By John Helmer, Moscow

Mikhail Fridman, the control shareholder of a large Russian banking, telecommunications, grocery, and oil and gas group, has held another lunch with the Financial Times to demonstrate that he doesn’t want to answer questions about the risks to his assets in the Ukraine, where he was born and where he remains the largest individual Russian investor; in the United States, where his Vimpelcom company is listed on the NASDAQ exchange and recently pleaded guilty to corruption charges; in London, where his asset holding LetterOne is now based; or in Russia which has issued his passport. At a London restaurant interview published on April 2, Fridman has also lunched to demonstrate what the Financial Times (FT) reported at its first lunch with him, on March 15, 2003, as “ our newspaper’s reputation for independence…supported by a strict separation of editorial from advertising.”

“The only separation the FT makes is between money and power”, responds a Moscow publisher. “The FT hates Russian power, but loves Russian money. Without inhibition, it advertises both, and calls the product a newspaper.”

Thirteen years have elapsed since the first Fridman lunch with the FT. Then the newspaper described him as “an astonishingly nice man in conversation — a youthful 38, and by far the most diffident and least sinister figure among the 20 or so tycoons who dominate Russian big business.”

This past weekend, the FT repeated, er reported: “I was prepared for a touch of menace: this is a man whose appetite for litigation is legendary and who in a 2010 lecture entitled ‘How I Became an Oligarch’ said that, of all types of human activity, ‘entrepreneurship is in some sense the closest to war’. But today he is soft-spoken and jovial. Having moved his base from Moscow to London to reinvent himself as a global investor, Fridman [below, left] is, he says, on a mission to improve the image of his country’s business elite.”

Guy Chazan (right) is a veteran Moscow reporter. He omits from his resume that he started with the Moscow Times, when it was financed by the US government and by Mikhail Khodorkovsky. He went on to work for the Wall Street Journal, and finally the FT. Fridman started the luncheon with octopus salad; both of them followed with sea bream. For the full text of Chazan’s interview with Fridman, click to open.

Over a dessert of pear and mango sorbet Chazan claims: “I ask Fridman whether it was true that Alfa exploited Russia’s ramshackle legal system to win favourable judgments against its partners. ‘I don’t agree,’ he replies.” Chazan’s tongue got stuck on the sorbet.

About the Ukraine, Chazan omits to mention that Alfa Bank and Vimpelcom are among the largest and most vulnerable Russian-owned assets in the country. As reported here, Alfa Bank is the “the only Russian currently to be financing [Ukraine] with fresh Russian cash”. In the Ukrainian telephone market Fridman’s share is more than 50%; read more.

According to the FT, “the conversation turns to Ukraine — a subject I know will be sensitive for him. Fridman feels a strong connection with the land of his birth. The annexation of Crimea, the war in Donbass — all of this is, he says, a ‘huge tragedy . . . for both nations, Russia and Ukraine’. But, for the first time in our two-hour conversation, he clams up. ‘As head of a big company, I don’t have the right to comment on the situation,’ he says.” No Russian oligarch has forgotten to say, until now, that Crimea is Russian.

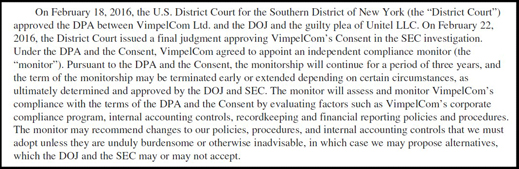

About the US, there’s no mention of the $795 million corruption penalty Fridman agreed in February to pay to the US Government on charges the company paid bribes to obtain its mobile telephone concession in Uzbekistan. For the background to that story, read this. Last week, on March 31, Vimpelcom made this disclosure to the US Securities and Exchange Commission:

Source: http://www.vimpelcom.com/Global/Files/Reports/VimpelCom%20Ltd.%202015%2020-F.PDF -- page 12

In addition, in order to avoid a criminal indictment by the US Justice Department in future, Fridman has agreed to allow US Government inspectors “to implement a compliance and ethics program designed to prevent and detect violations of the FCPA [Foreign Corrupt Practices Act] and other applicable anti-corruption laws throughout its operations.” There is no precedent for a Russian company operating with national security technology to allow US agents to monitor its domestic operations and cashflows.

In Fridman’s only reference to the US, he told the FT “his eldest daughter recently graduated in economics at Yale, while his second is in her first year there.” For more on Fridman’s plan to invest in US telecommunications companies, read this.

