By John Helmer, Moscow

The Routledge Handbook of Russian Foreign Policy is a 450-page compendium by academics who earn modest livings in think-tanks at places in North America or Europe like Louisville, Hamburg, San Francisco, Rhode Island, Edinburgh, West Virginia, South Carolina, Southern California, Newcastle, Uppsala, Tartu, and Helsinki. In the book Russian academics in Russia are outnumbered by the westerners by 26 to 8; all are on small state-paid livings led by Andrei Sushenkov, programme director at the Valdai Discussion Club. That 14-year old think-tank is financed by the Kremlin information chief Alexander Gromov and the president’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov.

The handbook proprietor, once a well-known 19th century London publisher, is now the US conglomerate Informa. It operates on the principle of Gresham’s Law – the more information you produce for sale, the less likelihood you will be outsold by the truth. The Valdai Discussion Club and other think-tank creations in Moscow have been described by President Vladimir Putin as a “propaganda machine” to compete with their Anglo-American counterparts. To a Kremlin sponsored journalist, their output is “political marijuana smoke.”

The handbook writers must be approaching retirement because they dedicate their work “to the younger generation of scholars of Russian foreign policy”. The book begins: “The importance of studying Russian foreign policy (RFP) today is as great as ever.” By page 450 this is neither more obvious, nor less.

For the next sixty days, the book can be read for free at this link.

Otherwise, the paper version will cost you more than three hundred dollars.

There is an important difference between the Russian contributors who live and work in Russia and the westerners; that’s to say those, whether of Russian origin or not, who make their livings in institutions in the US or on NATO territory which are financed directly or indirectly by the US Government and US foundation grants.

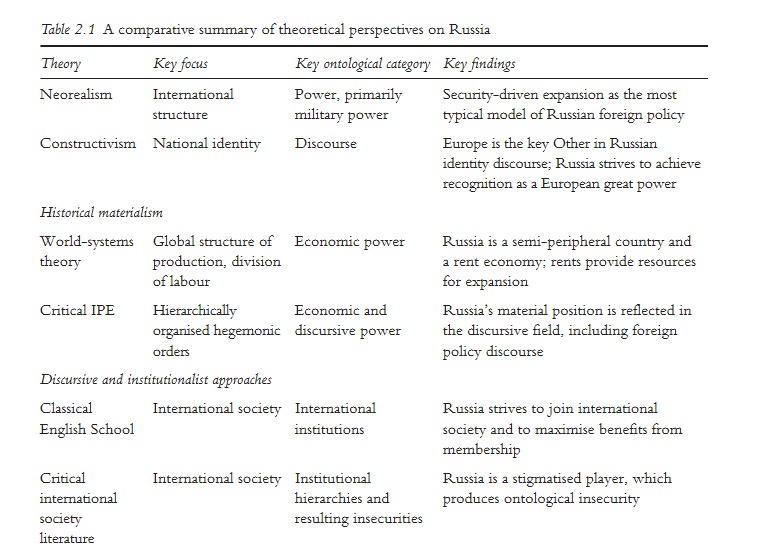

The latter report in their footnotes never having studied Russian press reports of foreign policymaking as it happened nor interviewed a living Russian soul engaged in it. Instead, they rely on each other, reporting as evidence for their claims works by professors who are their patrons for publications, research grants, and promotions to tenure. To identify admission to this self-referential network, the handbook presents this list of passwords:

READY RECKONER OF ACADEMIC JARGON ABOUT RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY

KEY: IPE is an acronym standing for international political economy. “Othering” has meaning inside the US for something outside. But if the word is used outside the US noone can know what it means. Source: https://www.readcube.com/

Sentries are on duty throughout the handbook. If on challenge you don’t say the password, you don’t qualify for understanding what is being said. You also miss lunch at the club table. The Valdai Club, for example, provides business-class airfares and five-star resort accommodation for its password-authorized guests. These include men known to the Kremlin to be espionage agents for the US military.

The passwords open to texts of circular reasoning which conclude what must be proved without being disturbed by the possibility of contrary evidence. For example, John Berryman of London, who starts and ends on the proposition that Russia is a congenital troublemaker: “Generating security concerns among the sixteen states which enjoy common borders with the Russian Federation, Russia’s open challenge to the post-Cold War and post-Soviet settlement in Europe has triggered something of a ‘New Cold War’.” Or Charles Ziegler of Louisville: “There is a close link between Russian foreign policy and domestic policy… the Crimean episode [w]as an extension of these domestic tactics…to boost Putin’s flailing popularity.” Or Mikhail Strokan of Philadelphia and Brian Taylor of Syracuse (New York): “Under Putin most analysts maintain that the FSB [Federal Security Service] has significant influence in terms of providing information and analysis… Perhaps the most controversial and spectacular assassination linked to the Russian security services was the murder of former FSB officer Alexandr Litvinenko…”

Left to right: Prof. John Berryman, Prof. Charles Ziegler; Prof. Brian Taylor.

