by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

“The immediate priority is to prevent the quick spread of this disease”, President Vladimir Putin (lead image, top left) declared in his state speech on the corona virus last week.

This is the point on which there is no disagreement, not now at least. But how restrictive for the economy the anti-contagion measures should be, and at what cost compared to the cost of the virus impact on life and death, is a point of considerable debate, inside Russia as everywhere else. That is the point which Putin avoided. He is not alone among the heads of state or government in the rest of the world. What is the difference then between Putin and all of them?

“Our most crucial task is to ensure stability in the labour market and to prevent a surge in unemployment”, Putin added in his March 25 speech, announcing a combination of small social welfare and employment compensation measures, with tax relief and loan deferment for businesses, and Central Bank support for “stable lending to the real economy, including through state guarantees and subsidies.”

Speaking in front of a plain wall, with symbols of nation, not of Kremlin nor of command, President Putin began his address on the virus. With a shrug of his left shoulder and an open gesture of his hands, Putin’s delivery was informal, almost fireside in style as US presidents have attempted it. US and British analysts who claim Putin “looked less in command than usual” mistook style for substance; in cribbing from Russian social media speculation about Putin’s health, they misunderstood both.

The subsequent meeting of Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin with his 9-member “Presidium of the Government Coordination Council to control the incidence of novel coronavirus infection” on March 27 spelled out the anti-contagion policies — especially in Moscow where two-thirds of the recorded cases are concentrated — with an attempt to show that mobilization of supply of testing and treatment measures will more than match the demand for treatment for infected cases. This is the anti-surge strategy, following the China model. The message is that there will be no Italian or Spanish course in Russia. There will also be no failures on the supply side – masks, tests, ventilators, intensive care beds – as there are in the UK, US, and France. Saying so explicitly is a policy designed to combat confusion down the line of command, and stop panic in the population.

The Prime Minister chairing the Covid-19 command with First Deputy Prime Minister Andrei Belousov at his right, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin at his left, and then in declining rank order, Mikhail Murashko, Minister of Health (2nd from left) and Anna Popova, head of Rospotrebnadzor (extreme left), both medical doctors; and on the far right, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov. Source: http://government.ru/

Mishustin referred to the government’s calculations for rapid testing and treatment, according to the state plan already drafted by ministers working under First Deputy Prime Minister Andrei Belousov; he was the chief economic advisor to Putin until Mishustin’s appointment in mid-January.

At Mishustin’s cabinet meeting, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin said “we have calculated the required number of hospital beds for every region [of the city]. We have stipulated clear requirements for buildings and hospitals that will be treating coronavirus patients: the number of respirators they must have, intensive care units, oxygen supply, etc., as well as general requirements for buildings, personnel and equipment. All regions have received these requirements in line with your instruction. I believe that most of them have actively launched this work.”

Putin had been at that point himself with Sobyanin two days earlier. Accompanied by the mayor and health minister, he visited the Kommunarka Hospital, where he was briefed by one of the leading medical policy-makers at the moment, Denis Protsenko.

Left to right: Denis Protsenko, Head Physician of City Clinical Hospital No. 40; the President; Mayor Sobyanin. Also in the briefing room were Deputy Prime Minister Tatiana Golikova, Health Minister Mikhail Murashko, and Rospotrebnadzor head Anna Popova.

“From a medical perspective,” Protsenko told Putin, “there are essentially two possible scenarios right now: the Asian one where the spread of the virus quickly subsides, and the Italian scenario with a growing infection rate. As a doctor, an anaesthesiologist and an emergency room practitioner, not just a chief medical officer at a clinic, I believe it is essential that we work [to prevent] the Italian scenario. If one day we see a major surge in infections, and Moscow is already moving in this direction, we are ready to convert this hospital to accommodate… At this very moment, we are ready to repurpose 190 of 606 beds to intensive care units. We are taking lung ventilators from storage and installing them, so these 600 beds can form a major intensive care clinic bringing together highly competent experts from across the city. This is what the Italian model is all about. If we suddenly shift to the Chinese or Korean scenario and it all ends in April or May, I think this would make our doctors happier than anybody. Still, I think we need to be ready to face a worst-case scenario.”

The Kremlin record also reveals that Protsenko has been working with Chinese doctors and planners on treatment therapies which the Chinese have tested for their effectiveness as the seriousness of case infections grows. “Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a technology that has returned to our ICUs from the operating rooms after the swine flu outbreak. The city has sufficient ECMO capacity, and an ECMO centre has been set up at one of our hospitals. Today, our department gathered for a roundtable discussion with our Chinese colleagues. They said that this time, unlike during the swine flu, the ECMO was not used that much at their hospital, with only 11 ECMO cases in a total of 6,000 patients.”

