By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

In November 2001—twenty years ago — I gave a lecture in Moscow entitled: “Stealing the Truth – How to Read, and Not to Read, the Press In Russia”. The text has been lost. I am grateful to Ajay Goyal, the organiser of the Hellevig Lectures, for inviting me to bring the message back to life.

In the interval, Jon Hellevig lived his productive life in Russia. He and I both wrote for The Russia Journal and he set many examples of disciplined investigation leading to fearless publication of the truth. I salute him and his memory for what he achieved as an example to those of us who knew him and who live on.

In Soviet days, Russian reporters, editors and readers had shared an understanding of how to write and how to read the real message, the truth, between the lines of the printed text. This was a subtlety western readers have taken time to learn. The invention of the tweet struck with blunt force trauma; its unsubtlety came later. Then the US and the NATO allies opened the Ukraine front of their war against Russia in February 2014; the economic warfare sanctions followed the Ukrainian plot to down Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 in July 2014; the war on the Syria front escalated from September 2015; and the two Novichok operations were launched — the British one involving Sergei Skripal in March 2018, and the German one involving Alexei Navalny in August 2020.

In wartime, with Russia and the truth about Russia under the gun, you will understand me when I say I shall not allow my remarks to give aid and comfort to the other side. What I have had to say about domestic and internal Russian politics and the features of the Russian oligarchy are in print for all to read. There will be more to say — though not here, not today.

It is regrettable that the non-Russian investigations of these war operations are being carried out today by so few: a half-dozen bloggers in English on the Skripal case, for example; another half-dozen bloggers in English and Dutch on the MH17 story; less than this number in German on the Navalny case. Call us retailers of the truth, organic brand, NO additives, NO taste enhancers, NO artificial colouring. We are all excluded from the Anglo-American, European and Canadian mass media – call them the lie retailers, hypermarkets of additives and artificial colouring.

In the Russian market the media ignore us and favour instead state-financed operations from RT to Tsargrad and Vzglyad; the quality of investigative journalism varies enormously between them. Of course, the regime-change Russian opposition media ignore us too. If they don’t counter-attack us on cue from Bellingcat.

On the other side, the state-financed propaganda operations have tarred us with tags like “truther” and “Kremlin troll”. In this Lithuanian history of the term Kremlin troll, it appears to have begun in western propaganda operations in late 2014. For the history of the term truther, read this US account. These are propaganda terms, not analytical ones; they are intended to evade or discredit evidence of the truth by pinning us, like the tail of the donkey in the children’s game, to the other side.

An extreme example of this operation is the imprisonment of Julian Assange for having unlocked and published state secrets.

A conventional example of the operation is what a Canadian troll farm – on the other side, it calls itself a think tank – claims about my work in a report by an Estonian-Canadian who was paid by the Latvian Defence Ministry to report this. “John Helmer…initiated the January 2017 media frenzy around Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland’s grandfather’s involvement with the occupying Nazi regime in Poland during the Second World War. According to Maclean’s columnist Terry Glavin (2017), the story can be traced ‘through a maze of cranks, propagandists and Putin fanciers’ until it reached mainstream media. The story has been broadly identified as a Russian disinformation campaign. Recent articles on Helmer’s blog also promote other Kremlin positions, including the claim that the Skripal affair – which involved the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in the UK using the Russian Novichok nerve agent – was a UK government conspiracy to incriminate Russia” *

This isn’t the place to analyse the techniques of lying, faking, trolling, and truthering employed here. I’ve tried to do that in publications on better-known American and British liars and fakers, and in the cases of the Skripal, MH17, and Navalny operations. Enough to say that the Canadian evidence, verified by the Poles, is that Michael Chomiak, Freeland’s grandfather, spent World War II working at the liquidation of the Jews, Poles and Russians of the Galician region of western Ukraine and southern Poland, and to have prospered on the theft of the property of the dead. He had also been trained as a Nazi spy against his fellow Galicians. Freeland has been covering up for him all her life because she shares his goals but won’t admit to his methods. Canadian state policy towards Ukraine is the Freeland-Chomiak policy of Galicia.

But does revealing the truth and exposing the lies make the difference, inside and outside Russia, which Jon Hellevig hoped to accomplish in his writing, but which, at the end of his life, he doubted and despaired of?

Readers of tweet-sized journalism want to believe the answer is yes. They also want to read reinforcement for their conviction that they are on the winning side. The same dynamic operates to amplify the readership, and the subscription revenues, of a handful of American investigative journalists who publish through marketing platforms like Substack and Patreon. Investigative reporting on or from Russia does not rate on Substack, except that Matt Taibbi and Glenn Greenwald occasionally touch on Russia warfighting topics. Russia does not appear at all in Patreon’s top-100.

What professional journalist doesn’t want to believe that he or she is making a difference, as well making a decent living?

