By John Helmer, Moscow

![]() @bears_with

@bears_with

Whoaaa Neddy! Another hack has gotten out of the stable of American exceptionalist historians of Russia.

Actually, this one, Eleonory Gilburd, is a Russian-born, US educated and employed hack of the Soviet Jewish emigration like Keith Gessen, Masha Gessen and Yury Slezkine. Russian exiles with axes to grind.

They have plenty to grind on – the Romanov tsars, the Orthodox Church, Bolsheviks, Communism, Soviet bureaucracy, Stalin’s Terror, the KGB, and the Russian intelligentsia – with the exception of themselves. There being almost no one in Russia for them to dare to sharpen an axe on when that would have been principled and brave, emigration to the US was the option. Gilburd’s book is a documentary, not so much of the Russia left behind, as of the generation created in the US by the 1974 Jackson-Vanik Amendment’s exchange of Soviet trade benefits for Jewish exit permits. They are the generation who want to return to a Russia, regime-changed and shaped in their image, and not to remain forever excluded, powerless, ignored as they are as Americans.

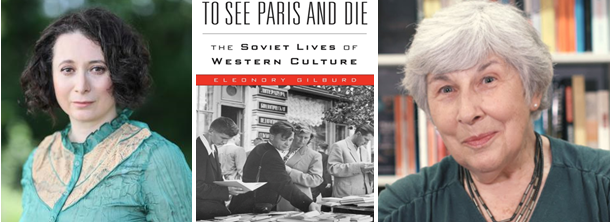

Gilburd’s (right) book, “To See Paris and Die” is a history of cultural contact between the Soviet Union and the west from 1958 to about 1970; that’s to say, from the start of de-Stalinization, through the Hungarian and Czech interventions of 1956 and 1968. Included is the Central Committee and Culture Ministry policymaking which gave rise to the Moscow Youth Festival of August 1957; the start of the Moscow International Film Festival in 1959, the Pushkin Museum’s exhibitions of French art in 1955-56, and the Picasso show of 1956. The focus is also on how the Soviets debated the theory of translation which governed the way the novels of Ernest Hemingway, Erich Maria Remarque and J.D. Salinger were translated into Russian for popular release, as well as major international films dubbed. Because there was nothing comparable in the Anglo-American translation world, Gilburd is unaware of parallel debates over foreign-language translation in Europe, especially among the Italians.

The culture is high to middle-brow. Pop music is left out; Edith Piaf’s and Yves Montand’s chansons included; ballet and classical music ignored. The bitter info-warfare between the CIA and KGB over writers like Boris Pasternak and Mikhail Sholokhov is also left out, Gilburd does concede that the American, British and French agencies were often the initiators, obliging the Soviets to play catch-up.

She thinks only in political and ideological terms, so she entirely misses the commercial terms of the culture trade, that’s “economic imperialism” in Russian translation. She acknowledges that “as the largest marketplace for film, the [Moscow] festival created a global cinematic network of coproductions and exchanges that contested Hollywood’s unilateral domination.” Gilburd the American academic has no idea of what the US film industry had done, before and after the war, to destroy competing European film industries, buying up cinema chains to monopolize distribution of Hollywood products; and what the French, Italians, and British were doing to save themselves.

Paris in the title is a misnomer. It’s a longing Gilburd attributes to Soviet citizens who, having survived the Revolution, civil war, Stalin’s purges, and German invasion, and who, regarding themselves as cosmopolitans rather than proletarians, wished to be somewhere else. Paris was only one of the locations – Rome, New York, Hollywood, London were others.

That might make a book on how Russians fell for the old cliché about where the grass is greener. But these days, when American exceptionalism meets Soviet exceptionalism, the outcome turns out to be a case of cultural cringe – Gilburd’s, backed by the University of California which gave her a PhD for the original manuscript and the Harvard printing house for multiplying the copies in circulation; and by an old teacher of Gilburd’s from the University of Chicago, Sheila Fitzpatrick.

The cringe, as Gilburd depicts it, is the sense of inferiority she thinks her sample of Soviets felt towards the products of western culture. Never mind that now, with more than a half-century of hindsight, a similar sample of westerners has come to comparably negative judgements of Hemingway, Remarque, Salinger, Fellini, Picasso even. Gilburd’s cringe, as it emerges from her book, is her sense of the superiority of her method of judgement, compared to what she repeatedly regards as “Soviet propagandistic clichés” (Marxism is not on the curriculum of the Chicago history department). But if the Soviet ideology of then turns out to have foreshadowed the western cultural market now, who should be cringing and in which direction, east or west?

In a recent review published in London, Fitzpatrick – an Australian with a cringe of her own towards her father’s pro-Soviet socialism — claims that Gilburd’s “chapters on the mechanics of cultural contact are tours de force.”

Left: Eleonory Gilburd. Her book (centre) was short-listed for the best book on Russia for 2019 by the London-based Pushkin House. Two others on the short list were Mark Galeotti, “The Vory” and Ben Macintyre, “The Spy and the Traitor”; all three failed to win. For their propaganda value in the current info-war against Russia, read this and this. Right: Sheila Fitzpatrick, a beneficiary of British Council operations in Moscow in the 1960s, reports in her Wikipedia bio as having Brian Fitzpatrick for a father but no mother. The difference between father and daughter is that the former wished that politically Australia would be more like the Soviet Union, while the latter wishes the opposite.