More than a month ago, in mid-February there was a semi-official announcement from Beijing that “Chinese experts, based on the result of clinical trials, have confirmed that Chloroquine Phosphate, an antimalarial drug, has a certain curative effect on the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), a Chinese official said here Monday. The experts have ‘unanimously’ suggested the drug be included in the next version of the treatment guidelines and applied in wider clinical trials as soon as possible, Sun Yanrong, deputy head of the China National Center for Biotechnology Development under the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), said at a press conference.” Thus did the Chinese put a stop to the bitter medical and political controversy in France over the efficacy of chloroquine in treating patients at the intensive care unit (ICU) stage. The controversy has also triggered panic buying of chloroquine in France and Switzerland. The case for and against Didier Raoult, chief promoter of chloroquine therapy in France, can be followed here and here.

Chloroquine has been one of several therapies tested and applied in China; it has not been a priority or a command protocol. A Chinese medical source comments: “Azithromycin and other antibiotics may be used for treatment of potentially superimposed bacteria infection. The main successful treatment in China so far is supportive treatment: remove the excessive secretions in lungs and ensure adequate oxygenation. The principles would be supportive measures plus broad anti-infective and anti-inflammation agents.”

Protsenko and other Moscow sources decline to say whether there is any disagreement among Russian medical specialists and the Health Ministry on the treatment therapies they are administering in Russian hospitals. There is no evidence of a Russian argument over chloroquine.

Putin’s visit to Kommunarka Hospital is remarkable in international terms. No head of government or of state in Europe or North America has been doing the same thing, donning protective gear, and receiving a detailed medical policy briefing at a virus treatment centre. Chinese President Xi Jinping is the only other international leader to have paid a hospital visit. Xi (lead image, top right) toured Huoshenshan, a pre-fabricated hospital in Wuhan constructed in ten days. Xi made his visit on March 10.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/

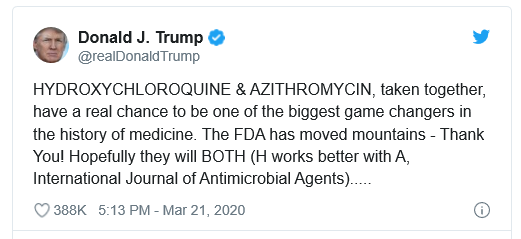

President Donald Trump made a public display of a different kind (lead image, bottom). On March 28 he gave a speech at the US Navy base at Norfolk, Virginia, in front of the Navy hospital ship, USNS Comfort. “I’m deeply honoured to be at Naval Station Norfolk,” he said, “the largest naval base anywhere in the world, and the home to the most powerful fleet that has ever sailed the seas. I just passed some of the most beautiful and, frankly, the most highly lethal ships that I have ever seen in my life, and there are a lot of them. And they’re in better shape now than they have been for many, many decades, with what we’re doing.”

A hospital ship for New York and one for California were reported by Trump. He also pledged to deliver Army-built temporary hospitals, plus “11.6 million N95 respirators, 26 million surgical masks, 5.2 million face shields — and a lot are being made of all of the things I just named right now; we have millions and millions of new medical items being made as we speak, and purchased — 4.3 million surgical gowns, 22 million gloves, and 8,100 ventilators.”

This was a military plan just short of requisition according to the Defense Production Act of 1950; it had been enacted for civil defence and plant mobilization at the beginning of the Korean War. In current terms, Trump is following the Russia-China model. But the president omitted to reveal how far behind the US is starting; for example, after thirteen years of efforts by the US Government to develop low-cost, easy to use ventilators, not a single one has been delivered. Trump has also tweeted in favour of the chloroquine therapy.

