By John Helmer, Moscow

Roman Abramovich (lead image) is the leading shareholder of the Russian steel, iron-ore and coal mining group called Evraz. Among Russia’s leading steel groups, it ranks second in output of crude steel; fourth in market value. It is the leader in indebtedness.

By international measures, Evraz also leads its Russian peers in its record of controlling noxious air and water emissions from mill and mine operations. CDP, an international agency for monitoring industrial pollution, reported a year ago its global answer to the question, “who’s ready to get tough on emissions?” Evraz came 12th in CDP’s table of the world steel emission control leaders; no other Russian steelmaker was ranked. That was not exactly a commendation in international terms. According to CDP, “Evraz ranks third last. It performs among the bottom companies on our emissions and energy benchmarking, and does not disclose forward-looking reduction targets, or any participation in research toward breakthrough emissions reduction technologies.

If you live in Novokuznetsk city, where Evraz operates two steel plants, the company’s international status is too good to be true. For the past decade, Evraz has been under local court and federal orders to put a stop to its waste water pollution by building a new water treatment plant. The company refuses. It won’t explain, hoping that its influence with city, regional and federal government officials, will ensure that there will no enforcement, and no news of this either.

Six Russian steelmakers are listed on international stock exchanges; five them on the London exchange, and one, Mechel, on the New York Stock Exchange. This is misleading; they are all one-man businesses; most of the cash dividends go straight into their pockets.

Novolipetsk Metallurgical Combine (NLMK), owned by Vladimir Lisin, leads the sector with a market capitalization of $14.2 billion, It produces 16 million tonnes of crude steel each year, way ahead of its nearest Russian rival. In market cap Severstal, owned by Alexei Mordashov, comes second at $13.2 billion; its annual output is 11.6 million tonnes of crude steel . Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Combine (MMK), owned by Victor Rashnikov, produces more steel – 12.5 million tonnes – but trails in market value at $9.1 billion.

Outside the top four, Dmitry Pumpyansk’s pipemaking combine TMK is valued on the London Stock Exchange at $1.4 billion; Mechel, the property of Igor Zyuzin, is valued at $1.03 billion. Zyuzin’s benighted story can be followed here. He is the worst polluter of the Russian steelmakers, and is responsible for most of the murk which blankets Chelyabinsk city regularly in winter; for details, click.

At a convention of the Russian Union of Industrialists and entrepreneurs in 2016, left to right, Vladimir Lisin, Alexei Mordashov, and Igor Zyuzin. Seated to their right, apart, was Victor Rashnikov. Roman Abramovich has almost never been photographed in the company of his fellow steelmakers.

Abramovich had the reputation of being light-fingered during the asset acquisition stage of his business career. Tested for truth-telling in the London High Court by Boris Berezovsky, the latter was judged to be the bigger liar; click to read.

Debt weighs heavily on Abramovich’s reputation. Evraz ranks last of the top four in market cap at £4.6 billion ($6.1 billion), and the company is carrying $4.3 billion in net debt – Abramovich is the most heavily indebted of the major Russian steelmakers; only Zyuzin of Mechel owes more money (about $7.4 billion).

NLMK owes $3.4 billion (net debt); Severstal, $827 million; and MMK, $239 million. Their stories can be followed by clicking on their names.

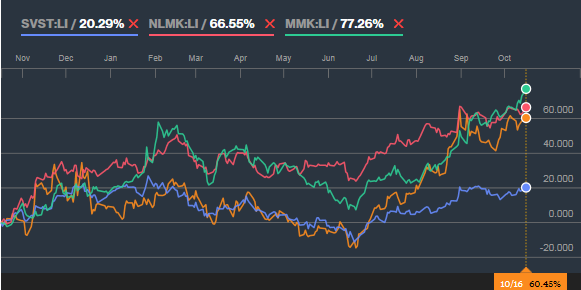

SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORIES OF THE TOP FOUR RUSSIAN STEELMAKERS

KEY: yellow=Evraz; pink=NLMK; green=MMK; blue=Severstal. Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/EVR:LN

Since the start of this year, with the rise of iron-ore, coal and some steel prices, and the beginning of recovery in Russian domestic industrial demand, the chart shows much the same up and down trend for all the steelmakers. MMK’s share price has gained relatively faster than its peers, while NLMK has remained the most stable at the top of the chart. Evraz, a long steelmaker, has managed to best Severstal, a flat steelmaker, in stock market favour since June. Long steel products – reinforcement bar, beams, wire, rails and wheels – are intended for construction, infrastructure and railways. Flat steel products – sheet and plate – are used in cars, ships, white goods, and pipes.

