By John Helmer, Moscow

Flinders Mines (FMS) is what one investor calls a hedge fund hotel, a hangout for bettors on a sure thing.

The source means that after Victor Rashnikov (front seat, left), owner of Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Combine (MMK), decided to buy FMS last November, roughly half the value of the company was bought by hedge funds aiming to collect on the difference between what they advanced and the takeover price they were certain the big Russian would end up paying at deal closure. Because of the action by the Chelyabinsk Arbitrazh Court on March 30, and in the days that have followed, that bet now threatens to lose the hedge funds A$255 million.

The angry punters are threatening to retaliate in an Australian court by taking hostage with their own injunction Rashnikov’s separate stake in another Australian iron-ore miner, Fortescue Metals (FMG). That 4.99% shareholding is currently worth A$909 million. There are plenty of Australian lawyers ready to sell their services to take a crack at that jackpot. Then there are the bribe artists, I mean public relations consultants offering to stimulate an Australian media frenzy towards Russia; that’s another sure bet.

More than sure bets on big money are at stake here. The action by high Russian officials to have Rashnikov abort his takeover bid, and concentrate MMK’s resources on developing Russian iron-ore resources, creates unusual speculation on Russian acquisitions offshore in future. But even more – the freedom of Russian capital, make that oligarch capital, to move where it chooses, and into whatever assets it selects, from sports concessions to banks and mines, may now be in doubt.

Along has come Dmitry Afanasiev (front seat, right), a Moscow lawyer with an American education, a Florida house, and a client base that started with and still includes Oleg Deripaska. A director on the board of Rusal, Afanasiev has survived the many firings of lawyers which occur when Deripaska loses litigations. Afanasiev was first hired because he succeeded in representing the Zhivilo brothers in a claim against Deripaska for stealing their Novokuznetsk aluminium smelter and its metal trading contracts. Deripaska ended up paying the Zhivilos, then in protective asylum in France, more than $60 million. Afanasiev switched sides.

Afanasiev’s associates are talkative about his special skills, the ones he employed, for example, as an advisor to the federal government when Deripaska was running into defence ministry opposition to his selling the Samara Metallurgical Plant to Alcoa of the US in 2004. In that and other cases since, Afanasiev has proven to be a mediator between government officials and corporate executives; a lobbyist in short, and something of an expert on the peculiarities of Russian deal-making. He has also branched out into sensitive and lucrative government work, like the occasion he offered to help the South African government persuade the Russian government to support its bid for a seat on the UN Security Council.

As Afanasiev assured this legal publication profile, not everyone in Russia is a crook.

Afanasiev is a principal in the firm known as Egorov, Puginsky, Afanasiev and Partners. At first, the firm refused to say whether it has been engaged to act for the MMK defence unless the names of the lawyers listed in filings to the Chelyabinsk Arbitrazh Court were identified. When the firm was asked to confirm that Afanasiev himself is involved, his spokesman asked for time to consult her boss. She then responded: “we can not comment yet. If the information will appear, we will inform [you].”

MMK has been asked to confirm whether Afanasiev is on their case. The response reported by an investment bank source is that “people are trying to figure out who are MMK’s and Flinders’ legal advisers; however, it will not be possible to find out anything this way as both signed confidentiality agreements with the advisers.”

That the names of lawyers acting for the parties are so sensitive, MMK has asked the law firms and the court to keep them secret is no sign, to use Afanasiev’s language, that they are crooked, or that the legal process isn’t a genuine one. Rather, the secretiveness is a sign that Rashnikov, his chief executive Boris Dubrovsky (front seat, centre) and their Australian friends think their best chance to remove the Chelyabinsk court injunction and carry out their takeover deal is to lobby the Kremlin to change its mind, and signal the judge in the case, Natalia Bulavintseva, accordingly.

