By John Helmer in Moscow

One of the lucrative carry trades is about to be chopped.

A new report by the UK market regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA), has warned that it intends to crack down on links between companies preparing share market sales and financial media reporters and columnists, the effect of which, according to the FSA, has been to unlawfully hype share price and make money on the sly. In short, market abuse by insiders and their media accomplices.

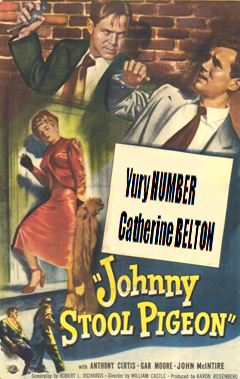

The natural targets are claims like these, which Bloomberg has made its standard form of reporting attribution, especially in relation to the stock price of United Company Rusal, with which reporter Yury Humber is especially familiar. The first time this source appeared, it was reported by Bloomberg as “someone familiar with the matter.” The number of “people familiar with the matter” grows in inverse proportion to the unlikelihood of the information, or the reluctance of Bloomberg to identify the source as an inside one.

In December, when Rusal was still struggling to win approval of its listing prospectus by the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, Bloomberg reported the approval had already been granted “according to two people, who declined to be identified”. Next, when Bloomberg reported that Rusal had achieved a share price fixing of up to HK$12.50 for the initial public offering, the sources were “two people familiar with information.” A month later, to convince the market the Rusal stock was in genuine demand in the market, Humber found the stock was already “fully subscribed”. His sources were “two people familiar with the matter”. They requested anonymity, according to Humber, “because the discussions with investors are private.”

What is private, according to the Bloomberg bible, may now be prosecuted as market abuse, according to the FSA. The FSA’s market abuse directive first originated as a directive of the European Union in 2003. The EU directive was subsequently adopted by the UK in 2005.

Investigation of UK financial media for market abuse is new, though, and the FSA concedes revolutionary, for it potentially strikes at the lucrative promotional businesses of London’s financial public relations firms, and the law firms which are also associated with share listings and market manipulation.

Technically, the FSA acknowledges, PR agents and lawyers may not belong to regulated firms, and may thus not come under the FSA’s remit. Neither do newspapers. “We can’t compel them”, an FSA source says, “but what they do may come under the market abuse directive.”

The Telegraph describes the FSA move as “a crackdown” on the media, and a move with “stifling” effect on the free investigative press. Only, as has now become clear to the FSA and market readers, Bloomberg, FT, and other financial media have abandoned their investigative role in favour of public relations. The Telegraph reports this as a violation of “tradition”: “The regulator’s orders threaten to cut off the traditional flow of information between journalists and the City that allows the media to explain and scrutinise goings on in the financial world”

|

For a second shot at the meaning of that word “scrutinise”, here’s the full FSA report. |

“Leaks ahead of announcements threaten market integrity,” the FSA reports, defining “strategic leaks” as those communications to reporters which are “designed to be advantageous to a party to a transaction…[they] are particularly damaging to market confidence and do not serve shareholders’ or investors’ wider [sic] interests. It is therefore in all interests to ensure that senior management of all organisations who handle inside information establish (and are seen to establish) a much stricter culture that firmly and actively discourages leaks.”

For the first time since the Moscow newspaper known as The Exile went out of business, the open-line telephone has been used an investigative tool. According to the FSA, “our enquiries revealed that media reports containing leaks were often closely preceded by telephone conversations between insiders occupying senior roles on a corporate transaction, and the journalists who published those media reports. Due to their position as insiders, these senior individuals held detailed knowledge of the transaction. The calls between the insiders and journalists lasted up to 20 minutes in length and in some cases took place with journalists the afternoon or evening before the leak was first published.”

Catherine Belton of the Financial Times has been a conduit for share price hype for a variety of Russian oligarchs in the past, although she now says that she had a falling-out with Oleg Deripaska and Vera Kurochkina of Rusal, shortly before Rusal listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange last January.

| Regarding the newest of the oligarchs to make its pitch through the FT, Belton and her colleagues reported last week that “Severstal, the Russian steel company, is preparing to list its gold division in London this year in a deal expected to value the business at about $4bn, several people close to the company have confirmed. Severstal – majority owned by Alexei Mordashov, a close ally of Vladimir Putin, Russia’s prime minister – plans to retain a stake of 65-70 per cent in the new company.” |  |

Watch carefully as “several people close to the company” turn out to claim sovereign guarantees for their valuations on account of the factoid that the selling shareholder is “a close ally of Vladimir Putin”. Normal reporting practice would oblige the ace reporters of the FT to confirm the alliance with Putin.

But he isn’t likely to. The last close friend of Putin’s, who was adopted from the Tatler to the Telegraph, was Sergei Pugachev. According to the Telegraph, Viscount Linley, the cabinet-maker and interior decorator, was also convinced at the time he “sold a stake in his business earlier this year to Sergei Pugachev, a billionaire friend of Vladimir Putin known as ‘the cashier to the Kremlin’”. There’s been no update in the London financial or social sheets on how it has happened that Pugachev is currently losing every asset he has owned in Russia in an out-of-court bankruptcy procedure. From that his erstwhile friend hasn’t helped to extricate him, and the cash he once had (from the Central Bank) is now demanded for repayment.

Meanwhile, back at the FT’s hype of Mordashov’s IPO value, “one banker involved in the transaction said the valuation was likely to hit $4bn or possibly $5bn as details about the assets and the company’s growth plans were disclosed to the market.” The details the FT is proposing to its readers to know about in advance cannot be the troubles Severstal Gold is facing with the Government of Guinea over title to the LEFA goldmine there; nor can they be the story of over-valuation of the Russian gold assets once owned by Arlan and Celtic Resources. For analysis of “details” that may push share prices downward, theFT reporters would have to pick up their telephones to other people familiar with the situation.

The problem which the FSA has surfaced – for the very first time in the history of stock market regulation in the City of London – is that the only people so familiar with the situation who find their way into print, are those with a payoff interest in lifting the share price.

| There are subtle differences between the rules applying to pre-listing publicity; secondary listings involving companies which are already listed on the London Stock Exchange; and dealings in shares and information of companies already trading under FSA supervision. But the scope for application of the FSA market abuse directive is wide – and this time it’s open season on the stool pigeons of the press. |  |

So the next time you read a London financial sheet mentioning a “person familiar with the matter”, be a scout for the FSA, on the lookout for evidence that should trigger a new leak review according to these FSA guidelines:

| • media articles or other published documents containing accurate non-public information; • contact by journalists which may indicate a potential leak; • market rumours heard by the firm indicating a potential leak; • large unexplained movements in the price or increased volumes of the issuer’s securities (or the offeror or offeree’s securities in a takeover); • rule 2 announcements prompted because the offeree company was subject to accurate rumour, speculation, reporting or a movement in its share price; and • if firms or the issuer in receipt of inside information, would gain a strategic benefit from leaking. |

Leave a Reply