by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

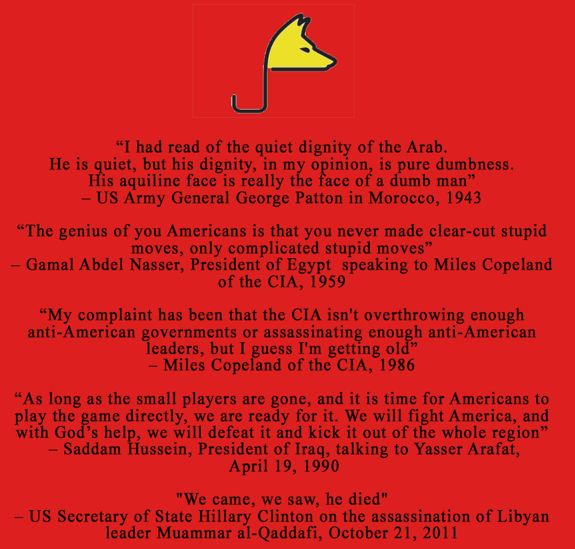

For eighty years since the US invaded Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia in 1943, American spies have targeted the Arabs for destruction, marking their leaders for assassination, stripping their people of the power to govern themselves. The US government agents planned the sabotage of Arab oilfields and theft of their water. They bribed the Arabs to fight each other. Convinced of American exceptionalism, lobbied by Israel, and bribed by US corporations, the OSS, CIA, Pentagon, State Department, and every president since Roosevelt have imposed their protectorate over the Middle East.

They have compelled the Arabs to pay Washington or die.

They have rewritten the law of genocide so that the murderers have gotten away with their crimes. They have covered their tracks with a blitzkrieg of propaganda and censorship. This is rassenkampf – race war as the Germans once pursued it.

Before the US Government went to war against the Russians in Europe, after the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, they practised in the Middle East on the Arabs. The methods and targeting are the same.

“My complaint has been the CIA isn’t overthrowing enough anti-American governments or assassinating enough anti-American leaders, but I guess I’m getting old”, said the CIA agent who plotted the murder of Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt as well as Arab leaders in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. As each of those plots turned into disaster, as US casualties mounted, and the price of oil skyrocketed, the American spies profited with personal promotions and wealth in retirement. “Nothing succeeds quite like failure,” concluded the Pentagon spy who paved the way to the fatal bombing of the US Marines in Beirut — the bloodiest episode in this history until the 9/11 attacks were followed by the defeats of the US wars in Iraq, Libya, Syria and Afghanistan.

This book reports from secret spy files discovered where they were buried in Washington. It is the first book to report in English from unpublished interviews with the Arab leaders themselves, including Saddam Hussein, Muammar Qaddafi, Saud al-Faisal, and George Habash.

The book manuscript has also survived the efforts of the CIA and the original New York publisher to bury it, just as the Arabs have been buried.

Read here of graves, worms and epitaphs, and sad stories of the death of kings. Read on to understand what happens next.

The book has been delayed.

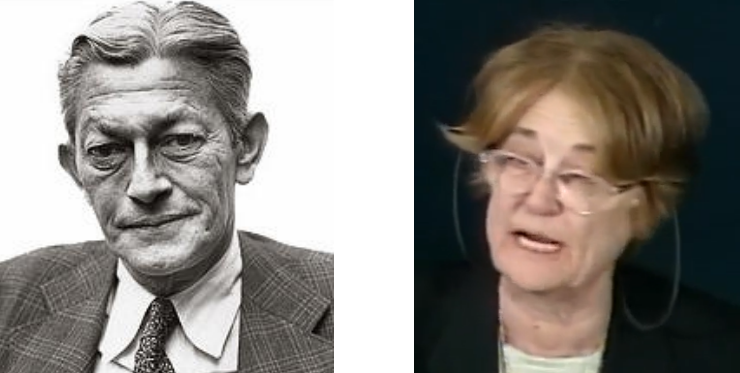

Early in 1987, with writing under way on the coordinated US and Israeli operations against the Palestinian organizations, Claudia Wright had telephoned James Jesus Angleton, the former head of the CIA’s counter-intelligence staff and of the Israel desk, to check a detail which had been revealed to her by one of the CIA’s Arab desk officers. By that time, they were all retired from the Agency’s payroll, but not from their old loyalties.

