By John Helmer, Moscow

If you believe what RusPetro Plc says, this loss-making venture on a small oil patch in Khantiy-Mansiysk — a patch no major Russian oil company has wanted to bother with — is already worth a billion dollars, and is bound to be worth multiples of that. The reason, also according to RusPetro, is the brilliant technical performance of a group of American oilfield engineers. They can be trusted to manage the RusPetro miracle, they claim,because it’s a miracle they have pulled off at least once before – for Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s Yukos. The president of RusPetro doesn’t know much about oil wells, but he too comes from the miracle workers of Khodorkovsky’s Menatep Bank. And the spokesman for this company of miracle-makers is also part of the old Yukos team.

If not the ghost of Khodorkovsky, what makes the miracle believable? Sberbank has continued to lend more than $330 million to finance the dream — with collateral that sold for just $305 million, and despite breaches of loan covenants, violations of oilfield licence and concession terms, and the expiration of one of the licence terms within months.

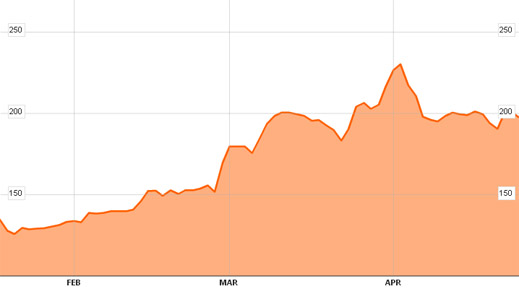

Theologians may wrestle to Kingdom Come before they will agree that a gusher of faith can be drilled out of a bedrock of reason. But in the case of oil companies taking money from investors on the London Stock Exchange this year, RusPetro (RPO:LN) is an unusually successful leap of faith. At the initial public offering (IPO) on January 18, its share price was 134 English pence. Merrill Lynch, Renaissance Capital, and Mirabaud Securities were the promoters. The current share price is 197 p, making a gain of 47%.

The current market capitalization is ₤657 million ($1,069 million). That’s for a company with a turnover in 2011 of $39 million, and a loss of $81 million. Oil production at the time of listing in January was 4,500 barrels a day.

Six month-share price chart for RPO:LN

The first disbeliever to strike a discordant note is the company auditor Price Waterhouse Coopers. At the foot of the most recent financial report, issued on April 19, this warning appears to say that the auditors are obliged to take on faith what RusPetro has told them so far. “This report, including the [auditor’s] opinion, has been prepared for and only for the Company’s members as a body in accordance with Section 34 of the Auditors and Statutory Audits of Annual and Consolidated Accounts Law of 2009 and for no other purpose. We do not, in giving this opinion, accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whose knowledge this report may come to.”

RusPetro employs the London PR firm Brunswick to relay questions and answers between the market and its managers. Asked to clarify for investors what the auditor’s warning means, the company replies: “RusPetro plc only listed on the LSE in January 2012 so the consolidated financial statements for 2011 audited by PwC are of RusPetro Holdings Limited. The disclaimer used by PWC in accounts is the standard auditors’ disclaimer. RusPetro is disclosing its 2011 financials and publishing a 2011 Annual Report despite the fact it is not under any obligation to do so in the first year of listing, as part of its commitment to transparency and disclosure.

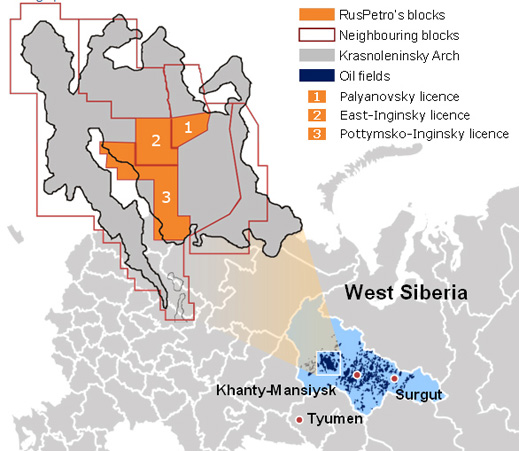

In its prospectus RusPetro reports that its current assets comprise “three contiguous exploration and production licenses covering a total area of approximately 1,205 square kilometres located in the Krasnoleninsk field in the Khantiy-Mansiysk region of Western Siberia.” The licences are called Vostochno-Inginsky and Pottynsko-Inginsky, owned by a local company called Inga; and Palyanovsky, owned by Trans-Oil. These asset vehicles are owned by RusPetro LLC, a Russian concern, which is owned in turn by RusPetro Holding Ltd in Cyprus, and sitting atop this pyramid there is RusPetro Plc.