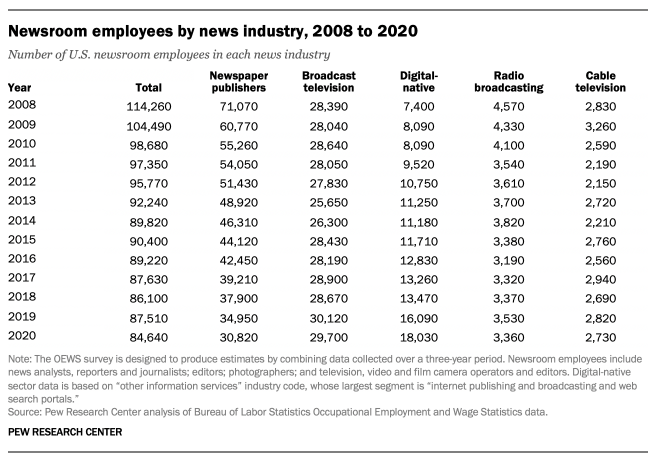

Still, if the truthfulness of journalism is correlated with the numbers of journalists making a living, then there must be much less truthfulness in publication than there used to be, Russia included. Even with the increase in digital media employment, the total of journalists today, counting conventional print, broadcast and digital production, is still 25% less than what it was in 2008, according to the US trend.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/

There is a significant offsetting number, but it is difficult to estimate. This is the growth of jobs in the think tanks of North America and Europe. The dominance of the US in the global think-tank market is obvious, but the deceleration of growth in US think-tank numbers in very recent years isn’t the measure that’s relevant. We need to know how much more money, especially state money, is flowing into these entities now, and what is the rate of growth of money and of think-tank writers as the US has escalated its war against Russia (China too).

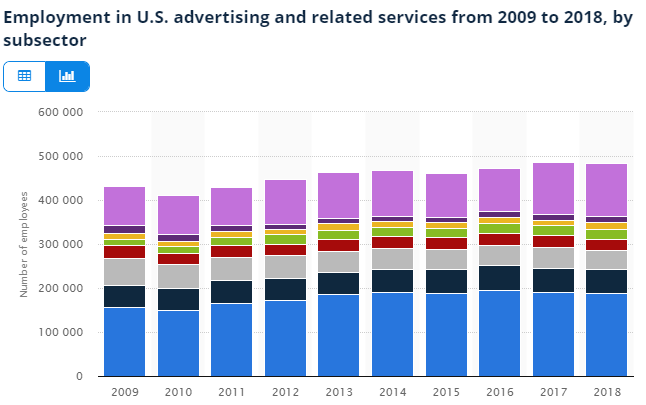

I believe the answer is that the employment and money value of the think-tank media is growing rapidly — individuals who would have once gone to work for conventional media now opt for think-tank media, which are higher paying and more stable in their employment prospects. The growth of think-tank “journalism” – I’m using inverted commas for the irony – is almost certainly on a faster and steadier trend upward than the growth of that other alternative for university-credentialled journalists – advertising and public relations. Between 2009 and 2018 employment numbers in that segment of the market grow by 12% — that is barely above 1% growth per annum.

Source: https://www.statista.com/

In the think-tank media market, note that Russia, while trailing far behind the US, is already matching Germany, and ahead of France, Italy, and Canada. As soon as you begin to count think tanks as a branch of state-financed media – let’s call them troll farms to be clear on both sides of the war-fighting lines — then the lying machinery of the US and NATO alliance, and the opposition of the Russian (and Chinese), may be better compared and measured for number, value, reach, and ultimately, not so much truthfulness as power.

Source: https://repository.upenn.edu/ – page 42

Naturally, the money supply for one side’s think tanks (troll farms) is directly linked to the amount of money being spent on the other side’s think tanks (troll farms). The same dynamic applies to spy agencies, arms builders, and chemical warfare laboratories: they all grow rich in proportion to the asset value, budget, headcount, and output of their adversaries. Fighting each other in the virtual, hybrid sense of war-fighting is what they all do for a living. This is how the power operates. This is not how the truth works.

But telling truth to power is a much less profitable enterprise, with much higher risks. As a result, the value and supply of truth will shrink compared to the value and supply of lies. In the marketplace this phenomenon has long been understood as Gresham’s Law – bad currency drives out the good. Think of think tanks or troll farms as the counterfeiters of bad pennies. Who in the next generation will be able to tell the difference? How will they be able to learn the difference at universities which house and sponsor these counterfeiters?

To students and to readers in general, I can’t recommend my experience as a guide to employment as a journalist. It is a guide to the risks we run.

Russia is only the last one of several revolutions I’ve lived and worked through in my career. By revolution, I mean not only a fundamental shift in the way power is exercised, but also a shift of the same magnitude in the way truth is interpreted.

I started as a member of the prime minister’s staff in the first Labor government to win an Australian election between 1949 and 1972. That government was overthrown in a putsch by pseudo-constitutionalists against political cowards in 1975. In 1977 I was a bureau chief in the Executive Office of the President when Jimmy Carter attempted his modest, but also revolutionary, attempts to reform US domestic and foreign policy. He was destroyed by Zbigniew Brzezinski and then by Ronald Reagan. I was private advisor to Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou, who revolutionized Greece between 1982 and 1989, when he lost an election, and was then destroyed by his lover. You might say I’ve had a career working for one political loser after another.

