By John Helmer, Moscow

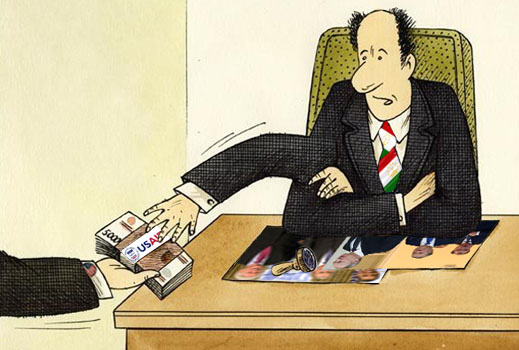

Paying bribes to your enemies to switch sides and become your friends is as old as monkeys and men (and women). As gang and warfighting strategies have evolved, corruption with money was always to be preferred to force with arms because corruption is much cheaper, and the results more predictable, at least in the short run.

A new book on corruption in the former Soviet states of Central Asia provides a handy reckoner of the colossal sums of money which have been exchanged to sustain the ruling regimes, or to change them. Alexander Cooley’s and John Heathershaw’s “Dictators Without Borders, Power and Money in Central Asia”, just published by Yale University Press, is also an encyclopedia of palaces owned in the UK, France and the US by the rulers of the Central Asian states and their hangers-on; the names and fates of the principal opposition leaders in exile from those states; a dossier of renditions, arrests, and assassinations carried out by the Uzbek and Tajik security services abroad; and case studies of the billion-dollar larcenies of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz bankers, Mukhtar Ablyazov and Maxim Bakiyev; of the Uzbek heiress Gulnara Karimova; and of the Tajikistan Aluminium Company (Talco) controlled by the Tajik President Emomali Rahmon.

The new book is also a valuable balancer on the side of independent research and antidote for the propaganda to be found from US and UK Government-funded think-tanks such as the Carnegie Endowment, Brookings Institution, Freedom House, and Chatham House.

When painstaking exposition of detail is required for the reader to understand the borderlands between force, fraud and subversion in Central Asia, and informed sources don’t readily talk – or tell the truth — there is only so much violence and corruption that can be fitted into three hundred pages.

Cooley (below, left) and Heathershaw (right) opted to start with the domestic politics of the Central Asian states, and how their abuses of power have spilled into the rest of the world. Heathershaw has lived and worked in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan; that adds direct source value which is scarce in the analysis of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Cooley and Heathershaw encourage the calculation but give less attention themselves to measuring how much more has been spent in these states by the US than by Russia; and how much less political success has been achieved with its money by Washington, compared to Moscow. And that has turned into bad news. For when corruption fails in politics, military measures inevitably follow. That’s why there is peace, relatively speaking these days, in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. The failure of corruption explains why there was the Georgian war of 2008; and why there has been the Ukraine war since 2014. (Those two conflicts are no more than footnotes in the new book.)

The failure of corruption as state strategy on the part of the Clinton, Bush, and Obama Administrations also explains why selective prosecution of money-laundering is also a US tactic against Russia, and why that too has been failing in its regime-changing purposes. For a detailed example, read the story of US protection of Ukrainian politician Yulia Tymoshenko’s corruption and for the ongoing US prosecution of Ukrainian oligarch Dmitri Firtash.

Russia’s relative success at applying corruption as a foreign policy tool is plain. Less than twenty years after the break-up of the Soviet Union and the independence of its member states, and less than a decade after Russia was virtually bankrupt, in default on its treasury bonds, several Russian oligarchs had managed to establish themselves on the controlling heights of the economies of what in Russia is called the Near-Abroad (ближнее зарубежье). That is a Russian political term, not just a geographical one. It’s much bigger than the term Ukraine, which a thousand years ago meant the land on the border, as it still does.

The Near-Abroad also includes the former Soviet states of the Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia), as well as Belarus. In Russian “Central Asia” is a fraction of the bigger term; it refers to Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, but not Kazakhstan. As a term used outside Russia, Central Asia is restricted geographically, including Kazakhstan but excluding the Caucasus. “Turkestan” is a 19th century term which included the collapsing Ottoman Empire, now Turkey. The “Eurasian Balkans” has been another term used by Americans for strategic comprehensiveness to include all of what Russia means by the Near-Abroad except for Belarus. Zbigniew Bzezinski, the one-time national security advisor in the Carter Administration and wannabe Russia warfighter ever since, also included Afghanistan in his map of Russia’s Near-Abroad, as he devised methods for shrinking the map on the Russian side.

Russia’s Near-Abroad is equivalent to the zone of Washington’s influence first spelled out by President James Monroe in 1823. Territorially, the latter was much, much bigger – hemispheric, in fact. At its inception, though, the Monroe Doctrine was agreed with Russia and Great Britain, which already had colonies over the northern border of the US, and intended to keep them. Monroe’s targets were south of the American border.

When the USSR collapsed in 1991, the Kremlin’s administrative resources to preserve the Near-Abroad evaporated. Preoccupied with saving himself, then enriching his retainers, President Boris Yeltsin was obliged to accept the dictates of a group of boyars, as the medieval tsar’s cronies, financiers and potential rivals were known.

President Yeltsin with his three boyars (left to right): Vladimir Gusinsky, Boris Berezovsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Once President Vladimir Putin felt secure enough domestically, the boyars were turned into an oligarch system. The boyars were unhorsed and disarmed, then institutionalized around the Kremlin palace table for an annual Christmastide celebration.

