By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

“He was not a nihilist for nothing!”

This is one of the funniest, and at the same time one of the saddest lines, written by Ivan Turgenev in Fathers and Sons, the novel of his which preserves its contemporaneity through the Russian revolutions better than any other classic of Russian literature.

Appearing to come out of the stream of consciousness of one of story’s characters, the line is also an irony of Turgenev’s — and if you understand that he meant nihilist as a synonym of Russian, it is a warning of great philosophical force for right now. Right now is a synonym for June 22, 1941, when Hitler invaded to destroy the Russians; and for June 24, 1812, when Napoleon tried the same. Those two names can’t be synonyms for Biden because the German and the Frenchman weren’t demented or led by psychopaths.

Turgenev’s line is comic because in thinking the opposite of what the character had said aloud, he was also making fun of himself.

It is sad because nihilism as an idea or an ideology turns out to be pose, a man’s vanity, a will o’ the wisp, in short nothing at all. And it is exposed, dismantled, destroyed by the woman of the story, Anna Sergeyevna Odintsova, who causes the nihilist to fall in love with her, and then in getting him to admit it to her she annihilates – that’s the precise word – every conviction the nihilist said he stood for.

In the plot of the book, this destruction takes place at the midpoint of the story. The man remains alive, as does Odintsova, his destroyer, and both of them spend the rest of the novel compensating for what has happened. But the lines Turgenev wrote as if in Odintsova’s stream of consciousness are terrible. Read them again — she was forced “to look behind her – and there she had seen not even an abyss but only a void… chaos without shape”. This is destruction, not of a man or a woman, but of meaning.

Today this is a warning for Russians facing the attack of enemies determined, after seventy years of planning to destroy them, to finish the job once and for all. In Turgenev’s telling, what had just happened was the destruction of all meaning of what had already happened, interpreted retrospectively. What follows in the tale, and for its readers, is survival after hindsight of the void.

A lot of guff has been written for a hundred and fifty years about what is called the central character of the story, Yevgeny Vasilievich Bazarov the nihilist. This is a mistake. The central character is the woman, Odintsova. It is she who reduces the pretensions, and also all the qualities of the man, to next to nothing. She does so without malice, but with a clarity that ruins Bazarov. This woman Odintsova is in Turgenev’s description a force, almost not a physical body at all.

Turgenev himself was unusually tall – 1.9 metres, or 6 feet 2 inches. At that height it’s impossible not to notice the height of a woman to whom one is attracted – believe me, I too am 1.9 metres, 6 feet 2 inches. And indeed, although most of the tall things in Turgenev’s story are either men or trees, the first glimpse of Odintsova entering a ballroom registers that she is “a tall woman in a black gown”. Bazarov then remarks: “What a face! No one in the room has anything like it.” But that’s the only physical particular he is reported by Turgenev to have acknowledged.

Left: the English translations quoted come from the 1965 Penguin Classics edition, in which the translator was Rosemary Edmonds; Right: the digital text used here to analyse what Turgenev didn’t intend to be understood by readers about his methodical mind, as distinct from his professional intention, was first published just eight years ago -- by the Gutenberg Project in 2015. The English translation used is the 1921 edition by by C.J. Hogarth. Click to open.

Otherwise, Odintsova is described hardly at all – no arms, hands, lips, not even her eyes. These are “brilliant”, then “clear”, and finally “beautiful”, but Turgenev gives them no colour, shape, or size. Fancy a face described without features — impossible you might say. But not in this story.

Turgenev dissembles with Odintsova’s nose and skin in order to demean her: “Her nose – like most Russian noses* – was a trifle thick and her complexion was not translucently clear”. Surrounding Odintsova, Turgenev draws much more distinctive noses, including the nose of the pet Borzoi dog, and on occasion arranges to blow them with special effect. Odintsova is reported to pay special attention to an ancient Greek statue acquired by her late husband – of the Goddess of Silence – whose missing nose Odintsova refuses to replace, and because of that stores out of sight.

Bazarov is revealed to have erotic desire for Odintsova by a passing reference to “her pair of shoulders” – as if she were an unsaddled pony. Much more is revealed in Turgenev’s multiple references to the rustling sound of Odintsova’s silk dresses, explaining that “Bazarov followed [her] with his eyes fixed upon the floor, and his ears open to no sound but the faint rustling of a silk dress.” Odintsova’s silks are black – she was a widow – and Turgenev mentions this colour 19 times. The colour white, on the other hand, appears 31 times; but when Bazarov flirts with another woman, kissing her twice on her parted lips, he does so by reaching across her to select from her bouquet a red rose instead of a white one.

