By John Helmer, Moscow

As the Kremlin’s apparatchik for the state aluminium monopoly, Oleg Deripaska (lead image), chief executive of United Company Rusal, has a personal price problem which threatens to turn into an income problem for Russians. If it does that, and loss of income turns into negative opinion polls and protest votes, Deripaska has a political problem with President Vladimir Putin.

Rusal announced last week that because the price of aluminium in global trade is falling, driven downwards by recession in demand and increasing Chinese production for export, there is likely to be a new cut in Russian smelter output. The company says it “is considering further aluminium production cuts totaling approximately 200 thousand tonnes per annum.”

This Rusal cut comes on top of 316,000 tonnes cut in 2013; another 256,000 tonnes cut in 2014; and 38,000 tonnes cut in the December quarter of last year. According to the new Rusal production report for the fourth quarter and the full year, the curtailment of aluminium supplies is “supporting the LME aluminium price and premiums are expected to stabilize at current levels in 1Q16. The upside of the aluminium ‘all-in’ [London Metal Exchange price plus premium] price on the short-term horizon will be dependent on FX rates, underlying energy prices and the positioning of commodity funds based on their views of the Chinese economy… Overall we expect 1.2 mn tonnes of global aluminum market deficit in 2016 compared to 0.6 mn tonnes of surplus in 2015.”

This year’s cut – 6% of last year’s total output — will cause Russian job and income losses. Or else Deripaska must absorb the losses on his profit line because the political survival of the government is at stake.

When the price of aluminium was rising, Rusal’s profits went to pay its foreign and Russian bank (state bank) debts. These were run up by Deripaska when he had the ambition to be tsar of all Russian metals, including aluminium, copper, nickel, platinum group metals, molybdenum, and coal. Deripaska, plus what the US Treasury calls his “cronies” on the Rusal board, have hung on to their seats, jobs, and compensation despite the collapse of the aluminium price, and despite Rusal’s costly efforts in the UK courts to preserve the old system of delayed metal delivery and warehouse storage premiums. The story of the speculation on the aluminium premium can be read in detail here.

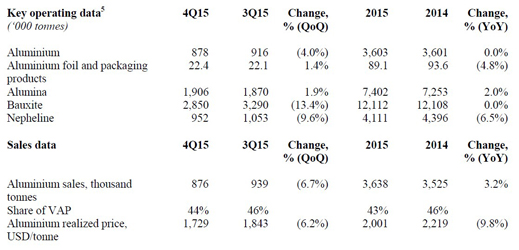

RUSAL PRODUCTION AND SALES REPORT, IN TONNES, FOR 2015

Source: http://rusal.ru/upload/uf/9fb/11%2002%202016%20RUSAL_Trading%20update%204Q2015.pdf

The biggest cuts in production have come in plants located in regions southwest and northwest of the Urals. Deripaska has no intention of restarting these smelters. “The Company does not plan on restarting the aluminium smelters idled in 2013”, the new report said last week. These were the smelters which in 2006 had belonged to Victor Vekselberg’s Siberian Ural Aluminium (SUAL) company — Volkhov (Leningrad region), Bogoslovsk (Sverdlovsk), Volgograd, Nadvoitsk (Karelia) and Uralsk (Sverdlovsk – pictured below).

For years Vekselberg had fought off Deripaska’s attempts to raid his assets. He was intending to list SUAL on its own on the London Stock Exchange when in September 2006 Deripaska got Putin’s backing for a final raid. Vekselberg was obliged to give up his independent listing and merge his assets with Rusal, taking an IOU from Deripaska in the form of a minority shareholding in the enlarged company. He was promised a substantial value gain when Rusal listed on London in the grander size. But Deripaska failed to get London Stock Exchange listing approval – several times. To meet his obligation to Vekselberg, along with Mikhail Prokhorov and other minority shareholders, he was forced to take his listing where he could find it, and on terms so embarrassing they were kept secret. Either allow Muammar Qaddafi’s son Saif and the Libyan Investment Authority to buy the shares at an agreed valuation, or else the Russian state banks would have to do so. That story has been told here.

The history of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange listing has been catastrophic for the free-float shareholders of Rusal, as well as for Vekselberg and Prokhorov. The company started at HK$10.80; hit peak of almost $13 in 2011. Since then it has fallen:

RUSAL SHARE PRICE HISTORY SINCE LISTING IN JANUARY 2010

Source: http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/486:HK

The Rusal share now trades at HK$2.33. It dropped as low as $2.13 in January. The market capitalization is HK$35.4 billion (US$4.6 billion). That’s about two-thirds of the company’s aluminium sales revenue last year; it’s half the sum Rusal owes its creditors. Rusal insiders in Moscow say the share price would be even lower if not for a company-paid scheme of share buying and price support, which, the sources add, can be followed at most Hong Kong trading sessions around 2 in the afternoon.