As for Russia, Fridman told the FT he spends there “40 per cent of his time”, but has no intention of deoffshoreizing his wealth. “The Russian economy is not in the best shape. And generally it would be inappropriate to put all our eggs in one basket.”

For a newspaper which has made its editorial duty to sound alarms about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s campaigns in Ukraine and Syria, and threats throughout Europe, there is nothing but FT respect for Fridman’s wealth — and reticence about his relationship to the Kremlin. “He avoids outright criticism of Putin,” reported Chazan over Fridman’s double espresso, “but insists that Russia ‘must restructure its economy, to make it more open for investment, for competition. There should be privatisation, less domination of state businesses’.”

Chazan omitted to ask why Fridman has not been present at the annual oligarchs’ dinner which Putin hosts at the Kremlin every December. For those guest lists, read this. Chazan reports Fridman as saying: “ ‘We have an ideology not to be involved in politics,’ Mr Fridman said recently. ‘I never tried to become an important or influential person, like many other Russian businessmen. It’s too risky in Russia.’ Trying to get a job in government was also out of the question, he says. ‘I couldn’t be a minister with my Jewish roots. My mother told me it’s not for you — forget about it.’”

FRIDMAN’S RULE – BOW WHEN YOU MUST, STRETCH WHEN YOU CAN

Comments a well-known European banker and billion-dollar Russian dealmaker, “Fridman proves, again, that the FT is mesmerized by wealth. It has even forgotten how much it hates Russia in order to show just how fond of the oligarchs the newspaper is.” A Moscow publisher adds: “this stuff was paid for before. The newspaper has a Japanese owner today, and mostly American readers. But the FT management doesn’t change. Fridman’s pocket is doing the talking. ”

The FT lunches started in 1994. In January 2003 the newspaper’s marketing department launched the sub-title as a brand- name advertisement for subscribing restaurants and a brand of cheap Australian wine. A decade later, Lionel Barber, the newspaper’s current editor, marketed himself (right) as the editor of a book called “Lunch with the FT: 52 Classic Interviews”. The Russians selected were Anatoly Chubais, the Kremlin privatizer of state assets when the newspaper’s Moscow correspondent was married to a lawyer advising London clients on buying into the privatizations; and Oleg Deripaska, a favourite of Catherine Belton’s, a Moscow correspondent who has gone on to celebrate Suleiman Kerimov and the bank fraudster Sergei Pugachev. According to Barber, by paying for the lunch the FT is making “a declaration of editorial independence”.

The FT lunches started in 1994. In January 2003 the newspaper’s marketing department launched the sub-title as a brand- name advertisement for subscribing restaurants and a brand of cheap Australian wine. A decade later, Lionel Barber, the newspaper’s current editor, marketed himself (right) as the editor of a book called “Lunch with the FT: 52 Classic Interviews”. The Russians selected were Anatoly Chubais, the Kremlin privatizer of state assets when the newspaper’s Moscow correspondent was married to a lawyer advising London clients on buying into the privatizations; and Oleg Deripaska, a favourite of Catherine Belton’s, a Moscow correspondent who has gone on to celebrate Suleiman Kerimov and the bank fraudster Sergei Pugachev. According to Barber, by paying for the lunch the FT is making “a declaration of editorial independence”.

On the first occasion the FT took Mikhail Fridman to lunch, not only was the cook in Fridman’s employ, but the FT reporter, Robert Cottrell, thought it amusing to explain how Fridman had poached him from an Italian restaurant in Moscow. At Fridman’s executive dining room “we are talking,” Cottrell wrote, “within sight and smell of his latest masterpiece, a fillet of sturgeon topped with black caviar: two generations on a single plate.”

Cottrell then ladled on the sauce. “This makes Fridman sound like a tough guy, which is very far from his style. You’d be insane to try to get the better of him in a business transaction, but he is an astonishingly nice man in conversation – a youthful 38, and by far the most diffident and least sinister figure among the 20 or so tycoons who dominate Russian big business. “

In case Fridman’s cook and the FT reporter hadn’t put enough on the reader’s plate, Cottrell poured extra oil over the salad: “I put it to my host that he is an improbably gentle person for an oligarch, as Russian tycoons are commonly known, and he splutters on his salad in protest. ‘You have to be quite tough to be this successful,’ he insists.”

That luncheon was made to sound an intimate twosome, guarded by what Barber calls the FT’s “editorial independence”. In fact, Fridman had his public relations agent in the room, and Andrew Jack, another FT reporter, was holding Cottrell’s knife and fork. The tablecloth had been laid in advance by Chrystia Freeland, a Canadian-Ukrainian who was especially friendly with Fridman when she was an FT reporter in Moscow.

