By Marios Evriviades*, Athens

Can a man gasping for breath as he is is forcibly suffocated with a plastic bag over his head, articulate his survival problem multisyllabically with a medicalized request to which he invited his killers to consent? “I’m suffocating… Take this bag off my head, I’m claustrophobic”.

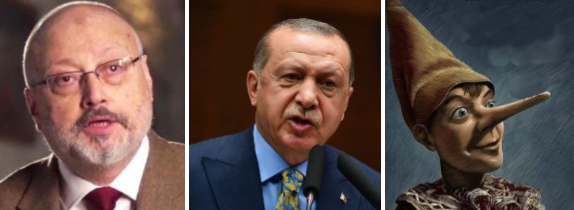

These are the alleged last words of Saudi politician and journalist Jamal Khashoggi (lead image, left), according to the latest leak from the Turkish intelligence agencies. If you are keeping count, this may be the 22nd in the series since Khashoggi’s disappearance in Istanbul on October 2. The last words come from the audio tape of a recording system installed, unsuspected and undetected in the Saudi consulate, by some of the finest electronic equipment the Turkish services have received from their western allies.

Before the new last words leaked into the press, there was no plastic bag. The previous Turkish version was that Khashoggi was attacked within minutes of entering the Saudi consulate at 13:14 on the fateful day; strangled by the bare hands of at least one, possibly two attackers, as he fought and screamed for his life. Those screams, according to an even earlier Turkish leak, were recorded on a device Khashoggi was wearing undetected on his wrist, primed to transmit to his Turkish fiancée standing outside the building.

Then there is the crucial matter of the corpus delicti. For without that, in a police or coroner’s court in a country other than Turkey, there is only the case of a missing person. That person’s body is missing, the world was originally told, because it had been cut into pieces with a bone-saw.

In disclosures to the press which have followed, the body pieces were taken in packages by car to the nearby house of the Saudi Consul-General. There they were either buried in the backyard, or thrown in a garden well, or carried off in another vehicle by a local Turkish subcontractor and disposed of in a nearby forest. Because Turkish investigators have found no trace of any of these things, we are now told that none of them happened. In addition, no explanation has been given by the Turkish services, which had earlier provided photographs of body parts, including a scalped head, allegedly Khashoggi’s, which have been circulating in Turkey and other countries.

The version which has followed in the more squeamish western press is that the body parts of Khashoggi were dissolved in acid at the home of the consul, and that is the reason we are now told the body could not be found. Strangely, no traces of acid were reported to have been found in the house or its well or waste system, after the Turks entered and searched it thoroughly days before the story of the acid appeared. The acid traces were reported to have been found in the house of the consul days later, once the earlier versions of Khashoggi’s “disappearance” had ceased to be plausible or possible.

The world has been asked by the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (lead image, centre) to believe all of this in sequence, and forget each story as the Turks released new ones. Also, the world was requested to share in the Turks’ moral outrage at the dastardly act. Turkish morality is the reason Erdogan’s subordinates threw a temper tantrum when the French Foreign Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian (right), accused Erdogan of “playing a political game” with the Khashoggi murder. The evidence Erdogan has been releasing makes this plain to everyone.

to believe all of this in sequence, and forget each story as the Turks released new ones. Also, the world was requested to share in the Turks’ moral outrage at the dastardly act. Turkish morality is the reason Erdogan’s subordinates threw a temper tantrum when the French Foreign Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian (right), accused Erdogan of “playing a political game” with the Khashoggi murder. The evidence Erdogan has been releasing makes this plain to everyone.

But not to the righteous Turks. Did not their president say to an international audience on October 23, and in an editorial he arranged with the Washington Post on November 2, that he will move “earth and heaven” to get to the bottom of the Khashoggi case; have the Saudi perpetrators punished no matter how high-ranking they are — Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s photograph is placed in illustration of Erdogan’s words, but he himself doesn’t dare name him. Erdogan has also promised to serve justice; give Khashoggi a muslim funeral; and ensure that nothing of this kind will ever again occur in a NATO member state. (These are not assurances Erdogan has offered the families of the fourteen Turkish journalists also still missing in Erdogan’s jurisdiction; seven of them confirmed dead, including the famous Hrant Dink. )

How dare anyone question Erdogan’s integrity? is the unanimous cry out of Turkey.

Let me tell you why. The Turks do not have to move “earth and heaven” now to get to the bottom of the Khashoggi murder. They could have done that within hours – repeat hours — of the reported disappearance of Khashoggi, by arresting the eighteen alleged Saudi murderers; by searching the premises of the Istanbul consulate and the residence of the Saudi consul; and by arresting him as a co-conspirator in the homicide. Within hours, the Turkish authorities reporting to Erdogan had all the prima facie evidence they needed to establish that a crime had been committed. But act they did not. Instead, they – that means Erdogan — allowed the alleged murderers to leave Istanbul on the evening after the crime was committed. They allowed the Saudi Consul, Mohammed al-Otaibi, to take his time – two weeks — before he departed on October 16.