Last week’s fourth-quarter production and trading report shows why there is so little market confidence. Aluminium production1 in the quarter fell 4% to 878,000 tonnes; aluminium sales fell by almost 7% to 876,000 tonnes. Rusal explained this by saying it has been exporting and stocking unsold metal abroad in anticipation of releasing it for sale in the current quarter, or maybe next.

The bottom line reported last week was what the company calls its “average realised price”. When Rusal sells its aluminium, the contracts combine the London Metal Exchange (LME) base price for physical metal, plus a premium for warehouse storage and delivery when the aluminium buyer wants it. That premium has been going up for several years. It peaked at $424 per tonne in the March quarter of 2015 when the LME price Rusal reported was $1,801. From then on the combination of LME price plus premium – which itself varies between the North American, European and Japan markets – has been dropping. Together, they averaged out at $2,001 per tonne – 10% less than the year before.

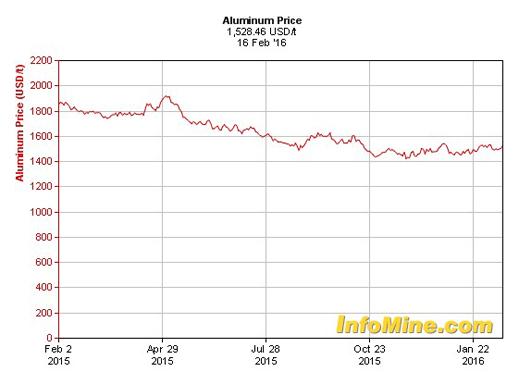

By contrast, in 2012, the LME price was much higher, averaging $2,018 for the year, and falling . But the premium was much smaller — $208 – and rising to prop up a sales price of $2,218. This is how the LME benchmark price fell over 2015:

Source: http://www.infomine.com/investment/metal-prices/aluminum/1-year/

According to Rusal, there was also a sharp fall in premiums in the European and Japanese markets during the year – the European premium fell to a low of $57.50 between July and the end of September. Click for chart.

Then during the final quarter the premium picked up again, Rusal reported last week. “Commodity grade premiums recovered during 4Q15 after they dipped below transportation / insurance component levels in September and October 2015. EU [European Union] premium (duty unpaid) increased from USD65/t to USD117/t during the 4Q15 and stabilized at USD100/t in the middle of January 2016. Japan’s 1Q16 aluminium premiums were set at USD110/t growing 22% QoQ on falling local inventory and higher premiums across other regions.”

The dwindling of the premiums was bad for Rusal’s revenues, its net profit line, and its ability to service its debts. It fought the London Metal Exchange (LME) in the UK courts to hang on to the old, inflated-price speculation system. It lost. Here’s the story. Here’s the outcome as it struck Rusal’s balance-sheet, last reported in October 2015.

The premium story was bad for Rusal’s image. Metal producers like to seem friendly towards their customers; the physical aluminium buyers weren’t well disposed to a system which demanded signatures on contracts of sale proposing one price, the LME base price, for the metal; and a second price for getting the metal out of warehouse and delivered to the customer – the premium. What exactly was the price, metal buyers were asking, and if there were two prices moving up and down independently of one another, how could suppliers forecast the supply price when they were calculating their own production costs, their selling prices, and their profit margins?

In February 2014, a US industry publication complained “the end user [of aluminium] is bearing an increased cost they are currently unable to hedge. So who will come to the rescue? Market forces, of course, possibly with a helping hand from the venerable CME [Chicago Mercantile Exchange] Group. Market players are clamouring for the CME to offer an ‘all in’ aluminum contract that will allow purchasing managers, scrap dealers and manufacturers to protect themselves from runaway costs. Why CME? Many worry the London bourse [the London Metal Exchange, LME] won’t be able to fix its product anytime soon… Market players are frustrated because while the cash price of aluminum has fallen the premium has doubled in the past few weeks. The problem is the slow delivery of aluminum from the big warehouses in places such as Detroit.”

This was an advertisement against the way in which Rusal, and its shareholding partner and principal metal trader, Glencore, had been managing the trade. It was an advertisement for the Chicago exchange to beat out its London rival, and also steal a march on price reporting media whose daily aluminium prices are often included in sale-and-purchase contracts for metal. One of these is the US agency which has enjoyed Rusal payola over the years – Platts Metals, owned by the McGraw-Hill Financial group of New York. Rivals to Platts in this business include ThomsonReuters and Metal Bulletin, both of London. The business of publishing prices can be lucrative — and crooked.