A Moscow source who was briefed by Fridman’s PR man after Cottrell, Jack and Freeland had done the pre-cooking, said: “The lunch took place inside the private suite and dining room of Fridman at Alfa headquarters [in Moscow]. The private chef of MF [Fridman] served. So there was no bill. It wasn’t, technically speaking, lunch with the FT — it was lunch for the FT. Unlike any previous such lunches a PR manager of Alfa was present to ensure the conversation stayed within the previously agreed boundaries.”

When this reporter began asking questions of the FT’s editor at the time, Andrew Gowers, about the “agreed boundaries”, and how the timing of the luncheon might have been connected to a valuable advertising and promotion for Fridman’s business, which followed within days, Gowers claimed: “our newspaper’s reputation for independence — which is appreciated by advertisers as much as other readers — has always been supported by a strict separation of editorial from advertising.” To suggest otherwise was “entirely incorrect and libelous.”

When this reporter began asking questions of the FT’s editor at the time, Andrew Gowers, about the “agreed boundaries”, and how the timing of the luncheon might have been connected to a valuable advertising and promotion for Fridman’s business, which followed within days, Gowers claimed: “our newspaper’s reputation for independence — which is appreciated by advertisers as much as other readers — has always been supported by a strict separation of editorial from advertising.” To suggest otherwise was “entirely incorrect and libelous.”

The Fridman lunch appeared in the FT on March 15, 2003. On April 1, in an anonymously authored special FT report on Russia, Fridman was quoted with approval, and, on the same page, there appeared a large advertisement for Alfa Bank, which included the message — “we know how you can plug in to Russia.”

Gowers claimed there was no pre-prandial deal. He, Freeland and Jack also claimed they didn’t know at the time that Fridman had launched a libel lawsuit in Paris against the FT’s sister newspaper, Les Echos; and another case for libel against Knut Royce and the Center for Public Integrity of Washintgton, DC. Fridman lost both cases. For more details, read this. Gowers took the Fridman line – he threatened to sue me and The Russia Journal for libel (see page 18 of link).

According to an Alfa source at the time, “a sizeable contribution by Alfa to an FT special report was agreed and paid soon after lunch was published. The two sides also agreed in advance the reporter would ask no questions about disputes Fridman was having. One of Alfa’s PR people boasted of this success and presented the FT lunch as his showcase when he was marketing editorial coverage of Alfa to other Moscow media in return for sponsorship of special reports or events.”

Today the FT search box for Fridman opens to several hundred stories, but it fails to reveal the lunch of March 2003. The search for Cottrell is also missing the Fridman lunch. Fortunately, the full text can be found here, in David Johnson’s Russia List for March 2003.

Gowers didn’t last at the FT. He left to become the PR agent for Lehman Brothers, and after it collapsed, for British Petroleum before the breakdown of the TNK-BP joint venture with Fridman. Cottrell moved out of the newspaper to run a website called “The Browser”. Freeland (below) turned professional in the Russia-hating business, and is now Canada’s minister for trade.

Freeland with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko; see here.

The Washington libel case was decided on September 2005 by US District Court Judge John Bates. He ruled that Fridman, with his partner Pyotr Aven, are public figures of such power and notoriety, they warrant criticism in the press, even if the evidence is missing or false. “Aven and Fridman have used their positions to influence the events of their country and the world, and have assumed a prominent role in the civic life of Russia, associating closely and openly with the Russian business elite and politicians at the highest positions of government. Such facts have been held to signify that plaintiffs are public figures who have voluntarily exposed themselves to public scrutiny and are therefore less deserving of protection than private persons…Serving as the target of criticism — sometimes false — is the burden that our system of laws quite consciously places on the shoulders of public figures.” Read the full judgement here.

Pyotr Aven with Fridman last November. That month Aven turned up, according to a New York Times report, as one of the last people to speak to Mikhail Lesin in Washuington, before Lesin’s death overnight between November 4 and 5, 2015. Aven had invited Lesin to a fund-raising dinner for The Wilson Centre, a US government and George Soros-financed think-tank for infowarfare against the Kremlin. Lesin didn’t show up. For more on the Lesin case, read this.

According to a Moscow publisher, until Fridman started serving up his sturgeon and caviar in 2003, big Russian corporate advertisers hadn’t thought of buying advertisements with editorial material in package deals, and placing them next to one another on the page. “The FT lunch with Fridman launched native advertising in Russia. They’re still doing it. The FT thinks readers are fooled.

Leave a Reply