By John Helmer, Moscow

A combination of American and British commodity traders, aided by George Soros (lead image, left), is planning to oust United Company Rusal, the Russian aluminium monopoly, from its Friguia bauxite and alumina concession in the west African Republic of Guinea. The plan, according to sources in London and Conakry, the Guinean capital, calls for the Guinean President Alpha Conde to revoke Rusal’s production agreement, according to the recommendations of an inter-ministerial group of officials known as the Comité Technique de Revue des Titres et Conventions Miniers (Technical Committee of Review of Mining Titles and Concessions). Conde is being urged by Soros to replace the Russians led by Rusal chief executive, Oleg Deripaska (lead image, right).

The Gerald Group, according to a London source, has a double-barreled target, aiming also at Rusal’s control of the Nikolaev Alumina Refinery (NGZ) in eastern Ukraine. Defending Rusal from the attack, says a source close to Rusal, is Glencore, the Switzerland-based global commodity trader, which is a minority stakeholder in Rusal and the financier of much of its aluminium and alumina trade.

The Anglo-American group comprises the Gerald Group and the Reuben Brothers Resources Group (RBRG). Gerald is based in Stamford, Connecticut, where it was established in 1962 by Gerry Lennard. He sold out in 2003 to his chief executive, Lloyd Lander. On April 29, Lander joined forces with Mel Wilde (right), head of the London-based Reuben Brothers Resources Group (RBRG). The deal between the two private companies was reported here.

The Anglo-American group comprises the Gerald Group and the Reuben Brothers Resources Group (RBRG). Gerald is based in Stamford, Connecticut, where it was established in 1962 by Gerry Lennard. He sold out in 2003 to his chief executive, Lloyd Lander. On April 29, Lander joined forces with Mel Wilde (right), head of the London-based Reuben Brothers Resources Group (RBRG). The deal between the two private companies was reported here.

The release speaks of “creating a new Ferrous & Raw Materials division led by Mel Wilde within the Gerald Group. The Gerald Group headquartered in Stamford, CT [Connecticut], will absorb and integrate the entire RBRG Trading business and its people. This newly created division will become a core business of The Gerald Group from day one…and handle more than 10 million tonnes of iron ore as well as transact significant quantities of steel and other steel-making raw materials.” No other details of the deal have been published as Gerald and RBRG claim their “website is currently under construction”.

Sources close to Gerald say the new combination has proposed to the Guinean government to take over the Friguia bauxite and alumina concession currently owned by Rusal; assist in the establishment of a new management to replace the Russians at the bauxite mine; and restart the alumina refinery which Rusal closed in April 2012. Wilde and the Gerald-RBRG combination have proposed to raise finance for the restart of the refinery, and in part payment take the bauxite and alumina produced for international sale.

Wilde did not respond to questions at his office at the Millbank Tower in London.

Rusal operating reports indicate that in 2010 the Friguia bauxite mine turned out 2.1 million tonnes of bauxite, and 598,000 tonnes of alumina. Production was cut the following year, and since April 2012, the mine and refinery have been closed. Another 3.3 million tonnes of bauxite are mined annually at Rusal’s Kindia concession in Guinea. From Guinea the raw material is shipped to Nikolaev, where it is refined into 1.5 million tonnes of alumina, and then transported to Rusal’s Russian smelters to be converted into aluminium. Deripaska, who is also Rusal’s controlling shareholder, established this production chain between 2000 and 2004.

At the time, David Reuben (right), who headed the Trans-World trading group, fell out with Deripaska over who should control the Guinean concessions and the Russian smelters. Reuben testified in the UK High Court during the trial of Boris Berezovsky’s claims against Roman Abramovich that he hadn’t wanted to deal with Deripaska, but that he had been threatened and pressured into selling his Russian assets to him. Guinean sources add that Deripaska also took control of the Guinean concessions over Reuben’s claim to have negotiated them for his own group. Subsequent litigation between the two of them in the British Virgin Islands was settled out of court with a large payment in Reuben’s favour.