So far, the company documents claim that Palyanovsky is the big one. But its licence expires in December of this year. The other licences have just five more years to run. If they prove to be as good as RusPetro claims, but noone in the oil business had thought likely before, RusPetro’s owners are a prime target for raiders.

Last August, the licence monitoring agency for the Ministry of Natural Resources inspected Palyanovsky and found its production levels were lower than required by its licence agreement, and it hadn’t met its prospecting obligations. The possibility that the licence may be revoked is admitted by RusPetro in the prospectus. The company adds now, three months later, “the breaches of licence conditions mentioned in the prospectus are no longer of relevance today – they referred to the drilling in 2009 (the company didn’t drill enough wells). RusPetro is now compliant with all the licence terms and all its licence commitments are satisfied in order to secure licence renewal.”

That its brand-new shareholders can be confident of retaining their asset is explained in Russian by the term,. “administrative resources”. This was conveyed to the London Listing Authority and the UK regulators this way in the prospectus: “The Russian licensing authorities have a high degree of discretion in determining the validity of a licence or whether or not licence holders are in compliance with their legal obligations.”

Here’s the leap of faith on which RusPetro’s value depends:

“The Directors believe that the Company’s key strengths are:

— large certified reserve base of 1.4 billion barrels of 2P oil and gas reserves;

— high quality oil producing assets in a contiguous licence area;

— potential for near term production growth of over 10,000 barrels of oil per day in

2012;

— advantageous location in the Krasnoleninsk field with existing infrastructure and

access to market; and

— experienced management team with expertise in developing similar assets.”

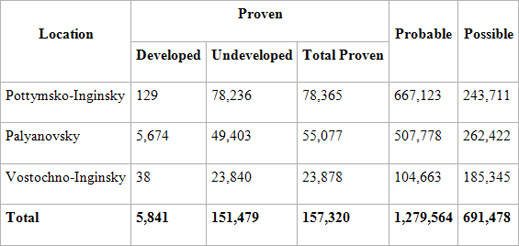

The reserve numbers are these:

They come from the US consultants, DeGolyer &MacNaughton. They are not the official reserves accepted by the Russian government’s State Reserves Committee.

RusPetro claims its reserves are approaching 2 billion barrels. But between that number and the proven reserves to date, there’s a whopping multiple of 12.5. Making up this difference requires faith in the expertise of the American engineers who have been hired to run RusPetro. Chief executive, Donald Wolcott, has written in the technical literature about how he and an American colleague, Joe Mach, taught water-injection technology to Yukos almost twenty years ago, in order to lift its oil production capacity many times over. The problem Wolcott and Mach had solved for Yukos, Wolcott has claimed, “was not damaged wells and reservoirs, but poor production and waterflood technical management. It was obvious why he [Mach] had invited me, a waterflood management expert, to Russia.”

Mach is being paid $240,000 per annum to serve on the RusPetro board as an independent. Wolcott is doing better — $1.4 million base pay, plus “a bonus of up to 150% of his base salary for exceptional performance.”

RusPetro told share-buyers in the prospectus they could rely on the company to catapult from the small reserve numbers to the big ones because “the Group has a proven track record of achieving such results by applying enhanced oil recovery technologies in a high-efficiency drilling programme.”

That’s a reference to the Yukos days. A source from the senior management of Yukos is less convinced, adding that it was Schlumberger technology the two Americans brought to Yukos, not their own, and that the production results depended on the geological conditions to which the technological innovation was applied.

A technical expert says the geology of RusPetro’s oil patch may be quite different. If he’s right, RusPetro’s market cap could collapse as soon as the size of the exaggeration is calculated by the market. This has happened in Russia before — notably at Imperial Energy’s Tomsk oilfields. At listing, RusPetro’s proven reserves were negligible, and its production forecast tiny. The valuation of the company has thus depended on ignoring this. Prospectors and drillers in the same area, with similar well geology, have reported the phenomenon that wells may start flowing profusely, but within months or years they can tail off to nothing.

