By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

Last month the Russian metals and mining oligarch, Alexei Mordashov (lead image, left), took a spectacular pratfall in front of the international money markets. Not even hand-holding by Citigroup, JP Morgan, Credit Suisse, and Bank of Montreal could save him from the public embarrassment.

On June 3, Mordashov and the banks announced his intention to sell shares in his goldmining company Nordgold (Nord Gold PLC) on the London Stock Exchange, telling investors that future demand and the price of gold, and hence the profitability of Mordashov’s company, are bound to be boosted because of “possible inflationary pressures in the medium term from an exceptionally low interest rate environment and the possibility of currency revaluations, including U.S. dollar depreciation”.

On June 22, Mordashov got a Nordgold executive to announce the share sale was cancelled for the foreseeable future. His reason was that “acceleration in expected interest rate rises have created significant uncertainty and volatility in the resources sector, in particular impacting gold and gold equities. Nordgold has determined that it would therefore not be sensible to pursue an IPO at this particular juncture.”

If inflation was good reason for buying shares in Mordashov’s business at the start of the month, and then in less than three weeks Mordashov’s reason for not selling the shares, then Mordashov has made a fool of the market and a liar of himself. “That has to be bullshit,” responded a leading London mining analyst, who believes Mordashov’s vanity is to blame for imagining his shares would fetch a higher value in the market than share-buyers are willing to pay; and also Citigroup, JP Morgan, Credit Suisse, Bank of Montreal and the other bankers and brokers involved who were “too afraid to give him good advice on pricing.”

There is one thing more laughable in this episode than that. This is the effort which the Russia-warfighting media in London – for the first time combining Rupert Murdoch’s Times newspapers with Ian Hislop’s Private Eye — to make the failure of the share sale attempt appear to be an act of “British policy towards Putin and Russia’s rich”, in the words of Private Eye — as symbolic as the voyage of HMS Defender across the Crimean red line on June 23, the day after Mordashov and his bankers took their tumble.

Nordgold’s initial public offer (IPO) was unusual because not a penny of the share sale was proposed to be invested in the business.

Instead, Mordashov admitted he was asking investors to give him about $1.25 billion cash for his 25% stake in his company. He proposed to put the money in his own pocket, and invited the minority shareholders to trust him to keep control of the business. This requires not only trust in Mordashov’s new prospectus, but also ignorance of his record for losing large sums of investor money in the past.

Read the story of how Mordashov acquired Nordgold by buying control of Canadian and Guinean goldmines at a disadvantage to their shareholders here.

Left: December 2012

Right: October 2010

Next, read Mordashov’s record for running his steel, coal, timber, tourism, and other businesses in Russia at a profit for himself, and a loss for others.

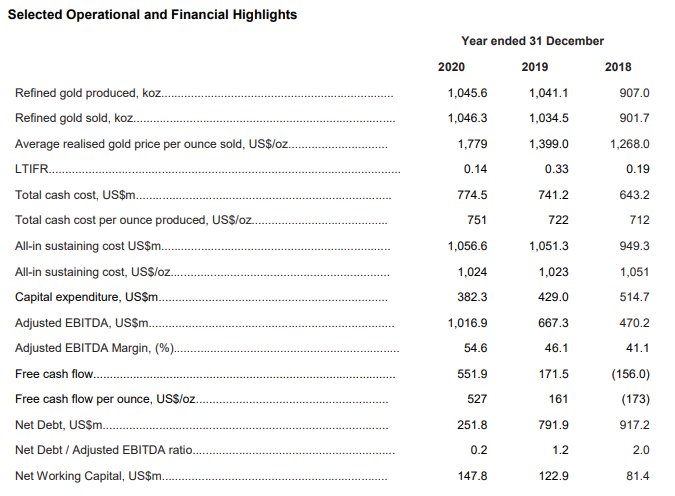

The reward in Mordashov’s newest pitch for investor trust, he said in the prospectus, was the promise of a payout to shareholders each year, starting in 2022, of “a minimum dividend of US$400 million which will be paid in 2 equal instalments following the release of the interim and full year 2021 financial results. With effect from 2022 financial year, Nordgold intends to pay minimum dividends equivalent to 50% of the Group’s free cash flow, pre-growth capex, subject to Net Debt / EBITDA remaining under 1.5x.”

