By John Helmer, Moscow

Oleg Deripaska has launched an attack on Leonid Mikhelson, GennadyTimchenko and Kirill Shamalov in an oligarch showdown which President Vladimir Putin must decide, because Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev cannot. Not since 2008, when Deripaska appealed to Putin for support of his attempt to take Norilsk Nickel away from Vladimir Potanin, has there been a multimillion dollar contest like this, inside the Kremlin wall. Deripaska’s move also comes after two years of attempts by the US Government to force regime change in Moscow by attacking Putin, his family and his “cronies”.

At stake is whether Russian beer-drinkers should be allowed to drink their brew from large plastic bottles, which are fabricated from polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the polymer manufactured by Sibur petrochemical and plastics company. Until mid-December 2015, Sibur’s shareholders were Mikhelson (below, left) with 50.2%; Shamalov (centre) with 21.3%; Timchenko (right), with 15.3%, and Sibur management (13.2%). The troika all sit on the Sibur board of directors; Mikhelson is chairman.

The Chinese petrochemical company Sinopec bought 10% of Sibur’s shares in mid-December, for $1.34 billion. It has the option to buy another 10% by the end of 2018, and it has already taken a seat on the Sibur board. It isn’t clear how the Chinese stake has redistributed the troika’s shareholdings, especially that of Timchenko, who is under US and European sanctions.

Shamalov, a lawyer, came to Sibur from Sibur’s former parent, Gazprom, the Gazporom pension fund and Gazprombank. He is also one of Putin’s sons-in-law.

State visit to Sibur’s Voronezhsintezkauchuk plant, May 23, 2013: 1st left, Mikhelson; 2nd left, Putin; far right, Shamalov.

To the Sibur troika, the fight is worth a fraction of $318 million, versus a fraction of $220 million to Deripaska. The fraction depends on what proportion of PET bottles and what proportion of aluminium cans are filled with beverages other than beer. It also depends on how much Deripaska is calculating he can seize from the others in the beverage container market – maybe $100 million, maybe more.

Three weeks ago, Deripaska’s spokesman announced that drinking beer from Sibur bottles “is not correlated with the civilized beer production”. The Russian Brewers Union has responded with a letter to Deripaska, and to Putin, declaring: “Dear Oleg Vladimirovich [Deripaska], we know how great is your influence in the government and among the [State Duma] deputies, thanks to the great contribution that you make to the economy. We ask you not to use this influence to destroy the beer industry, it will bring you little or no additional benefit; it will cause huge damage to the country.”

The brewers’ letter was issued on April 13. To Deripaska, the brewers asked: “What is the impact of the plastic ban worth fighting for? Demand for aluminum cans will grow by several percent; the demand for beer will generally fall by 20 to 30 percent. You will receive an additional sales volume of several thousand tonnes of aluminum, and we will close several plants; the regions will lose 40 billion rubles in taxes; tens of thousands of people will lose their jobs; alcoholism will increase. Are the few thousand tonnes of aluminium worth all of this?”

A ban on PET bottling for beer has been lobbied for more than five years. When first reported here, the money at stake was estimated at $1.5 billion; that was the value of Russia’s PET (polyethylene terephthalate) packaging market, about one-third of which was reportedly filled by beer. The Russian beer market, in 2010 figures, was worth about $6.6 billion, so the plastic bottled segment of the market was worth $2.2 billion, including the value of the beer.

Back in 2011, when the ban was first proposed in Moscow, no government official was eager to admit he was supporting it. Also, there were three ministry-level objections – Industry, Economic Development and the Federal Antimonopoly Service. State Duma deputy Viktor Zvagelsky (right) who was promoting legislative enactment of the ban, was accused of being an agent of the vodka distillers trying to reduce the flow of cheap beer to low-income drinkers, and divert them towards cheap vodka under glass.

