By John Helmer, Moscow

Paul Dibb, the former head of two Australian spy organizations and a deputy defence minister, has just published a call for Australian troops to be ready to fight in Europe against “Russia’s refusal to act in ways consistent with international law and standards of behaviour.” Dibb is known in Australia as “the country’s leading Cold War Russia expert.”

The Dibb report appeared on June 29, on the eve of last week’s Australian parliamentary election, when voters repudiated incumbent prime minister Malcolm Turnbull. He had called the snap poll, confident of expanding his majority in the two houses of parliament. He has now suffered a 3% negative swing by the voters; the loss of at least 23 seats; and months of political uncertainty ahead, including the possibility his party will replace him as leader.

Among Turnbull’s last-minute ploys to attract votes, one was the leak last month of Australian cabinet plans for an Australian Army force to fight in eastern Ukraine, alongside Dutch and other NATO units, to destroy the Donetsk and Lugansk rebellion against the regime in Kiev. Turnbull’s leak had suggested that Tony Abbott, the prime minister Turnbull had pushed aside to take the job, dreamed up the plan of Australian war at the Russian frontier by himself. The new report by Dibb now corroborates the idea of an Australian military expedition against Russia, in exchange for improved American commitments to defend Australia from the Chinese closer to home, in the Pacific. “How things work out in Europe,” Dibb claims, “ will affect Washington’s ability to reassure allies and partners everywhere, including those in our region who must contend with increasing coercion by China.” Unless Australia does more fighting with the Americans on the Russian front, he concludes, “China will take advantage of this, and allies and partners of the US in the region—including Australia—would be subject to further uncertainty about American military commitments to Asia.” Combating “Russia’s aggressive military behaviour “is necessary because, otherwise, “both Moscow and Beijing will be seen as getting away with it.”

The 40-page Dibb report is entitled “Why Russia is a threat to the international order”. Read it in full. The publisher is a think-tank headquartered in Sydney called the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). It says “ASPI was established, and is partially funded, by the Australian Government as an independent, non-partisan policy institute.”

The institute’s financial reports reveal it is financed by grants from the Australian Department of Defence, the Australian Army, the Australian Federal Police, the Dutch Foreign Ministry, and the Japanese Government; plus Raytheon, Northrup Grumman, Lockheed Martin, and Boeing — the leading arms-exporting corporations of the US. European arms builders also funding ASPI include the European missile-maker MBDA, BAE Systems, ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems, Rheinmetall, Airbus, and Navantia, the Spanish state shipbuilder. When Australians march into the field against the Russians, these suppliers aim to provide the best kit Australian money can buy.

Australian historians and military analysts say the idea that Australia is a military protectorate, for which it must pay with troops for its protector’s wars thousands of kilometres from Australian territory, is almost as old as the colonial settlement itself, once British troops were confident the convict settlers would not rebel. On British order, Australian troops were committed to the Sudan war in 1885; the Boxer rebellion in China in 1900; the Boer War in South Africa between 1899 and 1902; the war against Germany and Turkey in 1914, the war against Germany and Japan from 1940; and the war against the Malayan insurgency in 1948.

An Australian unit under British command in China, 1900. Source: http://aussiesatwar.com.au/conflicts-battles/boxer-rebellion/

The only time Australians prepared to fight against Russians directly was also on command from London; that was in the Crimean War of 1854, when units of cavalry, infantry and artillery were mustered in Sydney.

On order from Washington, Australian forces have fought in Korea, Vietnam, Kuwait, Iraq, and Afghanistan, as well as participated in spetznaz operations with the Americans in Africa. For case studies of these engagements and the Australian strategizing that led to them, read this. The conclusion: “The pattern, both before and after 1901, was much the same – no immediate direct threat to national security (except from Japan), popular enthusiasm at least initially, little if any parliamentary debate, haphazard preparation, and a minimum of formality, such as declaring war or debating it.” Tony Kevin, a former Australian ambassador to Poland to Cambodia, has described the process as one of loyalty, not legality : “We go to war when our cousins do.”