According to Gary Sutherland, chief executive of FMS, his firm will not release “non-public” materials. But Sutherland won’t explain why he and Rashnikov have chosen to designate the conventional and the obvious as non-public and non-releasable. “Flinders,” according to an email from Sutherland, “will not be releasing non-public information about its appeal because it may prejudice Flinders’ ability to conduct its case, and also be in breach of ASX [Australian Stock Exchange] Listing Rules requirements. If you are unable to get public information from the public record, that is a matter for you to take up with the relevant body. Regarding Flinders’ Russian legal advisors, again, I can only repeat my response: if it is on the public record then please get it from there, otherwise it will only be released if required as part of Flinders’ continuous disclosure under the ASX Listing Rules. I trust that brings an end to the matter.”

Sutherland is the signatory on his company’s statement to the Australian Stock Exchange, dated April 16, which claims: “MMK and Flinders have separately received their own legal advice in relation to the injunction proceedings and both MMK and Flinders consider the proceedings are without merit. MMK has filed an appeal against the injunction with the Appellate Court. Separately and on its own independent legal advice, Flinders has commenced its own appeal against the injunction with the Appellate Court in Russia.

As part of its ongoing efforts to ensure a successful outcome to the Scheme process, Flinders notes it has engaged Russian legal counsel who are advising Flinders on their options with respect to the court process. The appeal court will likely set a time for hearing the appeals by the end of April 2012 with a best estimate that the matter will be heard and a judgment delivered before the end date under the SIA of no later than 21 July 2012.”

Officials at the Chelyabinsk Arbitrazh Court say no appeal documents have been filed by or on behalf of FMS. At the Court of Appeals №18, which is also situated in Chelyabinsk, a source said that if the FMS appeal against the injunction exists, it must go first for consideration by the Chelyabinsk Court, where Judge Bulavintseva is hearing the case, and where the deal stop was ordered. If the appeal were received, the source said, then information about it should appear on the case file on the court website on the same day or the next. Time’s up – the FMS appeal hasn’t been registered.

So Sutherland was asked to explain what his market announcement means “if there has been no court filing, and if in your April 16 statement you meant to persuade the market that there was?” He was also asked to clarify why engagement of the Afanasiev law firm “should not be disclosed to the market because they are not instructed to file in the Chelyabinsk court but have different instructions?” He refuses to reply.

When house lawyers for MMK have been asked by lawyers acting for hedge fund stakeholders and investment bankers for details of their court filings, their response, and non-response, have been identical to Sutherland’s email. One investment bank source describes the tone of the responses as “hostile”.

Who is covering up what and for whom? If hiring a lawyer were a genuine sign that MMK and FMS believe that their principal obstacle to closing the deal is in the regional arbitrazh court, it’s difficult to see why releasing the names of the lawyers on the caption of the court papers should be kept secret. It’s just as difficult to comprehend why they should also keep secret their arguments, factual and legal, before the court.

On November 1, FMS was priced at 16 cents a share, pretty much unchanged since September 2009, with a market capitalization of A$291 million. Late in November, after MMK offered to buy the mining company for 30 cents a share — A$546.3 million for the lot — the share rose in market trading until it reached MMK’s bid level in January. In the interval of several weeks, hedge funds around the world started buying, the latecomers paying 27 or 28 cents, in order to turn a profit of 2 or 3 cents, when the deal was done.

Only now the deal has been stopped dead in its tracks in Russia, leaving mid-level MMK executives in the process of renting Australian accommodation, arranging new management and corporate structures to accommodate the new asset, making all sorts of promises to their brand-new Australian friends.

Some of the hedge funds have called up their lawyers to ask what they can do to compel MMK to complete the deal, or punish it and compensate them, if MMK won’t or can’t buy FSB as promised.

The specific performance clause in the MMK takeover deal which the hedge funds would like to enforce in a damages claim in an Australian court is at Section 4 of the deal contract, the Scheme of Arrangement, which can be found at page 62 of the circular to shareholders issued on February 27, 2012:

“4. Representations and warranties MMK represents and warrants that:

4.1 it is a corporation validly existing under the laws of its place of incorporation;

4.2 it has the corporate power to enter into and perform its obligations under this deed and to carry out the transactions contemplated by this deed;

4.3 it has taken all necessary corporate action to authorise the entry into this deed and has taken or will take all necessary corporate action to authorise the performance of this deed and to carry out the transactions contemplated by this deed.”