The small print in the offer reveals that 50% of Nordgold’s free cash flow in 2018 would have been minus (repeat minus) $78 million; in 2019 it would have been plus $86 million; in 2020, plus $276 million. Going back into Nordgold’s past history by reading the story archive and the company’s financial reports since Mordashov sold a 10% shareholding publicly in 2011, there has never been a year in which its free cashflow (FCF) reached $400 million – let alone the $800 million target required for Mordashov to make good on his promise.

There’s also reason to expect that, since Mordashov will not be using any of his share-sale proceeds to invest in expansion of the gold prospects he is promising to increase proven reserves, mine production, and company profits, Nordgold will be borrowing heavily. That means the company’s debt will go back to where it was in 2018 or 2019. As the table reveals, if Mordashov does that, his debt-to-earnings ratio will rise above the 1.5x trigger at which the dividend promise will be shelved.

Source: https://nordgold.com/

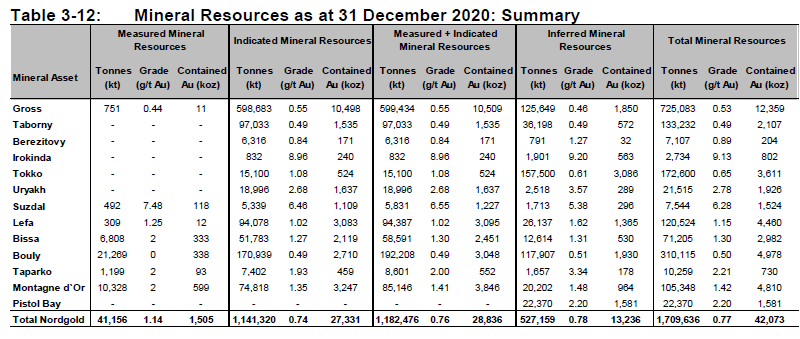

The hidden snare in this is that if the company doesn’t start borrowing to reverse its 26% cut in capital expenditure since 2018, the gap between current proven gold reserves and estimated future reserves will grow. Mordashov has past form for making empty promises like this. In 2010-2011, when Nordgold was making its international market debut, there was a gap between proven and probable gold reserves at 8.95 million troy ounces – most of them in west Africa – and inferred or projected resources at 22.11 million oz, amounting to 13.16 million oz; for details, read this.

According to last month’s IPO promise, Nordgold claimed that as of December 31, 2020, it had “15.2 Moz of proved and probable gold reserves and 42.1 Moz of measured, indicated and inferred gold resources.” This means that in the interval of a decade, the company has managed to increase its real stock of gold underground by 70%, but the gap between this and the promise of El Dorado has doubled; it now amounts to 26.9 million oz.

The geography of Mordashov’s promise has been changing, however. A decade ago, roughly half of the promised gold was in Nordgold’s mines in West Africa; the other half in Russia and Kazakhstan.

Now most of the promised gold is in Russia – this reflects the development of the Gross mine in fareastern Sakha (Yakutia) and the adjacent Tokko prospect.

Source: Prospectus, https://nordgold.com/ – page 380.

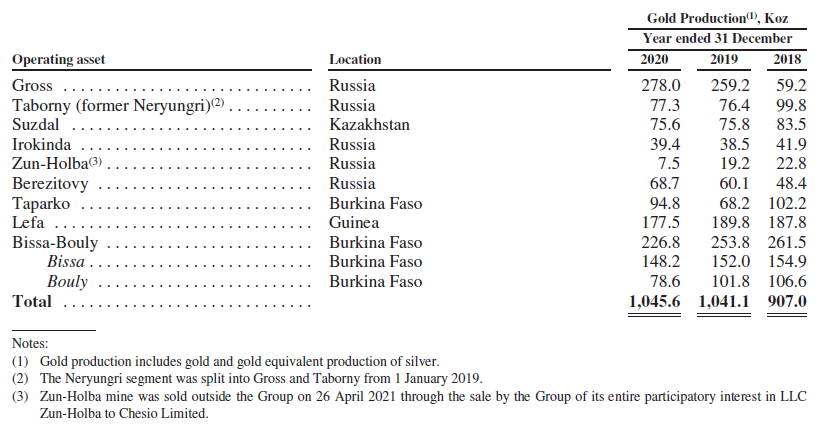

The company’s current gold production figures also show the declining importance of the West African mines compared with the Russian ones.