Angleton was dying at the time from lung cancer; he ended down the street at the Sibley hospital in Washington, imagining himself to be an ancient Apache warrior. Angleton learned from Claudia that Simon & Schuster was her publisher. After shortening the telephone conversation with her, he had a longer one with Alice Mayhew, the book’s commissioning editor in New York. She was persuaded not to publish the book – and not to communicate with us again.

Left: James Angleton in 1982; right, Alice Mayhew in 2003.

With Angleton, Mayhew shared a Jesuitical Catholicism and a prejudice for Israel.

Angleton hated many races, Russians foremost, then the Arabs. In the fate of this book Mayhew was just a cipher. The original manuscript was lost in a Washington attic between 1988 until last December, when it was found intact, the typescript pages thinning and translucent with the heat and humidity of more than thirty Washington summers.

The race hatred which Americans have shown, and continue to show towards the Arabs, and also towards the Russians, isn’t dead and buried like Angleton and Mayhew. This is the reason for publishing the book now. This book is not an epitaph for the dead, though. It’s a salutary lesson of the war-making and killing which race hatred produces, no matter who the race-haters say they are or what in their own histories they suffered themselves.

From the Prologue:

This book was written to describe how the US war against the Arabs began with the American conviction that the Arabs were an inferior race – inferior to Americans, that is, and even more inferior to Jews, because the Americans in the first chapters of this story were also antisemitic Jew haters.

That’s a mindset which the British comedian Spike Milligan revealed in his war memoirs, Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall, when he quipped that the Americans are the new Germans. He wasn’t joking.

In the chapters to follow, it can be seen just how closely the officials who have directed US policy towards the Arabs have been following the geopolitical calculations, military maps, oilfield blueprints, and political operations of the German general staff, the OKW of the 1940s. They failed because Hitler was too much of an antisemite to take the Arabs seriously as a political or military weapon, let alone ally; and because Hitler hated the Russians as much as the Jews and believed he could destroy them both. Without Hitler’s hatreds – krieg ohne hass (“war without hate”) the Wehrmacht generals in Berlin, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in Libya like to say they intended – the war would have been a close run thing.

The conviction of the Americans in this book was, still is, that they can destroy the Arabs and Russians both.

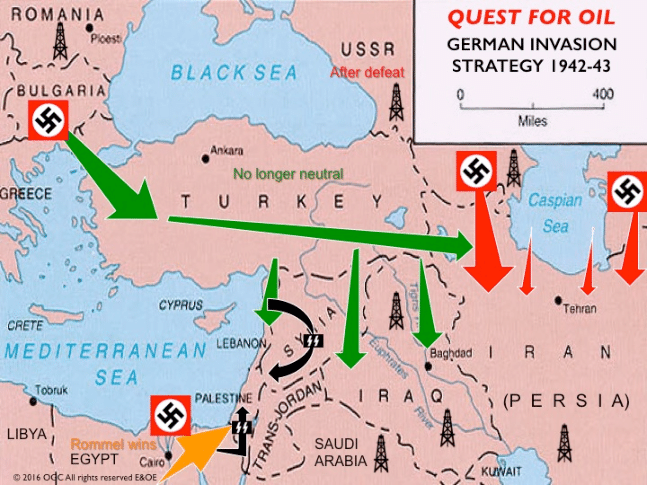

Revised after the failure of the Iraq revolt, Adolf Hitler’s War Directive No. 32 of June 11, 1942, envisaged the German invasion of the Middle East and Arabia from southern Russia (across Iran and Iraq), the Balkans (via Turkey), and Egypt (via Sinai). But the plan depended on the success of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the end of Turkey’s neutrality, and Field Marshal Rommel’s victory across North Africa to Cairo.

