By John Helmer, Moscow

![]() @bears_with

@bears_with

The semi-annual sale of Russian paintings this week by London’s leading auction houses fell short of proving that demand has overcome five years of wartime pressure and is recovering with the price of crude oil. The Russian art market remains unsettled, however, by the disappearance of big Russian bidders who are now on the run from fraud and bankruptcy charges at home and asset freezes around the world.

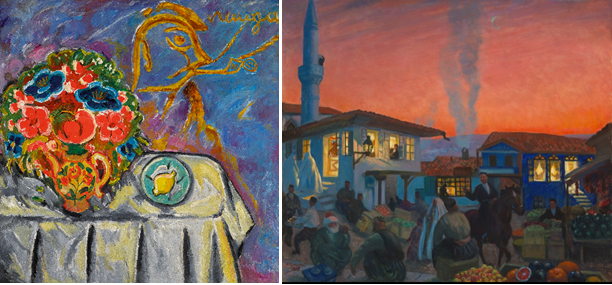

Sotheby’s, which has led the London sale results in the past with a market share of more than a third, reported putting 164 pictures on the block, and realizing £10.4 million in sales. The number of lots dropped 55% from the June auction of 2018; 123 of the lots sold. This is a clearance rate of 75%; a year ago the comparable rate was 73%. The total value is up 14%. The top sellers were Mikhail Larionov’s “Still Life”, painted in Moscow around 1960, which fetched £1.2 million; and a clutch of seascapes by Ivan Aivazovsky, including “Ship at Sunset off Cap Martin” of 1859 for £1.9 million.

MacDougall’s reports total proceeds of £5.3 million, down 20% from its result in June 2018; the house was offering 305 lots (including icons but excluding objets d’art). A view of Crimea did best. This was Boris Kustodiev’s “Bakhchisarai”, painted in 1917 and depicting a Tatar bazaar. It fetched £1.57 million. This may have been a distress asset sale, according to Moscow art reporter Tatiana Markina. She noted “the picture has one drawback — it was already sold five years ago (it went for £1.6 million).”

Left, Mikhail Larionov’s “Still Life”, from about 1960 – sold by Sotheby’s for £1.2 milliion. Right, Boris Kustodiev’s “Bakhchisarai”, 1917 – sold by MacDougall’s for £1.6 million.

For a comparison of the London sales in June 2018, read this.

“Demand is strong and getting stronger,” comments William MacDougall. “Don’t read too much into an individual auction’s results; it depends a lot on the luck of the draw — which works they’re able to acquire. The low point was two to three years ago when oil prices fell below $40; it’s been in recovery since then. Of particular interest this week was the recovery in Russian Contemporary, back above pre-crisis levels with very lively bidding. The broader trend for the market is stable to up.”

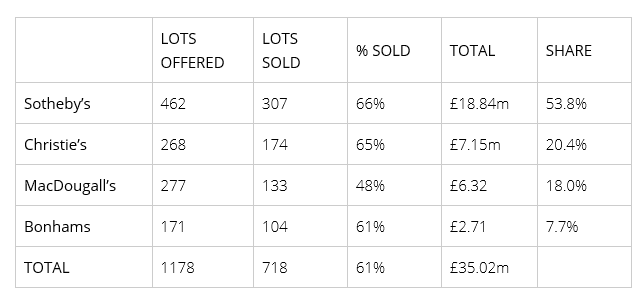

Simon Hewitt, a Geneva-based independent analyst on Russian art, regularly produces tabulations for each semi-annual round of auctions by the leading London houses. These provide the most reliable yardstick for comparing this week’s results to last year’s.

SIMON HEWITT’S SALES TABLES FOR THE LONDON AUCTIONS OF RUSSIAN PAINTINGS — JUNE 2018

Source: https://www.russianartandculture.com/

NOVEMBER 2018

Source: https://www.russianartandculture.com/ For the most comprehensive review of the Russian art market, read Simon Hewitt’s despatches in Russian Art + Culture; click to open his archive.

As the tables show, Bonham’s trails far behind the other houses. This week it managed to sell 90 out of a total of 173 lots; a 52% clearance rate compared to 61% last year. The total sum came to £1.94 million; that’s an improvement of 65% year on year. The big ticket items for Bonham’s were a portrait by Philip Malievin of about 1920 — despite the crude handling it fetched £312,563 – and a pillbox in the shape of a frog from the Fabergé workshop in St. Petersburg before 1899. It sold for £225,063.

Left: Philip Malievin, “Portrait of a young girl in a pink dress”. Right: a jeweled frog from a collection of the Oppenheimer family of South Africa.