In September of 2014, Rusal sales director, Steve Hodgson (right), declared he was in favour of a customer-friendly price benchmark, and happy to shake hands on aluminium contracts with Chicago pricing, not London pricing – the CME, not the LME. “What has really changed in terms of the risk profile,” Hodgson told Open Markets,“is how to manage the premium. The premium today is 20-22 percent of total price and generally un-hedgable.” Hodgson issued his endorsement of the CME benchmark just days after CME launched its first North American physically delivered аluminum futures contracts. “We believe that it will allow participants to better manage their price risk and will serve as the premier price reference for the North American aluminum industry,” CME said at the time.

In September of 2014, Rusal sales director, Steve Hodgson (right), declared he was in favour of a customer-friendly price benchmark, and happy to shake hands on aluminium contracts with Chicago pricing, not London pricing – the CME, not the LME. “What has really changed in terms of the risk profile,” Hodgson told Open Markets,“is how to manage the premium. The premium today is 20-22 percent of total price and generally un-hedgable.” Hodgson issued his endorsement of the CME benchmark just days after CME launched its first North American physically delivered аluminum futures contracts. “We believe that it will allow participants to better manage their price risk and will serve as the premier price reference for the North American aluminum industry,” CME said at the time.

Rusal was in favour, Hodgson was quoted as saying too. “The CME contract offers two important distinctions… The new contract is ‘highly regionalized’ which helps consumers in the local environment and it offers a new platform outside of the LME.It does give consumers the option, the choice, to use a different platform.”

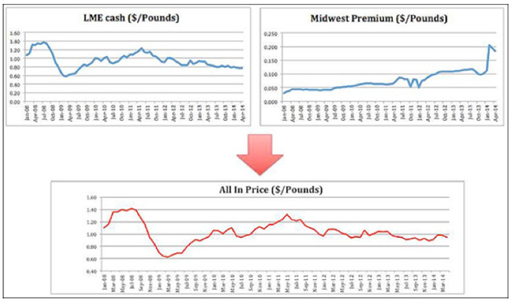

This pointed to CME’s next moves – offering an aluminium contracting benchmark in the two non-American markets which count most to Rusal – Europe and Japan. Throughout 2014 the CME was telling the non-American trade their price dealings were “not in line with the prices seen by commercial buyers and industry analysts in North America. For the past few years, this decline in the LME aluminum price has been offset by a surge in the US Midwest (MW) premium which has led to a situation where the MW premium represents an ever-increasing percentage of the all-in cost. The disconnect between the price quoted on the London Metal Exchange and the deliverable price of aluminum has made it increasingly difficult for hedgers and investors to use the LME contract as their benchmark for physical aluminum.”

The disconnect or price divergence between the falling metal price benchmark of the LME and the rising premium was handily illustrated by the CME this way:

According to CME, “the price that producers, manufacturers, analysts and investors are trying to forecast roughly translates to the LME price + the MW premium. The CME Group’s Midwest Premium contract (AUP) helps commercial market participants hedge the MW premium portion of their risk, but a mix of two price markers is not an ideal situation for anyone.”

In May 2015, CME introduced its all-in benchmark for European trades of aluminium. The following September, it unveiled the all-in Japan market benchmark. Removing premium volatility and counting premiums more precisely, CME told European traders, the new benchmark “will be the first viable exchange-traded futures product to enable customers and market participants to hedge their exposure to the European aluminium premium.” According to the CME, “the Aluminium European Premium futures contract will be 25 metric tons in size and will be financially settled against the Metal Bulletin assessment of aluminium spot price transactions in Europe.”

Metal Bulletin (MB) is the property of London-listed Euromoney Institutional Investor Plc. Part of Euromoney’s business publishing and conferencing divisions, MB generates between 10% and 15% of the group’s revenue total, and about the same percentage of its brand book value. With a 35% operating margin MB’s profitability is higher than for other business publishing brand-names in the group.

The role of Metal Bulletin is also important to Rusal. The London-based metals publication has employed Christopher Evans (right) as its specialist for reporting metals prices between 2003 and 2008. According to his public resume, Evans moved from the Metal Bulletin price desk to the LME where he directed “commercial strategy in London, working with the market to develop and market new products.” He left the LME in August 2013 to set up his own company. Its purpose — “to develop new price benchmarking mechanisms for commodity markets.”

The role of Metal Bulletin is also important to Rusal. The London-based metals publication has employed Christopher Evans (right) as its specialist for reporting metals prices between 2003 and 2008. According to his public resume, Evans moved from the Metal Bulletin price desk to the LME where he directed “commercial strategy in London, working with the market to develop and market new products.” He left the LME in August 2013 to set up his own company. Its purpose — “to develop new price benchmarking mechanisms for commodity markets.”