Note the wording, “corporate power” and “corporate action” in these points. MMK isn’t saying it has complied with all applicable Russian laws and regulations, nor does it disclose or imply that Rashnikov sought and received from Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and his government the necessary permission to do this deal.

The provisions in this contract also allow that if MMK’s undertakings to the deal violate Russian law, regulation, or public policy, the entire scheme is dead.

“7.9 If the whole or any part of a provision of this deed poll is void, unenforceable or illegal in a jurisdiction it is severed for that jurisdiction. The remainder of this deed has full force and effect and the validity or enforceability of that provision in any other jurisdiction is not affected. This clause 7.9 has no effect if the severance alters the basic nature of this deed or is contrary to public policy.” Since MMK and FMS have accepted that the law of South Australia should govern their agreement on a “non-exclusive” basis, the question remains – if the Kremlin has informed Rashnikov that his deal is contrary to the public policy of Russia, and that he must bring himself and his company into Russian compliance, what can the law and judges of South Australia say about it? In a conflict of laws situation, so long as Judge Bulavintseva says no dice, no deal, what remedy remains for the bettors of Zurich, London, or New York?

By the way, MMK has its own domestic iron-ore mine currently in planning. Called Prioskol, and located in the west Russian region of Belgorod, MMK’s last annual report claims its reserves exceed 2 billion tonnes. That is more than double the Pilbara deposit which Flinders Mines proposes to start mining by 2014.

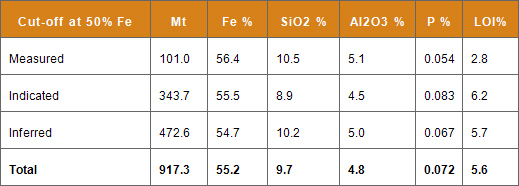

FLINDERS MINE RELEASE — MINERAL RESOURCES

Source: Flinders Announcement on 14 November 2011.

Today MMK isn’t saying how much it has already spent or is budgeting to spend on Prioskol; nor will it confirm what the iron grade is at Prioskol. Four years ago, in 2008, it released to the industry press this claim: “MMK has started the implementation of the project on the development of the Prioskolsk iron ore deposit with the reserves of 45 million tonnes of rich ore and over 2 billion tonnes of ferruginous quartzite. Prioskolsk GOK is to reach its projected capacity by 2017. The deposit’s reserves are sufficient to satisfy the needs of MMK in iron ore in full for over 60 years. Its favourable geographical location and larges reserves allow considering the deposit’s use in MMK’s overseas projects as well.”

That year too, MMK was reported as telling the local wire service Interfax that it was planning to spend $1.8 billion on bringing Prioskol into production. The annual report for 2008, released in March of 2009, claimed that “securing 100% of its requirement for quality iron ore with its own captive supplies is a strategic task for MMK. The share of the Company-produced iron ore materials in the 2008 total iron ore supplies was 20%. In the future MMK intends to have the share of its captive iron ore materials raised through the expansion of productive capacity at the Bakal Mining Administration Co., Chelyabinsk Region, and the Podotvalnoye and Maly Kuibas iron ore deposits near Magnitogorsk. Due to the global economic recession the Prioskolsky Iron Ore Deposit Development Project has been temporarily suspended.”

Prioskol isn’t mentioned again in the annual report for 2009.

In October 2010, MMK told the London Stock Exchange it had contracted with Hatch Engineering “to identify a most efficient method of Prioskolskoye field development.” At that time, according to MMK, it was planning to build an ore-enrichment plant with “planned capacity of up to 25 mtpy will cover MMK’s needs in iron-ore raw materials for 60 years and more.”

Why one year later Rashnikov decided to opt for the Australian mine project, and why he is refusing to confirm his current plan for Prioskol, are matters he’s been discussing with Afanasiev to put on the Kremlin table, if Afansiev gets that far.

Leave a Reply