The Kemerovo region governor, Aman Tuleyev (right) , was especially helpful in the court- adjudicated bankruptcies through which Abramovich and his business associates got Evraz its start. The governor has also been helpful in administering the mine safety codes and emission regulations affecting Evraz’s workers and the towns and cities where they live. He still does. What in pre-Soviet days was called the city of Kuznetsk (“smith”), in southern Kemerovo, hosted two new steel plants and several coalmines as part of the Joseph Stalin’s crash industrialization programme. It then became Novokuznetsk before turning into Stalinsk between 1932 and 1961, reverting back to Novokuznetsk from then on.

in the court- adjudicated bankruptcies through which Abramovich and his business associates got Evraz its start. The governor has also been helpful in administering the mine safety codes and emission regulations affecting Evraz’s workers and the towns and cities where they live. He still does. What in pre-Soviet days was called the city of Kuznetsk (“smith”), in southern Kemerovo, hosted two new steel plants and several coalmines as part of the Joseph Stalin’s crash industrialization programme. It then became Novokuznetsk before turning into Stalinsk between 1932 and 1961, reverting back to Novokuznetsk from then on.

There was an appellation change too, at the Kuznetsk Lenin Iron and Steel Plant. First it shortened to KMK, and then in 2003 to Novokuznetsk Iron & Steel Plant (NKMK). In 2011 the Evraz management combined the plant with West Siberian Iron & Steel (Zapsib), also located in Novokuznetsk city, and also one of Abramovich’s successful takeover targets. From then on the two mills and companies became known as one; that’s the wholly owned Evraz subsidiary referred to in company reports as ZSMK, Zapsib for short.

The 400-year old city of Kuznetsk started as a Cossack settlement on the confluence of the Tom and Aba rivers. This is how they look today:

Left: the Tom River in Novokunetsk city; right, the Aba River.

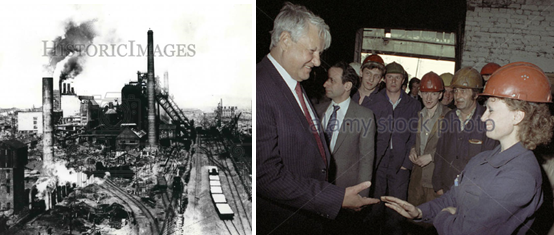

KMK looked like this in the 1930s (below, left). In 1993, the plant was visited by then President Boris Yeltsin (right).

President Vladimir Putin hasn’t followed, although he has met Tuleyev many times in Moscow and in Kemerovo, and attended the region’s worst coal mine disaster in May of 2010. Putin ordered Abramovich to meet him in Novokuznetsk, to discuss the aftermath of the Evraz-Raspadskaya coalmine explosions at Mezhdurechensk, 80 kilometres to the east of Novokuznetsk. Ninety-one miners and rescuers were killed. Putin appeared to blame the company in his initial public remarks.

Putin, accompanied by Tuleyev, at the Raspadskaya disaster memorial, May 2010. Source: http://johnhelmer.org/the-wages-of-sin-putin-appears-to-shift-liability-for-raspadskaya-mine-deaths-to-company/

Ahead of next year’s presidential election, the Kremlin said last week it wants to keep Tuleyev, now 73, ailing, and in his 20th year as governor, in power until after the poll due next March.

Late last month local metropolitan media reported that Novokuznetsk had been named one of the 20th worst cities for air pollution across Russia. The measurement data came from the federal Ministry of Natural Resources and its environment watchdog, Rospriradnadzor (RPN). The worst pollutant in the city air was sulfur dioxide; the culprit identified in last month’s reports was the combination of the Novokuznetsk and Zapsib steelmills.

Since 2014, according to this city report, the incidence of asthma and other respiratory illnesses has grown significantly worse as a consequence of the air pollution.