From Chapter 3, Following the Jackal’s Trail

William Eddy’s career as the first US spy in the Arab world had been one betrayal after another. In Morocco there had been the tribesmen of the Rif, the refugees from the Spanish civil war, the communists, and the Moroccan nationalists in Fez; in Tunisia he had had helped topple the Bey, allowing the French to replace him with their puppet; in Saudi Arabia he had schemed against Abdulaziz and Saud; in Beirut he was an informer against the moslem nationalists in rebellion against the corrupt administration of the pro-western Maronite Christians . He thought Nasser and Abd al-Karim Qasim, the anti-western rulers of Egypt and Iraq, deserved assassination. His last years were taken up with a multitude of CIA plots to do just that – and in Syria also where, as he had once said, there were no longer any “pro-American, moderate, honest dictators.”

Eddy believed there had been only one betrayal – that of the Arabs by American Zionists and supporters of Israel. He never understood how his actions had worked to their advantage nor blamed himself for their successes. He was the godfather of the new generation of US spies in Arab world – literally, the uncle of three – whose ear for Arabic he wasn’t able to pass on, but whose stock-in-trade was the same: intimidation, bribery and false promises.

THE FIRST US SPY IN THE ARAB WORLD

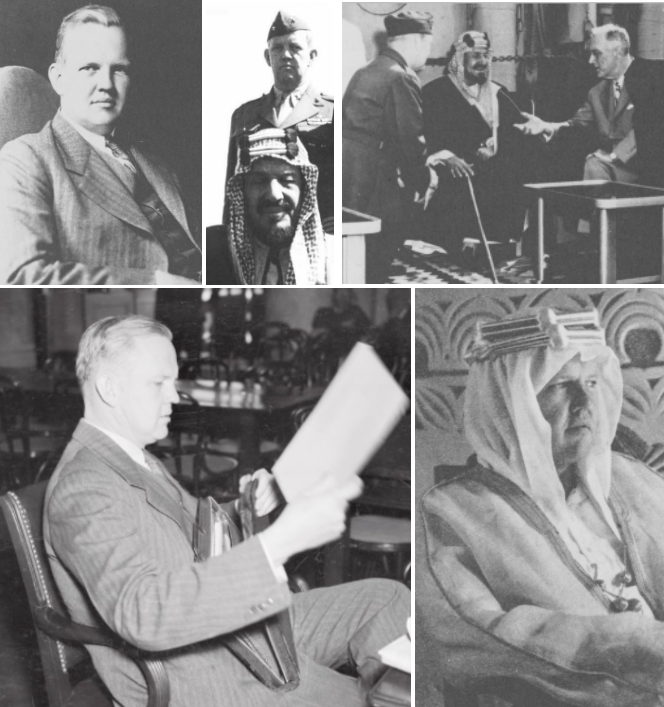

Top: William Eddy as president of Hobart and William Smith Colleges, upstate New York, in 1936. Eddy in Army lieutenant-colonel’s uniform standing behind Saudi King Abdulaziz on board the USS Quincy for meeting with President Roosevelt, in the Suez Canal, February 14, 1945, where Eddy acted as Arabic interpreter for the President. Same interpreting episode.

Bottom: Eddy pretending to be an Arab in costume presented to him in Riyadh in 1945.

From Chapter 4, Dreamers of the Day

Allen Dulles’s decision to turn to the Mossad was a fateful one. It directly links the 1958 death of Eugene Burns in Baghdad to the assassination, a quarter of a century later, of Robert Ames, the chief of the Middle East analysis branch of the CIA, and six other Agency officials, who died when the US Embassy in Beirut was bombed in April 1983. The Israel connexion was what had brought Ames to Beirut, along with the return of the US marines to the city; that connexion provoked the campaign of Arab terror against Americans and killed more CIA agents in a single blow than had died in the Middle East since the Agency had been established.

The CIA’ s relationship with the Mossad was administered from the beginning by the man Dulles had appointed to direct US counter-intelligence against the Soviet KGB, and run the Israel Desk at the same time. This was Angleton; Dulles ordered the Middle East operations division to do nothing without coordinating with him.

