By John Helmer, Moscow

When Oleg Mukhamedshin, head of investment strategy for United Company Rusal, was in London recently, he complained the stock market isn’t giving Rusal’s share price a fair valuation, taking into account how much profit the non-aluminium line of business – that’s the dividend to be paid to Rusal by Norilsk Nickel — is likely to generate this year for Rusal’s loss-making bottom line. What Mukhamedshin didn’t mention is that the market suspects Oleg Deripaska, chief executive and manager of the controlling shareholders’ trust, of operating a scheme to protect asset value and income for an inner circle of Rusal shareholders, and let all other shareholders suffer the worst.

Initial evidence of the inner circle scheme was first uncovered in the records of RTI Limited (aka Rusal International Trading), a Jersey Island-registered entity which appears to be the next to highest control entity in Rusal’s corporate organization. Registered on October 27, 2006, one day after the parent company was incorporated in Jersey, RTI’s carefully worded articles of association contain a code which provides privileged treatment for one class of Rusal shares at the expense of the founding shareholders; the latter include Mikhail Prokhorov, Victor Vekselberg, Len Blavatnik, and Glencore; and the shareholders who “anchored” Rusal’s Hong Kong Stock market listing in January of 2010, including the Russian state banks.

Decoding the RTI documents and uncovering the inner circle scheme, are also an objective of a legal challenge to Deripaska’s compliance with the shareholding agreements which Vekselberg and Blavatnik have taken to court in London, where they are charging Deripaska with violations. Although that case is proceeding behind the closed doors of the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), there is suspicion on the part of Rusal’s free-floating shareholders that their paper is already discounted to the cashflow of the company. That suspicion is one reason Rusal’s share price falls more deeply in the commodity troughs than its aluminium-producing peers, Alcoa and Chalco, and fails to gain by as much value when they take off.

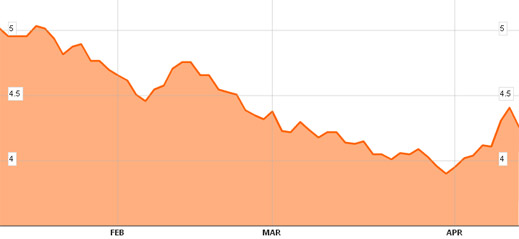

Last week, while the listed aluminium companies were enjoying an improvement in share pricing, Rusal shares were trading 15% below their peak for this year. Alcoa is 10% below its peak; and the Aluminium Company of China (Chalco), down by 27.5%. On a one-year rate of return calculation, Alcoa is down 8.7%; Chalco, down 16.6%; and Rusal down 25.4%.

3-MONTH SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY FOR RUSAL

Source: Bloomberg

Market sources in London ask whether Rusal shares remain weaker than its peers because the shares themselves are subordinated to a secret class of shareholders.

Research in the publicly accessible records of the Jersey company register reveals that when Rusal was first incorporated in October 2006, the articles of association anticipated that there might be more than one type or class of shareholding in the new company. This was just weeks after President Vladimir Putin had put a stop to Vekselberg’s independent effort to list his Siberian Ural Aluminium Company (SUAL) in London, and ordered a merger (takeover) between Rusal and SUAL. Glencore also participated in the formation of the new company, adding alumina refining assets in return for shares. At the time of the merger announcement, Deripaska was said to hold 66% of the new shares; Vekselberg and his partners, 22%; and Glencore, 12%.

The October 2006 Rusal formation documents indicate share capital of $10,000 divided into 10,000 shares of $1 apiece. Article 8 of the Rusal articles, dated October 26, 2006, refers to “special rights for the time being conferred on the holders of any class of shares”. These may “be issued with such preferred, deferred or other special rights…whether in regard to dividends, return of capital, voting or otherwise, as the Company may from time to time, by special resolution, determine.”

Article 18 allowed Rusal – meaning Deripaska, the control shareholder at the time – to create “different classes of shares”, with “special rights attached to any class”. These special securities, according to Art.18, “may be varied or abrogated”. Then follows several rules for this, including “consent in writing of the holders of the majority of the issued shares of that class”, or “a resolution passed at a separate meeting of the holders of shares of that class.” The Rusal rules allowed a quorum of such a decision-making meeting to be “two persons holding or representing at least one-third in nominal amount of the issued shares of that class.”

When it came to paying out Rusal cash from the profit stream, the 2006 articles allowed different classes of shares to benefit, including some with “preferential rights with regard to dividend.” There is nothing in the articles on dividends which obliges Rusal to publicly declare how much in dividends may be paid to the holders of the preferential rights. It also isn’t obvious from the articles that Deripaska was obligated to inform the SUAL and Glencore shareholders of such payouts.

The day after Rusal was formed in Jersey, RTI Limited was incorporated separately. This was directly connected to Rusal; the importance of that relationship has been reported here. Nine months later, in July of 2007, RTI registered a change of name to Rusal Trading International, and then another change of name back to RTI. This was at the time Mikhail Prokhorov was negotiating with Deripaska to sell the former’s stake in Norilsk Nickel to Rusal for a combination of Rusal shares and cash. That deal wasn’t finalized until April of 2008.

