By Simon Hewitt, Geneva*

AN AUCTION staged in Paris this March has written another unedifying chapter in the art market history of the Russian Avant-Garde.

On April 19 John Helmer alerted me to an article on his blog Dances With Bears, long-windedly entitled (and I have abbreviated it) Is The Market for Russian Art Forgery Better Value than the Market for the Genuine Article? ‘Suspicious canvases are surfacing regularly in all the European capitals’ wrote Helmer.

Hardly news, but what caught my eye was a paragraph halfway down, where he reported that Tajan, a mid-ranking Paris auction firm, had refused to answer his questions about their recent sale of Avant-Garde works – or about the little-known ‘expert’ Alexandre Arzamastsev who had guaranteed their authenticity.

The 61-lot sale was entitled Impressionist & Modern Art and took place at Tajan’s premises near Gare St-Lazare on the evening of Tuesday 8 March 2016.

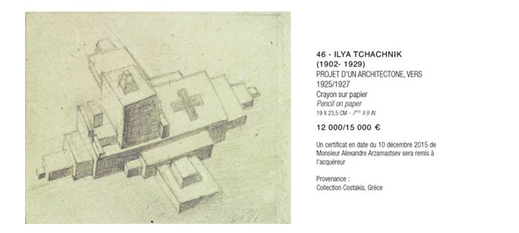

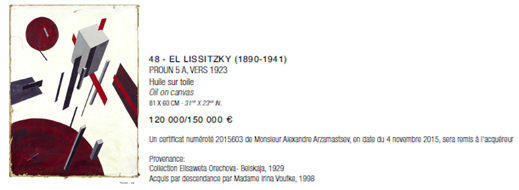

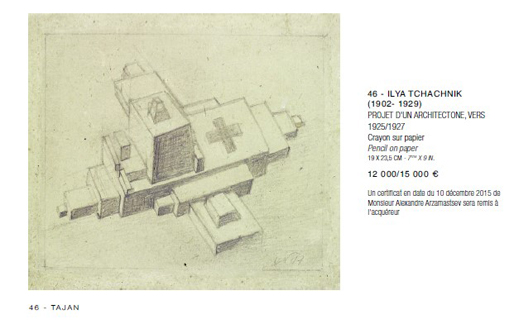

The catalogue featured six works assigned to Russian Avant-Garde artists: three drawings, by Ilya Chashnik (Project for an Architecton), Nikolai Suetin (Red Architecture) and Ivan Klyun (Suprematist Composition); and three paintings – Chashnik’s Suprematist Cross, El Lissitzky’s Proun 5A and Lyubov Popova’s Suprematist Construction. Authenticity certificates were provided by Mr Arzamastsev for the Suetin, both Chashniks and the El Lissitzky. According to the price-list posted on the Tajan website, only the El Lissitzky sold.

On April 12 Helmer e-mailed Caroline Cohn, Senior Specialist in Tajan’s Modern Art Department, asking for more information about the Chashniks, the El Lissitzky and expert Arzamastev.

Cohn replied (in English) promptly but evasively, merely noting that the works in question ‘have been sold on March, the 8th,’ adding: ‘We don’t have any other artworks by this artist (sic) for the moment.’ Next day Helmer tried in vain to call Cohn, before e-mailing her to ask about the provenance of the works. He again requested information on Arzamastev as ‘there is no recognition in Moscow of the name of your expert.’ Cohn did not reply.

Two days later, on April 15, Helmer e-mailed her again, asking her to clarify whether both works had indeed been sold as she had told him; results published on the Tajan website indicated that the Chashniks had not. (Did Cohn mislead Helmer, or did her limited grasp of English promote confusion? In colloquial French auctionspeak, vendu can mean either ‘sold’ or ‘offered for sale.’) Again Helmer received no reply.

Helmer’s article appeared on-line on April 18. Next day he sent it to Cohn – copying in Jean-Jacques Wattel, Tajan’s Directeur des Départements (Head of Auctions), offering tocorrect any ‘error of fact or interpretation’ they might find in it. ‘Your refusal to respond to questions by telephone and e-mail was regrettable’ commented Helmer.

Cohn replied tersely on April 20 that she had ‘just come back today from Italy for our expertise days and I discover your messages’ (it appears, bizarrely in this age of themobile-phone and laptop-computer, that Tajan staff are unable to access their e-mails unless they are ensconced behind their desks).