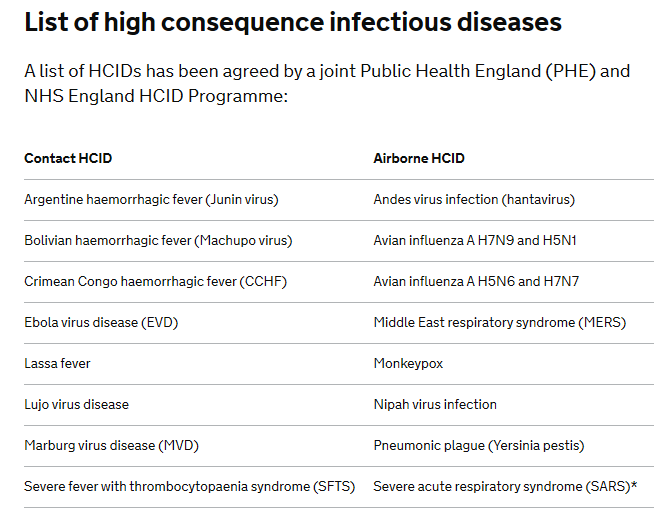

The British Government has ended up trailing in the same position — but not before Public Health England (PHE) issued the announcement of March 19, 2020, that “COVID-19 is no longer considered to be a high consequence infectious disease (HCID) in the UK…Now that more is known about COVID-19, the public health bodies in the UK have reviewed the most up to date information about COVID-19 against the UK HCID criteria. They have determined that several features have now changed; in particular, more information is available about mortality rates (low overall), and there is now greater clinical awareness and a specific and sensitive laboratory test, the availability of which continues to increase.”

The British list of high consequence infectious diseases, agreed between Public Health England (PHE) and the National Health Service (NHS), issued at the same time, is a ranking of much higher mortality rates than Covid-19; “high consequence” means, not high infection numbers but high casualties in proportion to the case numbers.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/

This downgrading of Covid-19 was reportedly backed by the Government’s chief science advisor Patrick Vallance, the chief medical officer Chris Witty, and Dominic Cummings, the prime minister’s chief advisor. “Under Sir Patrick’s initial modelling,” it was reported last week, “the disease would be controlled so that it remained manageable for the NHS [National Health Service]; a peak would be achieved in early summer. After this, thanks to population immunity, it would tail off and not recur at any scale next winter. It was the modelling which informed chancellor Rishi Sunak’s first Budget on March 11, which assumed a relatively short and sharp economic hit this summer, then a rebound. At that time a £12bn package of help was widely seen as generous; a few days later it was seen as painfully inadequate.”

By the time the PHE/NHS announcement was published, it was no longer the policy of Prime Minister Boris Johnson. He was persuaded instead by the Imperial College report, “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand” commissioned by the government. This projected in the UK the Italian model for the contagion of Covid-19; a surge of serious cases beyond the capacity of the hospital system to cope; and “high consequence” – a high death rate.

Financial Times headline, reporting the Imperial College study, on March 17. Referring to the PHE/NHS policy, “about 250,000 people would have died in the UK under the government’s previous strategy for dealing with the coronavirus crisis, even if the health service was able to cope with the surge in illness, according to Imperial College researchers”. For the FT’s summary of the report, read this. The case for mitigation is actively made in the British press and in the alt-media worldwide, based on large asymptomatic, mild and recovery numbers, low death rates, and the theory that the corona virus is no worse than seasonal influenza. For example: in the UK; Germany; Italy; Sweden; and in global summary. A report by a British doctor in Private Eye, published on March 20, concluded that according to the UK Office for National Statistics, “deaths are actually lower this year [to end-February] than the average for each week over the previous five years. I like to think it’s the hand washing.”

The 20-page Imperial College report can be read here. The recommendation for change of state policy was from mitigation to suppression. “Two fundamental strategies are possible: (a) mitigation, which focuses on slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread – reducing peak healthcare demand while protecting those most at risk of severe disease from infection, and (b) suppression, which aims to reverse epidemic growth, reducing case numbers to low levels and maintaining that situation indefinitely. Each policy has major challenges. We find that optimal mitigation policies (combining home isolation of suspect cases, home quarantine of those living in the same household as suspect cases, and social distancing of the elderly and others at most risk of severe disease) might reduce peak healthcare demand by 2/3 and deaths by half. However, the resulting mitigated epidemic would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (most notably intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over. For countries able to achieve it, this leaves suppression as the preferred policy option.”

The report’s calculations were based on the Chinese experience at Wuhan; the modelling assumptions to produce the calculations were not the Chinese ones. “Suppression, while successful to date in China and South Korea, carries with it enormous social and economic costs which may themselves have significant impact on health and well-being in the short and longer-term. Mitigation will never be able to completely protect those at risk from severe disease or death and the resulting mortality may therefore still be high…. while experience in China and now South Korea show that suppression is possible in the short term, it remains to be seen whether it is possible long-term, and whether the social and economic costs of the interventions adopted thus far can be reduced.” The evidence in Italy was not included in the study until a few days before publication. It was the Italian record, the report says, which led to the conclusion that “epidemic suppression is the only viable strategy at the current time.”

