Russia… the dark peasants in a semi-wild corner of Russia starving to death are ‘criminals’. The imperialists of England, France, Russia are ‘civilized’; they have starved the whole country, the whole nation, to pressure to get her to change policy. Here it is – the reality of imperialist war.”

Stalin, writing in November 1920, viewed the post-war independence of Turkey, and the destruction of the Greek and Armenian communities, as bound to lead to an alliance between Turkey, Britain and France against the Soviet Union, with further pressure to grow in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and on the Russian Caucasus. “The defeat of Armenia by the Kemalists under the absolute ‘neutrality’ of the Entente, rumours of Turkey’s supposed return of Thrace and Smyrna, rumours of negotiations between the Kemalists and the Sultan, an agent of the Entente, and of the supposed cleansing of Constantinople, finally, the lull on the Western front of Turkey – all these are symptoms that speak of the serious flirtation of the Entente with the Kemalists and about some, perhaps, shift of the Kemalists ‘ position to the right. It is difficult to say how the Entente’s flirtation will end and how far the Kemalists will go in their movement to the right. But one thing is certain, that the struggle for the liberation of the colonies, begun a few years ago, will intensify, in spite of everything; that Russia, as a recognized standard-bearer of this struggle, will support by all means and by all means the supporters of this struggle, and that this struggle will lead to victory together with the Kemalists, if they do not change the cause of the liberation of the oppressed peoples, or contrary to the Kemalists, if they find themselves in the camp of the Entente.”

This ambiguity of Russian strategy towards Ankara, combined with dismissiveness towards Athens, continues today.

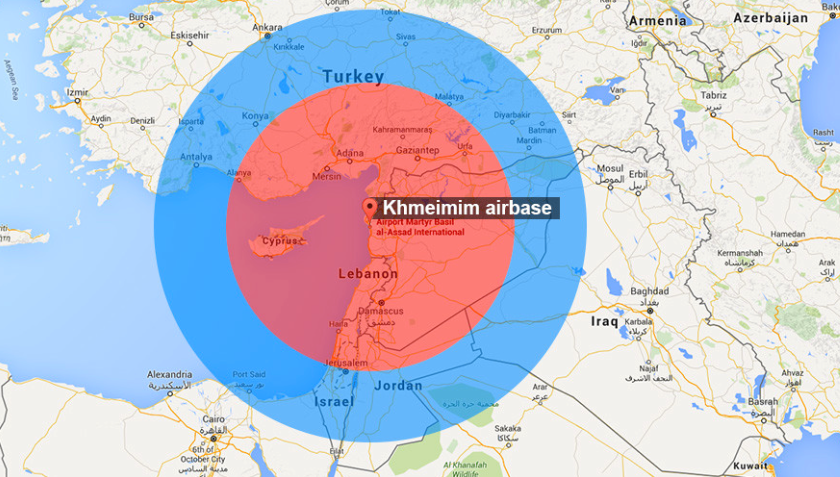

Beaton’s explanation is geopolitical – military, not economic. Summarizing the defeat of the KKE in the civil war following the defeat of the Germans, he concludes “there was never any serious prospect that Stalin would lend more than token, and ambiguous, support to the embattled communists in Greece…. Stalin chose not to antagonize the British, or later the Americans, over Greece for exactly the same reason that Tsar Nicholas I had chosen not to antagonize the western European powers by supporting the aims of Kolokotronis and the ‘Russian party’ a hundred years before. Events had shown, again and again, that control over Greece depended on a strong naval presence in the eastern Mediterranean. Except very briefly, during the 1770s, Russia had never been in that position, and certainly was not in 1944. Russia’s strategic priorities in the nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries (and indeed now, with the Soviet Union long gone, in the twenty-first century) have been entirely consistent.”

The lesson for Greeks, according to Beaton, is that Russians can promise, but without the military wherewithal, they will not make good because they cannot. The mistake Greeks make in believing otherwise is two centuries old. The corollary – the Russian conviction unstated by Beaton — is that the Entente (the 1920 term), or the US and NATO (today) will always occupy Greece militarily to forestall any change. Turkey on this geopolitical map is nothing more than a stick with which the Entente continues to beat Russia.

Does the map of the Eastern Mediterranean change, and everybody’s geopolitical calculations, when Gazprom’s Turkstream pipeline creates a Turkish hub for gas supplies to southern Europe; and when the Russian S-400 anti-aircraft missile system, already deployed on the Syrian shore, and soon to be at the Gaziemir Turkish Airforce Base, near Izmir, will cover in range all of Greece and the southeast coast of Italy?

Source: Gazprom

Source: http://warnewsupdates.blogspot.com/ For more analysis, read this.

It was in a message to Athens in October 2009 that then-President Dmitry Medvedev said: “Greece is our strategic partner with whom we share longstanding historical and cultural ties.”

Vladimir Putin has been more circumspect, and also more concrete. His closest Greek counterpart has been Kostas Karamanlis; they first met officially in 2001 when Putin was prime minister and Karamanlis leader of the parliamentary opposition. At the time Putin said “friendly relations between the two countries would continue to be a priority.”

