By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

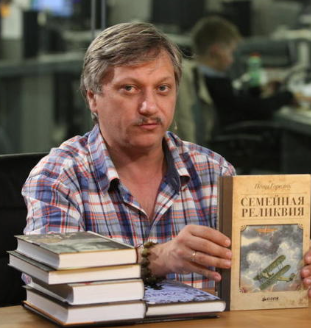

Repeating lies over and over makes old-fashioned Joseph Goebbels-type propaganda. Repeating lies, then contradicting them; moving them from one government-paid think-tank to another; footnoting a new lie to an older version; quoting policemen and gangsters saying fatuities; adding slang and the words of pop songs—this is still Goebbels-type but stretched out and product-diversified to make its author more money. This is Mark Galeotti’s (lead image) method.

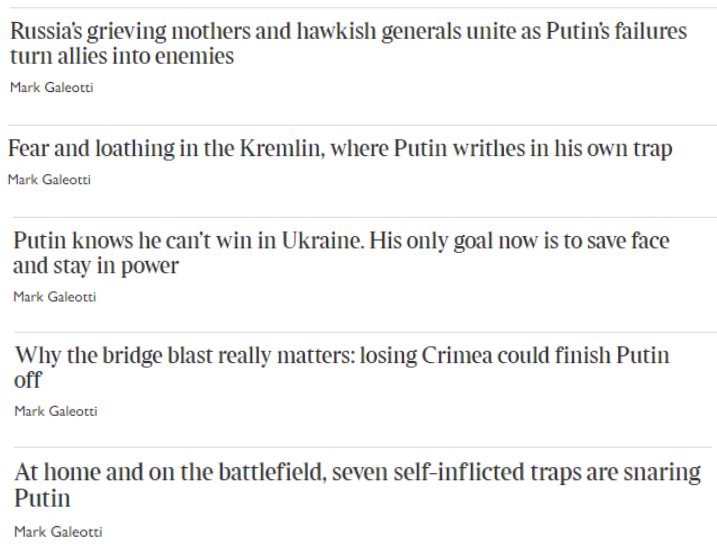

In the history of Russia-hating war propaganda projected from London, down the street and across the river from the present office of Elizabeth Truss, there is the headquarters of the Rupert Murdoch method. He has engaged Galeotti to be the new Russia expert of The Sunday Times in the confidence no one will question how the expert knows what he says, and whether it’s true or false. The Murdoch method is to convince his audience to pay money for the sensation of the suspension of disbelief. At least between Friday nights and Monday mornings.

For several weeks in a row the Sunday Times has published these Galeotti headliners.

Reading them in retrospect doesn’t stretch their use-by date. Three years ago this investigation of Galeotti’s method was published to explain why. Here it is again.

His new book on the business of Russian crime isn’t about business at all. There’s not a single item from a balance-sheet, cashflow analysis, asset trace, or financial indictment in Galeotti’s effort to exaggerate Russian criminals to mean Russian people, all of them.

The Russians are also the unique criminals of our world, he thinks – no other nation on earth matches them for their criminality. So for the protection of the rest of the innocent world, and to protect the uncriminalized from being Russianized, the Russian state, that’s the “super-mafia” of Galeotti’s targeting, should be destroyed by warfare. And since Galeotti repeats the slang of the Russian streets himself to rub in his conclusion that “mainstream society” – that’s everybody –“ reflect[s] a fundamental process of criminalisation of politics and daily life”, he means that Russians deserve more than their mouths washed out. Galeotti is a mercenary; his book a weapon — a stun-gun for the naive, an improvised explosive device for the unguarded, a neutron bomb for the sceptical. Means, motive, opportunity for a hate crime in the service of a war crime.

Galeotti’s book, The Vory, Russia’s Super-Mafia, was published by Yale University Press a year ago; its paperback edition was released this year. Galeotti and his book are promoted in Moscow in English by The Moscow Times, the Dutch Government-financed publication.