Putin turned them to account for Russian security strategy abroad. They tried but failed in the Americas and in Europe. They succeeded in the Near-Abroad.

By 2010, the Russian oligarchs owned the major metal and mining companies of Tajikistan and Georgia; they managed the purse-strings of the ruling Karimov family in Uzbekistan through mobile telecommunications and other concessions. They did this despite intense competition from Russia’s much richer western adversaries – the US, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU). But the Russians couldn’t manage this by themselves. Without record high prices for oil, minerals and gold, the bribes of the Russian oligarchs would have been a pittance beside the rewards on offer from Washington, London and Brussels. As Cooley and Heathershaw document, the Russians also needed help from the courts, banks, financial regulators, and PR companies in those capitals. They grew rich, too.

One of the Kazakh palaces which Cooley and Heathershaw missed: No. 15, St. James’s Square, London is the residence of Alexander Mashkevich. For more details, read this.

Instead of the military, administrative and financial controls of the Soviet-era system, the Kremlin has used the oligarchs to restore a significant measure of its previous influence. Not as directly nor as obviously potent as the Communist Party, KGB security, Gosbank rouble, and the Red Army commands had been before 1991. Notwithstanding, the oligarchs have been effective in restoring personal influence with the Central Asian governing elites, obtaining thereby unique means to anticipate and neutralize such threats to Russian state interests as may have been in contemplation by the Americans. The Russians were able to do this by paying cash — at a minuscule fraction of the old Soviet price.

In the Anglo-American power centres, intent on establishing their own sway in the Central Asian states, the Russian payments have been, still are, regularly exposed and denounced as corruption and criminal fraud. From the Kremlin’s point of view, it was, still is, pure expedience, as Lenin had once explained: “A scoundrel may be of use to us just because he is a scoundrel.”

The US strategy is the same. But the succession of one scoundrel after another in the Near-Abroad is currently not working to Washington’s advantage, not even in the most expensively corrupt operation in Ukraine.

Reliant for sources on US Government operations in Central Asia on the relatively anodyne cables from State Department embassies to headquarters, published by Wikileaks, Cooley and Heathershaw reprint this secret one from US Ambassador Tatiana Gfoeller in Kyrgyztsan in September 2009. Gfoeller (below left) was reporting on Maxim Bakiyev (right), son of then Kyrgyz President, Kurmanbek Bakiyev: “smart, corrupt, and a good ally to have.”

In Putin’s scheme of influence, Russian oligarchs have been granted licences to build lucrative cross-border businesses by doing what they had done inside Russia during the Yeltsin period. By individual bribery, by corrupting the administrative mechanisms of state asset privatization, and by schemes of offshore trading and capital transfer, these Russians acquired control of cashflows which were strategic for the countries concerned. These cashflows were transferred abroad, and shared with the ruling elites at home. The latter became thereby billionaire proprietors at their countries’ expense; and retainers in the Russian influence system.

Cooley and Heathershaw describe what the system looks like today. They don’t investigate how it is shaped by the ongoing competition between the US and Russian governments, even less with the Chinese government, and not at all with the Turks, the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Compared to the methods, amounts of money involved, and the outcome  in the case pursued by federal US prosecutors against James Giffen (right) for bribing high Kazakh officials, the Russian scheme of influence has been far more valuable to the Central Asian elites; more durable over time; more successful for Russian state interests. Even the US Government, after seven years of prosecuting Giffen, was obliged to concede Giffen’s defense to the corruption charges – that he had been engaged by the US secret services to be “their eye and ears there” .

in the case pursued by federal US prosecutors against James Giffen (right) for bribing high Kazakh officials, the Russian scheme of influence has been far more valuable to the Central Asian elites; more durable over time; more successful for Russian state interests. Even the US Government, after seven years of prosecuting Giffen, was obliged to concede Giffen’s defense to the corruption charges – that he had been engaged by the US secret services to be “their eye and ears there” .

William Pauley, the federal judge in the case, even endorsed the strategic value of what Giffen had done: “Suffice it to say, Mr. Giffen was a significant source of information to the U.S. government and a conduit of secret information from the Soviet Union during the Cold War. He undertook that effort as a volunteer and was one of the only Americans with sustained and reliable access to the highest levels of Soviet officialdom…These relationships, built up over a lifetime, were lost the day of his arrest. This ordeal must end. How does Mr. Giffen reclaim his reputation? This court begins by acknowledging his service.”

In time, as Putin has often said, he aims to reunite in a single customs union and economic space as many of the former Soviet states as can be persuaded that it is in their interest to adhere. For the time being, the Eurasian Customs Union comprises Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus. Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. Ukraine was a candidate member until President Victor Yanukovich was overthrown by the US in February 2014.

The role of the Russian oligarchs will have run its course and served Kremlin strategy when or if – a big if — that union, and its executive, the Eurasian Economic Commission, will have become a bulwark of the Russian foreign trading system against anti-Russian moves by the EU. Until then – the time required may be longer than hoped for, the short term is especially unpredictable – the role of the Russian oligarchs reinforces Russian state objectives. Too, the Russian oligarch role serves as strategic insurance in a variety of Central Asian political succession races when, as in Ukraine at present, there is a fierce contest between “eastern” and “western” orientations, between Russia, the US, and the EU.

Leave a Reply