Back in 2011, when the ban was first proposed in Moscow, no government official was eager to admit he was supporting it. Also, there were three ministry-level objections – Industry, Economic Development and the Federal Antimonopoly Service. State Duma deputy Viktor Zvagelsky (right) who was promoting legislative enactment of the ban, was accused of being an agent of the vodka distillers trying to reduce the flow of cheap beer to low-income drinkers, and divert them towards cheap vodka under glass.

At the time Rashid Nureyev, then spokesman for Sibur, said the government should not be trying to act against the global trend toward more, not less PET bottling. “To our knowledge, there is no a prohibition on the use of PET bottles for beer and non-alcoholic products anywhere in Europe. Sibur hopes that consideration of the regulations on prohibition of the use of plastic packaging in the beer industry will be objectively reviewed and finally rejected by the Customs Union. It is in no way justified.”

Sibur got its way until the campaign resumed in 2014, this time with a bill from Mikhail Tarasenko of the Duma Committee on Labour and Social Welfare. He claimed he was against guzzling among the young. The brewers were already agreeable not to put beer in PET bottles of more than 2.5 litres. Tarasenko proposed lowering the limit to bottles of 1.5 litres, then 0.5 litres with less than 4% alcohol content.

“If you have a mini brewery, you cannot just take the bottle and start pouring beer”, an industry source explains. “You need to buy a bottling line. The cost of bottling lines depends on their capacity. Typically, the amount is measured in thousand bottles per hour. For example, a line capacity of 24,000 bottles per hour costs €5 million. Some companies simply cannot afford it. Once a company has set up for itself a line of bottling of glass bottles or aluminum cans, the company must purchase bottles or cans from those who produce them. At the same time, we have regions where there are simply no plants that produce glassware. Breweries in Kamchatka and Sakhalin will close, because they will have nothing more to work with. To transport glass containers is impossible.”

Last week, on April 28, the brewers held a press conference in Moscow. They argued that if the PET ban is implemented, the big international beer companies will profit at the expense of the Russian brewers. According to Vladimir Antonov (below, left), First Vice President of the Ochakovo brewing company, “it will be necessary to replace the current volumes of manufacture of beer in PET packaging with an alternative. But today the glass container market does not have sufficient capacity to provide the necessary number of bottles for the brewers, who will run short. In addition, the plants will need to purchase new, foreign equipment for bottling in new packaging. This is a large financial cost the brewing industry simply cannot afford.”

Vyacheslav Mamontov (above, right), Executive Director of the brewers union, said the PET ban will be no deterrent. “In the PET packaging,the biggest of 2.5 litres, there are only 125 grams of alcohol. In a half-litre bottle of vodka, there are 200 grams of alcohol. The cost of one gram of alcohol in the PET-bottled beer is almost 1.5 times more than one gram of alcohol in vodka.”

The press conference publicly revealed detail about what had been happening behind closed doors in meetings with Prime Minister Medvedev. There had been no collective presentation by the can manufacturers, one of the speakers said. “Deripaska personally stood before Mededev and said that the industry has evolved, that we have to solve the PET problem, and follow with adoption of the law. The largest source of raw materials [PET] is the Sibur company, whose shareholders are Timchenko, Shamalov. They are sensible people who can adequately convey their position to the Government – maybe even better than Deripaska.” Mamontov added: “We’re trying to bring it to the partners.”

Deripaska is the force for the ban in the Duma, Mamontov believes. “We have to rely on the fact that all the stakeholders should make an informed decision.” For the full press conference, watch this.

Industry reports suggest that up to 45% of the volume of beer sold in Russia is packaged in bulk plastic bottles. Glass bottles and aluminum cans account for 25%; kegs of beers, another 5%. There are also estimates that about 24% of the Russian beer market is sold in PET bottles of 1.5 litres.

Sibur is not eager to join the public debate.