At the time, David Reuben (right), who headed the Trans-World trading group, fell out with Deripaska over who should control the Guinean concessions and the Russian smelters. Reuben testified in the UK High Court during the trial of Boris Berezovsky’s claims against Roman Abramovich that he hadn’t wanted to deal with Deripaska, but that he had been threatened and pressured into selling his Russian assets to him. Guinean sources add that Deripaska also took control of the Guinean concessions over Reuben’s claim to have negotiated them for his own group. Subsequent litigation between the two of them in the British Virgin Islands was settled out of court with a large payment in Reuben’s favour.

Sources in Conakry said this week that President Conde has ordered the restart of the Friguia alumina refinery. That decision was announced publicly at the start of July by the Guinean mines minister, Kerfalla Yansané.

According to a report prepared in Conakry by the Comité Technique de Revue des Titres et Conventions Miniers (CTRTCM), Rusal is in violation of the obligations it signed when it acquired the Friguia mine and refinery in a privatization by the government in 2006. The Technical Committee recommended to Conde and his government that they should “make a complete overhaul of Fria [Friguia] Project, and by pursuing three objectives: correct the deficiencies identified in the Audit Report, particularly with regard to the undervaluation of the amount received by the State on the occasion of privatization operations and procedures of operating Fria Project; resume and detail a number of pre-existing obligations to allow control of the execution [of the concession agreement] by Rusal Friguia SA and in the future; and settle the question of the applicable law and the tax and customs to retain through a complete harmonization of Fria Project with the new mining code regime.”

The report also implied that private negotiations, which have been conducted between Conde, his son Mohammed (right), Deripaska and his representative Victor Boyarkin, should be superseded in favour of a transparent agreement ratified according to Guinean law. The government, says the confidential committee report, should “conduct comprehensive updating of Fria Project through a new mining agreement fully subject to the new mining code rather than through an amendment to the paragraph 4 of the New Code under Article 217-I Minier 2011; [and] ensure that the new mining agreement is properly ratified by the National Assembly for its entry into force.”

The report also implied that private negotiations, which have been conducted between Conde, his son Mohammed (right), Deripaska and his representative Victor Boyarkin, should be superseded in favour of a transparent agreement ratified according to Guinean law. The government, says the confidential committee report, should “conduct comprehensive updating of Fria Project through a new mining agreement fully subject to the new mining code rather than through an amendment to the paragraph 4 of the New Code under Article 217-I Minier 2011; [and] ensure that the new mining agreement is properly ratified by the National Assembly for its entry into force.”

For details of Deripaska’s and Boyarkin’s dealmaking with Conde, click here. The Technical Committee reveals that it has been unable to obtain a copy of the official minutes of these talks, or of the text of whatever agreement was reached. The committee calls for Rusal to make “firm commitments” for the “restoration of the level of production of the plant and the subsequent expansion of production capacity.” Rusal papers indicate this means restoring the design capacity of more than 600,000 tonnes of alumina per annum, plus fresh capacity of 413,000 tonnes, making more than 1 million tonnes in all. This in turn would require a matching increase in bauxite from the Friguia mine.

The committee report expresses doubt that Rusal has the financial means or the will to make the required investments. “The financial difficulties currently faced by Rusal and their potential impact on Fria Project should be discussed with Rusal because the choice which could be made [by Rusal] to deprive Friguia SA of financial resources could be equated to a loss of financial capacity.” That, declared the committee, “would allow the State to withdraw the Mining Concession.”

The report advises Conde that he has three options for dealing with Rusal’s position at Friguia – preservation of the concession, revocation, or renegotiation. Whatever option is chosen, the report recommends parliamentary ratification with the aim of nullifying the extra-parliamentary process Conde has used to date. It also puts the fate of Friguia and Rusal directly into the campaign for parliamentary and presidential elections in Guinea, which must be held by next year. “Friguia will be a lightning rod in the elections”, a Guinean opposition figure says.