Last month also, in a report dated September 12, O.V. Beletskaya, the Novokuznetsk assistant prosecutor in charge of policing water pollution in the metropolitan area, announced that uncontrolled and illegal emissions had been uncovered by inspectors testing river water during the first half of the year. The Beletskaya report says: “in the first half of 2017 the office of the Prosecutor assessed water activities by 17 companies that are environmental pollutants on the territory under the jurisdiction of Novokuznetsk Interdistrict Office of the Prosecutor for Environmental Protection. In the course of inspections violations were found of the rules of water use in the discharge of wastewater into surface water bodies [rivers], expressed in the discharge of pollutants in the absence of permits, as well as excessive concentrations over the permit levels.”

“The main causes and conditions contributing to violations in this area,” Beletskaya listed as inadequate sewerage treatment plants and obsolete or decrepit water treatment plants discharging from industrial plants into the city’s rivers. “During the first half of 2017, the Prosecutor brought 33 cases of administrative offences in the sphere of water management; issued 12 official notices requiring elimination of infringements of the law….[and filed] in local courts statements of claim to compel users of wastewater treatment facilities.” Evraz’s plants in the city were named by Beletskaya as among the leading offenders.

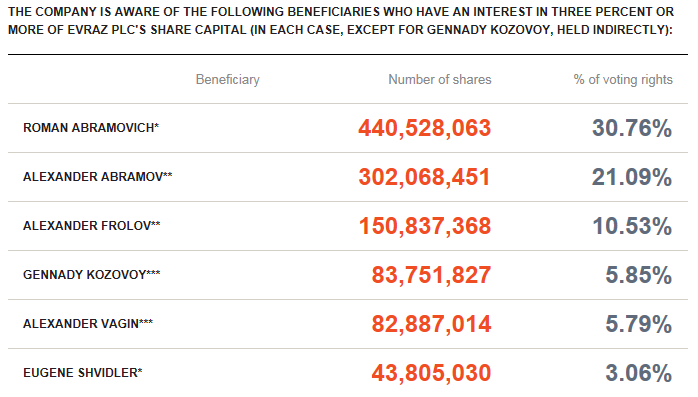

This was no news in the city. More than a decade ago, Evraz had been taken to court by RPN and the prosecutor for the same wastewater violations by its steelmaking operations. Then, as now, the men responsible were the leading shareholders of the company, as well as the group’s chief operational executives:

CONTROL SHAREHOLDERS OF EVRAZ, 2017

Left to right: Alexander Abramov, founding chief executive of the group and a current board director; Alexander Frolov, successor to Abramov as chief executive, the current chief, and a board director; and Evgeny Shvidler, one of the founding shareholders and board directors. See: https://www.evraz.com/governance/directors/

Just three weeks ago, in an interview placed in Kommersant on September 25, Maxim Epifantsev, director of Evraz’s environmental compliance operations, distinguished between Russian and international water emission standards by saying: “the main differences in the definition of standards of environmental impact [include], for example, in Russia much tougher requirements for the quality of discharged waters. In the end, there are paradoxes when the ratio of iron content to the discharged water of the plant is tougher than for drinking water.” This is true. It’s also a baldfaced lie about Evraz’s failure to comply with the standards.

After inspections during 2005 led to court action by the regulators at RPN, Evraz was ordered to close the old water-treatment plant at the Novokuznetsk steelmill. If the mill was to continue operating, company officials were told, they were required to sign an agreement to construct a a new plant; this was estimated at the time to cost more than $90 million. Abramovich and his managers refused, and got the Novokuznetsk mayor and the regional governor to claim that the court enforcement threatened jobs and taxes. Two years later, the head of environmental control at the Natural Resources Ministry in Moscow, a gadfly named Oleg Mitvol, decided to intensify the campaign against Evraz.

Mitvol (right) explained to me at the time: “There was a court decision in 2006 on  the two enterprises. We demanded immediate suspension of the mills, but the court decided that there was a social aspect, like jobs, the economy of the region, etc. So the court ruled in favour of a delay for two years, during which the [two Evraz units] should improve the ecology….Now we will calculate the damage cost for [waste water] emissions by the new coefficients we have [calculated]. We will demand the closure of [steelmaking], with bailiffs to enforce the court ruling of 2006.” Read that story here.

the two enterprises. We demanded immediate suspension of the mills, but the court decided that there was a social aspect, like jobs, the economy of the region, etc. So the court ruled in favour of a delay for two years, during which the [two Evraz units] should improve the ecology….Now we will calculate the damage cost for [waste water] emissions by the new coefficients we have [calculated]. We will demand the closure of [steelmaking], with bailiffs to enforce the court ruling of 2006.” Read that story here.

