By John Helmer, Moscow

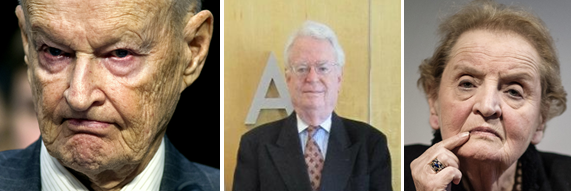

The widow of Cyrus Vance, the only US Secretary of State to resign in protest against his president’s actions in a hundred years, called Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor and Vance’s rival, “that awful man”. Not a single official of the State Department under Vance during the Carter Administration of 1977 to 1981, thought differently. Most of them had monosyllabic terms for Brzezinski. Since Brzezinski died last Friday, not a single member of his own White House staff has made a public statement in his honour, memory or defence. The mute ones include Madeleine Albright, who owed to Brzezinski her career promotion as an academic, then White House staffer, then Secretary of State herself.

Despite the disloyalty of those closest to him, and the detestation for Bzezinski of those further away, he was, and remained, Carter’s favourite. Between 1977 and 1981, Brzezinski’s time with Carter, according to the White House logs, amounted to more than 20% of the president’s working time. That’s 12 minutes of every hour — no other official came close. On Friday, shortly after Brzezinski’s death was announced by his family, Carter issued a statement extolling him as “a superb public servant…inquisitive, innovative, and a natural choice as my national security advisor …brilliant, dedicated, and loyal. I will miss him.”

What was this bond between them, and why does it matter now? One reason is that what they did together were the freshest American operations studied at KGB schools in Moscow by a recruit in training at the time named Vladimir Putin.

This was the National Security Advisor’s staff during the four years of Carter’s term, 1977-1981.

PRESIDENT CARTER’S RUSSIA-HATING TEAM

Pictured recently: above, Jimmy Carter. Below – 1st row: Zbigniew Brzezinski (died May 2017); David Aaron; Madeleine Albright. 2nd row: Paul Henze (died July 2011); Donald Gregg; Fritz Ermarth. 3rd row: Robert Gates; Samuel Hoskinson; William Odom (died May 2008).

A 451-page doctoral dissertation by Mary Sexton examining the relationship between Carter and Brzezinski identifies the evidence, including documents, witnesses, and independent reports which should have driven them apart. She fails to answer why that didn’t happen. She concludes Brzezinski flattered and fawned over Carter; relentlessly conspired to undermine Vance and other rivals for Carter’s attention; postured, manipulated, lied to the press, and faked to the president. Sexton concluded in 2009: “it is important to recognize that Jimmy Carter was ultimately responsible for the nature of his policymaking system and for the decisions made about who would frame and articulate U.S. foreign policies.”

She quoted Lloyd Butler, Carter’s appointee as the White House lawyer so no Brzezinski underling, as saying he was baffled by Carter’s refusal to address the troubles Brzezinski caused. “I will never understand it”, Butler said in 2002. He died in 2005.

Neither Vance in his memoirs (he died in 2002), nor his wife Grace, nor any of Vance’s deputies at State, nor Carter’s staff at the White House, provide an answer. In research by Betty Glad, published in November 2009, she reported “a few close aides met the emotional needs of the president”, but the aides didn’t tell Glad what they thought Carter’s emotional needs were. Glad acknowledged that in preparing her book she was “above all… indebted to Zbigniew Brzezinski who expeditiously answered my emails and was very open about his interactions with Carter.”

Glad concluded that Carter gave Brzezinski “his complete and absolute support… Brzezinski was one of the few people Carter never reprimanded…And Carter dismissed all criticisms of Brzezinski that might come his way.” Why?

“Carter needed and admired the strategic skills and the toughness in dealing with others that Brzezinski offered,” Glad summed up, with the latter’s help. The need to be tough was a recurrent theme in Brzezinski’s briefings and memoranda to Carter, she added. Brzezinski made Carter feel he was “doing big things.” Fighting the Russians (Soviets then) was, in the advice Brzezinski presented to Carter and repeated to Glad, was the biggest of the big things. “Brzezinski”, concluded Glad, “appealed to Carter’s desire to do new big things and act quickly”.

The bafflement reported by Carter subordinates and State Department officials under Vance is part truth; part cover-up by the officials; part deceit by Carter. The answer of what bound Carter and Brzezinski together Glad doesn’t uncover, nor even hint at. This is because it was a conspiracy of proxy wars, terrorism, assassinations, coups d’etat, and other black operations, still classified top secret, rationalized by Brzezinski to Carter and approved by the president, as part of a grand strategy to defeat the Kremlin. These were the acting-tough tactics which convinced Carter in secret, but which the president never admitted to in public. Not then, because the actions made Carter feel he was doing “new big things”. Not since, because all of them have failed, with bloodshed and monumental losses for those whom the president and his strategist targeted, and collateral damage for the rest of the world, not least the US.