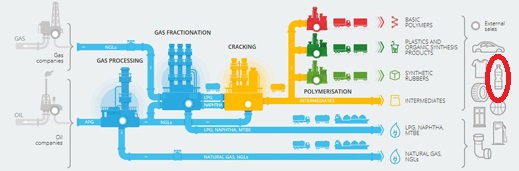

PET BOTTLES IN SIBUR’S CHAIN OF PRODUCTION

Source: http://www.sibur.ru/en/

Sibur’s latest annual report discloses that its overall sales revenue jumped 5.2% to Rb380 billion ($6.2 billion); earnings, up 32% to Rb135.6 billion ($2.2 billion).

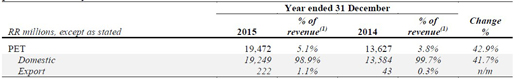

The company says that 17% of its total sales revenue for the year came from the plastics division. In 2015, PET sales were booming. Sales volume grew by 6.7% to 298,571 tonnes, but sales revenues jumped by 42.9% to Rb19.5 billion ($318 million). – page 39-40.

SIBUR’S PET SALES FOR 2014, 2015

Source: http://investors.sibur.com/~/media/Files/S/Sibur-IR/Financial-results/MDA_FY%202015.pdf

The PET container division was worth 11% of the sales result of the plastics division; but that is just 5.1% of the company’s aggregate sales. Still, its accelerated growth last year meant that PET bottling was worth slightly more to the plastics division than in the previous year, while in 2014 PET container sales revenue amounted to noticeably less, 3.8% of the company-wide sales figure. “Our effective average selling price largely reflected negative dynamics in the international market prices in US dollar terms, which was strongly compensated by Russian rouble depreciation. The increase in sales volumes on a 6.7% growth in production volumes was largely attributable to substantial sales of inventories that we accumulated during 2014 in line with the production expansion. The increase in production was a result of PET capacity expansion at our production site in Blagoveshchensk (increase in annual nameplate production capacity to 210,000 tonnes from 140,700 tonnes) and low base of 2014 due to lengthy shutdowns related to the capacity expansion. In 2015, domestic sales accounted for 98.9% of total PET revenue, while 1.1% was attributable to export sales.” – page 19.

A statement was issued by the company several weeks ago on the impact of the PET ban. “In the event of the introduction of the proposed draft law restrictions on the use of PET containers in the beer industry, our current sales will suffer only slightly due to the high demand from the soft-drinks manufacturers. However, the development potential of an important segment of the domestic petrochemical industry will be exhausted in the long term.”

Rusal’s releases, financial statements and reports conceal much more than Sibur does. Rusal’s last annual report says the company produces “strip for composite panels, strip for soft food cans… DOZAKL purchases most of its raw materials (principally aluminium coil) from the Group’s foil mills and on market. DOZAKL’s main customers are industrial customers located within Russia and the CIS.” DOZAKL, says Rusal, buys the aluminium tape required for can production from Rusal Foil LLC, “at arm’s length prices tied to the price of aluminium on the LME.” DOZAKL is the acronym for the Dmitrov Can Tape Test Plant.

In 2014 the value of the aluminium tape or strip, which Rusal sold DOZAKL, was just $11.3 million, according to the Rusal annual report for the year. There is still no comparable report for 2015. DOZAKL is owned by Deripaska’s EN+ holding. Because it’s a downstream aluminium producer, Rusal doesn’t include its results in its reports. EN+ conceals the tonnage and value of DOZAKL’s production.

DOZAKL produces aluminium cans for soft food. Beverage cans, including beer cans, are different. They are not produced in Deripaska’s factories, but he supplies the metal for them, but it is uncivilized to calculate how lucrative that line of business is — Rusal doesn’t reveal what the value is of the aluminium ingot or sheet it supplies the beverage can-makers in Russia. Of those there are just two – Rexam and Can-Pack. See for more details.