What is new, according to former Australian ambassador to Vietnam and Korea, Richard Broinowski, is that under the American protectorate, “to remain in good standing with the US, explicit acts of support are required from time to time, the more regular and the more extensive the better.” Paul Barratt, a former permanent head of the defence ministry in Canberra, has explained how Australian war-fighting evades public scrutiny, parliamentary vote, and a constitutional declaration of war. “A decision to send troops remains the prerogative of the executive — that is, Cabinet, meaning in practice the Prime Minister and a very small group of key ministers — an arrangement which means that a decision, once taken, can be acted upon without significant debate.”

This also means that war plans are decided and put into action in secret. The plan for an Australian force of up to 3,000 troops to fight in Ukraine in 2014 was revealed by James Brown in a report issued three weeks ago. Brown is a former Australian Army captain and head of research at the US Studies Centre of the University of Sydney. Brown (below, left) is also the son-in-law of Prime Minister Turnbull (right).

For the Ukraine operation Brown has reported the “planning for these military options consumed Australia’s intelligence agencies. The National Security Committee of [the Australian ministerial] Cabinet met every day for more than three weeks , and staff and agencies produced a frenzied stream of briefings on Ukraine, Russia and the intentions of [President] Vladimir Putin.”

If not from his father-in-law – in 2014 Turnbull was a cabinet member and prime minister in waiting — how did Brown know? Brown refuses to clarify his sources. His report also conceals the involvement of Dutch, NATO, and US commanders in the Ukraine war plan. Was it possible for two prime ministers, the Australian and the Dutch, to start mobilizing for a combined operation on the Russian border without US and NATO participation in the planning? Brown will not say. He does claim that then-Prime Minister Abbott had been foolhardy in considering such a largescale force in broad daylight on an open battlefield at the Russian frontier. He prefers, he reported, Australian special forces operating with the Americans, in the dark. For the Brown story, read this.

Dibb outranks Brown in Australia’s warfighting hierarchy, and he has had years more experience in espionage and military operations against Russia. But he cites no inside knowledge of the National Security Committee’s “frenzied stream of briefings on Ukraine, Russia and the intentions of [President] Vladimir Putin.”

To answer his question, Why Russia is a threat to the international order, Dibb cites 53 references and 11 footnotes. Take out 3 references by Dibb to speeches of President Putin, one to the published Russian military doctrine of 2014, there are just 6 other references which qualify as Russian sources of evidence. None of them is direct, military or official. They are the commentaries of think-tank academic Sergei Karaganov, former Russian foreign minister Igor Ivanov, and a group of analysts from the Valdai Discussion Club.

As evidence of Russian intention, plan and strategy, just 20% of Dibb’s sources are Russian. The rest are UK and US sources, the most frequently cited of which is the Chatham House think-tank in London. The only serving military officer cited by Dibb is Philip Breedlove (right), a US Air Force general and the outgoing commander of NATO forces in Europe. Dibb footnotes himself more often for evidence of Russian threats than he cites Russian evidence.

The “why” in the Dibb report title turns out to be rhetorical, not inquisitive. His is an argument, not an investigation. “There can be no doubt”, Dibb reports, “that Putin’s Russia is now seeking to reassert itself as a major power. The outward symbols of this occurred as long ago as 2008, when Russia used military force against Georgia, although not very impressively. “ Dibb omits to discuss the preliminaries to the August 2008 fighting, or identify ex-President Mikheil Saakashvili who moved first.

In his assessment of the Ukraine front, Dibb omits the removal of President Victor Yanukovich in Kiev in February 2014; the terms of the Ukraine-Russia base agreement for Crimea; and the Crimean referendum. Instead, “Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea and its attempt through military means to detach the Donbass region in the eastern part of Ukraine have to be seen as a fundamental challenge to the post-Cold War sanctity of European borders.”

On the Syrian front, according to Dibb, “Russia’s use of military force in Syria is a clear demonstration of Putin’s aggressive conduct of foreign policy” – no mention of US, Israeli, Turkish, Saudi, and NATO attempts to remove President Bashar al-Assad.