“The U.K. has struggled in the past few weeks in thinking about how to handle this outbreak long term,” Neil Ferguson, the principal author of the Imperial College report, told the New York Times. “Based on our estimates and other teams’, there’s really no option but follow in China’s footsteps and suppress.”

In the days following, Ferguson has tested positive for Covid-19. So have the Prime Minister, Witty, Cummings and Health Minister Matt Hancock.

Putin, Mishustin, the federal ministers and Sobyanin have not (yet) distinguished in their public statements between the strategies of mitigation and suppression. In Protsenko’s briefing at Kommunarka Hospital, he was explicit that Russia was following the Chinese model in order to avoid the Italian one. But among Russian epidemiologists, health economists, and planners, is there a debate over evidence or strategy?

According to Larisa Popovich (right), Director of the Institute for Health Economics at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, there has been no strategy debate or disagreement because past experience in civil defence had already decided the approach, and there has been rapid

reaction in early measures of population control, testing, and contact tracing. “Things are completely different for us [in Russia]. We reacted quite quickly: Border regions were closed off quickly, and we began isolating people. I’m also very happy that we still have a centralized service for epidemiological control [Rospotrebnadzor] which has worked extremely well. Plus, we’ve developed our own tests, which generate results within four hours, and mass production has already begun. In the near future, we’ll transition from testing people with symptoms to testing everyone with minor illnesses, and then testing will be available to anyone who wants it. This will help identify those who are asymptomatic carriers.”

This is a pointer to a crucial datum in Russian policymaking – the death rate is bound to fall sharply as the tested population expands. Restricting the numerator of serious cases requiring intensive care to the capacity of the hospital system to treat them effectively, while multiplying the denominator of tested positive cases produces a very low death rate, as the Chinese are reporting. It should also dampen panic, and shorten the duration of the regime of restrictive measures.

“Russia is better prepared,” said Popovich, “for the coronavirus than many other countries. Historically, we have experience fighting complicated forms of pneumonia and drug-resistant forms of pulmonary disease. We have a high prevalence of tuberculosis, and our doctors know how to treat respiratory distress syndrome.”

Are there standardized data for Russia, Popovich was asked, to measure the comparison with other countries – for example, for the rate of Covid-19 testing, the availability of ventilators, the number of intensive care unit beds?

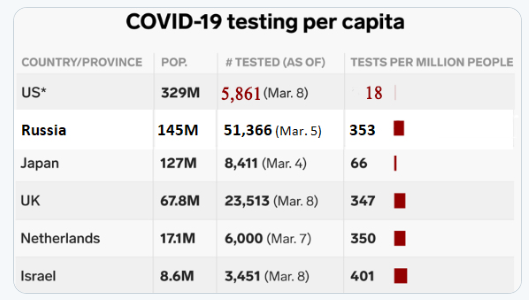

This tabulation was reported on March 11. Source: https://twitter.com/. In three weeks since, the volume of testing has more than tripled. By March 27 Rospotrebnadzor reported 223,509 tests had been conducted in the country.

Popovich and other Moscow experts are reluctant to commit themselves to the numbers. Press reporting, Health Ministry and Rospotrebnadzor releases suggest the supply of portable and fixed ventilators is better than in most of Europe or the US; and for the time being exceeds the demand for critical case treatment. Most country comparisons published for western Europe and the US do not show Russia at all.

Igor Molchanov, head of anaesthesiology and intensive care at the Ministry of Health, said on March 28: “with artificial respiration devices, we have everything in order today. Moreover, we have a certain margin of safety in this issue due to timely organizational decisions. For example, all planned surgical interventions were postponed, and there are quite a lot of them in Russia. Anaesthetic devices that were used for elective surgery are now released as a reserve: they can also be used to ventilate the lungs and do this for a long time. In the case of the coronavirus, we are talking about a short duration of lung ventilation, so no problems are expected with this. In terms of technical equipment, we are moving ahead and are ready to meet the existing challenges.”