Helmer responded promptly, noted the absence of any objection, and informed Cohn he was working on a follow-up article ‘because questions have been raised in Moscow about the drawing by Chashnik you report in your March 8 catalogue as having come from the Costakis Collection in Athens.’

The Tajan Catalogue entry for Lot 46, the Chashnik drawing, April 21, 2016

When, he asked, had the Costakis Collection consigned the drawing for sale – and why was a certificate by Mr Arzamastsev considered necessary in this case?

He stressed that ‘non-reply, if you choose it, will be reported as your refusal to reply. In a matter as sensitive as this, you and your management will appreciate how the market will interpret that.’

Cohn was rattled. ‘The tone which you use is totally discourteous’ she admonished him – before passing the buck rather than reply to Helmer’s questions on provenance. ‘I am not the expert but a collaborator of the modern art department of Tajan,’ she reminded him. ‘I send your letters to the Expert, Mr Arzamastsev and ask him to answer you.’ Mr Arzamastsev did not answer Mr Helmer.

Meanwhile Cohn’s superior, Jean-Jacques Wattel, imitated her It Ain’t Me Guv line of selfdefence by informing Helmer that ‘Many people in Tajan is taking care of your requests. I’m not in charge with such files.’

Helmer responded to Cohn’s accusation of discourtesy by explaining that ‘You are being asked to show that you and Tajan have not been trying to sell faked artworks by Chashnik. Courtesy is in the extension of an opportunity to reply. You received the courtesy, and you declined the opportunity.’

Helmer’s follow-up article went on-line a few hours later, entitled Tajan Auction House Exposed in Fake Sale Claim for Russian Avant-Gardist Ilya Chashnik. It began: ‘A rare drawing by Ilya Chashnik, a Russian artist who died in St Petersburg in 1929, was sold last month by the Tajan art auction house after a warning that the provenance claimed for the work was false.’ After reading his April 18 article, reported Helmer, ‘experts on Chashnik’s circle of artists and on Chashnik himself have responded that they doubt the authenticity of both Chashnik pieces’ in the sale.

Tajan’s expert, he continued, had ‘refused to respond to questions to identify himself, clarify his expertise, and confirm the published claims about the Chashniks.’ Then Helmer fired a bombshell – revealing that Costakis’s daughter Aliki had informed Tajan before the sale that the Costakis provenance given for the Chashnik drawing (shown left) was bogus. ‘This work came to our notice before the auction,’ acknowledged Maria Tsantsanglou, Head of the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Salonica, which houses the Costakis Collection. ‘Such a work never belonged to the Costakis Collection. This was a false provenance.’ On March 5 Aliki Kostaki, the collector’s daughter, had written to Tajan as follows: ‘It has come to my attention that on March 8 your company will auction lot n° 46, Ilya Tchachnik Projet d’un Architectone, provenance of which is attributed to Costakis Collection, Athens. I have to inform you that this particular piece never belonged to my late father’s collection. I demand that you remove the false provenance asap and send me written documentation which proves the above. Otherwise I will take legal actions against your company.’

Tajan did not reply.

The State Museum’s 2014 show: “The Costakis collection and the Russian avant-garde. 100 years since the collector’s birth”

Shortly before publishing his follow-up in April 21, Helmer had advised Wattel and Cohn he had ‘confirmation that the drawing was never in the Costakis Collection’ and that, even though Tajan had been ‘warned of this from Greece and told to remove the claim or face litigation for fraud,’ their website ‘to this day shows you are continuing to perpetrate the falsehood.’ Helmer invited them to ‘explain the circumstances of the false provenance and what appears to be the false certificate by your expert, Mr Arzamastsev.’ Helmer received no reply.

Costakis’s daughter was not alone in voicing her concern to Tajan in the run-up to the sale.

On March 4 James Butterwick (right) wrote to Caroline Cohn requesting information about the provenance of the paintings ascribed to Chashnik (right) and El Lissitzky. Cohn informed Butterwick that the lots had been consigned by a ‘French art dealer’ who had bought them from a late American journalist who ‘knew the artist’ (sic). By using the singular, Cohn was presumably referring to El Lissitzky. ‘An American who knew the artist?’ retorted Butterwick incredulously (El Lissitzky died in1940 and is not known to have visited America). ‘How is that possible? Who exactly and between what dates?’