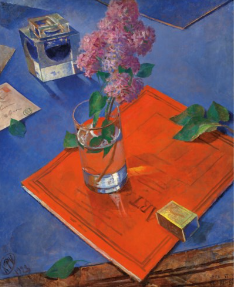

The result at Christie’s this week is exceptional, but interpretations differ. Altogether, 387 lots were up for sale; the clearance rate was 67% — down slightly from a year ago. But Christies’ total came to £16.2 million — a blow-out resulting from the sale of Lot 84, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin’s “Still Life with Lilac” (lead image), which went for £9.3 million. Subtract that from Christies’ proceeds leaves £6.9 million; this figure represents no change from a year ago.

“Still Life with Lilac” was painted by Petrov-Vodkin in 1928; the new sale price is almost three times the previous record for a work by the artist. It had been given to an Italian art critic and collector who exhibited it from time to time in Italy before he died in 1965. The painting was displayed in Moscow last month, but the sale may not return it to Russia. This depends on the identity of the buyer.

Sources in the auction room say that at one point there were seven people bidding on the telephone. The opening bid from one of them was £2 million; the auction house estimate in the catalogue was between £1 million and £1.5 million. Another source claims Christie’s had been “very confident before the sale, expecting it to clear £5 million.” The market speculation is that the buyer was Pyotr Aven, board chairman of Alfa Bank and one of Mikhail Fridman’s partners; they have been attempting to sell the bank.

Aven’s collection of Russian art of the avant-garde period between 1890 and 1930 is well-known; he has also led an effort  to guard his investment value by exposing forgeries and false authentications. Aven (right) advertised his collection in the Financial Times in July 2017, when he said he “hopes to be able to persuade the Victoria and Albert Museum [London] to put on a show based around his porcelain collection.

to guard his investment value by exposing forgeries and false authentications. Aven (right) advertised his collection in the Financial Times in July 2017, when he said he “hopes to be able to persuade the Victoria and Albert Museum [London] to put on a show based around his porcelain collection.

In the future, he dreams of a private museum to house his works. Yet he believes they would be overshadowed by other state collections if it were in Moscow, and in London he questions whether there would be sufficient interest. Instead, he is considering Riga, for which he retains an affinity because of his Latvian grandfather.”

A London dealer who knows the identity of the buyer of the Petrov-Vodkin painting refuses to confirm it is Aven. Another source claims that Aven’s buying agent, Alexander Lachman, was visible in the auction room but he was not signaling with his hands. “[Aven] usually gets Lachman to do his bidding,” a source at Christie’s said. Aven was contacted and asked to speak for himself. He declined to do so.

The painting’s value is disputed. “Not one of Petrov-Vodkin’s best, but big,” concedes a well-known expert. “The price is entirely normal,” comments a dealer. “Every two or so years we get a gem of a picture, a once-in-a-lifetime masterpiece and the market reacts.”

The reaction in Moscow is negative. “The sale of Petrov-Vodkin for $12 million [£9.3 million] is the most striking result of the last few years, and I’m afraid that it will remain the only one,” commented Konstantin Babulin, head of the Art Investment auction house in Moscow. “When we made our forecasts, the most expensive sale of Petrov-Vodkin previously was $3,600,000. As the current picture is better, we assumed that it could be worth $7 million, but were afraid of such a figure and corrected to $4.5 million. So even professionals did not expect such sale prices. They are from the category of fantastic results which cannot be explained by the law of the market… This strange sale of Petrov-Vodkin has entered him in the top-ten most expensive [Russian] artists. But for us there is nothing good, and there is no logic in this sale, except for one sad conclusion: it is now impossible to assume the participation of the picture at such a level in the internal market. Now Petrov-Vodkin won’t be bought at a domestic auction. Expensive things will continue to go into international circulation.”

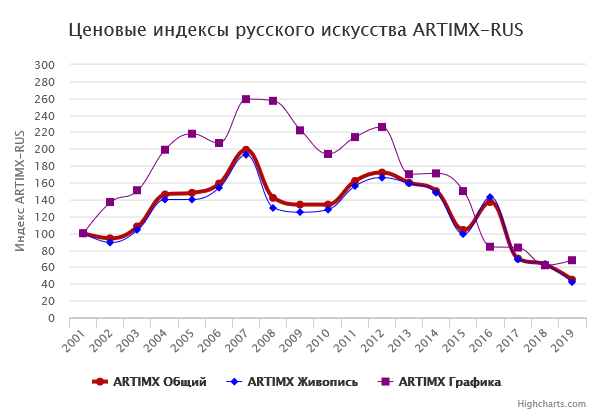

The latest measurement of the index of art prices in the domestic market shows no sign of recovery for paintings.

INDEX OF RUSSIAN ART PRICES, 2001-2019

CLICK TO ENLARGE IMAGE

KEY: Grey=graphic works; blue=paintings; red=all works. Source: https://artinvestment.ru/

Leave a Reply