By John Helmer, Moscow

The outflow of private and corporate capital from Russia is accelerating.

Pressured by the cutoff of incoming investment and bank loans, the closure of Russian depositor bank accounts in Europe, and the threat of asset confiscation in the UK – all ordered by US sanctions with threats of more to come — the loss of domestic investment funds continues, undeterred, to squeeze the Russian economy. That is exactly the US war aim.

In the history of warfare against Russia, defending by retreating has been tried before, though this isn’t what Russian capital is doing this time.

According to the latest Central Bank of Russia (CBR) report, in the ten months of this year to October 31, the total outflow was $42.2 billion. That compares to $14 billion in the same period last year, a threefold increase. This is also the largest volume since the record year of 2014, the start of the US war, when outflow reached $152 billion; and in 2008, the year of the oil and commodity price collapse, when the outflow was $137 billion.

The month of October figure for outflow was $10.3 billion, according to the latest CBR report. This indicates even faster acceleration; the aggregate outflow to September was $31.9 billion – a monthly average of $3.5 billion.

The Central Bank’s explanation is that the increase is nothing exceptional: “it has been shaped approximately in equal proportions by banks’ transactions to extinguish external liabilities and those by other sectors to acquire financial assets abroad.”

The good news, according to some analyses, is that because the oil price has been rising sharply and the size of Russia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in parallel, the outflow is dwindling as a proportion of GDP — from almost 13% in 2014 to about 4% this year.

GDP growth, however, recorded a retreat in October – from 1.9% annualized rate in September to 1.3% in October. The lower figure is now the government’s revised forecast for next year, with an even lower one for the first quarter of 2019.

A report last week by the chief economist for Vnesheconombank (VEB), the state bailout bank, is not so sanguine. “If we look at the dynamics of the rouble… and the separation from the dynamics of oil prices, it is also due, not to the fact that this dependence of the economy on oil prices has disappeared, but to the fact that almost all the gain between the current price of about $70 per barrel and the fact that it was oriented earlier, at the beginning of the year, to $50 plus, went into outflow of capital. In fact, almost nothing remained inside the economy; there has even been something of a reduction.”

According to Andrei Klepach of VEB, it is proving impossible for the state, through state budget spending or by commercial and state bank lending, to convert export earnings, which have been rising because of oil, into domestic economic growth, which has been shrinking towards the 1% mark. “The fact that we sterilize and remove from the economy virtually all [income from higher oil prices], that a significant part of the income growth associated with higher oil prices [according to the federal budget rule], is not always good. It is good, maybe, for ratings – for budget stability and the stability of the [government’s policy]. But in terms of economic growth, [outflow of capital] is one of the main reasons why we are growing almost twice as slowly as countries with a comparable level of income.”

The Russian reason, Klepach said, is fear of war, fear for the future.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and other international organizations have reported their calculations of Russian capital outflow, including both the official Central Bank figures and also what the IMF counts as “hot money”. In total since 1992, the sum is more than a trillion dollars.

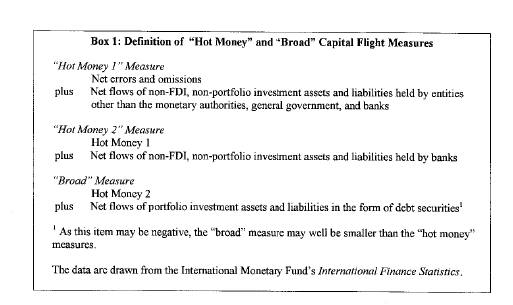

The IMF defines hot money as a combination of the official CBR data and the category of money identified in CBR statistics as “errors and omissions”.

Source: https://www.imf.org/en/

In the IMF’s calculation, Russia is the only example of an economy in the world in which domestic economic growth fails to reverse capital outflow, and to attract capital to return. Privatization in Russia is also unique because it has accelerated the rate of outflow of domestic funds, enlarging the gap between domestic outflow and foreign inflow.

Hot money is not the same as dirty money. Western journalists and think-tank specialists try to obfuscate the difference between small-scale mafia gangs specializing in their usual trade — drugs, prostitution, extortion – and the much bigger bank robbers who operate from inside the banks themselves, borrowing from the Central Bank and then lending to themselves through dozens of entities which have no intention of repaying the money. In that process, the British Government has connived by granting political asylum to robbers on the run.

Boris Berezovsky and Mikhail Khodorkovsky are the best known of them. Andrei Borodin, the accused fraudster who looted the Bank of Moscow, is another Sergei Pugachev is even more notorious because he has been defended by the Financial Times and other London media as a political opponent of President Vladimir Putin.

Even without grants of asylum, those who have been charged by the Russian prosecutor-general with fraud, embezzlement and other financial crimes continue to be relieved by the London courts on the ground that the charges are politically motivated, or that the accused couldn’t face a fair trial from potentially corrupt Russian judges. This applied, for example, to the September case of Ilya Yurov, the Trust Bank owner – and three months earlier, the case of Andrei Votinov.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has cautioned against equating Russian capital outflow with money laundering. “At the respectable, legal and (privately as well as socially) beneficial end of the spectrum, we find capital outflows motivated by portfolio versification and similar risk-sharingconsiderations. The sources of the funds are legitimate; their transfer abroad is in accordance with the law; and neither tax evasion nor tax avoidance is an issue.”

“At the other extreme of the spectrum we find capital outflows representing the transfer abroad (and out of reach of domestic law enforcement and national tax administrations) of illegally acquired income or assets. Money laundering – transforming illegal earnings and assets into legal earnings and assets – is an old, established global industry that has only recently prompted a coordinated global response by law enforcement, financial regulators and supervisors, and the international financial institutions (IFIs).”

“Somewhere in the middle of the spectrum we find capital outflows representing the transfer abroad of legal, legitimately acquired income or assets, motivated by the desire to escape either the legitimate domestic tax authorities and/or the predatory attentions of corrupt and confiscatory agents of the state – central, regional or municipal – or of the criminal community.”

“Not only is capital flight a fuzzy concept, it is also highly emotionally charged. The view prevailing in the media is that capital flight is something verging on the criminal, if not outright criminal. The combination of the phrases ‘capital flight’ and ‘money laundering’ fits in well with this conventional wisdom.”

In the flight of one trillion dollars of Russian capital since 1992, have the assets created a new class of Russians? does it have an ideology and a political programme for Russia’s future? On which side in the present war does it stand?

Elisabeth Schimpfossl’s book of interviews of the Russian rich in London reports that among the conditions of access her interviewees insisted on, one was the refusal to explain how their fortunes had been earned; the other was to discuss what future they see for themselves and for the country. For more details, read this. Notwithstanding, Schimpfossl’s sample demonstrates no intention of returning their capital, themselves, their children, or even their art collections and other toys to Russia. For them there is no deterrent in the intensification of Russia hatred in the Anglo-American media.

Leave a Reply