Force possibly, but as history and sociology they aren’t tours at all. For her claims about how Soviet citizens viewed western culture in the 1950s and 1960s – the period nicknamed the Thaw after Ilya Ehrenburg’s 1954 novel of that name (Оттепель) — Gilburd selected a sample of 1,100 letters sent to Soviet state organizations, authors and artists, plus 6,000 comments scribbled in visitor books at art galleries. She reports that most of them were by teachers, librarians, doctors, engineers and students; the majority was from big cities, 40% from Moscow and Leningrad; 9% she classed as “workers”. Gilburd also acknowledged – in a tail-end appendix – that she has not “treated these letters as statistically representative of a broader public opinion…it is a moot point as to whether they exemplified anyone’s experiences other than their own.”

The book preceding this disclaimer ignores it almost entirely.

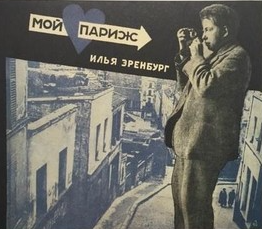

The title phrase is attributed to an earlier book of Ehrenburg’s, “My Paris” (right), published in Moscow in 1933. Oscar Wilde said it first and better: “When good Americans die, they go to Paris. Where do bad Americans go? They stay in America.” W.C. Fields put it best: “I’d like to see Paris before I die,” he said. “Philadelphia will do.” He also said about Philadelphia: “Last week I went [there] but it was closed.” And: “I once spent a year in Philadelphia. I think it was on a Sunday.”

published in Moscow in 1933. Oscar Wilde said it first and better: “When good Americans die, they go to Paris. Where do bad Americans go? They stay in America.” W.C. Fields put it best: “I’d like to see Paris before I die,” he said. “Philadelphia will do.” He also said about Philadelphia: “Last week I went [there] but it was closed.” And: “I once spent a year in Philadelphia. I think it was on a Sunday.”

In Gilburd’s history, as in the texts, films, and paintings she and her sources focus on, there are no ironies, no jokes. Better to say there are jokes, but she doesn’t approve of them when they were uttered; for example, when Nikita Khrushchev reacted to a Moscow show of abstract paintings (Soviet ones) in 1962, or the next year, when he fell asleep during a screening of Frederico Fellini’s film, “8½”.

Between academic jargon and Cold War cliché, Gilburd passes judgements like these. About Italian films: “Soviet readings of neorealist materiality were thoroughly Aesopian”; “in the Soviet Union Fellini and neorealism were related through the Chekhovian episodic and incoherent everyday”; “in its late decades, Soviet cinema was one long kiss in an adulterous affair. But when the kiss ended, there was no fade-out to guard the Soviets’ innocence.”

Gilburd doesn’t pretend to report on the genres of 20th century Russian painting, but she knows what she doesn’t like. “Socialist realism,” she concludes “pilfered from the nineteenth century.” Picasso, by contrast, was light years ahead: “Picasso exposed the ultimate boundaries of realism”. Also, “progeny without patrimony, they [young Soviet viewers] became Picasso’s heirs”.

Visitors to Picasso’s absinthe-drinking pilfer from Manet, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh, on show at the Hermitage in Leningrad in 1966. Source: https://www.bbc.com/

An American realist favoured by the Soviets, Rockwell Kent, speaking about his work in Moscow in 1967; source https://www.bbc.com/ Gilburd calls Kent by the old pejorative, “fellow traveler’. His decision to present paintings and papers to the Soviet Union after they had been rejected by the Farnsworth Museum in his home state of Maine was, Gilburd writes, a “grudge”. Gilburd hasn’t heard of the Yale University Press work of Matthew Bown on socialist realism, and she is plainly unaware of the rapidly rising value of it in the London, as well as Moscow art markets; read this.

When it came to books, the mass literacy of the Soviets, just thirty years old for Gilburd’s sample, had the result that “reading was a pivotal experience during the Thaw… Foreign books ‘about us’ interacted with—spoke to or against but never past – Soviet literature and journalism. The readings, therefore, were analogical (with Soviet problems) and compensatory (for Soviet prose): they endowed foreign texts with intimacy”. Yoo-hoo (Americanism, 1924)! – there is light at the end of this tenebrous tunnel.

Hemingway, for instance. Gilburd is still as keen on the old faker as she thinks Soviet readers were in her dedushka’s day. “He was an oracle. He was a measure of all things written, spoken, and done. He was a paragon of machismo and manhood, conscience and courage, nobility and knighthood, sincerity and heroism.” Gilburd dedicates her book to the memory of her grandfather, but doesn’t say whether the Revolution taught him to read. Her footnoted evidence for the claim about Papa Hemingway is a Russian academic work published in 2001.

Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye” as a case of extending adolescence into a philosophy of life hasn’t lasted so long among American adolescents. Gilburd turns it into an achievement of the Russian translator, Rita Rait-Kovaleva: “her translation created the image (original italics) of an existential book, and this philosophical reading had staying power.” Also: “Rait-Kovaleva’s translations have become canonical…[they] gradually helped to lift taboos on intimate love in literature, to reintroduce substandard speech in print, and therebty to break out of the ‘paralysis of language’ in which ‘words go dead under the weight of sanctified usage’.”

And Gilburd’s next to final word about books in Russian about abroad: “the book remained the centrepiece of travel experience and a prominent metaphor for the world. Journeys were mnemonic occasions for recalling books”. Finally, speaking in a radio promotion on the BBC’s Russian Service, Gilburd told listeners: “The main idea of the book is the paradigm of translation, not so much linguistic as translation as a mechanism of transfer to another semantic space, translation as naturalization and appropriation. I wanted to find a concept that would convey the active role of the host culture.”

At this Russian listeners turned off their wirelesses. But switched on through millions of digital devices, this is the stuff of which the daily Anglo-American war against Russia is made. “In the 1990s,” Gilburd adds in an epilogue, “the rest of the country [Russia] essentially emigrated to the West”. In war without guns, thinking can be weaponized like this. Still, when misfired, wishfulness can be a fatal wound.

Leave a Reply