RusPetro admits in the risk section of the prospectus that “current reserves and forward production data are only estimates and are inherently uncertain; the Group’s total reserves may decline in the future and the Group may not achieve estimated production levels. Special uncertainties exist with respect to prospective resources.”

Other specialists say the lack of state-certified reserve numbers, and the size of the gap between DeGolyer & McNaughton’s projection and domestic assessments are indicators of risk which the market has yet to notice. Wolcott was asked: “What are the reserves according to the Russian classification scheme (A,B,C1,C2), and what reserves according to that scheme have been registered officially with the State Reserves Committee?” He replied: “RusPetro’s reserves are measured and reported according to international standards, due to its listing in London and its international investor base who all rely on these standards. DeGolyer & MacNaughton who conducted RusPetro’s reserves audit is a reputable international reserves audit specialist. According to international standards, RusPetro’s oil reserves currently are: 173 million barrels in 1P reserves and 1,545 million barrels in 2P reserves, as reported in it 2011 results announcement on 19 April.”

The State Reserves Committee was asked whether RusPetro has registered a reserve figure that has been approved by the Committee, or whether an application is pending. The Committee deferred answering, and passed the question to the Ministry of Natural Resources, which passed it to the licensing agency, Rosnedra. It appears there is no official government confirmation of RusPetro’s reserves.

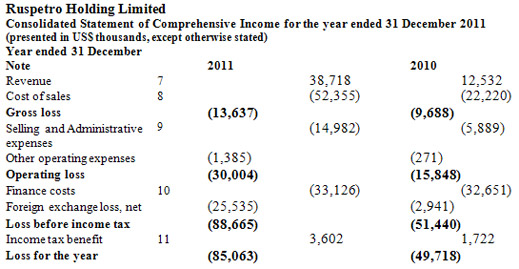

If this makes the assets underground doubtful, the financial picture above ground isn’t encouraging. According to this month’s financial report, the company is seriously in the red:

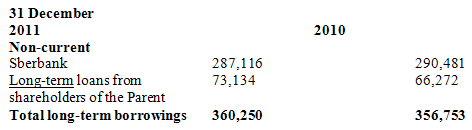

With $360 million in current borrowings, the company’s asset balance is negative. “In accordance with the legal framework in the Russian Federation, creditors and tax authorities may initiate bankruptcy procedure against an entity with negative net assets. RusPetro, INGA and Trans-oil reported net liabilities under Russian GAAP at 31 December 2011 and 2010. However, no such bankruptcy procedures have been initiated either by the creditors or the tax authorities against then. The Directors consider their net liability position to be normal given that the companies are still at a development stage.”

What appears to be happening is that the Russian owners of RusPetro and Sberbank are holding the company up, using their influence to prevent the revocation of licences, bankruptcy sanctions, or foreclosure of loans. While there is considerable detail on the history of the special vehicle sales and purchases that preceded the IPO in January, it is far from clear which of these Russians and their offshore entities control the company — Vladimir Marchenko (Crossmead), Andrei Likhachev (Limolines), Andrei Rappaport (Makayla), and Alexander Chistyakov (Nervent, Bristol Technologies). Nor is it clear how much of a stake in the company shareholding is held independently of the Russians by Wolcott (Wind River Management, Bolton Nominees), Thomas Reed (Nervent), the chief financial officer, and James Gerson (Limolines), an Englishman in a St.Petersburg advisory company called Lonburg.

Gerson is identified as an associate of Likhachev in the Limolines stakeholder, but this prospectus note doesn’t make clear what their respective stakes in RusPetro actually are. “Limolines is owned as to 50% by Inderbit Investments, a company incorporated in the Republic of Panama, whose sole beneficial owner is Andrey Nikolayevich Likhachev, and as to 50% by Conchetta Consultants Limited, a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands and controlled by Altera Investment Fund SICAV-SIF, an investment fund supervised by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier in Luxembourg. James Gerson, a director of the Company, is a consultant to Limolines Transport Limited and is deemed to be beneficially interested in such shares.”

Likhachev has served on the Russian state privatization committee, and in May 2010 was appointed Deputy CEO of Oleg Deripaska’s energy assets in EN+ and board chairman of Eurosibenergo. He’s still there.