What happened next was that the Evraz board decided to invest $440 million in a new production line at the plant for rails, procurement of which had been guaranteed by the Russian state railways. The company not only felt safe spending the new rail plant money; it also felt safe ignoring the water-treatment plant order, which it had signed earlier. A review of Evraz’s annual reports, financial statements, and presentations in the decade since 2006 reveals just how confident Abramovich & Co. were that there would be no enforcement of the water regulations; they were also confident noone would notice.

In 2006, there was extensive reporting in Evraz documents of anti-pollution initiatives. For example, “during 2006 Evraz Group launched its first social initiative project ‘City of Friends—City of Ideas’. The aim of the programme is to support promising ideas and projects that can contribute to regional welfare. In 2006, local societies and youth organisations of Nizhny Tagil, Kachkanar and Novokuznetsk competed for grants to implement development projects. Expenditures on the implementation of the programme ‘City of Friends—City of Ideas’ totalled approximately US$200,000. The programme supports inter alia family values as a vital component for the social value structure and orphanages and implements various sporting and cultural measures.”

“Evraz Group makes every effort to reduce the adverse impact of its business activities on the environment. Evraz Group’s subsidiaries possess all necessary environmental licences for the use of water resources, water discharges, air emissions, waste disposal and waste management pursuant to local laws and regulations.” There was no mention of RPN’s violations report or the court orders for remedy.

Instead, the company claimed to have decided on a “capital expenditure programme of approximately US$575 million [which] will mainly target ongoing projects to increase operational efficiency. Included in these projects is the relining of the Zapsib blast furnace. This investment will decrease crude steel output for 2007 by approximately one million tonnes. Additionally there will be the closure of all open hearth furnaces located in the centre of Novokuznetsk, a city with population of over 550,000 people. Such action will eventually result in the improvement of the environment as well as increasing the operational efficiency of the plant.”

Eventually can be a long time. According to the company’s financial report for 2006, “Evraz has a constructive obligation to reduce environmental pollution and contamination in accordance with an environmental protection programme. During the period 2007 to 2012, Evraz is obligated to spend approximately US$158 million on the replacement of old machinery and equipment which will result in reduced pollution.”

In 2008 Evraz reported it was paying for, or at least valuing water rights at $63 million – that’s to say, the rights to dump steelmill waste in the river. Counting this on the asset side of the company’s balance-sheet, this was a tenfold increase from the $6 million entered in the 2006 accounts. It also counted as the right to exceed the water pollution standards – at two-thirds of the cost of the new water-treatment plant. Evraz’s auditors weren’t told to include that on the liability side of the balance-sheet.

In 2009 Evraz admitted in its financial report that there might be a liability, if either Tuleyev or Moscow took enforcement action. “Environmental risks expose companies to potentially significant obligations. The exposure is twofold: (1) obligation to third parties for bodily injury or property damage caused by pollution and (2) obligation to governments or third parties for the cost of removing pollutants together with severe punitive damages. The Group mitigates these risks through the provision of all essential regulatory documentation and compliance with all operating permissions in respect of all environmental impact activities in 2010 and beyond, regulatory standards for air pollutant emissions, regulatory standards for water pollutant dumping and fixed limits for waste disposal.”

The risks didn’t materialize. In 2012 Evraz reported spending money on “aquatic therapy” for impoverished and ailing children in the city. In 2013 the company said: “ The objective of the Company is to use water resources efficiently and to prevent any negative impacts on water quality through environmental incidents… In 2012, EVRAZ adopted a new water management strategy for EVRAZ ZSMK and Yuzhkuzbassugol which has already significantly improved the water management performance of these operations. At EVRAZ ZSMK a new local water rotation cycle with a sludge dewatering installation that re-uses dewatered sludge in production as a raw material was introduced and this reduced fresh water consumption by 4.7 million cubic metres. In total, the water management programme reduced water consumption by 11.5 million cubic metres in 2013.”