‘I don’t have the dates’ answered Cohn, adding that both works came with ‘a certificate from Mr Alexandre Arzamastsevwho is preparing the catalogue raisonné of El Lissitzky and knows this artist very well.’ ‘Is Mr Arzamastev recognised by Sotheby’s and Christie’s?’ asked Butterwick. ‘I don’t know the politics of our competitors’ retorted Cohn. ‘If you would like to make some searches on internet, you will find that Mr Alexandre Arzamastsev is well known. If you have doubts, don’t bid. I can’t provide you more information than what you will find in the catalogue.’

‘I would have thought, as the seller of these paintings, you would want to be 100% sure of their authenticity’ mused Butterwick. ‘Do you provide this guarantee?’ ‘We are sure of the authenticity’ reiterated Cohn. ‘Mr Alexandre Arzamastsev the expert guarantees the authenticity. That is enough for us. Would you like to be register to bid by phone?’

‘My opinion does not coincide with that of Mr Arzamastsev’ retorted Butterwick. ‘I will not be registering, thank you.’

Arzamastsev’s certificate for the El Lissitzky was dated 4 November 2015 and numbered 2015-03, suggesting it was only the third certificate issued by Arzamastsev in the first ten months of last year. Strangely, though, it was numbered 2015603 in the Tajan catalogue, making it look as if he had delivered over 600.

The catalogue estimate was €120,000-150,000. Butterwick told me he had seen no paintings by El Lissitzky on the global market for the last 15 years, and ‘an El Lissitzky with full provenance and exhibition history of a similar size would cost €5-6 million, even in today’s depressed market.’ Tajan sold their El Lissitzky for €115,200.

Source: Tajan catalogue, http://www.tajan.com/pdf/2016/Ventes/1628.pdf

Mr Arzamastsev’s certificate for the Chashnik Suprematist Composition with Cross was even more interesting. Like the other certificate it was written in French on Arzamatsev’s letterhead paper, giving his address as 36 avenue Jean-Moulin, 75014 Paris. No one named Arzamatsev appears at this or any other address in the Paris phone-book – either in the pages jaunes (for individuals) or pages blanches (for professionals) – so Arzamatsev is presumably ex-directory: a curious approach for someone offering his services as an independent expert.

The certificate (right) is dated 10.02.2016 and numbered 2016-01. Its very first sentence contains no fewer than four schoolboy spelling-errors (sousigné for soussigné, sertifie for certifie, oevre for oeuvre and colobarateur for collaborateur). One accepts that Mr Artamastsev may struggle with his French (despite appearing to be a long-standing Paris resident), but issuing official certificates without having them checked for linguistic error by a native-speaker seems alarmingly unprofessional. For Tajan to blindly accept such sloppily-written certificates as guaranteeing the authenticity of expensive artworks is mind-boggling. When I submitted this ‘sertificate’ to an experienced Paris lawyer, I was informed that the French judicial system considers that ‘the law is not for imbeciles’ – i.e. a rash of spelling mistakes should incite caution amongst those for whom such documents are intended, and ‘may serve as a warning of possible fraud.’

The certificate dates the Chasnik painting to circa 1924 but, oddly, no date was mentioned in the Tajan catalogue. The estimate was €18,000-20,000. Mouth-watering! Ilya Chashnik (1902-29) died in Leningrad from peritonitis at the age of 26. Only five oil paintings by him are known. Three are in Moscow (Tretaykov Gallery), one in Salonica (Costakis Collection), and one in Madrid (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza). The painting offered by Tajan was, at 35 x 22cm, far smaller than any of these, but the market-price for such a rare Suprematist oil would, says James Butterwick, be in the region of €2 million – about one hundred times more than Tajan appeared to be expecting.

What was the rationale behind Arzamastsev’s estimate? We are not talking about some little old lady stumbling across the picture in a musty attic and, through blissful ignorance of its market value, being happy to sell it whatever the price. Caroline Cohn told Butterwick the Chashnik painting was consigned by a Paris art dealer – someone hardly likely to be so naïve as to think a rare Suprematist oil worth a measly €20,000. It did not sell. Neither did the Chashnik drawing, to which Arzamastsev assigned an estimate of €12,000-15,000. James Butterwick presented a Chashnik drawing of similar dimensions at TEFAF Maasticht in 2015 – priced €150,000.