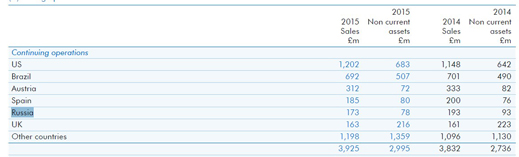

Rexam, a London-based, UK-listed company, produces cans at plants in Naro-Fomisk, near Moscow; St. Petersburg, and Argayash, in the Urals. It supplies cans to the brewers, especially the internationals selling beer in Russia (Carlsberg, ABInBev, SAB Miller), and reports that in 2015 “despite weak macro economy, Russia grew 3% benefiting from the can gaining share in the pack mix”. This means that more canned beer was being bought by Russians compared to glass bottled beer and plastic bottled beer. Rexam reveals also that in 2014 its can sales in Russia amounted to £193 million ($318 million). In 2015 this dropped to £173 million ($265 million) – sales volume increased, but because of the collapse of the rouble, the sterling value of the sales declined.

Still, making and selling Russian cans – that’s soft-drink as well as beer cans – was only worth 5% to Rexam on a worldwide basis.

THE VALUE OF RUSSIAN CAN SALES IN REXAM’S GLOBAL CAN REVENUES, 2014-2015

Source: http://www.rexam.com

Rexam doesn’t say how much it pays for the aluminium in its Russian cans. It does say it buys all the aluminium for its Russians cans from Rusal. Rexam reports that the cost of raw materials – that’s mostly aluminium – was £2.2 billion out of a total of £3.5 billion (63%). It also reports that the price it pays for aluminium represents “almost 60% of our annual cost base from continuing operations, some £2bn annually”. Another way of gauging the cost of the aluminium Rexam fabricates into its cans is to compare raw material costs in 2014 and 2015 to sales revenues figures for those years. The percentage comes to 56% and 57%, respectively.

That suggests a cost of the Rusal aluminium in Rexam’s Russian cans of £108 million ($178 million) in 2014; £99 million ($151.5 million) in 2015.

Rexam was obliged to cede about 10% of its Russian market share when Can-Pack, a Polish producer owned by US interests, expanded its production with a plant at Novocherkassk. Can-Pack has continued expanding, and now has three Russian plants. Can-Pack reveals no sales, profit, or market share data for Russia. But if it currently has about 30% of the Russian market, then extrapolating from the Rexam data, it is likely to be paying Rusal between £40 million and £45 million ($61 million-$69 million) per annum.

Together, then, Rusal’s sales to the two can-makers are between $200 million and $220 million per annum.

“Who will win?” Vadim Drobiz asks. He is director of the Centre for Federal and Regional Alcohol Markets (TsIFRRA) in Moscow. “Firstly, beer consumption is not expected to feel any impact. How much beer they will drink will stay the same, no matter whether it comes out of plastic, metal, faceted glass. There is some decline to be anticipated, but it is correlated to other factors. Over the last eight years, this has just been demographics. No effect has been caused by changing the containers or increasing excise tax rates or reducing the number of outlets – only demographics. Fifteen to seventeen percent of the consumers of beer have disappeared over the past eight years. That’s because there are half the number of young people. So who will lose from the ban – only the PET producers. The beer producers won’t lose out. They will equip new bottle lines. Now they are opposed. But in fact, they will instal bottle lines, and produce the same amount of beer.”

“Who will win?” Vadim Drobiz asks. He is director of the Centre for Federal and Regional Alcohol Markets (TsIFRRA) in Moscow. “Firstly, beer consumption is not expected to feel any impact. How much beer they will drink will stay the same, no matter whether it comes out of plastic, metal, faceted glass. There is some decline to be anticipated, but it is correlated to other factors. Over the last eight years, this has just been demographics. No effect has been caused by changing the containers or increasing excise tax rates or reducing the number of outlets – only demographics. Fifteen to seventeen percent of the consumers of beer have disappeared over the past eight years. That’s because there are half the number of young people. So who will lose from the ban – only the PET producers. The beer producers won’t lose out. They will equip new bottle lines. Now they are opposed. But in fact, they will instal bottle lines, and produce the same amount of beer.”

“The economic justification for the PET ban is economic – it supports the glassmakers and aluminium. That’s pure commerce. Maybe it’s justified. But from the consumer’s point of view, it is absolutely not justified.”

Leave a Reply