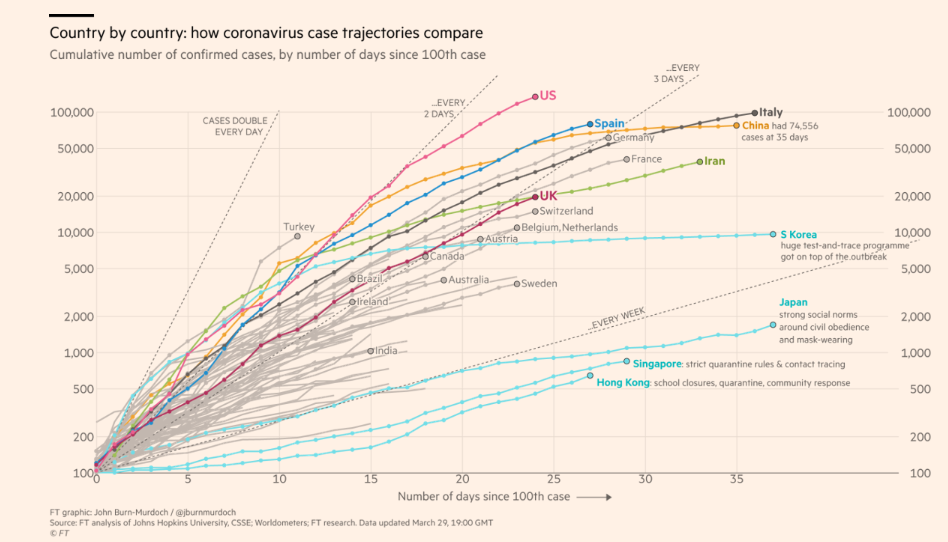

The following charts of case reports illustrate the prevailing difference between Russia and other countries. The first is the official case report for Russia, issued on March 30 for March 29, showing a countrywide total of 1,836; that was an increase of 302 new cases over the day before (+19.7% rate of growth). For Moscow, the aggregate was 1,226 (67% of the all-Russia figure), and the daily new case increase was 212 (+21%). The growth rate clearly indicates that Russia is now in the acceleration phase compared to a fortnight ago, but may already be slowing compared to March 25 (+29%). The death count was extremely low at 11 nationwide. The second chart was prepared by the Financial Times with data updated to March 29.

For enlargement and for viewing the data region by region, click to source.

Data updated to March 29, 2020. For enlargement of image, click to source.

For ventilators, according to published reports, Russia currently has about 45,000, and is planning to increase the number from local manufacturers by 5,700 by the end of June. This compares with the current US stock of 12,700. Even with the renovation of another 4,000, the US aggregate is “still fewer than a quarter of what officials years earlier had estimated would be required in a moderate flu pandemic.”

On March 28, Health Minister Murashko announced: “To date… Ministry of Industry and Trade has put into circulation a large number of masks; in total, they come to more than 30 million.”

As for the economic impact on the Russian economy of the Chinese model, or of what the British are calling suppression strategy, Putin’s national speech of March 25 focused on short-term labour market measures, compensation for the unemployed, and tax and debt relief for businesses to keep production from stopping. The priority, he assured, is to “ensure the social protection of our people, their incomes and jobs, as well as support for small and medium-sized businesses, which employ millions of people.” The measures he listed had come from Mishustin’s ministers who met to compile their list on March 21.

There has been no fresh meeting of economic policymakers at the prime ministry since then. The record of that meeting revealed the “Plan of Priority Measures to Ensure Sustainable Economic Development”, worked up by a commission headed by First Deputy Prime Minister Belousov. The Belousov plan, according to the prime ministry communiqué, comprised the labour market and bank lending support which Putin then announced.

There was a difference, however, between the Belousov plan and the Putin announcement four days later. This was two revenue raising measures which Putin revealed. The first was a tax on the export to bank accounts abroad of interest and dividends. “First, all interest and dividend income that flows from Russia and is transferred abroad into offshore jurisdictions must be taxed properly. Today, two thirds of these funds, and basically we are talking here about incomes of specific individuals, are taxed at the rate of only 2 percent, thanks to so-called optimization strategies of all kinds. At the same time, people with modest salaries pay an income tax of 13 percent. This is unfair, to say the least. For this reason, I suggest that those expatriating their income as dividends to foreign accounts should pay a 15 percent tax on these dividends.”

This is not the first time Putin has publicly declared that tax benefits enjoyed by those able to operate offshore capital and banking schemes are inequitable. This tax is the first thing he has done about it. Putin is the only head of state proposing to tax the wealthy to help defray part of the cost of the Covid policy outlays.

The principal policy defender of unregulated and untaxed capital outflows, Alexei Kudrin, formerly finance minister and currently head of the Accounting Chamber, has had nothing to say, yet. Before Putin’s speech, Kudrin said he is suspending new audits. “We cancel all new checks until June 1, and postpone them to a later date. During this period, we will only deal with the completion of old inspections.”

Leave a Reply