By John Helmer, Moscow

Oleg Deripaska, control shareholder of Rusal, the Russian state aluminium monopoly, is the leading investor of Russian funds in offshore businesses which have failed. He is also Russia’s largest corporate debtor. Noone else in the circle of President Vladimir Putin has performed so improvidently and unpatriotically.

When the costs are counted of last month’s Nigerian High Court ruling against Rusal’s ownership of the Aluminium Smelter Company of Nigeria (Alscon), and the ruling expected from the same court in Abuja next week, Rusal is facing a liability and compensation judgement amounting to $2.8 billion. That’s one-third of Rusal’s annual sales revenues; it’s also one-third of Rusal’s gross debt, and almost half its current market capitalization on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Not a single metals analyst or investment banker in Moscow dares to acknowledge the case, or analyse the risk now facing Rusal from the Nigerian courts and its government.

On November 10 the High Court at Uyo ruled that Rusal has lost its 85% shareholding of Alscon through a subsidiary, Dayson Holdings, and must obey the order of the Supreme Court, Nigeria’s highest court, cancelling the privatization of the smelter company in Rusal’s favour. “From where I stand/sit,” ruled Judge Ijeoma Ojukwu, “the judgement of the Supreme Court is clear and unequivocal and leaves no room for speculation”. Read the full judgement here.

Judge Ojukwu added that the Supreme Court order had “tied the hands of this court”, and she dismissed the Rusal attempt to overturn the earlier decision.

Left, the Alscon plant at Ikot Abbasi, now closed; right, BFE headquarters in Abuja. A Nigerian press investigation by Bassey Udo of the privatization scheme appeared in June 2015. It was titled: “Inside the huge scam leading to sale of Nigeria’s aluminium plant, ALSCON, to Russia’s RUSAL.”

The Supreme Court had required the Nigerian government’s privatization authority, the Bureau of Public Enterprises (BPE), to restore a 2004 decision and contract awarding the state’s control shares in the plant to Bancorp Financial Investment Group Divino Corporation (BFIG), a Nigerian-American group based in Los Angeles, for the price of $410 million. This was the high bid at the time. For details of how the award was reversed by BPE, and Rusal took control of Alscon paying substantially less, see the story archive.

BFIG applied to the US courts to stop Rusal’s takeover, arguing the Nigerian courts were corrupt and witnesses in danger of intimidation. The US Court of Appeal decided the Nigerian courts were fit to adjudicate the case on condition Rusal agreed to submit to Nigerian jurisdiction. The US ruling of November 2008 started the case between Rusal and BFIG in the Nigerian courts. When Rusal lost, it tried to counter the Nigerian courts by going to an arbitration court in London.

Last month’s judgement in the Nigerian High Court  puts an end to Rusal’s claims to hang on to the smelter, according to BFIG’s general counsel, Jimmie Williams (right). “Now everybody sees the writing on the wall.” He and Nigerian sources do not believe that Rusal’s lawyers will attempt to appeal again to the Supreme Court.

puts an end to Rusal’s claims to hang on to the smelter, according to BFIG’s general counsel, Jimmie Williams (right). “Now everybody sees the writing on the wall.” He and Nigerian sources do not believe that Rusal’s lawyers will attempt to appeal again to the Supreme Court.

Weeks earlier, the Nigerian House of Representatives interviewed former executives of the smelter, asking them whether they favoured Rusal or BFIG to reopen and operate Alscon. There was opposition to Rusal, but no objection to BFIG. The parliamentary committee then recommended to the government and to President Muhammadu Buhari that BPE be ordered to hand the plant over to BFIG, according to the court orders. BPE was told that parliamentary approval of its next operating budget depended on its compliance.

The Russians have continued to resist. As the latest defeat for Rusal was issued in the High Court, a delegation of Russian government officials met their Nigerian counterparts in Abuja, the Nigerian capital, for the fourth in the annual rounds of the joint commission of the two governments on economic cooperation. The Russian co-chairman was Agriculture Minister Alexander Tkachev. The Nigerian press reported his delegation “comprised Russian Ambassador to Nigeria Nikolai Udovichenko, Deputy Minister of Agriculture Mr Evgeny Gromyko and officials of Russian’s firm-United Company Rusal.”

