By John Helmer, Moscow

The value difference and profit opportunity between a genuine piece of art and a fake are so large, there’s no deterring entrepreneurial forgers. Until now, the cleverest schemes have, ethnically speaking, been the specialty of Englishmen, Americans, and well-known art auction houses, museum curators and experts in connoisseurship. That last term is upper-class slang for hucksterism.

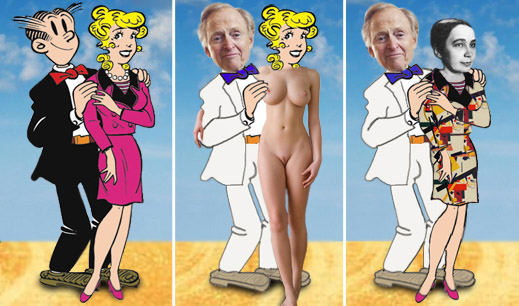

But when American Tom Wolfe (centre, right), exponent of what was called the New Journalism fifty years ago, exposes a Russian oligarch for a plot to make hundreds of millions of dollars in fakes through donating some to a Miami art museum, and selling others on the side, he has created a 700-page scapegoat for many things, including the loss of Wolfe’s talent.

Wolfe’s tale is set in Miami, which he’s at pains to explain from the get-go is mostly Hispanic and pretty venereal. Wolfe, now 71, is preoccupied with the mons veneris, which pops up often in the 107 pages before the oligarch appears for the first time. He’s called Sergei Korolyov. The descriptions of him are more the American fantasy of what they are missing in cash and potency than they are of any known Russian oligarch who’s ever dropped in on Miami, let alone lived there. There’s no resemblance to Dmitry Rybolovlev, for example, who bought the most expensive house in that southern American town. There’s the “square jaw, amazing blue eyes” – no resemblance to Dmitry Afanasiev, the Rusal lawyer, who also has digs in Miami. Square Russian jaws, remember, are the hallmark of the Russian villains in pulp British spy fiction.

Wolfe is famously pernickety for getting right the detail of object brand-names, locations, garments, and other human detritus. In the case of Korolyov, together with the other Russians in the story – Igor Drukovich, Mirima Komenensky, Boris Flebetnikov, art advisor Lushnikin, chess player Zhytin – Wolfe not only depicts them mangling their transition into the English language. He also transcribes their accents as a cross between Polish and Russian which noone speaks on either side of the border – unless they are wearing S&M gags, bear congenital harelips, or have suffered stammers since their military service.

President Vladimir Putin appears twice – on both occasions as the American epitome of cold, calculating violence. In one, a Jewish billionaire named Maurice Fleischmann, who is in treatment for genital herpes compounded by addiction to pornography, says: “Whattaya gonna do – get Putin to slip an isotope into my cappuccino”. A character less educated and less afflicted than Fleischmann claims Korolyov has “got the heart of one of those Russian Cossacks who used to go around cutting off the hands of little children caught stealing bread.”

Wolfe the investigative journalist does get to the heart of the Cold War, though, and why it isn’t over. This comes late in the book, with a disclosure that explains the reason white male supremacist Mitt Romney, and vacillating Barack Obama, have made such a to-do about Russia when their electors are concerned only about their jobs, taxes and pay. This is what Magdalena, the 24-year old Cuban-American target of almost every male organ in the book, is saying to herself as she wakes up before dawn in Korolyov’s “outsized [natch] bed in his great [natch] duplex in Sunny Isles”. She senses he’s feeling her up around the you-know-where, and thinks to herself: “she couldn’t believe a man his age could regenerate over and over, before they had finally gone to sleep…They couldn’t have been asleep more than a couple of hours – and obviously he was ready to go at it again.” Way to go, “Sergei Andreivich”!

There is a brief moment when American manhood reclaims the initiative by flooring Flebetnikov. “Here was a good old country boy who would happily beat a fat Russian senseless and feed him to the hogs.” Wolfe explains this is possible because Flebetnikov has lost all of his hedge fund on gas price futures, and at the moment of being beaten senseless lacks bank credit and bodyguards.

Wolfe makes a cameo appearance himself in the suit he made famous for a time in New York in the late 1960s. In the story Wolfe describes the maître d’ of a Miami restaurant called Chez Toi. “The maître d’ was instantly recognizable. He was the one dressed like a gentleman…He wore a cream-coloured tropical worsted suit and a necktie of darkest aubergine.” In reality, Wolfe was a shy man in that costume, and its ill-fit and poor cut gave the gentleman game away. He is still getting the geography of tailoring in London wrong, placing Jermyn Street off Savile Row.