Angleton and Mossad were the real beneficiaries of BLUE BAT and of all the CIA operations that had gone off half-cocked before it. For fifteen more years they would work together to make Israel’s plans for the Arab world an indistinguishable part of American strategy against the Russians. They would ensure there could be no accommodation with Nasser; no lack of US military support when Israel went to war again with the Arabs; no hesitation in treating Arab nationalists as Soviet stooges.

The Syrian who would ultimately challenge the US-Israel connexion more violently than Nasser had ever done, was a rookie pilot in the Syrian Air Force during the events of 1957 and 1958. He observed them at a distance, while studying at a Soviet military school in Moscow. He was Hafez al-Assad, and he would prove much cleverer than Angleton gave him credit for. That miscalculation would cost the US dearly.

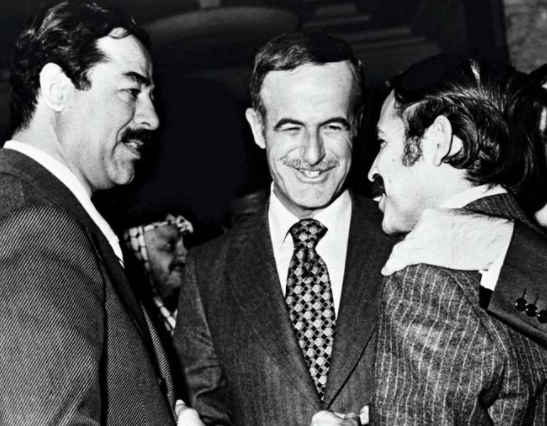

Syrian President Hafez al-Assad (centre), father of the current Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, at an Arab League summit meeting in Baghdad in November 1978 with Saddam Hussein of Iraq (left) and Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria (right).

From Chapter 7, The Crazy Boy

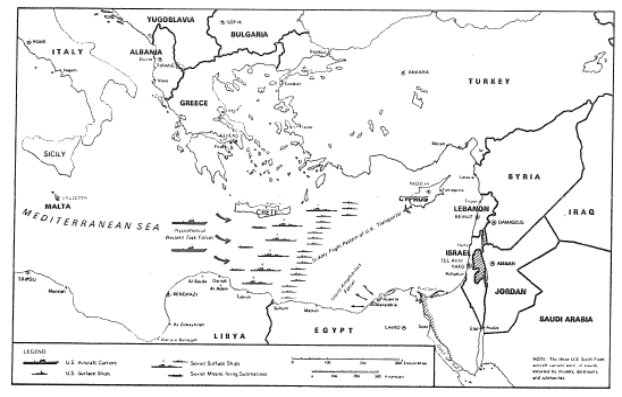

SOVIET NAVAL FLEET DEPLOYMENT BETWEEN CRETE AND LIBYA

ON THE DAY OF MUAMMAR QADDAFI’S COUP, SEPTEMBER 1, 1969

The Soviet naval exercise was planned to demonstrate Moscow’s willingness to come to Egypt’s rescue in the event of Israeli attacks. The Soviet warships all faced in the direction they anticipated the US Sixth Fleet might move in support of Israel. At the same time, this line of Soviet ships cut directly across the flight path which British aircraft would be obliged to take between their bases in Cyprus and airfields in Libya after the Libyan King Idris asked for British intervention to counterattack Qaddafi.

To [US Secretary of State Alexander] Haig [in January 1981] it looked as if he could strike at Qaddafi with impunity – the Russians would not intervene. He reported this conclusion to the NSC. Another NSC member agreed. “We concluded pretty early,” he says, “that we wouldn’t be able to do business with [Qaddafi]. He is just a bad actor. It was irrelevant to worry about driving him closer to Moscow.” The President agreed to authorize detailed planning for a series of steps leading to Qaddafi’s overthrow. Haig told Robert McFarlane, his newly appointed counselor at the State Department, to take charge of a special inter-agency group to work out the details. McFarlane, a former Marine Corps colonel who had helped draft papers on Morocco and Libya for the State Department transition team, was keen on making Qaddafi an early illustration of the Administration’s toughness. From McFarlane’s staff, the word was passed to the Israeli Government – this time the Administration was determined to get Qaddafi.