Galeotti’s paperback edition runs to 272 print pages, to which he’s added footnotes, bibliography, and index. Two-thirds of the way through, at page 180, Galeotti admits that all of the criminal gangs and organizations he’s been trying to describe since page one have ceased to exist. The Georgians, for example, were fighting among themselves “as a desperate and brutal last gasp before the ‘highlanders’ [Chechens, Georgians, Armenians, Azeris] too are assimilated into the multi-ethnic, multi-commodity , crime-business-politics of the modern Eurasian underworld.”

But what is this new thing? Galeotti attempts several definitions at page 185, but can’t make his own evidence fit. So he decides “Russian organised crime is used”, principally because Russian is the spoken language, and also because the criminals and their groups “broadly share the same cultural and operational characteristics while also having some direct relationship with Russian itself.”

Galeotti’s new definition doesn’t identify any “operational” or “direct” relationship. This is because he knows nothing himself, and has no source for the financial operations of anybody he now reclassifies in his “Russian gang” targets.

The only evidence he presents for the new target is from three sources – the first, a Russian student Galeotti calls Kolya whom he interviewed in London 1996 (while Galeotti was under cover at the Foreign Office). Kolya is quoted as saying: “Who are they? The [Russian] mafia is like the government, except that it works. Seriously, the mafia is, well, whatever it wants to be.”

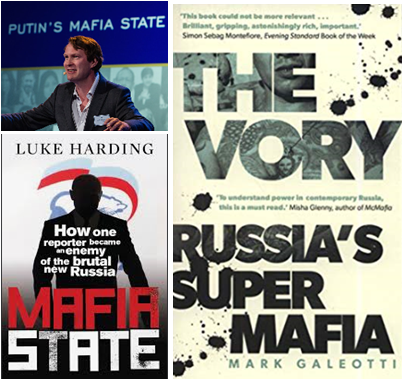

At this stage, two-thirds of his book having already been despatched to the Yale University printing press, Galeotti offers two more sources for his new type of “Russian organised crime”. One of them, with whom Galeotti says he had a conversation in Kiev in 2016, is reported as an “officer from the SBU, Ukraine’s security service.” The other is Luke Harding, a London reporter and fabricator of anti-Russian materials. From Harding’s hearsay Galeotti borrowed the sub-title of his book, “Russia’s Super-Mafia”. Galeotti’s rhetorical trick is to claim that on Harding’s page, “this is a neat phrase that obscures more than it explains”; only to use the phrase himself repeatedly and without any qualification.

For evidence of Harding’s record, read this.

Then all of a sudden, on page 195, Galeotti announced: “there is no doubt that Russian and Russian-linked organised crime can be found across the globe.” Look at the carefully worded phrase – “Russian and Russia-linked organised crime”. This turns out to be a statement about Russia, with an innuendo about “organised crime” and its “link” to Russia that is undemonstrated, unevidenced.

Watch Galeotti’s next move as he attempts to conclude: “It [sic] is defrauding millions out of the US Medicare and Medicaid programmes, swapping heroin for cocaine with Latin American drug gangs, laundering money around the Mediterranean, selling guns in Africa, trafficking women into the Middle East and raw materials into East Asia, and buying up real estate in Australia”.

There is no footnote, no source, no evidence to which Galeotti’s depiction of this grandiose, global Russian racket can be sheeted. How can it, if Galeotti does not distinguish between capital flow sources and capital destination havens; between Delaware, British Virgin Islands and Cyprus; between US, British, French and Russian arms sales to African and other states; between the sale of sex and the export of oil and gas; between Chinese buyers of Australian real estate and everyone else.

The long history of US criminalization of opium, marijuana, heroin and cocaine, and of the ethnic groups targeted by those laws – Mexicans and Chinese in California, Jews and blacks in New York – is a subject altogether unknown to Galeotti; the only American criminals he knows are Russian-speakers in Brooklyn. For the alternative history of ethnic hate crime dressed up as America’s Public Enemy No. 1, read this.