According to the Jersey record of RTI’s articles of association dated July 2007, the three forming principals of the company were Deripaska acting through the EN+ holding, SUAL and Glencore. Article 8 of the RTI charter is the same as Article 8 of the Rusal charter of October 2006. The 187 RTI articles are almost identical to the 181 Rusal articles, except for several provisions relating to shareholder meetings and advance notifications to shareholders.

RTI’s share capital, again according to its Jersey records, consisted of 20,000 shares, twice the number of the parent’s shares. Denominated in US dollars, just two RTI shares were paid up; they were registered as owned by Rusal. At the same time, the Jersey record shows that 1,600 redeemable shares were issued and paid up, way outnumbering those owned by Rusal. They are the quasi-control shareholders of RTI.

On February 10, 2010, RTI’s articles were changed. The timing was less than a month after Rusal shares were publicly listed for the first time, and share sales commenced on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. According to the prospectus for that listing, RTI had an exchangeable claim of $1 billion with Rusal. That suggested RTI’s redeeemable shareholders constituted a special class with preferential right to a billion-dollar share of Rusal. At Rusal’s present market capitalization, this represents about 12%.

The Jersey records reveal that on February 9, 2010, someone named Dzianis Sidarkevich signed on behalf of Rusal a special resolution of RTI. This altered the capital of RTI, increasing it, according to a new Article 6 of RTI’s memorandum of association. Now “the share capital of the Company is US$21,600 divided into 20000 ordinary shares of US$1.00 each and 1,600 redeemable shares of US$1.00 each.” Sidarkevich’s name does not turn up in a search of Rusal documents or of the internet.

The RTI articles were also changed to reflect the identification of the redeemable shareholders as a special class – the inner circle.

The old Art. 8 comprised 7 lines allowing for the possibility of a special class of shareholder. The new Art. 8 runs for 44 lines, and spells out exactly what rights the inner circle is holding. It also implies that between 2006 and 2010 Deripaska had been handing out special shares in RTI, with claims upon Rusal, to a variety of trust holders. The new Art. 8 attempts to limit who these are and what claims they can make. It begins with the statement that the new class of shareholders may hold their interest through a trust. But RTI won’t recognize claims by persons or trustees, or recognise “any equitable, contingent, future or partial interest in any share…except an absolute right to the entirety thereof in the registered holder”.

Art. 8A defines the “absolute right” this way. The “special rights attaching to the redeemable shares are as follows: (a)…at any time after 6 December 2013 the Company may redeem all or some of the redeemable shares. (b) …at any time after 6 December 2013 the Company shall at the request of a holder of redeemable shares redeem all or some of their relevant redeemable shares.”

The difference between the two sub-sections apparently gives Deripaska the discretion to pay out what is owed to a redeemable shareholder if he or she isn’t asking for a payout. But if the shareholder insists, files a redemption notice four weeks in advance after the operative date next December, and supplies the certificates for the redeemable shares to be cashed in, RTI and Rusal don’t have any choice. They “shall…redeem all or some of their relevant redeemable shares.”

There is no doubt about the meaning of the words, because Art 2 explains: “the word ‘may’ shall be construed as permissive and the word ‘shall’ shall be construed as imperative.”

For the next twelve months Rusal’s financial position improved significantly over the results for 2009. Sales revenues jumped 35% to $11 billion; operating profit multiplied by 140% to reach $3.5 billion. On the bottom line, Rusal reported for 2010 that its profit was $2.9 billion, three and a half times the profit for 2009.

But the good times weren’t to last. In 2011 sales revenues were up, but profit collapsed to just $237 million, less than a tenth of what it had been. In 2012 the financial results are even more parlous, with a bottom-line loss of $55 million.

Whether or not Deripaska was anticipating the downturn, he ordered a fresh change in the RTI articles. On January 20, 2011, the Jersey records reveal a new “special resolution” voted by “we, being the sole member of the Company [RTI] who would, at the date of this resolution, have been entitled to vote upon it if it had been proposed at a general meeting at which we were present”.

The change is reported this way: “That the articles of association be and are hereby altered by the deletion of the word ‘shall’ in the second line of article 8A(b) of the articles of association in substitution therefor by the words ‘may, at its sole discretion’.”

In other words, even the privileged RTI redeemable shareholders have now been told by Deripaska that he may be unable to pay out what he owes them on December 6 – the deadline the inner circle had been counting on for a payout of up to $1 billion. Their reaction has not surfaced, at least not directly; though the formula the Kremlin devised last December to channel Norilsk Nickel dividends to Rusal shareholders may be one sign of their insistence on a payout. Evidence of the discrimination in payout sums between the classes of Rusal shareholders is being readied for the London arbitration case.

Note: The revised RTI articles also warn the inner circle to settle family, marital or legal disputes they have among themselves before asking for the payout next December. According to the new Art 18, “in respect of a share held jointly by several persons, the Company shall not be bound to issue more than one certificate, and delivery of a certificate for a share to one of several joint holders shall be sufficient delivery to all such holders.” Art. 20(a) limits the number of persons holding a share jointly to four.

Leave a Reply