Wolcott has been associated with Chistyakov in the Yukos past; they are umbilically joined this time through a web of offshore entities. “Don Wolcott, a director of the Company, owns 100% of Wind River Management Limited and is deemed to be beneficially interested in such shares. On 22 January 2010, Bolton Nominees Limited, the sole legal and beneficial owner of Wind River Management Limited (‘‘WRM’’) and controlled by Donald Wolcott, granted Bristol Technologies Limited, a company owned and controlled as to 100% by Alexander Chistyakov, a call option to acquire 50% of the issued share capital of WRM.”

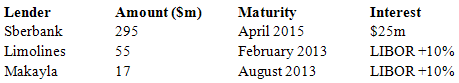

Then there is Andrei Rapaport (aka Andre Rappaport) who appears to have bought out the debt owed by RusPetro to the original owner of its oilfield licences, Itera, and whose credit to RusPetro shows on the current balance sheet as a loan of $17 million from Rapaport’s vehicle, Makayla:

This is how RusPetro identified its creditors in the corporate presentation this month:

And this is the short and long-term borrowings picture from the financial report for the end of last year:

The prospectus claims: “Andre Rappaport owns 100% of Makayla Investments Limited (‘‘Makayla’’). Pursuant to the acquisition of the Itera Debt by Makayla on 13 December 2011 and the agreement with the Company dated 16 January 2012 to convert the Itera Debt into Ordinary Shares in consideration for the issue of Ordinary Shares worth approximately US$26.1 million at the Offer Price, the number of shares to be held by Makayla at Admission will increase by such number of shares. See paragraph 3.3 of Part 9 ‘‘Principal Shareholders and Related Party Transactions’’ for further details. Additionally, on 16 January 2012 Makayla entered into a put option agreement with Nervent pursuant to which Makayla may require Nervent to acquire two-thirds of the Ordinary Shares to be issued to Makayla pursuant to the conversion of the Itera Debt in June 2012 thereby reducing Makayla’s interests in the Ordinary Shares.”

Ruspetro was asked to unravel these complications, and say if the company would clarify exactly which of these Russians and non-Russians own what sized stakes in the company. The reply repeats the prospectus language, adding that “Andrei Likhachev does not hold any shares directly but is considered beneficiary as per above.”

On background, the company is claiming there is no control group. But that appears to be mean there is no single control shareholder, not that the Russians don’t form a group with their American hires. If there is a single hidden hand, the prospectus implies it is Likhachev’s. “Limolines will be a substantial shareholder of, a ‘‘person exercising significant influence’’ over, and a ‘‘related party’’ to, the Company for the purposes of the Listing Rules” (page 87).

In an investor presentation in mid-April, RusPetro claimed that as of March 31 it has a free float of 40%. This isn’t quite accurate. Related parties, including Limolines, Makayla, and Sberbank, controlled 66.9% ahead of the prospectus, with Henderson Global Investors, Schroders and GLG holding 17.4%. After the IPO, as of March 31, shareholders termed “other” comprise 20.3%. Schroders holds 4.7%, and Henderson 8.9%, i.e., a free float of 33.9%. Ruspetro was asked to clarify the positions of Likhachev, Rapaport, Chistyakov, and Marchenko? Ruspetro insists the free float adds up to 40%. It won’t clarify the position of Likhachev.

The shareholder identifications in the prospectus stop short of explaining how it can happen that Sberbank, and its Sberbank Capital unit, have been so generous with cash, and so insouciant when it comes to enforcing its loan terms and covenants. The bank took 20% of the IPO proceeds to cover past-due interest and a portion of principal. Sberbank also took a 5% stake in RusPetro before the IPO; 3.1% afterwards. Are there other relationships between Sberbank and RusPetro, which may not be required for disclosure to the London Stock Exchange or UK regulators, but are obligatory under Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s December 28, 2011, beneficial ownership disclosure decree?

What is the collateral securing RusPetro’s borrowings and lines of credit from Sberbank? The prospectus reported that “the Parent [RusPetro Plc] has pledged all its shares in INGA and Trans-oil and Trans-oil’ promissory notes as part of the terms of the credit facility.” What then protects the exposure of the dominant shareholders in the Parent, and lenders of another $74 million?

In this warning from the risk section of the prospectus, there is an unusual, if implied reference to the sensitivity of the relationships which the Americans and Englishmen at RusPetro may have regarding Sberbank, as well as Russian state officials with whom the company interacts: “The Company is subject to the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Bribery Act.”

Of course, RusPetro is subject to these statutes, not to mention the Russian anti-bribery laws too. That usually goes without saying.

Leave a Reply