After their talks concluded, the Moscow version of the communique from Tkachev reported “special attention was paid to the situation around the Alscon aluminum plant belonging [sic] to the largest Russian operator and investor in Nigeria – United Company Rusal. The Minister said that a speedy solution to the problems of legal uncertainty around the smelter and its power supply will open the door to restarting production at the plant. Alscon representing the aluminium industry in Nigeria could be an important growth engine of the national economy.” In Abuja, the Russian Embassy’s version of the communique was shorter and less committed to Rusal. “Special attention was drawn to the measures for providing resumption of aluminum production at the Alscon plant owned by the Russian company Rusal.”

Tkachev, a three-term governor of the Krasnodar region, became agriculture minister in April 2015.

Left: Tkachev with Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo, November 11, 2016; source -- http://von.gov.ng/nigeria-russia-collaborate-agriculture/

Right: Members of the Russian delegation with Tkachev, from left: Alexei Arnautov, Rusal director of new projects; Maxim Markovich, Deputy Director of the International Cooperation Department at the Ministry of Agriculture; Deputy Agriculture Minister Evgeny Gromyko; source: https://www.facebook.com/194957124027389/photos/pcb.571853149671116/571852949671136/?type=3&theater

Why has Rusal, which stopped production and shuttered Alscon in 2013, dismissing all but a handful of the plant’s 2,500 employees, continued to claim full control and refused to comply with the Nigerian courts? Corruption is the answer Nigerian sources give.

A US Embassy cable of August 2004, released by Wikileaks, reported the original privatization scheme reflected a “lack of transparency in the bidding process, and perhaps some corruption as well.” Since then Nigerian sources claim Rusal’s tough line was reinforced by Nigerian officials who were, allegedly, hidden beneficiaries of shares in the plant. If Rusal is evicted and BFIG takes over, they stand to lose their interest, the sources speculate, and whatever dividends the revival of the smelter may pay in the future.

Since 2004 there have been four Nigerian presidential administrations, the most recent commencing with General Buhari’s election on April 1, 2015. In February of this year, Buhari (below, left) announced a purge of 26 government agencies, including the BPE. Although no corruption charges have been filed against BPE or its officers, the current BPE head, Vincent Akpotaire (right), is still an acting appointee, on probation.

Other local sources claim that although Rusal does not want to restart the plant, it is using the protracted litigation as a demonstration to the government of neighbouring Guinea, where Rusal’s interests in bauxite mines and alumina refining are more valuable, and more crucial to the company’s need to import bauxite and alumina for the operation of its Russian smelters. For the Guinea story, read this.

Rusal’s website says the company “owns 85% stake in Alscon, which produces aluminium from alumina supplied by Rusal Friguia refinery in Guinea that is perfectly located to ensure fast and effective delivery of raw materials to the smelter”. In reality, according to Rusal’s annual reports, both the Nigerian smelter and the Guinean refinery had their output slashed in 2010 and 2011, and both were closed by 2013. “The mothballing of production,” Rusal reported for Alscon in 2014, “was a result of the curtailment program for inefficient capacity.” The shutdown at Friguia, also intended by Rusal, started in April 2012 “as a result of a strike held by court to be illegal”.

Rusal insiders observe that “Oleg Vladimirovich [Deripaska] isn’t just a poor loser. He refuses to lose. That’s despite being forced out of his aluminium assets in Romania, Tajikistan, Montenegro, and Ukraine too.” For details of this Deripaska record, click for Romania; Tajikistan; Montenegro; and Ukraine.

In Los Angeles, Williams said he expects BFIG to win its parallel High Court action, which charges Rusal with failing to meet its investment and production obligations, thereby damaging the plant, cooking the books, allowing equipment to be looted, and depriving BFIG of the profits it would have earned, had its Alscon purchase contract been honoured. “In 2004,” William said, “the plant was valued between $1.2 billion and $1.3 billion. By 2012-2013, expert audits showed its value was less than $90 million. We are suing for $2.8 billion in damages and losses.” For background on the audits of asset-stripping, loan-sharking, and tolling fraud at Alscon, read this.