Source: Prospectus: https://nordgold.com/ – page 48.

In the small print of the prospectus (page 8), Mordashov acknowledges that increasing output of gold at Gross by 130,000 oz and at Tokko by 220,000 oz – a 32% rate of growth – will require at least half a billion dollars in new investment; even that may be an under-estimate. “The total start-up mine construction capital expenditure on the development of the Tokko project is estimated to amount to approximately U.S.$340 million during 2022 — 2024 and on the second stage of Gross expansion to approximately U.S.$ 208 million during 2021 — 2023… Information related to future operational results, capital expenditures, operating costs, TCC [total cash costs] and AISC [all-in sustaining costs] for the Gross expansion and Tokko development are preliminary estimates of the Group. The Group has not yet conducted feasibility studies related to these two projects and, as such, these estimates may change, subject to such studies being carried out.”

Mordashov didn’t ask the London market to stump up the money to pay for the promise of more gold, more profit by buying his shares. Instead, he told them, “Nordgold is not receiving any proceeds from the Offer.” He also admitted that he was aiming to achieve a target share price against which he planned to borrow in future. “The Board of Directors”, Mordashov announced about himself, “ believes the Offer and Admission [to the London Stock Exchange] will position the Group for its next stage of development by strengthening the Group’s capital structure by giving it access to a wider range of capital raising options which may be of use in the future, in particular to fund the Group’s future development plans” – in other words, borrow past the dividend payout trigger.

Reuters was told to report that Mordashov’s target valuation for the company was $5 billion, so he was hoping to trouser $1.25 billion for 25% of his shares. Two anonymous sources close to Mordashov’s deal, according to Reuters, said “the company could seek a valuation of anywhere between $4 billion and $5 billion, based on earnings multiples at which rivals such as Polyus Gold, Polymetal and Petropavlovsk trade. That suggests the IPO deal size could be between $1 billion and $1.25 billion, though one of the sources said it could be even higher. ‘Nord Gold is slightly different because half its operations are outside Russia, but based on where these companies are trading it could easily achieve $5 billion (valuation) and it only becomes a matter of what discount you want to offer,’ the source said.”

Polyus, owned by Suleiman Kerimov and his family, is currently listed on the Moscow Stock Exchange with a market capitalisation of Rb1.92 trillion ($26 billion). Its share price to earnings (PE) ratio is 10.5x. Polymetal, controlled by the Nessis brothers, is worth £7.5 billion ($10.4 billion), with a PE of 9.7x. Petropavlovsk is much smaller, and since its co-founder Pavel Maslovsky was jailed, finally, on fraud charges last December, its value is plummeting; for the Maslovsky story, read this.

If Nordgold’s target valuation was what Mordashov said it was, then its PE ratio between the $5 billion valuation and its 2020 earnings of just over $1 billion came to just 5x – that is half of its Russian peers Polyus and Polymetal; and much closer to the PE of 3.5x for Petropavlovsk. Since this reflects the Maslovsky discount, the weakness in last month’s Nordgold valuation reflected a comparable discount for Mordashov. But even that proved to be too small to attract share-buyers. As the chart shows, they have been steadily running the price down of the major Russian goldminers for a year now.

TOP RUSSIAN GOLDMINERS – SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY OVER THE PAST YEAR

KEY: black=Polyus; yellow=Polymetal; brown=Petropavlovsk.

Source: https://markets.ft.com/

The falling line might be interpreted as following the trajectory of the gold price over the same period.

GOLD PRICE JULY 2020-JULY 2021

Source: https://www.mining.com/

The chart of the goldmining peers of the US and Canada shows a similar trajectory except that they have not performed as well as Polyus and Polymetal.

TOP NON-RUSSIAN GOLDMINERS – SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY OVER THE PAST YEAR

KEY: black=Barrick Gold (market cap $38.8 billion); yellow=Kinross Gold; ($8.2 billion) orange=Newmont ($49.5 billion)

Source: https://markets.ft.com/

On current market capitalisation of the leading goldminers, Russia’s Polyus ranks third after Newmont (US) and Barrick (Canada).