Dibb also applies passive reflexive syntax and no names for the top-secret intelligence that Russia is at war with the US itself. “Russia is believed to have used cyberattacks in 2015 to exert pressure on Ukraine by shutting down the electrical grid in the west of the country for several hours. In July 2015, cyberattacks thought to originate in Russia harassed the US Government. This included hackers successfully obtaining sensitive information from the White House and interrupting the Defense Department’s email system.”

Australian press reaction to the Dibb report has been muted. The Rupert Murdoch media claimed last week that Russian weapons sales to China “undermine Australian Defence Force technological advantage”. Another Murdoch publication, The Australian, reveals that Dibb has “lived a secret life working on behalf of ASIO [Australian Security Intelligence Organization] between 1965 and 1984 to penetrate the Soviet embassy in Canberra, identify which diplomats were KGB and GRU (Soviet military intelligence) agents and try to recruit them as informers.”

Dibb is now reported by The Australian as asking: “What if Putin suddenly put 150,000 troops with hardly any intelligence warning into one of the Baltic countries and NATO became involved — what would Australia do? If that happened, you can forget America’s pivot to Asia because it would pivot hard to Europe. What would that mean for us?”

The answer from Dibb is a call for Australian forces to be ready for action in Europe, when the call comes from the US and NATO. “All this points to taking the Russian threat more seriously… Our current security priorities focus on terrorism in the Middle East and the rise of China, as if nothing else is of national security concern.”

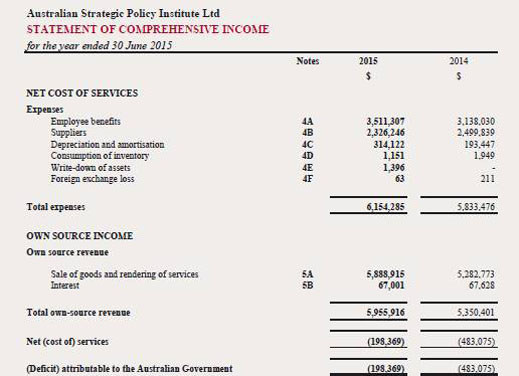

Responding to a 150,000-man Russian strike into Lithuania isn’t the only reason for urgency by Dibb and the strategists at ASPI. Last October, when the institute issued its financial report, the auditors revealed the organization, a limited liability company wholly owned by the state, was running in the red:

Source: https://www.aspi.org.au/about-aspi/annual-report/ASPI_AR1415.pdf

The ASPI balance-sheets show it has been in the red since 2012.

The money gap, according to the auditors, is “attributable to the Australian government”. However, in the small print the auditors have acknowledged the government has been in no hurry to pay. “ASPI is dependent on funding from the Department of Defence for its continued existence and ability to carry out its normal activities. The proposed new three year funding agreement (commencing 1 July 2015) with the Department of Defence has not been signed. The company has been in discussions with both the Minister and the Department of Defence in regard to this new agreement and is of the opinion that the company will continue to receive funding support past the expired funding agreement of 30 June 2015.”

Either the think-tank must cut its losses, meaning smaller stipends for Russia experts like Dibb. Or else it must appeal for bigger donations from foreign governments and weapons suppliers. The Dibb report makes clear which option he favours, but since he isn’t sure warfighting against Russia should become too public, he muffles his message.

“I’m not arguing here,” Dibb summarizes, “that we should earmark [sic] elements of the ADF [Australian Defence Force] for possible combat in Europe in the event that Russia attacks—for example—one of the Baltic countries. But we do need to think through what our response would be, if any [sic]. We’ve been willing in the recent past to contribute to NATO operations to address shared challenges, including in Afghanistan. The question here is: would the interests of NATO members and Australia align sufficiently in the event of a Russian attack against a NATO country?”

Another rhetorical question, to which Dibb gives a camouflaged yes.

The warfighters in Canberra aren’t convinced. The ASPI management, having decided to publish Dibb’s report, issues this warning in the small print: “No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional person.”

Leave a Reply