They met again in Athens in 2005, when the Kremlin communiqué reported that “Greece and Russia share very similar views on a great many international issues. This concerns the situation in the Balkans and the question of a settlement for Cyprus.” But Putin’s priority, then and later, was to engage Greece in the import of Russian oil and gas, and become what the Kremlin was calling “an ‘energy hub’ with outlets to the energy markets of third countries, Russian gas supplies via Greece to countries in Southern and Western Europe, and the construction of an oil pipeline.” Their next meeting in September 2006 focused on terms for building the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline to carry Russian oil southwards through Bulgaria to Greece.

In December 2007 they met again. Putin declared: “Russian-Greek relations have always been built on the solid foundation of our peoples’ mutual trust and affection, and our partnership is of a genuinely friendly nature.” What Putin meant was conditional on energy strategy. He repeated: “constructing the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline is an important project both for Russia and for Europe. It will increase the supplies of Russian oil not only to Greece but to European markets generally. Vladimir Putin emphasized that Russia has chosen a draft project for the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline and will consistently implement it. The head of state also declared that Russia is ready to continue working with Greece within the Southern Stream pipeline project until 2040 and by doubling the volumes of gas delivered to Europe.”

Prime Minister Karamanlis with President Putin, Moscow, December 18, 2007

After their talks, Putin told the press: “I am confident that this visit will allow us to raise the bar of cooperation and partnership between Russia and Greece.”

Less than four months later, in April 2008, they met again: “It is a pleasure to meet once again in Moscow with the Greek Prime Minister, our old friend Mr Konstantinos Karamanlis….I want to emphasise that over the last four years, our relations with Greece have developed into a real partnership, and Russia places great value on this fact.”

In the event, almost everything Putin and Karamanlis planned together failed. The Burgas-Alexandropoulos pipeline project collapsed, in part because of opposition in Bulgaria (and Washington), in part because of the reluctance of Russian oil companies to deliver the oil; for details, click to read this and this. Putin agreed to re-route (and rename) Gazprom’s South Stream gas pipeline from Bulgaria and Greece to Turkey.

George Papandreou (left), who succeeded Karamanlis as prime minister in 2009, in Moscow in February 2010. The Kremlin regarded him as an American. Source: http://johnhelmer.org/

If not for the US putsch in Ukraine and the start of US and European sanctions against Russia in 2014, Putin’s rhetoric towards Papandreou’s successors would have remained cool. He told Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras in May 2016: “over these years of work together we have indeed developed very good and friendly relations. This helps us to find compromise solutions, of course, and it is always a big advantage to be able to count on the support of good personal relations when settling business issues.”

In fact, business was shrinking. So Putin revived traditional Russian ties with the Greek past. Ahead of a visit to Athens and the monastery at Mt Athos in May 2016, he told a right-wing Greek newspaper: “We value the centuries-old traditions of friendship between our peoples. Our cooperation rests on a rock-solid base of common civilizational values, the Orthodox culture and a genuine mutual affection. A vivid example of how closely our people’s lives are intertwined is the story of Ioannis Kapodistrias, who was a Russian minister of foreign affairs in the 19th century and later became a head of the Greek state…I know that Greece remembers that its achievement of independence was due in no small measure to Russia’s efforts. Russia’s support for the Greek national liberation struggle largely determined the further development of bilateral relations. These days, Greece is Russia’s important partner in Europe.”

It was Tsipras who revived the strategy cliché: “I would like to reiterate that our strategic choice is to strengthen ties with Russia, since our nations have historically close religious and spiritual bonds, and also because we have opportunities opening up in the future to build up our economic partnership, as well as to improve stability in the world and the region.” Tsipras repeated himself at a joint press conference with Putin, claiming the relationship was “a kind of cooperation that is a strategic choice for Greece. It is not only motivated by the deep cultural, spiritual and historical ties between our countries, but by being a component of any kind of Greek 21st century foreign policy in the globalised world.”

President Putin and Prime Minister Tsipras at the Greek Prime Ministry in Athens, May 27, 2016. Source: http://en.kremlin.ru/

Putin also revived the ancient ties. “We are perfectly aware of what kind of world we live in, and Greece itself is in a difficult situation. The Prime Minister has to make some very tough decisions, decisions that I believe are necessary but very difficult. We do not expect Greece to repeat the Labours of Hercules, and Greece is unlikely to clean the Augean stables of European bureaucracy… Yet Greece is the motherland of outstanding thinkers and schools of philosophy. I heard they found Aristotle’s grave here recently. In this regard, we certainly believe that, given our very warm relations going back many centuries, this is a good foundation for Russian-Greek relations. And we think that Greece can certainly contribute to and influence decision-making in the European Union and with the neighbours, especially if it initiates and creates conditions for implementing large regional projects.”

Lifting the ancient Greek out of his grave is proving to be more memorable to the Kremlin than burying the modern ones. The rhetoric cannot camouflage the extent of the strategic shift by the Kremlin towards Turkey, reinforced by trade and investment, and by confirmation of Turkey’s role in the export of gas to southern Europe. The demonstration of Russian air superiority over Syria, the success of its ground operations there, and the S-400 sale to Turkey have left the Tsipras government with nothing but recriminations towards Moscow, and a return to overt US military protection.

That Russian strategy can move in the Turkish direction is not new. But in two hundred years such a move has never proved sustainable over time: this is plain from Beaton’s history, as is Stalin’s suspicion of the “Kemalists”; no communist would have tolerated the Kemalist lobby operating inside the Kremlin today. For such a break with the past, there’s neither a Greek nor a Russian guide book.

Leave a Reply