The High Court in Abuja is expected to announce its judgement on the $2.8 billion claim next week. The latest Rusal report on Alscon, published on August 9, issued this disclaimer: “In January 2013, the Company received a writ of summons and statement of claim filed in the High Court of Justice of the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria (Abuja) by plaintiff BFIG Group Divino Corporation (“BFIG”) against certain subsidiaries of the Company. It is a claim for damages arising out of the defendants’ alleged tortious interference in the bid process for the sale of the Nigerian government’s majority stake in the Aluminium Smelter Company of Nigeria (“ALSCON”) and alleged loss of BFIG’s earnings resulting from its failed bid for the said stake in ALSCON. BFIG seeks compensatory damages in the amount of USD2.8 billion. In January 2014 the court granted the Company’s motion to join the Federal Republic of Nigeria and Attorney General of Nigeria to the case as co-defendants. The next hearing is currently scheduled for 27 September 2016. Based on a preliminary assessment of the claim, the Company does not expect the case to have any material adverse effect on the Group’s financial position or its operation as a whole.”

Nigerian sources say the disclaimer, which Rusal contingency notes to financial reports have repeated since 2013, reflected confidence on the part of Deripaska and his head of foreign operations, Sergei Chestnoy (right), an expert on corruption, in the backing for Rusal from President Jonathan and BPE director-general Benjamin Dikki. BFIG officials and Nigerian sources say General Buhari’s defeat of Jonathan in 2015 and his dismissal of Dikki at BPE this year have made a big difference to Rusal’s position in Nigeria. “They should be showing this as a new contingency in their financial reports,” Williams noted.

notes to financial reports have repeated since 2013, reflected confidence on the part of Deripaska and his head of foreign operations, Sergei Chestnoy (right), an expert on corruption, in the backing for Rusal from President Jonathan and BPE director-general Benjamin Dikki. BFIG officials and Nigerian sources say General Buhari’s defeat of Jonathan in 2015 and his dismissal of Dikki at BPE this year have made a big difference to Rusal’s position in Nigeria. “They should be showing this as a new contingency in their financial reports,” Williams noted.

Rusal’s annual reports indicate that design production capacity of the Alscon smelter was 197,000 tonnes of aluminium per annum. In 2010, production was 18,000 tonnes; in 2011, 15,000 tonnes; in 2012, 22,000 tonnes; and in 2013, 2,000 tonnes. Two years ago, in October 2014, Rusal claimed it “has put great efforts into turning the smelter, which had previously sat idle for 10, years into a modern, technologically advanced manufacturing enterprise…we are making every effort to ensure that Alscon will be ready to recommence production once the aluminium market improves.”

While Alscon remains shuttered, Nigeria is obliged to import more than a billion dollars’ worth of aluminium products from foreign sources. The plan for Alscon had been for it to make the country self-sufficient and to export aluminium to the rest of Africa.

Moscow bank analysts who focus on the base metals and follow Rusal refuse to respond to questions about Rusal’s liability in Nigeria. According to Williams, Rusal may be hoping that if it loses next week’s High Court judgement, it may be able to walk away without paying anything. “We don’t agree,” Williams said. “We are looking for more than that. There has to be a fair compensation proposal on the table.”

When BFIG and BPE agree on the takeover, Williams added, there must also be a recalculation of the price BFIG should pay. “Our original offer was $410 million. But if the plant is only worth $80 million to $90 million – a fraction of what it was worth in 2004 – then what we should pay should be less.”

Williams also noted that the electricity grid which supplied the smelter, and which had been financed by the Nigerian government, has also been damaged. Until it is repaired, the smelter cannot be revived. “Until there is finality for our lawsuit against Rusal,” Williams again, “there can be no finality on the numbers [for restarting aluminium production in Nigeria].”

In Moscow, inside Rusal there is no interest in reviving aluminium production in Nigeria, and considerable reluctance to commit to the investment and production targets previously set by the Guinean government for bauxite mining and alumina refining in that country. Instead, company sources say Deripaska has concentrated on reorganizing Rusal’s domestic production with the only ready source of cash he can lay his hands on – the Russian state budget. This means state orders for aluminium to equip bridges, railcars, power lines, wiring for municipal construction. The story of Deripaska’s lobbying to use state regulation to boost the domestic demand for aluminium cans for beer instead of plastic bottles, can be read here.