On what the Turks did or did not do in their prosecution of the Khashoggi case, let Yasar Yakis (right) tell us. Yakis is a retired career diplomat, a former Turkish Foreign Minister and member of Erdogan’s Islamist party. In a subtle article, “What Turkey did and didn’t do about the Khashoggi murder”, published on October 24 in the English-language Turkish website Ahval, based in Washington, Yakis endorsed Turkey for what it “did”. He also went on to report what it “didn’t do”, and why. Yakis is quite revealing.

tell us. Yakis is a retired career diplomat, a former Turkish Foreign Minister and member of Erdogan’s Islamist party. In a subtle article, “What Turkey did and didn’t do about the Khashoggi murder”, published on October 24 in the English-language Turkish website Ahval, based in Washington, Yakis endorsed Turkey for what it “did”. He also went on to report what it “didn’t do”, and why. Yakis is quite revealing.

By citing the official time frame of Khashoggi’s disappearance, Yakis shows that the authorities had ample time to decide they were holding enough evidence that a serious crime had been committed on the premises of the Saudi Consulate and at the home of the Saudi consul in Istanbul; by a group of Saudi nationals carrying diplomatic passports who had flown into the country in two private jets and a commercial airline early on October 2. Since Turkish laws had been violated, the authorities knew they had the legal right, in line with the 1963 Geneva Convention on Consular Relations, to search the Saudi diplomatic premises, and arrest the suspects, including the Consul-General. Their diplomatic status, the Turkish authorities knew at the time and Yakis has repeated, guaranteed immunity from search and arrest only in the Saudi performance of diplomatic duties. Committing murder, as the evidence immediately suggested, was not one of them.

Yakis does argue that the relevant articles of the Geneva Convention limited the right of Turkish entry and search at the consulate and the consul’s home, putting off-limits the Saudi office archives and documents related to the diplomatic activities routinely carried out at the mission.

Additionally in his Ahval article Yakis discloses a crucial detail. Whether Yakis intended it or not, he reveals the deliberate and manipulative behaviour of the Turkish authorities. Fifteen of the alleged culprits departed in two private planes at 18.20 and 22.50 hours respectively, after going through regular customs clearance. Even if as Erdogan revealed in his October 23 statement the Turkish authorities did not learn the fate of Khashoggi until 17:50 on October 2 — a time that is patently false if the timeline leaked by Turkish intelligence is accepted as the truth – there was still plenty of time for the Turks to arrest the fifteen, plus another three of the conspirators who left on a commercial flight.

What is reported by Yakis is that “the plane carrying part of the Saudi team was stopped in the skies above Nallihan (a rural district in the Ankara Province) and ordered into a holding pattern, before being allowed on its way. If the plane had been forced to land, and its passengers put under questioning, a great deal of now unknown information would have been obtained”.

Yakis reveals that it wasn’t necessary for the Turks to move “earth and heaven” – all they had to do on the evening of October 2 was to prevent the alleged culprits from fleeing the scene of the crime, or stopping them at the airport, or in their airplanes before they left Turkish airspace. At that time, even if the Consul had been left untouched, the case would have been wrapped up in no time.

But Erdogan and his associates had other, more ambitious plans. It is those plans unfolding which have dictated each new leak. Had Erdogan decided to hold the eighteen fleeing Saudis, that would have meant rupturing relations with the Saudi kingdom, but this is something Erdogan and his officials repeat they do not want to do. However, such behaviour is exactly what the French foreign minister meant when he accused Erdogan, directly and personally, “that he has a political game to play in these circumstances.”

And what is this game? Foremost, the Turks are attempting to concoct an image of themselves and of their Great (Buyuk) Leader as defenders of justice and of international law and order, while extracting rewards for this pretence from all those, primarily the West and Israel, who have a stake in the stability of the present Saudi regime. If Khashoggi’s death was Saudi state murder, Erdogan’s game is Turkish state extortion. That makes two crimes.

This Saudi regime does not deserve sympathy. It must be held accountable, not only for the fate of Khashoggi, but for much more which the regime is responsible for in promoting war, terrorist violence and sectarian extremism from Syria to Yemen and further afield. Holding the Saudis accountable for Khashoggi’s murder is one thing. It’s not the only thing. Allowing Erdogan’s Turkey to prevail as source and judge of the truth of this case serves faking and falsehood, not justice.

[*] Marios Evriviades is a former Cyprus diplomat and presidential advisor. He is a professor of international relations at universities in Greece and Cyprus.

Leave a Reply