by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

“I give you the floor”, Judge Hendrik Steenhuis announced to Prosecutor Thjs Berger, as he opened the June 10 session of the MH17 murder trial, the sixth day of the hearing at the Schiphol Judicial Complex in The Netherlands. The judge was referring to a court of law, not a stage show. “Ladies and gentlemen,” Berger began, certain it was a show he was opening. By the conclusion of his and Prosecutor Ward Ferdinandusse’s presentations, it was clear the show the Dutch are putting on in Amsterdam has been scripted entirely in Kiev.

The Hague District Court and the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security are broadcasting the MH17 trial sessions at this livestream link. They do not allow a permanent archive recording or a transcript. The Russian broadcasting system, through Ruptly, broadcasts each session of the trial in permanent form; watch the June 10 session here. The press are currently excluded from the courtroom. To date, the worldwide audience for the archive video recording is less than 4,000.

Steenhuis has adjourned for the opening of the defence presentation on June 22.

Historically, in British criminal courts the role of the judge was restricted over the years by parliament, along with that of the state prosecution; in parallel, the roles of the jury and the defence lawyer expanded. By this standard, Dutch procedure is archaic, a leftover of Roman Catholic canon law.

Dutch statutes and case law allow the judge much greater discretion than is lawful in the British or American courts. “The starting point of the Dutch system,” according to this recent analysis by Dutch law school professor and defence lawyer in Amsterdam, Stijn Franken, “is the idea that the establishment of truth – and thus the prevention of a miscarriage of justice – cannot be left to the prosecution department and to the defence. In Anglo-American systems, like in the UK and in the United States, these parties present their truth in a courtroom. In these countries, witnesses are for instance heard by the prosecutor and by the defence lawyer, not by the judge or jury. Cross-examination is a means to reveal the truth. In the Netherlands, however, truth finding is considered to be primarily and predominantly the task or duty of the presiding judge.”

Hendrik Steenhuis (left) was a state tax functionary for 28 years before he was given the post of judge in The Hague District Court in 2006. In 2016 the Justice Ministry entrusted him to convict the political opposition leader Gert Wilders, then challenging Prime Minister Mark Rutte in national elections. In Dutch jurisprudence the judge occupies a religious role. “One has to have faith in judges when giving them the task of finding the truth”, according to Professor Stijn Franken’s review. It is a relic of the Roman Church role of grand inquisitor.

“Our rules of evidence are, as a consequence, rather minimal. In everyday practice, it is fair to say that in the vast majority of criminal cases it is not rules of evidence, but the personal conviction of the judge that is decisive.” In current Dutch practice, “the concept of an active judge, responsible for finding the truth, makes it less important to attach much weight to enabling the defence to present its case. Consequently, a feature of the Dutch system is that the defence has no legal opportunity to call a witness of its own accord; the defence is deemed to ask the prosecution or the judge to call a witness for the defence.”

This week the state prosecutors have opened with a two-day summary of their case and the evidence they are claiming to prove that the four accused – three Russian soldiers and one Ukrainian – intended to murder the 298 people on board Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17, by firing a BUK missile in eastern Ukraine on July 17, 2014.

On June 9 Berger presented the prosecution’s proof of its case from radar and satellite data. The conclusion Berger reported to the court was that this evidence of the crime is either missing, or is subject to conflicting interpretation and reasonable doubt. On this evidence there can be no case to answer; read the details here, and the judge’s summary.

The next day in court, on June 10, Berger revealed that the remaining evidence against the four accused has been obtained from just one source — the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). It was the SBU which recorded the telephone conversations and recruited the eyewitnesses which Berger said the prosecution is now relying on to identify the names of the accused and their roles in the crime.