Of several hundred footnoted references for Galeotti’s claims about Russian criminality, he has managed to identify only a handful of Russian sources. Counting each live one whom Galeotti claims to have interviewed himself rather than to have read or heard about, there are thirteen. The first, “Lev Yurist”, is characterized as “a relatively low-level gangster”; he’s the source of 20-year old information about his initiation into “the criminal fraternity”. Another is “a retired police officer I spoke to” who was Galeotti’s source for the tattoo codes of gangs in Yekaterinburg in the 1950s. A “hanger-on” Galeotti reports as having attended a meeting of gangsters in Moscow in 1994 is the source for the remark, “Moscow is not Sicily”. In the book he was followed by “one middle-ranking Moscow mobster I spoke to”; he is the source for saying “in the early years we fought because we had to…but by [1996-7] we could settle down and become businessmen rather than generals.” Galeotti’s footnote reveals that this information was noted down by Galeotti in 2011 – that’s ten years after the event, and almost as long before he sent it to Yale University Press for printing.

Galeotti uses source anonymity to conceal how few gangsters or policemen he actually recorded and quoted. In what they said, they are uniformly obsolete, imprecise, irrelevant to the case Galeotti is trying to make. “We just had to be cooler, smarter and everything would be fine” is one gangster’s recollection, footnoted in Galeotti’s record in Moscow in 2010. “A former Russian police investigator” told him in 2016: “our criminals are now so much more like yours.”

Galeotti managed to get no Georgian, Jewish, Armenian, Azeri, Tajik, or Uzbeki gangster to speak to him. He claims to have spoken to one Chechen, a sixty-year old claiming to have retired from professional hit-jobbing. He was quoted as saying: “the Russians taught me to want to kill, and then they taught me how to do it well”. A Moscow police officer was then reported by Galeotti as his source for the Chechen’s job reference: “He’s serious, a very serious man.”

About the four most notorious Chechen assassinations in recent Moscow history – Paul Tatum (right) in 1996; Paul Klebnikov in 2004; Anna Politkovskaya in 2006; and Boris Nemtsov in 2015 – Galeotti has nothing to report; he and his 13 sources know nothing. The sources who know have not spoken to Galeotti, and he won’t admit it.

The only Federal Security Service (FSB) source Galeotti claims to have spoken to was reported as a serving colonel. His only quoted remark: “Putin was sent by God to save Russia”. Galeotti also claims this source invited Galeotti to his palatial home outside Moscow, where Galeotti spotted a Range Rover, BMW and Renault in the garage. Galeotti reported: “I have no doubts at all that he is as corrupt as they come.”

The only Jewish Russian Galeotti encountered, Lev Chernoy, is recorded as commenting in the year 2000 on the dress code of Russians according to “the laws of initial capital acquisition, applicable everywhere.” But Chernoy didn’t say that to Galeotti; he cribbed it from another reporter. If Lev and his more important brother Mikhail Chernoy (Cherney) are known to Galeotti for their roles in the Russian non-ferrous metals business in the 1990s, Galeotti doesn’t let on; for the Chernoy file, start here. Aluminium is not mentioned in the book. Galeotti has heard, he writes in passing, of conflicts over copper and steel smelters in the Urals, involving the Uralmash and other groups. But he is ignorant of the business histories of Mikhail Chernoy, Iskander Makhmudov, Vladimir Lisin, and Dmitry Pumpyansky, the men who took control of copper, steel, and steel pipemaking.

Galeotti tries other rhetorical devices to conceal his lack of evidence. On almost every page he uses Russian street slang or gangster argot to make his own familiarity with his subject appear more genuine than it is. In a glossary of terms at the back, there are 53 such terms; Galeotti’s use of them is smoke he is blowing in the eyes of his readers.

Another trick is to footnote a claim in the text for which Galeotti’s only evidence is a reference to himself in one of his own publications; there are 22 of those in the bibliography, ten times more than any other author on the list. Unless the reader is able to go back to the original Galeotti source, and trace that to find its origin in credible, primary evidence, this scheme of self-reference is retrospective faking.

“I became one of the first Western scholars to raise the alarm about the rise and consequences of Russian organised crime”, Galeotti big-noted himself at the start of his book. At that point, he claimed to be asking “the real question, with which this book ends, is not so much how far the state has managed to tame the gangsters, but how far the values and practices of the vory have come to shape modern Russia.” The rhetorical question turns out to be an innuendo Galeotti runs on every page until the end, as he leaves no question-marks at all. The accession of Crimea in 2014, and the ongoing war in the Donbass, according to Galeotti, are “criminal wars”: “when Russia invaded Ukraine [sic], it did so not only with its infamous ‘little green men’ – special forces without insignia – but also with criminals. To the gangsters, this was not about geopolitics…it was about business opportunities.”