I decided to take up Caroline Cohn’s invitation to ‘make some searches on internet’ to ascertain just how well-known Monsieur Arzamastsev actually was. I googled him in French, English and Cyrillic.

French googling threw up a Linked-In entry for a photo-less Alexandre Arzamastsev ‘from the Paris area’ described as a художник [artist] rather than an expert. This seemed to be Tajan’s man though, in the absence of further information, it was hard to be sure. There was also a Google link to Arzamastsev’s involvement in another Paris sale six years earlier, as issuer of a certificate authenticating an El Lissitzky drawing from the ‘Collection of Monsieur S.’ auctioned by David Nordmann on 26 March 2010. This certificate was dated 10 April 2002 – eight years before the sale. The drawing, in gouacheand pencil, was entitled La Ville (‘City’) and dated c.1920. Its estimate was €40,000- 50,000. It was unsold.

The highest-ranking Alexander Arzamastsev identified by English googling was the Head of Computer Simulation at Tambov University, followed by a drummer in the endearingly-named Russian rock-band Bering Strait. Google also threw up 24 facebook Alexander Arzamastsevs – none of them art experts. Tajan’s Alexander Arzamastsev did not even make it on to the English Google Search front-page.

I had to click on page 2, and scroll down to entry 13 – past the Alexander Arzamastsev who plays ice hockey for Akuly Sakhalin (‘Pride of the Pacific’) – to find a fleeting reference to Tajan’s Alexander Arzamastsev, this time described as a ‘Moscow art historian’ in a 2012 article by Patricia Railing, head of InCoRM (International Chamber of Russian Modernism).

Tajan’s Alexander Arzamastsev did not crop up again until Google entry #30: a link to a sale at Dreweatts & Bloomsbury in London back in June 2006, when he confirmed the authenticity of an El Lissitzky painting (estimate £220,000-280,000). It was unsold. I tried googling Alexander Arzamastsev art expert instead, but found no further information – although entry #9 looked promising. It was a link to the site of the Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en OEuvres d’Art (French Art Experts Association), so I clicked on it eagerly. In vain: no Alexandre Arzamastsev is listed among its members.

Googling in Cyrillic thew up nothing about Tajan’s Александр Арзамасцев whatsoever (though I have to admit I gave up after the first 50 links). A Dr Alexander Pavlovich Arzamastsev was near the top of the list, but he was a late, lamented pharmaceutical boffin (an Academician and ‘Honoured Worker of Science’ to boot).

It is not, of course, the fault of Tajan’s Mr Arzamastsev that cyberspace is polluted by eponymous drummers, hockey-players, dead chemics and computer simulation specialists but, if you are looking to ascertain his track record as an art expert, Internet is not the place to look – whatever Tajan personnel may airly suggest.

So I contacted my Moscow-based colleague Sophia Kishkovsky from the Russian edition of The Art Newspaper. ‘I have not heard of Arzamastsev’ she replied bluntly. But Sophia kindly tracked down a 2010 article in Komsomolskaya Pravda, in which art collector Leonid Sachs stated that Mr Arzamastsev had discovered that the Avant-Garde artists Lyubov Popova and Nadezhda Udaltsova ‘bought paint from the same shop in Europe.’

Mr Sachs owns a picture by each artist. Given that chemical analysis has revealed that both works contain paint squeezed from the same tube, he has every reason to be grateful for Mr Arzamastsev’s discovery.

On April 21 I wrote to Caroline Cohn’s immediate superior Anne Perret, Director of Tajan’s Modern Art Department, asking for the e-mail address of Monsieur Arzamastsev so that I could seek his reaction to Helmer’s article. Madame Perret did not reply. But five days later, on April 26, I received an anonymous e-mail with no covering message, sent from the grandiose e-mail address lordwinston57@gmail.com and accompanied by a PDF attachment entitled HELMER.

The document, in French, was signed Alexander Arzamastsev but untitled – although the mention Fwd: helmer corrigé [helmer corrected] appeared in the e-mail subject bar. Starting Helmer’s name with a small h seemed a deliberate slur – eschewing the courtesy by which Tajan staff set such store. It set the tone for a 23-line diatribe. ‘It has been drawn to my attention’ began Arzamastsev portentously ‘that a certain John Helmer has published an article concerning a work by the Russian painter Chashnik, seeming to contest the provenance attested by the owner and cited in the catalogue as being the Costakis Collection.’