The text of the Technical Committee’s report, dated June 3, is stamped “Projet” (Draft). A Conakry source claims that since June there has been no change in the committee’s recommendations. “That report, I believe, is final.”

Last week, Rusal announced that a Paris arbitration tribunal has overruled the Guinean Government attempts to nullify the Friguia privatization agreement. Rusal said: “the tribunal held that the Share Purchase Contract of 14 April 2006 between RUSAL and the Republic of Guinea by which the Company purchased shares in Friguia bauxite and alumina complex is valid and rejected certain allegations by the Guinean side to the effect that RUSAL’s purchase of the shares was invalid or improper. The tribunal also ordered the Republic of Guinea to compensate RUSAL EUR250,000 in legal costs. RUSAL believes that the award further demonstrates RUSAL’s reliability as a long-term strategic investor in the Republic of Guinea. The Company is determined to continue its work implementing projects and contributing to social development in the country.”

Because the tribunal proceedings were confidential, the text of the judgement is not available. Guinean sources respond that the government is not bound by the judgement to drop the conditions set by the Technical Committee report. “Even if you admit the privatization was legal,” claims one Conakry source, Rusal “had obligations they have failed to meet.”

Rusal says its legal position to operate both the Friguia concession and the new Dian-Dian concession has been ratified by agreement with President Conde. Rusal reported to shareholders in December 2012 that the signing of an annex to its Dian-Dian agreement should be “subject to…the ratification and promulgation in accordance with the laws of the Republic of Guinea.”

The Technical Committee’s report requires the National Assembly to ratify Rusal’s position, not the National Transition Council appointed by Conde last year.

Analysis and redrafting of Guinean mining law and regulations, and the legal advice which Conde and the Technical Committee have been following, come from Soros and a team of American lawyers he has retained, sources in Conakry say. The Technical Committee refers to the Soros role when it reports: “As part of this mission, CTRTCM is assisted by a consortium of law firms. These firms have carried out an audit of mining projects and handed the CTRTCM a series of reports on their findings and recommendations.”

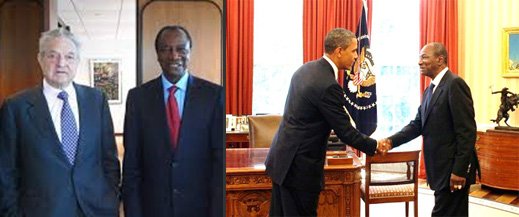

Soros has also advised Conde on other mine concessions in Guinea. According to one high-level Guinean source, Conde has promised access to mineral assets and mining concessions to “hands friendly to Soros”. Soros, the Guinean official claims, has helped arrange contact between Conde and US President Barack Obama; from that a US Justice Department and FBI investigation then followed of the Simandou iron-ore concession held by the Israeli, Beny Steinmetz, and his Brazilian partner, Vale.

Early this year Soros reportedly urged Conde to stop his personal negotiations with Steinmetz. Instead he advised Conde to support the Technical Committee’s recommendation to withdraw the Simandou-1 and Simandou-2 assets which Steinmetz had taken over from Rio Tinto after the latter was found by the previous Guinean government to have violated its concession terms. Soros has now set his sights on Deripaska and Rusal, according to Guinean sources.

A London commodity trader, who has been close to the Guinean bauxite and alumina trade in the past, claims that Wilde and the Gerald group are competing for Conde’s favour against Mercuria, the expanding Swiss commodities firm controlled by Marco Dunand and Daniel Jaeggi. The London source believes the Gerald group has an interest in what the new Ukrainian government may decide to do with Rusal’s control of the Nikolaev refinery. Mercuria, he says, is only interested in taking Guinean bauxite and alumina for sale in international markets. A spokesman for Mercuria in Geneva, who declined to give his name, also refused to say what interest Mercuria may have in Guinean bauxite or alumina.