“In 2013, EVRAZ provided assistance and funding for a number of projects including equipping children centres, orphanages, schools and playgrounds in Novokuznetsk, Tashtagol and Nizhny Tagil and expanding its programmes on hippotherapy and aquatherapy in the Urals.”

In 2014 the company said it wasn’t forgetting water, at least the water in excursions for orphans. “EVRAZ continues to support orphanages, providing equipment, educational materials, clothes and New Year presents. In Siberia EVRAZ organised a boat tour to Evenkia for the children from one of the orphanages of Novokuznetsk.”

The next year, Evraz claimed, “in 2015, EVRAZ supported the renovation of the Garden of Steelworkers in Novokuznetsk. Every year, the Group organises a competition for the best projects for residential courtyards. The winners receive playgrounds for their yards, and nine were installed in 2015. In 2015, EVRAZ supported the reconstruction of the road on the Kuznetsky bridge in Novokuznetsk.”

In 2016, the annual report acknowledged that enforcement was intensifying, and that fines for the company’s violations were growing. “Steel and mining production carry an inherent risk of environmental impact and incidents relating to issues as diverse as water usage, quality of water discharged, air emissions, waste recycling, tailing management, air emissions (including greenhouse gases), and community satisfaction. Consequently, EVRAZ faces risks including regulatory fines, penalties, adverse impact on reputation and, in the extreme, the withdrawal of plant environmental licences, which would curtail operations indefinitely…Environmental risks matrix is monitored on a regular basis. Respective mitigation activity is developed and performed in response to the risks….”

“The Group’s non-compliance-related environmental levies and fines increased by 7 % to US$2.1 million in 2016 from US$2.0 million as it was in 2015. No significant [sic] environmental permits or licences were missing or revoked in 2016, although the Russian government has tightened the requirements for obtaining environmental permits and licences. This was the reason for the delay in issuing some of the new permits, which led to non-compliance levies of US$ 0.5 million. EVRAZ’ assets had no significant environmental incidents or material environmental claims during the reporting period.”

To cement one decade of non-compliance for the future of another decade, and deterring local prosecutors like Beletskaya, as well Mitvol’s successors in the Moscow ministry, from resurrecting the enforcement campaign, Evraz announced it had drafted and signed this pact with all the regulators.

Evraz’s spokesman in Moscow Vsevolod Sementsov, and the managing director of NKMK, Alexei Yuryev, were asked to say whether or not the new $90 million water-treatment plant has been built. They refuse to answer.

The same question was asked of Tuleyev’s spokesman, Alexei Dorongov; Sergei Kuznetsov, the mayor of Novokuznetsk city; Irina Savina, head of the Novokuznetsk Municipal Committee for Pollution and Environment; Galina Barabash, her counterpart at the Kemerovo regional department for pollution and environment; Sergei Shatirov, a local member of the Kemerovo region legislature; and two officials of Rospriradnadzor, Irina Klimovskaya of the Kemerovo region branch, and Yevgeny Novikov, the spokesman at Moscow headquarters. All of them have refused to say a word.

It might be thought that non-governmental organizations in Kemerovo or Novokuznetsk would be as concerned as their anti-pollution charters oblige them to be; at the very least, they ought to be able to say whether Evraz has built the new water-treatment plant, and if not, why not. Three such organizations were contacted – Green Patrol; EcoDelo; and the Novokuznetsk Environment Protection Committee. They too are keeping their mouths shut.

So is Abramovich. While he undergoes his regular aqua therapy, his spokesman John Mann was asked to say if Abramovich had drunk the water when he visited Novokuznetsk, and what comment he night make about his company’s refusal to implement the waste water controls in Novokuznetsk. There has been no response.

Abramovich, photographed (left) by paparazzi commuting between his motor yacht and his home at the French Mediterranean resort of Antibes, the Château (sic) de la Croë. Abramovich is domiciled between his boat, the French home, and town and country homes in the UK. The 75th Street, New York, homes Abramovich also owns are believed to be part of his current divorce settlement, and he won’t be living there. For more on Abramovich’s commitment to ecologically safe water, read this and this. Because he was a regional governor of Chukotka, Abramovich was obliged to identify his offshore homes in 2011; click.

Leave a Reply