His conclusion is that “two processes have taken place… the nationalisation of the underworld… [and] the gangsterisation of the formal sectors” – in short, everything Russian is criminal. This is a hate crime. But Galeotti protects himself from the charge by the tactic of contradicting himself. At page 208, thirteen pages on from having “no doubt”, Galeotti cites a US state attorney’s report issued in New York in 2013 for this remark from Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov: “There is no organised crime in Russia. None…they are hooligans, there are some lightweight bandits, there are drunks who come together to get up to something. But organised, concrete crime nowadays does not exist.”

Galeotti then mixes his claims, turning political and oligarchical operations into “symbiosis” with his gangsters. Evidence? State Department cables leaked by Wikileaks. A veritable Protocols of the Elders of Foggy Bottom.

Aside from the three Russian oligarchs who have operated abroad against Putin, whom Galeotti names in order to endorse — Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Boris Berezovsky, and Vladimir Gusinsky – and whose criminal indictments and convictions he ignores, he fails to mention a single Russian oligarch: not one of those identified in the US Treasury list nor in the current US sanctions nor at the Kremlin’s Christmas dinner table.

Over twenty years no photographs have been published of Galeotti with any notable Russian businessman, politician, or public figure in Russia or elsewhere. By contrast, he has appeared with Mikhail Khodorkovsky (left), speaking together at a Cambridge University conference, April 29, 2019. Right: the only notable Russian whom Galeotti has been photographed with is at the Moscow cemetery grave of Vyacheslav Ivankov, the gangster known as Yaponchik who was assassinated in Moscow in July 2009. Galeotti reports the details of the assassination incorrectly, a Chechen operation by no one Galeotti knows. Ivankov had finished lunch and was stepping down the front steps of the Bely Slon restaurant, surrounded by several bodyguards. They protected their man’s head and chest, but left his lower body exposed. The strike wasn’t fatal, and Yaponchik survived in nearby Botkin hospital for almost three months, before succumbing to secondary infection. I know because I saw the attack from my office window, which was above the assassin’s panel van parked at the curb.

He also fails to report on a single state enterprise in oil, gas, nuclear energy, banking, ports, railways, aerospace, diamonds, titanium, arms, or on one of its executive officers. That’s most of the Russian economy unacknowledged and ignored — even more of its official GDP. Organized doubtless, but uncriminalized so far as Galeotti and his sources know from their evidence. Except that’s not what Galeotti claims by the innuendo of national guilt by association.

If there’s a “symbiosis”, Galeotti’s omission is so large as to be a gaping hole – he knows nothing about Russian business. He can’t even get Gusinsky’s first name correct, calling him Mikhail instead of Vladimir. But he claims to know enough to conclude from a Spanish official’s allegation, based on information purchased from the late Alexander Litvinenko, that “the FSB is absorbing the Russian mafia”.

Galeotti’s only discussion of Russian business is one-hand, second-hand from William Browder’s case; that’s to say, Browder’s case against Russia, not the Russian case against Browder; Galeotti accepts the former without questioning and without citing any evidence except for Browder’s book. To balance the evidence against the lies, and judge the truth for yourself, try these two investigative reporters on Browder – Lucy Komisar and J’AccuseNews; the latter also provides an extensive bibliography for investigations throughout Europe on Browder’s criminal operations.

Who is Galeotti, author of such claims as cannot meet simple admissibility tests in an international court of law? In print at least, Galeotti is not so sure himself. English born, but with an Italian origin that has turned, he says, into more fluent Italian than he claims his Russian to be, Galeotti is an uncommon Italian name, most of whose bearers come from the northern province of Perugia. That’s a region whose only claim to mafia fame is that it was the site of the prison assassination of a Sicilian mafioso, Angelo La Barbera. Galeotti appears not to be kin, but there may well be, as he says himself, a “symbiosis”.