London and Conakry sources say the new Friguia plan is similar to one which Reuben and his Trans-World group proposed in Guinea almost twenty years ago, in the late 1990s. Then Reuben, Wilde and their associates offered to finance the Friguia mine and refinery, which had originally been a French project until Pechiney and other French interests dropped out in 1998; that left Guinean managers in control of operations, but without working capital or trading experience. The Reuben-Wilde plan offered both in return for the offtake to trade internationally, and also through the Nikolaev refinery to fuel Reuben’s Russian smelters. At the time Reuben considered Deripaska to be his employee.

That Friguia plan was arranged, the sources claim, by Karim Karjian. Karjian subsequently sued Rusal for welching on its part in his Guinean dealmaking. The UK High Court judgement of 2003 went in Karjian’s favour, and against Rusal. It can be read here.

A Guinean source claims he is “not sure” if Wilde and the Gerald group’s new plan for Friguia “would try to cut off Nikolaev. They don’t need it.” The London source concurs. The conflict between Ukraine and Russia is so intense, and the future so uncertain, he adds, “noone wants to get into a pissing war [over Nikolaev]. They [Gerald] are content to wait.” But between the Gerald group and Deripaska’s Rusal, the sources say there is a long history of commercial competition and personal animosity. “There is no love lost” — taking Friguia over would be “payback for Deripaska”.

Soros has been advising Conde directly and personally on how to redistribute Guinea’s mining concessions. The legal team assisting the Technical Committee may be funded through the Soros family’s Open Society Foundations, which are based in New York. The foundations have an active programme in Guinea, according to their website, aimed at new parliamentary and presidential elections.

“Though blessed with vast quantities of natural mineral wealth, including diamonds, gold, and some of the largest reserves of bauxite in the world” — one of the foundation papers reported in April of this year — “Guinea suffers from endemic corruption, political instability, and deep social fissures.” The Soros remedies include “situational analysis (in the form of op-eds, policy briefs, and reports) [to] discuss what is at stake, including the weakness of the Electoral Commission and the legal and institutional shortcomings, and possible solutions to these challenges.” The foundation recommends a role in Guinea’s future for “development partners such as the European Union, UNDP, France, and the United States” — none for Russia.

The foundation spokesman Laura Silber (right) was asked to say how this effort in Guinea has been organized and paid for. “Do Mr Soros, members of your [Open Society Foundations] Board, your organization’s executives, and/or lawyers associated with the foregoing play an advisory or expert role in the ongoing CTRTCM recommendations for government action in relation to the Friguia concessions?” Silber and two of her associates, Mailynn Miller and Kritika Bansal, agreed to accept the emailed question, but they refuse to answer.

The foundation spokesman Laura Silber (right) was asked to say how this effort in Guinea has been organized and paid for. “Do Mr Soros, members of your [Open Society Foundations] Board, your organization’s executives, and/or lawyers associated with the foregoing play an advisory or expert role in the ongoing CTRTCM recommendations for government action in relation to the Friguia concessions?” Silber and two of her associates, Mailynn Miller and Kritika Bansal, agreed to accept the emailed question, but they refuse to answer.

Soros’s investment interests in mining and commodity trading are held in part by Soros Fund Management, whose office is a city block away from his foundation office in Manhattan. Required disclosure of the Fund’s shareholdings reveals current stakes in several international mining operations, including gold, silver, uranium, and rare earth metals. Silber was asked whether there is a conflict of interest between the foundation-funded advisory work in Guinea and Soros’s financial interests. “Have the associates, experts, lawyer advisors or others working on Guinea matters with Mr Soros and the Open Society Foundations,” Silber was asked, “reviewed the shareholdings and investments of Soros Fund Management in mining companies for the possibility of conflict of interest?” Silber will not answer.

Leave a Reply