According to a leading mining analyst in London, Nordgold’s announcement that inflation is to blame for the decision to cancel the IPO is as unbelievable in the market as Mordashov’s attempt to sell a $5 billion valuation for his company, and take all the proceeds for himself. “There are mining deals left, right and centre. It’s highly likely he did not get the fat valuation he instructed [Nordgold CEO Nikolai] Zelensky to get him, now for the third time. The bankers were too afraid to give him good advice on pricing. I’m also guessing that many London institutions are tired of this deal being wheeled out every few years.”

Russian goldminers are reluctant to comment on Mordashov’s misfortune. One commented: “in the past Mordashov carefully arranged permission for his big offshore moves by meeting [President Vladimir] Putin in advance. This time round he didn’t do that.” Mordashov has continued to be a regular at the President’s annual Christmas party for oligarchs, but it is now three years since Putin granted Mordashov a face-to-face meeting; that one was focused on steel and coal mining. At none of Putin’s meetings with Mordashov over the past decade has the official record of their conversation ever touched on goldmining.

February 21, 2018: source -- http://en.kremlin.ru/

On their discussions before Mordashov’s ill-fated attempt to buy the leading European steelmaker Arcelor in 2006, read this. For the Kremlin list of Mordashov’s meetings, click.

However, no Russian believes that the London media campaign for war against Russia had anything to do with Nordgold’s fate. The campaign started on June 6, just after the IPO plan and prospectus were released, with a false banner headline in Rupert Murdoch’s Sunday Times.

Source: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/

The reporter Jamie Nimmo had not written about Mordashov before, nor about goldmining. He also hadn’t seen the positive PR feed which two other colleagues in the same office published on June 4 and again on June 11. Nimmo also didn’t know that for months the Times has been exceptionally enthusiastic about the Tui travel and tour group in which Mordashov is the largest shareholder. When Nordgold announced it was cancelling the IPO, the Times report stuck to the company’s version and ignored Nimmo’s political “alarm”.

The Mining Journal cribbed much of its speculation on Nordgold’s reason from the Times, expressing skepticism at the reasons Nordgold had announced publicly. “Was it really all about gold price volatility in the light of the Fed’s more hawkish stance on interest rates, or was something else involved? And blaming a 6% fall in the gold price over a couple of weeks doesn’t quite stack up in a world where prices can seesaw like that in the blink of an eye.” The Mining Journal reporter relied on a New York think-tank and its expert on Alexei Navalny to find the same warfighting reason for Nordgold’s failure as the Times had done.

So did Michael Gillard, the author of Private Eye’s “In the City” column. Gillard, father and son writing under the same byline, have been Russia-haters for years; their record for misreporting Russia-related stories can be followed here. In the Eye, published on June 11, Gillard began his story on “Moscow’s Golden Ticket” by linking Nordgold to the Litvinenko, Skripal, and Navalny cases, and the Russiagate allegations in the US. “Despite worsening relations with Russia – which was accused last week of ‘aggressive behaviour’ by foreign secretary Dominic Raab, not to mention the odd poisoning or hacking – London’s bankers, lawyers, accountants and even regulators are still open for Russian business”.

The Nordgold share sale alarmed Gillard for the same political reasons as Nimmo had reported in the Times a few days before. “This comes at a time when politicians here and in the US are talking of pressurizing [sic] President Putin by further restricting the ability of Russian companies to use western markets and curbing the role of London in facilitating the movement of Russian cash around the world.” Gillard, who reports he had read the Nordgold prospectus, found next to nothing on goldmining. He did notice, however, that a power engineering company of Mordashov’s had been sanctioned by the US, and that there was a name link between Nordgold’s board and that of EN+, which has belonged to Oleg Deripaska, also sanctioned by the US. For the story of Mordashov’s Power Machines which Gillard missed, read this.

Gillard missed an even bigger story when he opened his June 25 sequel on Mordashov, “Stainless steelmaker”. This starts with the line that because “the US President had described Putin as a killer…it is perhaps [sic] not surprising to see the London operations of two major US banks leading the charge to further enrich one of Russia’s richest men, multi-billionaire Alexey Mordashov and his family, by orchestrating the planned sale of at least 25 percent of their shares in London-based Russian gold miner Nord Gold.”

Gillard ended his second report with the line from the Times: “the Nord Gold flotation still raises questions about British policy towards Putin and Russia’s rich at a time when the government and many Tory MPs talk about not facilitating Russian business interests”. The one question Gillard failed to raise himself on June 25 was why the Nord Gold share sale had been cancelled three days earlier. He didn’t know.

Leave a Reply