Helmer’s claim to have received information from the daughter of the late Monsieur Costakis struck Arzamastsev as ‘peu probable’ [improbable] as ‘the heiress to the collection would not hesitate to come forward if the sale of a work posed a problem as to its description.’

However, as we have seen, Costakis’ daughter Aliki had indeed come forward, with an email to Tajan on March 5 – of which Tajan seem to have left Arzamastsev wondrously unaware. (Perhaps Tajan staff find him as difficult to contact as journalists.) Arzamastsev nonetheless questioned Helmer’s ‘legitimacy’ as a journalist, summoned him to cite his ‘sources’ for asserting that he, Arzamastsev, was not known in Moscow, and accused him of ‘veritably harassing those involved in the Tajan sale.’ Helmer, continued Arzamastsev, ‘demands, insinuates, and even threatens…’

Any threatening was, in fact, being done by Arzamastsev. ‘If all the information I have received about Monsieur Helmer’s actions and declarations proves to be true,’ he thundered, ‘it is evident that their abusive and diffamatory nature will not remain without a response.’

I searched in vain, amidst all this aggressive rhetoric, for a rational defence of Arzamastsev’s expert input into the Tajan sale of March 8. Instead, he declared, the whole issue was a ‘faux débat’ [storm in a teacup] whipped up by Helmer solely to ‘further his reputation.’ Arzamastsev did not feel concerned: ‘As an art historian, I am not competent to guarantee a work’s provenance, nor undertake research unless I have been mandated to do so.’ After Cohn and Wattel, he now became the third person to declare that any issues pertaining to the sale of March 8 were nothing to do with him. Just where does the buck stop at Tajan?

The PDF was bizarrely dated 25 January 2016 (over six weeks before the auction and twelve weeks before Helmer’s article). This may have been machiavellian, but I suspect it was merely par for the unprofessional course.

I wrote to Anne Perret again to ascertain her opinion about the PDF – and specifically about Arzamastsev’s assertion that he was not competent to guarantee works’ provenance. Had Tajan, I wondered, deemed it unnecessary to carry out or commission research about the provenance of the Avant-Garde works offered for sale on March 8? Given the high number of fakes in the field, that struck me as surprising. I also asked her why Tajan had used the services of Mr Arzamastsev as expert, as I was no wiser as to his experience or credentials from reading the PDF. Madame Perret (below, left) did not reply.

I then wrote to Tajan’s press officer, Romain Monteaux-Sarmiento (above, centre) with whom I have been on amicable terms for many years. After referring to his colleague’s silence, I suggested that Helmer’s allegations about the March 8 sale seemed ‘sufficiently serious to warrant a detailed response’ from Tajan – preferably from the firm’s owner, Rodica Seward [above, right] Would she like to convey her version of the facts? Apparently not. Once again, I received no reply.

This was not the first time Arzamastsev had been involved with Tajan. According to one former employee, he approached the firm shortly after it was acquired by Romanian businesswoman Seward back in 2003, offering to sell a collection of Russian works. The offer was not taken up.

The most prestigious Avant-Garde work in Tajan’s March 8 sale was described as Liubov Popova: Construction Suprématiste. With an estimate of €300,000-500,000, it was expected to be the most expensive lot in the entire sale. The catalogue duly listed a five-line provenance, the final item reading Vente Christie’s du 8 avril 2007, lot 108.

There was no sale at Christie’s that day, anywhere in the world. Were Tajan deliberately trying to mislead potential buyers, or was this just a careless proofing error? There was, however, a Christie’s sale in New York ten days later, whose Lot 108 was indeed a Popova – and one that, in the catalogue (which I have in my possession), looks identical to the Popova offered by Tajan. Both are signed Л.Попова bottom right (something Tajan amazingly failed to mention), although their published dimensions are slightly different: 64.8 x 94.7cm according to Christie’s, 65 x 92cm for Tajan. Christie’s Popova, though, was not vaguely entitled Construction Suprématiste (below, left) . It was precisely entitled Birsk Landscape (right).