For reality, real reality, Wolfe appears in the book for an instant to say, it’s up to the Russians to demonstrate. Correcting the phraseology of a television team at a party, Korolyov says: “That would be ‘real reality’? Then what would be ‘unreal reality’? …this is a reality show, I thought. And I speak lines by a writer? I think the English term for that is ‘a play’?”

In real Russian reality, there are oligarch-sized art collections. Alisher Usmanov, for example, bought the collection of Russian pieces collected by the late Mstislav Rostropovich after his death in 2007, diverting them from sale by Sotheby’s auction house to the Konstantin Palace in St. Petersburg. If Wolfe’s tale is to be believed, double-checking the authentication and valuation of the pieces in that collection might be a good idea, if only to allow the $40 million valuation of 2007 to keep piling capital gain on the palace’s books; and doing likewise for the items Mrs Rostropovich (Galina Vishnevskaya) has kept back at home.

There are other well-known connoisseurships of Russian art at the oligarch level. Sergei Frank is a notable collector of 19th century Russian painting of maritime scenes, especially of fareastern waters. Igor Shuvalov is a connoisseur of Russian antiques. Shalva Chigirinsky got his start in antique icons, and then assembled a fine collection of Shishkins. Vladimir Potanin made a well-known save of one of Malevich’s Black Squares (1915), and repatriated it. He paid just $1 million in 2002.

Much bigger numbers are ascribed to the three Russians listed by ArtNews of New York as top of the art pops. Roman Abramovich and his wife Daria Zhukova come first alphabetically; their speciality is reported to be “modern and contemporary art”. They are followed by Mr and Mrs Oleg Baibakov (“contemporary art”), and then Rybolovlev (19th and 20th century). If you spot works being sold out of their collections, Wolfe’s advice would be what art buyers already know — caveat emptor.

The valuations of collections like those, which are bound to be believed, are dwarfed by the size of Korolyov’s scheme, according to Wolfe’s tale. This involves the donation of faked Maleviches, Goncharovas, and Kandinskys to the Miami museum. The publicity generated by the jacked-up valuation of Korolyov’s $70 million philanthropy allows him to start selling privately an even bigger number of fakes, thereby netting him double, triple or quadruple the phoney valuation, depending on what he paid the forger, the experts, and everyone else who played a role in his scheme.

However, Drukovich, the artist employed by Korolyov, drunkenly reveals what he’s done to a local policeman and a reporter. After the news is reported by the latter in the Miami Herald, Korolyov rolls off the top of the Cuban girl; orders Drukovich murdered without trace; snatches back the forgeries waiting for sale in his studio; and just to be safe, flies off.

Before Drukovich tumbles off the mortal coil, he has this to say about the quality of early-20th century Russian painters. Regarding Malevich, “he try to be realistic. He haf no skill! Nozzing!” Between downing vodka – “Na zdrovia!..Now you honorary muzhiks!” – he explains that the Russian modernists are easy to copy because they had no talent to start with. Kandinsky, “when he start out, he try to paint a picture of a house…it look like a loaf of bread. So he give up and announce he start a new movement, he calls it Constructivism!” Goncharova (right image), “she is most unskilled of all! She cannot draw, and so she makes a big mess of straight little lines.”

It’s hard to be sure that extracting this confession is a triumph of investigative journalism on the part of the journalist, either the fictional Miami one or Wolfe in New York. “You lack sufficient objective evidence and have no eyewitness,” the storybook lawyer tells the Miami reporter, the editor, and the proprietor. “You can’t even indicate that Korolyov is to blame for any of it.” But then the corpse turns up. Then the newspaper lets fly with innuendoes against Korolyov, to which his lawyers Solipsky Gudder Kramer Mangelmann and Pizzonia respond with a libel warning. And then, ::::::yaaaaaagggh!::::::: the intrepid reporter gets hold of the evidence of the faked catalogue and the side sales. Wolfe has invented some new punctuation, and it’s all over for Korolyov.

The genuine Miami Art Museum opened its doors in 1996, and is rebuilding at a cost of $200 million. So far it appears to have bought or exhibited not a single Russian artist. Just four residents of Miami are on the ArtNews top-100 list – car dealer, doctor, lawyer and broker. As Wolfe makes clear, “any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.” The attribution to Russians, which is as central to the plot as the mons veneris is to the girls, looks to be something else.

Note: For the method, business and talent of art forgery, there is no better reader than the autobiography of Eric Hebborn, Confessions of a Master Forger, published in 1997. Hebborn was murdered in 1996. The quality of his work isn’t fictional.

Leave a Reply