“Sure, Brzezinski was a strategic thinker,” one of Sexton’s sources told her. “But he was frequently wrong! Vance’s strategies have withstood the test of time.” According to Sexton, her source was a “public official [with] in-depth familiarity with Vance’s and Brzezinski’s work. He agreed to be interviewed…on the condition he would not be quoted on this subject.”

Paul Henze came to Brzezinski’s staff after serving as the CIA’s station chief in Ethiopia in 1969 to 1972, and then in Turkey between 1974 and 1977. Henze had been one of the plotters of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in July 1974, which continues to this day.

The Somali invasion of Ethiopia which began in July 1977, and was known as the Ogaden war until the Somalis were defeated by the Russian and Cuban-backed Ethiopian military in March 1978, was one of the schemes Henze managed, and Brzezinski persuaded Carter to approve. By the time Henze’s war was defeated, he rationalized the war-fighting strategy’s continuing purpose in a memorandum since declassified and quoted by Sexton. “Much as we want the Soviets out”, Henze briefed Brzezinski and Carter, “we are not going to get them out soon…We should make their stay as costly as possible and the source of fundamental strain for them. We can do this in many ways, both overtly [and] covertly… The Soviets are the culprits in the Horn and we should never let them or the world forget it.”

Another of the Henze plots – the military putsch in Turkey in September 1980 – was Carter’s and Brzezinski’s scheme too.

Henze had started in the CIA as a specialist managing assassination gangs with pretensions to anti-communist ideology. He began with the Iron Guard of Romania, and was still running the Grey Wolves of Turkey when he moved on to the Brzezinski staff. After Carter’s downfall, Henze spent years trying to cover up the role the Grey Wolves had played in the attempted assassination of Pope John-Paul II in May 1981. Henze’s version of the plot was that the Kremlin and KGB had masterminded the scheme through the Bulgarian secret service. The KGB assessment was that Henze, Brzezinski and Carter had all been in on the plot, just as they had been in on the scheme to elect Cardinal Karol Wojtyła, Archbishop of Cracow, as the Pope in October 1978.

Brzezsinski’s euology at Henze’s funeral in Virginia in 2011 provided the cover story that he had engaged Henze in 1977 “to assume responsibility for oversight of the radios and to coordinate more generally our efforts to prevail in the Cold War without an actual war. Paul was in his element. He mobilized his enthusiasm, his commitment, and his boundless energy not only to protect RFE [Radio Free Europe], but to develop also a broader effort to nourish the hopes of those living in the Soviet bloc, including even the Soviet Union itself, that someday they, too, would be free.”

For their combined record of violent failure, Brzezinski had this to say: “Paul proved himself to be a ferocious bureaucratic infighter and eventually the winner – though at times he was even impatient with my efforts to pursue – on the President’s behalf — also some accommodation with the Soviet Union in the area of mutual arms control. But that was Paul, my fellow Cold warrior: enthusiastic, fearless, committed, principled, and relentless. A great American, an Eastern European by association, and one of the anonymous architects of the peaceful and victorious end to the Cold War.”

Henze was joined by other CIA men on Brzezinski’s staff including Donald Gregg, Fritz Ermarth, Robert Gates and Samuel Hoskinson. They were all plotters of the putsch which overthrew the President of Pakistan, Zulfiqar ali Bhutto, in July 1977. Bhutto was replaced by Army General Zia ul-Haq, and subsequently hanged. Zia was killed in August 1988, along with the US Ambassador to Pakistan, Arnold Raphel, and General Herbert Wassom, the head of US military aid mission to Pakistan.

Gregg was one of the plotters of the December 12, 1979, military putsch in South Korea.

For the declassified evidence, including Gregg’s claim “there are no smoking guns”, read this.

Hoskinson was engaged in Middle Eastern attack and overthrow plots, some he endorsed and assisted, and some he would have done if he judged they had a chance of success.

How many of the putsches which CIA operation histories log in as successful, and how many of the unsuccessful attempts – Ghana and El Salvador (1979), Bolivia, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, Suriname, Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Iran (1980) – were engagements in acting tough and doing new big things which Brzezinski got the president to approve are questions Carter is shy to answer.

For them, the war in Afghanistan, which they plotted with alacrity from the start of the Carter Administration, was the culminating case of what Brzezinski described in his address over Henze’s corpse as the “peaceful and victorious end to the Cold War.”

Left: the Red Army enters Afghanistan, December 1979. Right: the Red Army leaves Afghanistan, February 15, 1989.

These games of liquidating others in the cause of defeating the Kremlin has invigorated Carter, even today when Carter himself is on his last legs. Drawing the Russians on to the field of battle was his and Brzezinski’s aim; Afghanistan, after the Soviet military intervention began in December 1979, was their main chance. Their successors in the White House have the same chance against Russian forces on the battlefields of Syria and Ukraine. Though he has tried, Brzezinski is no longer in a position to advise them that if they don’t dare, they can’t win. Carter is still alive to demonstrate that if they dare, they are likely to lose.

It isn’t sure that’s what KGB trainee Putin scribbled down during his lectures at the Andropov Red Banner Institute in 1984. It’s certain he has noted it down now.

Leave a Reply