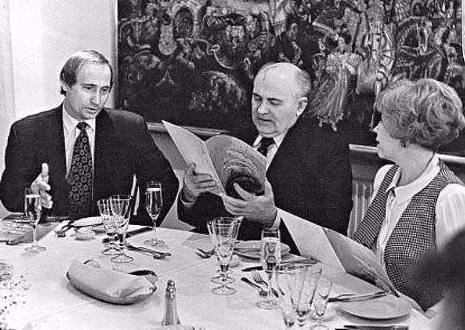

When I first came to Moscow for Papandreou in 1987, I had my doubts about Gorbachev; more about Raisa Gorbacheva, and even more about Eduard Shevardnadze. You know what happened to all three of them. But I stayed – like Dostoyevsky’s gambler, who is sure the next deal of cards, or the next turn of the roulette wheel, is bound to be the winning one. But until Vladimir Putin replaced Boris Yeltsin, Russia was dealing itself one losing hand after another, with cards whose corners had been cut by the NATO powers.

Vladimir Putin with Mikhail Gorbachev, Raisa Gorbacheva, 1994

I was also the first foreigner to own Russian land since 1917. I still have it. It’s 2.6 square metres of ground; it’s a grave in an old Moscow cemetery. It was there in 1993 that I buried someone I loved; she died of a sudden illness no Moscow hospital was equipped to treat at the time. Graves were the first Russian land holdings to be privatized. That was fitting, because Yeltsin arranged for misfortune to be privatized, first of all. And so I’ve experienced many of the terrible things that have happened to most Russians — death, theft of my home, threats of violence, contract fraud, corruption of the schools, courts, streets, hospitals, and media.

It is sometimes thought that Russian journalism – the work of my colleagues at Kommersant, Vzglyad and other newspapers of repute – is inferior to the western counterparts, and that western officials and companies are more transparent to the press. This is not true. In business, for example, the fact is that the media of the west are under constant manipulation by brokers, bankers, and touts trying to manipulate share prices. Wire services like Reuters and Bloomberg, newspapers like the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal, can and do print unsubstantiated gossip with the aim of boosting or dropping share prices by large margins, prepared by inside traders and speculators in advance.

How will the new generation discover these lessons, learn to read? Again, my experience is cautionary. When I introduced the first graduate-level course in investigative journalism at an Australian university, the course was in high demand for three years before student enrolment was stopped by the university, and I was removed. Graduates of that course who are now employed as reporters in mainstream media do not dare correspond with me by email through their company servers.

When money is at risk, business readers learn to read faster and with greater keenness. But now I do less investigative reporting of Russian business because it’s wartime. One of the immediate impacts of this war has been to drive Russian companies out of the New York, London. Hong Kong, and Frankfurt capital markets, and deter western companies from buying into Russian assets. In this process, Bloomberg, Reuters and the Financial Times have reversed their line but not their method. In the past, they lied and fabricated reporting for the benefit of the Russian oligarchs, their bankers and brokers. Now they lie and fabricate for the benefit of Anglo-American operations to sabotage and destroy all Russian business. The war has also encouraged secrecy and destroyed transparency on the part of Russian companies.

This lecture must come to an end.**

But there is no foreseeable end to this Russia war-fighting. In this war, truth was not only the first casualty, it will be the final one too, when the history of the war is written by the winners. Of course, in propaganda, information and cyber warfare our side is always winning; the other side is always losing. In truth there are no winning sides — and no reason for you and me to be confident that truth will win in the end. For one thing, you and I won’t be there at the end.

In the meantime, one of the rules of combat as the Germans, British and Americans have all practiced it, is that repeating a lie often enough will conceal the truth, erasing it as if it had never existed.

“When one lies,” Joseph Goebbels said of Winston Churchill’s “big lie factory” in 1941: “one should lie big, and stick to it.” Today, in the other side’s manual for reporting on Russia – the think-tank troll farms included — the rule is to multiply the little liars in the factory of the big lie, and stick to both of them.

This Finnish obituary includes Jon’s Hellevig’s obituary for himself, the song of Mercedes Sosa.

Our task – the duty Jon Hellevig asked us to remember – is to blow the roof off the factory and reveal what’s going on beneath.

[*] Marcus Kolga, “Stemming the Virus: Understanding and Responding to the Threat of Russian Disinformation”, Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI), Ottawa, January 2019. The author and the report were paid in part by the Defence Ministry of Latvia. This qualifies them as Latvian or Canadian trolls. For more on the author’s Estonian background, read this. Reporting on China by the MLI think tank is paid for by the Taiwan-Taipei government office in Canada and the Japanese Embassy, qualifying MLI as a Taiwan troll farm. MLI reporting on Covid-19 is paid for by the vaccine producers, including AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and the pharmaceutical lobby of the US, PhRMA. For MLI’s last published source of money report, click to read.

[**] For the lecture broadcast on YouTube, click to watch.

Leave a Reply