Odintsova and Bazarov try to find complementarity, not in art which Bazarov says he despises, but in botany. Accordingly, Turgenev sets a spray of fuchsias in her hair at a ball. However, the other flowers he writes into the story — which is set in late spring, early summer when there is abundant blossom – are acacia, lilac and roses – these Turgenev fixes to other, lesser characters.

The contemporaneity of Fathers and Sons , along with the originality of Turgenev’s insight, comes at the midpoint climax when Odintsova destroys Bazarov. Thereafter, the tale turns into a conventional 19th century romance in which there is a happy love ending, consummated in marriage for everybody except Bazarov. He dies a painful, possibly self-inflicted death from typhus after doing better at a pistol duel than he had expected. Before Bazarov breathes his last he is visited, and kissed on the forehead, by Odintsova; subsequently she too marries. Presenting that union in his dénouement, Turgenev makes a political statement which readers of today can hardly miss.

“My father will tell you what a loss I shall be to Russia”, Bazarov whispers to Odintsova on his deathbed. “That’s bosh, but don’t disillusion the old man.” Bazarov’s extraordinary self-conviction and ambition for himself are thereby exposed to be the very antithesis of his nihilism. By contrast, Odintsova, according to Turgenev’s epilogue for the surviving characters, “has recently married again, not for love but out of conviction (that it was the reasonable thing to do) a man who promises to be one of the future leaders of Russia.” Turgenev then itemizes what he projects to be the characteristics of the future leaders of Russia — “a very able lawyer possessed of vigorous practical sense, a strong will and remarkable gifts of eloquence. He is quite young still, kind-hearted and as cold as ice.”

It cannot escape readers that in the 162 years since Turgenev wrote that, there has been only one leader of the Russian state to have fitted this bill.

Once met, any man with a heart would want to love Odintsova, and much more importantly, to be loved by her. Bazarov failed and got his dressing-down and his comeuppance. If you are fortunate, you may be loved by a Russian woman of Odintsova’s quality. If that happens to you, you can forget what you’ve been told since this war began about your brothers and sisters, the Ukrainians.

But was the object of the man’s love in this tale the woman at all? Was what we love with passion, what we must defend and fight to save if we are to keep our honour, a woman — or is it something else? War shortens the time for such speculation, disallows the risk of such choice.

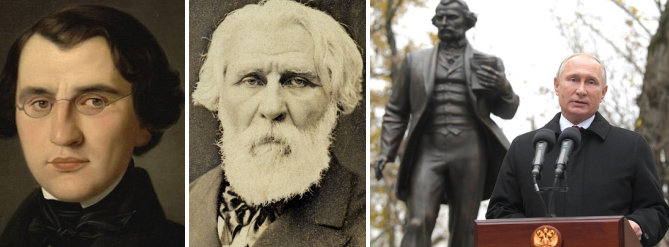

NOTE: The lead images, left to right: Turgenev, aged 25, painted in 1843-44 by Eugene Lami; centre, Turgenev in a photograph of 1880 aged 62; right, President Vladimir Putin opening the Turgenev House Museum on Ostozhenka Street in Moscow, on November 10, 2018, the 200th anniversary of the writer’s birth.

[*] Turgenev’s characterisation of Russian noses is more than a national snub. In Rudin, for example, Turgenev’s first novel written five years earlier in 1856 – a self-portrait, it is said -- there are seven noses, none “thick”, and one, that of one of Rudin’s love interest in the tale, appeared so: “Her straight, ever so slightly tilted nose would have been enough alone to drive any man out of his senses, to say nothing of her velvety dark eyes, her golden brown hair, the dimples in her smoothly curved cheeks, and her other beauties.” Rudin himself appears with “his quick, dark blue eyes, a straight, broad nose, and well-curved lips.” In Virgin Soil, Turgenev’s last novel (1877), there are 21 noses, including one “fine Roman nose”, “large aquiline nose”, “hooked nose”, “purple nose”, “flat nose”, “broad nose”, “snub nose”, and a “handsome nose”. There are many women’s noses in Turgenev’s other novels, but in the complete works no nose was ever censured like Odintsova’s. In real life, Turgenev’s love, Pauline Viardot-Garcia, did not have a thick nose. As the lead images show, Turgenev did.

Leave a Reply