Source: Tajan catalogue, pages 50, 51 -- http://www.tajan.com/pdf/2016/Ventes/1628.pdf

Given that identifying the location of a work (Birsk is a town 800 miles east of Moscow, which Popova is known to have visited in 1916) invariably enhances its value, why did Tajan change the title (and dimensions)? Not to mislead potential buyers by making the work more difficult to track down on Artnet, surely?

Christie’s Popova was offered with a published estimate of $700-900,000 (£360,000- 460,000/ €540,000-690,000) but, like Tajan’s, did not sell.

The Great Birsk Popova mystery does not stop there. On 15 June 2007, just two months after the Christie’s sale in New York, a Popova Birsk Landscape surfaced at MacDougall’s in London (Lot 48). It sold for £514,000. Its dimensions were given as 65 x 91cm and at first glance – I again possess the catalogue – it looks pretty much the same as the Popova offered by Christie’s and Tajan. On second glance it does not.

It is not signed bottom right (MacDougall’s described it merely as ‘signed,’ though no signature can be seen in their catalogue reproduction); the contrast between its reds and oranges is cleaner and sharper; and, although the composition is identical, there are some small but undeniable differences in brushwork and detail.

MacDougall’s, London: http://www.macdougallauction.com/

Unlike Christie’s, MacDougall’s cited a 1994 restoration report by Lars Bystrom, Chief Restorer of Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art; and a letter from Mr Bystrom dated 29 March 2007, conforming the work offered was the same he had handled in 1994. But, as regards provenance, MacDougall’s and Christie’s were in total agreement. Both indicated that the work had been acquired by Dr Mahmoud Vaja of ‘Paris and Tehran’ in 1938; inherited by Nina Vaja of Stockholm in 1970; acquired by Annie Flygare of ‘Stockholm and Miami’ in 1976; then entered a Swedish private collection.

It may be that Lyubov Popova painted two virtually identical landscapes during her visit to Birsk, and each subsequently shared exactly the same owners. Or it may be that Popova painted just one Birsk landscape, which was crisply restored between the Christie’s and MacDougall’s sales in 2007, then returned to its original dingier state before being consigned to Tajan in 2016. Or it may be that at least one of the works is a fake.

Tajan’s gave the same provenance for their Popova as Christie’s and MacDougall’s – with one exception. Tajan failed to mention Nina Vaja as inheriting the work in 1940. Instead, they stated that it had been acquired ‘by descent’ by Annie Flygare in 1976. Artful omission or hallmark sloppiness?

Tajan are no strangers to Avant-Garde shenanigans. On 31 March 2011 they offered a ‘stunning collection of Russian paintings’ led by Natalia Goncharova’s Park In Winter (estimate €400,000-600,000) and The Scooter (estimate €800,000-1,200,000). Provenance in each case was given as the nebulous ‘Edward

Ellenberg Collection,’ with authenticity vouchsafed by Denise Bazetoux – who reproduced both works in her Natalia Gontcharova: Son OEuvre Entre Tradition et Modernité, also published in 2011. This was meant to be the first instalment of a three-volume Goncharova catalogue raisonné, but it attracted such a torrent of criticism that Bazetoux abandoned the project. Tretyakov curators declared that over half the works illustrated in her book were fakes.

Left: Natalia Goncharova. For more on the Bazetoux controversy, read this

‘After all the problems with the Russian avant-garde, I’ve taken my distance and prefer to devote my time to other painters’ Bazetoux told The Art Newspaper recently.

Problems? The Goncharova Scooter that Bazetoux authenticated for Tajan showed a vehicle that did not even exist in 1913/14 – the date she assigned to the painting.It scooted off unsold. So did Park In Winter.

Bazetoux is a member of InCoRM, a controversial group of art historians laying claim to expertise in the field of the Russian Avant-Garde. As we have seen, their President Patricia Railing cited ‘Moscow art historian’ Alexander Arzamastsev in an article she wrote in 2012. While researching this article, I e-mailed Mrs Railing – twice – asking InCoRM to vouch for Mr Arzamastsev’s credentials.

I received no reply.

[*] Simon Hewitt is International Editor of Russian Art + Culture, where his article was first published this week. The cartoon, pictures, and other illustrations in this republication were prepared by John Helmer. The Tajan catalogue page for the Chashnik drawing has also been reissued by the Tajan management. The attribution to the Costakis Collection is gone.

Leave a Reply