Last week, Roman Andryushin (right), Rusal’s marketing director,  said the company’s strategy for future sales growth is a combination of increased production of all types of aluminium products in the domestic, Russian market, and growth of exports to Europe. “Rusal sees itself as a global player and is positioned as one of the main sources of new technologies for the production of aluminium and alloys, especially of complicated preparation and composition; for example containing scandium. Such alloys provide manufactured products with improved performance properties.”

said the company’s strategy for future sales growth is a combination of increased production of all types of aluminium products in the domestic, Russian market, and growth of exports to Europe. “Rusal sees itself as a global player and is positioned as one of the main sources of new technologies for the production of aluminium and alloys, especially of complicated preparation and composition; for example containing scandium. Such alloys provide manufactured products with improved performance properties.”

“Rusal is a national manufacturer, so it considers its priority is the market of Russia and CIS countries. Of course, the contraction of demand in the domestic market hits hard the Russian manufacturers of aluminium products, and to the greatest extent, producers of aluminium profiles and cables. But thanks to the active position of Rusal, and it is a huge project of work with market participants, with the Ministry of Industry and Trade of Russia and other agencies, [we] have managed not only to mitigate the fall in consumption, but even to increase the supply of aluminium in the domestic and foreign markets…. We forecast that by the end of this year our sales of aluminium to the market of Russia and CIS countries will rise by 5% to 800 thousand tons, of which 50% will be in the segment of alloys with exceptional characteristics. My personal dream and the dream of my team is to sell 1 million tonnes of aluminium products in the Russian market in 2018. And we know how to achieve it.”

At the present level of output, Rusal is producing and selling between 20% and 25% domestically. At Andryushin’s 1- million-tonne mark, domestic sales would amount to almost a third of Rusal’s production. Not since Deripaska abandoned the Russian market for a strategy of exporting primary aluminium to China and Japan, has there been such a shift inside the company. The impact in the stock markets has yet to show.

On the Hong Kong and Moscow exchanges, where limited trading of Rusal shares takes place, the rise in the global price of aluminium has helped lift Rusal’s share price, along with almost all its international peers.

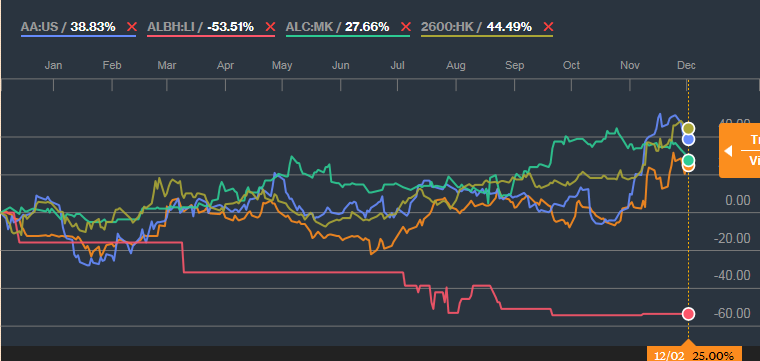

ONE-YEAR SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY FOR RUSAL AND GLOBAL ALUMINIUM PEERS

KEY: yellow=Rusal, +25%; blue=Alcoa (US), +39%; green=Aluminium Corp of China (Chalco), +45%; grey=Aluminium Company of Malaysia, +28%; pink=Aluminium Bahrain, -54%. Current market capitalization: Rusal, $6.6 billion; Alcoa, $12.7 billion; Chalco, $6.6 billion; Aluminium Co of Malaysia, $28 million; Aluminium Bahrain, $753 million.

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/486:HK

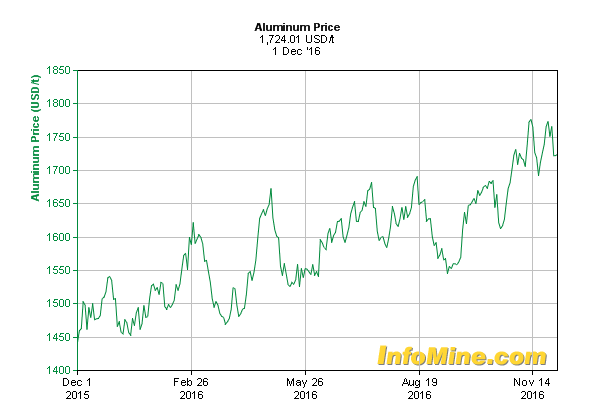

ONE YEAR PRICE TRAJECTORY FOR ALUMINIUM

USD per metric tonne

Source: http://www.infomine.com/investment/metal-prices/aluminum/1-year/

Leave a Reply