Left: the street in Gubbio named Via Galeotti is named after Gino Galeotti. Born in Gubbio in 1867 he became a famous Italian doctor and pathologist, who worked on vaccinations for the plague in India, infectious diseases in China, and psychopathological ailments affecting Italian soldiers and airmen during World War I. He died in 1921. For more, read this. Right: Renzo Galeotti, Mark Galeotti’s father, was born in Carrara, northwest of Gubbio, in 1949. An artist, he now lives and works in England. Among his works is a series of paintings dedicated to the Italian communist intellectual, Antonio Gramsci. A report of Renzo Galeotti’s contacts with Italian and British communists record that his son Mark was exposed as a child to contact with James Klugmann, the official historian of the British Communist Party and one of the recruiters of Kim Philby and other well-known Cambridge spies.

Although intentionally vague – Galeotti conceals his family and his dates in the Wikipedia profile – he has reported in a UK company registration that he was born in October 1965.

In a Prague résumé he says he graduated from Cambridge University (Robinson College) in 1987, and had a year’s gap claiming to be “political liaison” at the insurance group, Lloyds. He then went to the London School of Economics between 1988 and 1991, graduating with a PhD. Its topic, he says, was “The Impact of Afghan War on the USSR, accepted without revisions”. The book of that work was not published until 1995, several years after he claims to have finished it.

There is an interval until 1996-97 when Galeotti reports a secondment as a “research fellow” at the Foreign Office. During that time he says he was also employed as a senior lecturer in history at Keele University, 1991-2008; Keele is a provincial college rating on the British university ladder at No. 48 and falling.

Galeotti published almost nothing in the first half of the 1990s. British sources believe the gap is indicative of official government work, classified; Galeotti’s family associations with well-known communists and Soviet-era spies may have required lengthy vetting of his loyalties. After Keele, Galeotti took a post at New York University; it’s unclear whether that was full or part-time. Since he left, his academic posts in Europe appear to have lasted no more than a year or two.

Galeotti also lists his employment at think-tanks, all of them paid for by NATO member governments. In 2016 one was the European Council on Foreign Relations; follow its money trail, including George Soros’s Open Society Foundation and Rockefeller Brothers Fund, here.

Galeotti says one of his current paymasters is the Institute of International Relations in Prague, most of whose money comes from the Czech Foreign Ministry, Polish state sources, the European Commission, and German foundations. The other paymaster is the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI) in London; it calls itself “an independent think tank” and a charity which “rejects funding that is incompatible with its independence or honesty”. Galeotti’s RUSI stipend is collected from several NATO governments, the British Army and Defence Ministry, even the British Embassy in Moscow.

Galeotti also claims to be selling research through two commercial entities. One of them, Mayak Intelligence, has one staff member and one shareholder – that’s Galeotti — and a primitive website. Its corporate registration is brand-new; in July he registered the company at the address of his father Renzo at 12 Hurley House, Broom Road, Teddington, Middlesex, TW11 9NS.

Another of junior Galeotti’s employers in the consulting business is Wikistrat. This was created by Israelis, and is now headquartered in Washington where its paying clients include many of the US armed services and intelligence agencies, as well as the British Air Force, and US weapons exporters.

Galeotti also says he was engaged at MGIMO, the Russian State Institute of International Relations, which because of its ties to the Foreign Ministry and foreign policy-making groups in Moscow is a regular target for MI6 and the CIA. Galeotti says that in April 2014 he presented “Transnational Organised Crime: MA course for MGIMO- University, Moscow. Then he claims: “2014 – 2016: MGIMO (Moscow): Confronting Transnational Crime.” MGIMO officials decline to corroborate Galeotti’s lectures at the institute, or identify who authorized Galeotti’s employment at MGIMO. In the only review to be published in Russian of the new book, Oleg Fochkin (right), a specialist in covering Russian criminality, condemned Galeotti for ignoring Russian research and having “no credibility”.

Fochkin’s books on Russian crime can be found here. He says Galeotti cribbed his story from western sources for western readers who know too little to realize Galeotti’s mistakes. His source interviews are “not legitimate…no bandit respecting himself, no cop or petty swindler will ever tell the truth to a foreigner. But particularly for money, to relieve the foreigner of his bucks, that’s almost a sacred duty. And so [Galeotti] listened open-mouthed and believed that everything he was told about the thieves’ world was the truth.”