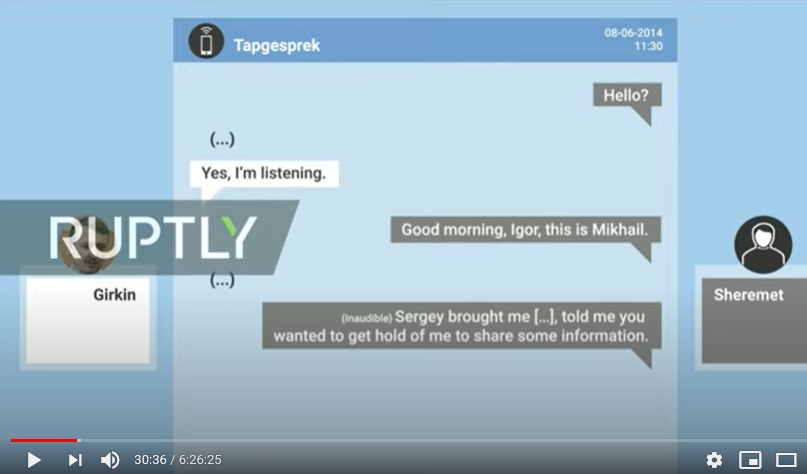

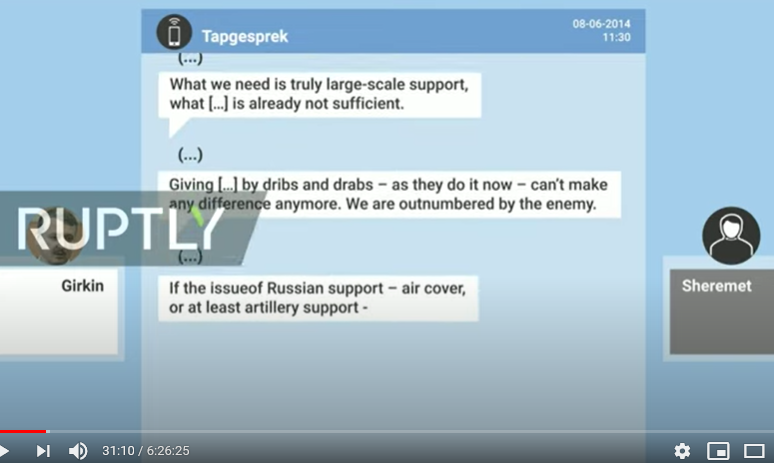

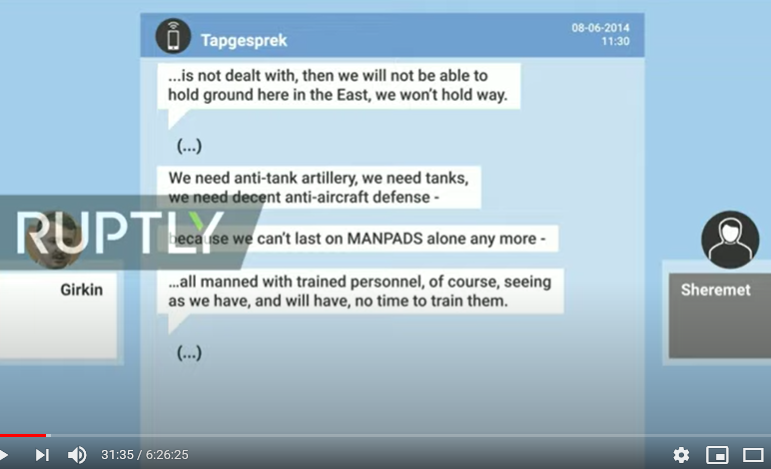

“The investigation of the role of these accused persons started with their identification,” Berger began (Min 23:14). “Early on in the investigation Ukraine disclosed intercepted telephone conversations in which people spoke about a BUK linked to or in relation to the downing of an aircraft on the 17th of July 2014. And since in eastern Ukraine on the 17th of July 2014 only one aircraft was downed, the relevance of those conversations quickly became clear” (Min 23:39). Berger went on to report the Ukrainian-source telephone tapes identified each of the four defendants, Igor Girkin (Strelkov), Sergei Dubinsky, Oleg Pulatov, and Leonid Kharchenko.

Berger explicitly pinpointed the SBU as the sole source of this evidence. “The investigation into the different roles of the different persons, the conversations that were intercepted in the Ukraine by the SBU [Min 27:47] became very important at very important points of time…we could quickly hear…how the accused talked about their BUK that had downed an aircraft” (Min 28:01).

This excerpt of an SBU tape of Girkin (Strelkov) talking about air defence for the Donbass from Ukrainian aerial bombing, mortar and artillery attacks was displayed and played in court as an example of Girkin’s culpability in the alleged crime:

Source: Min 30:36

Exhaustive independent analysis of these SBU interception recordings has been reported for months. These establish manipulation of the dates, texts, and voices in what is now presented as prosecution evidence in court; for details, start here.

Berger admitted there is a problem. “We consider it of the utmost importance to establish the authenticity of the conversations and we also have to check any accusations of manipulation by conducting a broad investigation into information from several sources. We now have a file that is very broad in which we can compare evidence and we can look at similarities and differences” (Min 29:24). This was a request for Judge Steenhuis to take the prosecution’s evidence on faith. It is also an acknowledgement by Berger that reasonable doubt exists independently of the prosecutors that telephone evidence from the SBU doesn’t mean what the Ukrainians or the Dutch intend it to mean.

The SBU is also the source of the only other evidence Berger claimed the prosecution is depending on. This is the testimony of the secret witnesses which Steenhuis and a panel of other District Court judges have allowed to be admitted in the trial. Starting at Min 34:39, Berger told the court that secret witness S07 had been a bodyguard of Kharchenko; S14 had worked under Dubinsky; S21, a subordinate of Kharchenko; and S29, “connected” to Pulatov. In addition, unnamed others reported by Berger to be “several former members of the armed forces of the DPR [Donetsk People’s Republic] were heard as witnesses” (Min 34:26).

The conditions in which these witnesses gave their evidence has not been disclosed, nor the way in which they had been recruited by the SBU. Berger gave the court no details of whether they had been prisoners of the Ukrainian Army, what rewards or what sanctions had been offered or threatened in exchange for their testimony against the names the SBU had identified in the telephone tapes.