Julien Nocetti of Paris (France) achieves his Quod Erat Demonstrandum at the beginning of his chapter to the handbook, so repeating it at the conclusion was easy-peasy. “The official Russian narrative and policy cannot but hide an ultimate goal which appears close to what has been described as cyber power… Overall, Russian interference in the US election perfectly illustrated how the Russians view cyber, i.e., as an embedded part of the broader concept of information operations.”

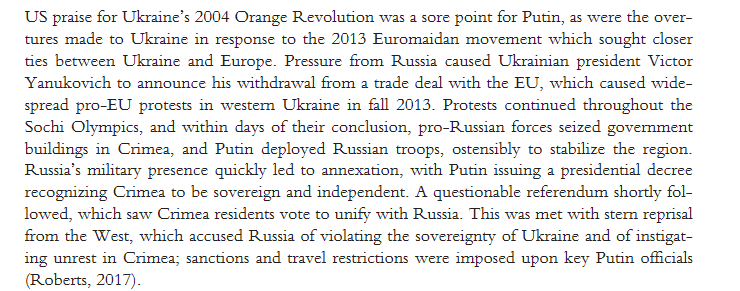

On the events in Ukraine of February 2014 Kari Roberts of Mount Royal University in Canada explains that what must be proved can be assumed:

Yuval Weber — in Washington on study leave from his post at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow — demonstrates that the difference between the Anglo-American approach and the native Russian one is a handful of facts, and the remuneration – not to say intellectual honesty — to see them, and not to see them, for what they are. Reviewing case studies of energy policymaking by Soviet and Russian officials, Weber concludes that “energy revenues do not make Russia immediately more aggressive in terms of militarized interstate disputes… this contrasts with the conventional wisdom of Russian foreign policy and energy, which often draws a direct and mechanical link from oil booms and busts to more, or less, conflict abroad.”

Other Russian contributors to the handbook also tell tales of Russian foreign policymaking from multiple records of what happened. This leads them to conclusions which are the opposite of the western academic reports. For instance, Valery Konyshev and Alexander Sergunin of St. Petersburg: “the military’s role in Russian foreign policy is quite limited: the use of military force is seen as a last resort, when other — non-military means — are exhausted, and it is done in a rather limited/restricted way… As Putin enjoys stable domestic support, the MoD’s [Ministry of Defence] impact on decision-making could rise only as a result of a decline in relations between Russia and the West…Moscow has used just enough military force to achieve policy goals, but not more. Coercion was conducted by degree, in measured doses.”

According to the current salary schedule for Russian academics, Konyshev and Sergunin get paid about Rb30,000 ($500) per month for work like this; their Anglo-American counterparts are paid on average $8,500. Obviously, there’s more money in the Anglo-American line. A handbook on the resistance of Russian intellectuals to the earnings differential doesn’t run to 450 pages.

The geography of the Routledge handbook is eccentric. The Arctic region receives a chapter to itself, as do the European Union, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Missing is all of Africa, including the Maghreb and the sub-Saharan regions; the Americas south of the Rio Grande; Southeast Asia; the Balkans, Greece, Cyprus and Turkey.

The reality test of such a compendium, the money shot, is the index. That’s where the expert on how and why Russian policy is decided will find the names of those who concentrate and exercise the greatest power in the Putin Administration. The word oligarch isn’t in the index at all, though it is mentioned at page 109 as the principal reason for Putin’s promotion from obscurity to presidency. He was, according to Weber, “a compromise candidate between Yeltsin’s ruling clique and the oligarchs who had grown wealthy and powerful in the preceding decade, a modest individual dwarfed by the bureaucratic challenges of running Russia.” Dwarfed – brave of Weber to use such a word in this context. But he ought to know better than to describe the challenges of running Russia as primarily bureaucratic ones.

What Weber is wise enough not to say is betrayed by another Russian contributor, Artyom Lukin (right)  of the Far Eastern Federal University in Vladivostok. “As always,” Lukin concludes, “Moscow’s main game is political rather than economic”. That’s preposterous; but even if it weren’t, it’s not a hypothesis which Lukin or anyone else in the handbook judges worthy of being tested.

of the Far Eastern Federal University in Vladivostok. “As always,” Lukin concludes, “Moscow’s main game is political rather than economic”. That’s preposterous; but even if it weren’t, it’s not a hypothesis which Lukin or anyone else in the handbook judges worthy of being tested.

The evidence can be found in what is missing from the handbook index. The name of Igor Sechin (Rosneft) is mentioned in passing just once; Alexei Miller (Gazprom) not at all. The names which have directed Russian policy projection all over the globe, men who have kept the Foreign Ministry diplomats in private cash and comfort, are Oleg Deripaska, Alisher Usmanov, Mikhail Fridman, Anatoly Chubais, Victor Rashnikov, Mikhail Prokhorov, Victor Vekselberg et al.

A handbook of Russian foreign policy which doesn’t mention their names is a walking-stick for the blind.

Leave a Reply