Galeotti’s NYU résumé makes this claim: “He is a specialist in transnational organized crime, security affairs and modern Russia. He started his academic career concentrating on conventional security issues, including the impact of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the implications of the disintegration of the USSR. However, in his fieldwork he encountered the rising new generation of gangsters carving out their portions of the decaying Soviet Union and was one of the first Western academics to recognize this as an emerging security concern.”

A US expert on Russia is disbelieving. “He staked out turf that made him a sort of ‘reasonable’ ‘moderate’ within the Russia Panic Industry. I don’t find him particularly illuminating.”

The list of Galeotti’s endorsers, printed at the front of his new book, are from the ranks of the anti-Russian establishment working on US, NATO, and UK Government stipends, including the Integrity Initiative, a Foreign Office and MI6 disinformation operation targeted at Russia. The claque includes Peter Pomerantsev, Oliver Bullough, Edward Lucas, Michael Weiss, Charles Clover, Owen Matthews, and a former President of Estonia by the name of Toomas Ilves.

Left: Mark Galeotti. Right, clockwise: Peter Pomerantsev; Oliver Bullough; Owen Matthews; Edward Lucas. In the first leaks of the classified British papers of the Integrity Initiative operation, Pomerantsev and Lucas were listed operatives.

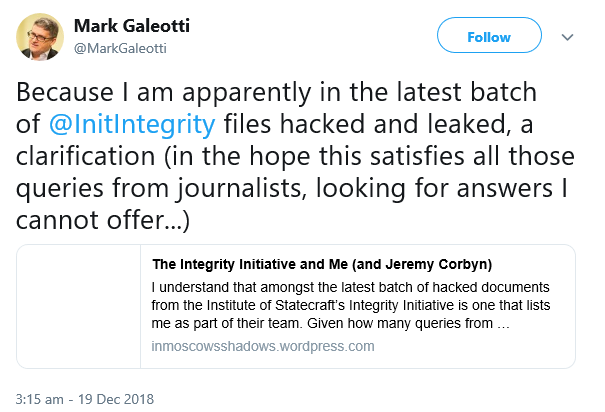

Galeotti was one of the listed operatives in the Integrity Initiative (II) documents released in December 2018. Entitled “The Institute for Statecraft Expert Team: Roles and Relevant Experience”, the document reported Galeotti as one of its selected experts: “Specialist in Russian strategic thinking; the application of Russian disinformation and hybrid warfare; the use of organised crime as a weapon of hybrid warfare. Educational and mentoring skills, including in a US and E European environment, and the corporate world.”

In that context, Galeotti’s publications have been analysed as fabrication and propaganda contracted and paid for by the British government and allied agencies.

Galeotti responded in a blog post and tweet admitting he had been approached by the II organizers. “I said that I’d be glad to be involved in some way if the project got off the ground, depending on quite how it evolved. And that was it. I never heard any more, so I don’t know if the bid was successful or not. I have no other relationship with the II or the Institute of Statecraft.”

Source: https://twitter.com/

Galeotti denies receiving either II money or the benefits of organizational involvement. He did not mention that confirmed II operatives have been boosting his book. He also defends the operation and its British government financing. “Nor does FCO [Foreign & Commonwealth Office] funding demonstrate any kind of nefarious intent. The FCO funds all kinds of projects, some smart and some stupid, some political and some purely cultural. Given that there can be no doubt that there is a Russian political-information campaign being waged, through open media and covert influence, it is right and proper that measures are taken to understand and respond.”

The most detailed analysis of the Foreign Office, MI6 and British Army operations which have interacted with II is “Briefing note on the Integrity Initiative” by British academics Paul McKeigue, David Miller, Jake Mason, Piers Robinson.

Left to right: Paul McKeigue, University of Edinburgh Medical School; Piers Robinson, Professor of Journalism, Sheffield University.

They published their report on December 21, 2018. This indicates that Galeotti has been financing himself in parallel with the II networks, receiving money directly from the same or parallel sources rather than through II applications. Promotion of his books, though, comes from the II networks.

Common money-pot; different hustle; same con.

Leave a Reply