Berger also did not tell the court the witnesses had been identified, recruited, rehearsed, and then presented to the Dutch by the SBU. The evidence of this has leaked from secret files of the prosecutors conferencing on their case preparations; read the file on SBU witness tampering here.

“Our ambition is to gather evidence,” Gerrit Thiry, one of the Dutch policemen working for the prosecution had said behind closed doors in January of 2018. The job of finding witnesses and getting them to talk, Thiry added, “depends on the help of the SBU to do the interviews in Ukraine.” The Dutch prosecutors at the same meeting were more explicit. Prosecutor Maartje Nieuwenhuis, chairing the meeting, conceded that without the SBU and its methods for persuading people to talk, “we simply cannot move on with our investigation without them.” Manon Ridderbeks, another Dutch prosecutor at the meeting said: “only the SBU is able to locate witnesses and bring them in.”

The leaked conference minutes reveal that in Australia, according to the Australian Federal Police representative at the table, the SBU’s role would be illegal and its witness evidence inadmissible in an Australian court.

Top: The courtroom of The Hague District Court at Schiphol as Prosecutor Ferdinandusse prepared to speak. -- Min 38:27 Below: compared to Prosecutor Berger, Ferdinandusse was nervous, constantly fingering his wedding ring for reassurance, reaching for a cup of water, and fumbling recitation of the script in front of him. That was until the last ten minutes of Ferdinandusse’s 50-minute presentation when he attacked the Russians and the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) for summary executions of civilians, torture of prisoners, looting, placing of landmines, and other war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Prosecutor Ward Ferdinandusse followed Berger. He started as a police detective in the MH17 case before he was promoted to the prosecution’s court lineup.

He began with a presentation of Dutch law and evidence to contest a claim of combatant immunity, if Pulatov presents it to the court when he has the opportunity; the defence lawyers have yet to say he will. This immunity is a highly controversial concept in the current law on warfare, with an “avalanche of legal scholarship, commentary, and analysis;” the US is opposed to extending the immunity to soldiers fighting in wars of national liberation.

Although the Dutch Government, the Justice Ministry and Joint Investigation Team (JIT) have already announced publicly that the four defendants were part of a line of command running directly up to the Defence Ministry and Kremlin in Moscow, Ferdinandusse argued that the conflict in eastern Ukraine was not an international one; that the four weren’t under Russian military command or control; and that they were individually culpable in the alleged crime because there was no military discipline in the area they controlled at the time.

That the military conflict in Ukraine began with the overthrow of the government in Kiev in February 2014, five months before the MH17 incident, was not mentioned. The involvement of the US and the NATO alliance in the events leading up to the regime change, the establishment of the new Kiev regime, and the direct US role in arming and directing the Ukrainian Army and Air Force against the national liberation forces in the east were not mentioned. Instead, Ferdinandusse told the court his “extensive investigation was done on the course of the armed conflict and the role of the Russian Federation in it” (Min 1:10:50).

That the US, NATO including The Netherlands, and Russia were engaged in proxy war in Ukraine — Ferdinandusse conceded without using the term — led to “conflicting [sic] information…on whether the accused and their group were factually under the control of the Russian Federation, but the strongest indications seemed [sic] to say that this was the case” (Min 1:10:20).

Ferdinandusse then launched a tirade. “In the case file we have information regarding the direct participation of the Russian Federation in the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, among others by artillery, shooting, executing those [sic], and offering their support and by utilizing and deploying militaries across the border” (Min 1:11:58). He said the Russian government’s role included providing military materiel, secure communications, and “recruitment and payment of fighters”.

With this Russian military backing, the DPR, he charged, “pursued a reign of terror where nobody was safe” (Min 1:21:46). DPR soldiers, the prosecutor added, were responsible for “extrajudicial executions and inhumane treatment of prisoners [Min 1:20:00]…executions, torture and inhumane treatment [Min 1:23:27]…torture of hundreds of civilians and Ukrainian military…crimes against humanity” (Min 1:24:12).

In Ferdinandusse’s recital to the court, the prosecution presented no direct evidence for the allegations; nor did Ferdinandusse allege there was evidence inculpating the four accused in any crime other than the one alleged. For his evidence against the DPR for collective crimes, Ferdinandusse identified anonymously “authoritative sources”, “some sources”, “reports of NGOs”, and “many neutral international sources”. He gave no details.

“The preliminary conclusion of the prosecution,” Ferdinandusse summed up, was the presumption of individual guilt in collective crimes. “The commanders of the DPR were violating the laws of war on a large scale” (Min 1:26:24). Girkin, Dubinsky, Pulatov and Kharchenko – Ferdinandusse never referred to the defendants by their full names, military ranks, or by the conventional honorific, mister – “were not members of the armed forces of a state. Their armed group was not fighting under the acknowledged responsibility of a state and did not respect the laws of war. Their group used on a large scale lawless violence that is bound by the laws of war” (Min 1:30:06).

Leave a Reply