This is now what Rusal has engaged Evans to do from the office of Rusal Marketing GmBH. According to the December 21, 2015, press release Evans has been appointed “Project Director for Price Benchmarking. Chris Evans will be responsible for maintaining the effectiveness of current price discovery mechanisms as well as working with customers to implement alternative pricing options.” Hodgson was quoted as adding “Chris’s appointment represents our commitment to play a leading role in evaluating alternative price discovery mechanisms for our customers as well as to effectively contribute to the many changes that are taking place with existing exchange traded benchmarks.”

Appointments of midlevel experts and consultants don’t usually rate this much notice, and Rusal’s Swiss operations are usually invisible. They are located at Baarerstrasse 22, Zug. That’s a couple of miles south from the headquarters of Glencore at Baarermattstrasse 3, Baar. Evans works for Hodgson in Rusal’s sales department, but he coordinates with Glencore, the trader and 8.75% stakeholder in Rusal. For the relationship between the two companies and between Glencore’s chief executive Ivan Glasenberg and Deripaska, follow the ins and outs here. If Evans needs to check with Glasenberg on what price Rusal metal contracts should be fetching, he can catch the Baarerstrasse bus no. 4, and be with him in less than 15 minutes.

Rusal insiders at the Moscow headquarters say they saw the December notice but they have no idea what Evans does. “As usual, it seems Deripaska has not informed too many people in the office about what he is doing,” according to a Moscow source. He acknowledges that the relationship with Glencore is top-secret inside Rusal. Evans cannot be contacted. Rusal’s press spokesman Vera Kurochkina refuses to answer questions.

Aluminium traders in Switzerland and London say they aren’t sure what the price benchmarking project means. “That’s a job description I haven’t ever come across before,” said one trader, “and I wonder whether it is indicative of a desire to try and move away from straightforward LME pricing, possibly as a result of their [Rusal’s] little squabble with the LME. In my experience. benchmarking of prices is a concept eagerly embraced when prices are pushed too far one way or the other (either for producer or consumer) and is in reality pretty meaningless.”

A Swiss source disagrees. “Price needs buyers and sellers to agree. So benchmarking isn’t a question of how producers can maximize anything at the expense of buyers. It’s more question of what price benchmark generates the most predictability for both sides. Maybe that’s what Rusal is studying.”

A London metals analyst said: “I have absolutely no idea. I noted the appointment and will look forward to meeting Mr Evans when he’s next in London so he can illuminate me.” A Swiss trader adds “I have no idea what these changes really mean as I am too far away from the action around Deripaska. Most certainly they don’t mean too much. Something cosmetic, as usual.”

NOTE ON THE PERFORMANCE OF THE CME ALUMINIUM BENCHMARKS

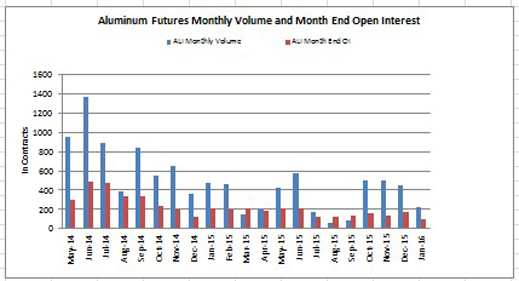

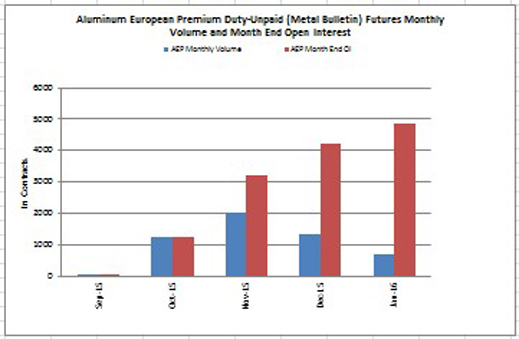

Following publication of this report, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) provided these charts to indicate the contract volumes for the new CME aluminium benchmarks since their introduction.

Blue signifies the contract totals for the month; red signifies the volume of the end-of-month open interest . To understand what these terms mean in the trade, volume (blue) represents the total number of contracts traded in the month. A higher blue bar on the chart means that trading activity was heavier for that month; lower bars mean that trading activity is falling by the month. Open interest (red) is the number of open or outstanding contracts in the month for which the holders are obligated to the Exchange because no offsetting sale or purchase has been made against it. Open interest is frequently used as an indicator of the level of commercial as opposed to speculative activity in a futures or options contract for the metal, since hedgers are much more likely to hold long-term positions. Volume measures the pressure behind a price trend, up or down; open interest measures the flow of money into the futures market.

Aluminum futures (ALI) since inception

Aluminium European Premium futures (AEP) since inception

The comparable London Metal Exchange (LME) data for aluminium contract volumes for one previous month can be looked up here; historical series must be purchased. Open interest volumes by month must be purchased. Compared to the CME volumes, the LME volumes are much, much larger.

Leave a Reply