But Haig had misread the Russians and in his first soundings clumsily tipped his hand. Within days of the conversation with [Soviet Ambassador Anatoly] Dobrynin, a coded summary arrived at the Soviet Embassy in Tripoli. The ambassador was instructed to pass on the message in a personal meeting with Qaddafi. Further word arrived from Moscow about the American soundings. Court gossip from Morocco, suggesting that Haig or McFarlane might have tipped off King Hassan, also reached Tripoli, pointing to the same conclusion. The Soviet ambassador suggested to Qaddafi that now was the time to make an official visit to Moscow. If the Americans were to be deterred, the Soviet official suggested, then perhaps the Libyan leader would consider signing the much discussed, but never concluded Soviet-Libyan treaty of friendship.

Qaddafi wasn’t sure whether Moscow was bluffing, exaggerating the American threat in order to panic him into the treaty. On February 15 he began cautiously to let the cat out of the bag. He told a West German interviewer that he supported Syria’s decision to sign a treaty with Moscow “in its present situation facing the enemy.” If the talks then under way with the Syrians to arrange a unity agreement with Syria succeeded, Qaddafi intimated, then Libya would be happy to accede to the Syrian-Soviet pact. “We too” he warned, “might find it necessary to conclude such a treaty.”

To Russian officials specializing in the Middle East and North Africa, Qaddafi had always been difficult to deal with, especially on arms. He was “explicit in personal talks, but he had a handicap when he started years ago of no patience. He cannot be a party to an easy compromise. That explains many problems in Soviet-Libyan relations. In a sense, his approach is all or nothing – say yes or I go. Qaddafi is rational. We know what he means. He has not been inclined to think objectively – however, he is courageous. He appears irrational, but idealists often appear like this.”

Idealism is no compliment in the Soviet political vocabulary, and the Soviet foreign ministry official speaking is fluent in Arabic, with many years of experience throughout the Middle East. His assessment of Qaddafi is indicative that on the Soviet side there is considerable wariness and mistrust.

The Soviet assessment of Qaddafi has itself undergone considerable change. Early in 1974 President Leonid Brezhnev had told the Egyptian foreign minister that he thought “that young man is crazy. He is always attacking the Soviet Union vehemently, without any justification whatsoever. Until now I have refused to meet him, although Nasser told me that he was a nice boy. He is an unbalanced fanatic!” As an afterthought, Brezhnev added that he considered [Qaddafi’s deputy Abdessalam] Jalloud “is more balanced.”

Later, after Jalloud offended Brezhnev by hectoring him during a meeting in Moscow, the Soviet view changed. Jalloud, the Russians now say, “cares for nothing. He is an actor, a nonentity.”

Qaddafi on his first visit to Moscow, April 27, 1981, with President Leonid Brezhnev and Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to his left; behind and to Qaddafi’s right, Libyan Foreign Minister Abdulati al-Ubaidi.

There is an obvious contradiction in the American claim that Qaddafi was a surrogate or agent of the Kremlin. If the Reagan Administration seriously believed it, it would not have contemplated plotting to topple Qaddafi without running the risk, sooner or later, of falling into direct military confrontation with the Soviet Union. Would the Russians let slip their military investment – in the past decade they have supplied at least $10 billion worth of arms to the Libyans who have paid in cash or in oil – with the same meek acquiescence demonstrated when Sadat expelled them from Egypt in 1976?

Difficult though it may be, the Reagan Administration concluded that the Russians would allow themselves to be undermined in Libya by an American plot to overthrow Qaddafi. US officials chose to tackle Qaddafi precisely because they did not expect the Soviets to intervene – because they thought the Soviets shared their view of the “crazy boy”, as Sadat had called him. Once Moscow had held that view, but time and the relentless US pressure to annihilate Arab nationalists like Qaddafi changed it.

In its Libyan miscalculation Washington was fortunate not to have lost any American lives. In Lebanon, against a more experienced Arab adversary, the luck ran out.

Leave a Reply