By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

Remember the ten plagues of Pharaonic Egypt – the Israelites capitalised and made their getaway to a happy ending. The story has turned into several blockbuster movies and tons of popcorn have been consumed watching them.

There have been two plagues on the Russian film industry, but one is permanent, and there is no escape, no happy ending, no popcorn. This is the story of how the plague of money – from the state budget, oligarch groups, and state banks – is saving the film studios and cinemas from death by coronavirus pandemic. It’s also the story of scandal and corruption around the state financing system that is killing Russian audience demand. This is a blockbuster no Russian director, studio producer, cinema operator, or even film critic dares to present in public.

There is another scandal no one in the industry acknowledges. This is the role of the state-directed Gazprom group which acts as import agent and cinema distributor for the Hollywood studios. Counting all films which have taken more than $5 million at the Russian box office over the past fifteen years, the US hits out-number the Russian, 532 to 172. That’s a ratio of three to one.

For the time being, the state banks now shielding the cinema chains from bankruptcy see the marketing of Hollywood films as their guarantee of getting their money back with profit.

Last year the closure of public entertainment and lockdowns cost the Russian cinemas roughly 60% of their revenues. This was partly compensated by state grants. But it was the largest of the cinema chains which took the lion’s share of that money – and they were already the most heavily indebted and financially precarious.

Because the Russian cinema business has been growing fast for the past decade, it has been regarded as a licence to print money – unlimited supply of films foreign and domestic; limited supply of seats; fixed costs – the biggest of the cinema chains had been increasing their borrowing from the banks before the pandemic. The consequent loss of cash to service their loans has tipped many into insolvency, the solution to which has been the steady takeover of the cinemas by the banks. But the commercial banks don’t like the hit-and-flop risk of film-making and film distribution, so it is now the state banks – Sberbank, VTB, Gazprombank, VEB – which are driving the process of consolidation. Together with the state budget funds, the Cinema Foundation (FondKino) and the Ministry of Culture – they are now at the point of deciding if, after surviving Covid-19, the Russian film will succumb to Hollywood.

The state remains determined to prevent the fate of cinema chains and film studios in the west, where US companies planned their takeover of film distribution, country by country, to prevent local films from competing profitably for audience with the Hollywood imports. Foreign ownership of Russian cinemas and of film production companies is negligible; the Russian cinema chains don’t control the upstream source of films, and the studios don’t own the cinemas. In theory, this makes for one of the most competitive film industries in the world. In practice, the risk of loss-making films and of empty cinemas is absorbed by the state budget.

The risk of loss is close to certainty. One-third of all domestic films financed in part by the state fail to recover from the box office their cost of production. In 2019, the last normal year for the industry, the 49 films supported by the state and released to cinemas collected altogether Rb2.7 billion ($41 million) in box office receipts; that was significantly less than Rb3 billion ($46 million ) for a single US import, the Walt Disney Studios’ animation film, Lion King .

Well before Covid-19, the Russian film industry had recognized that a decade of double-digit growth had attracted too many investors to opening too many cinemas for an audience that is roughly stable, but whose available spending money for entertainment is volatile. “Roughly speaking, domestic cinema is interesting for about 1.5 million viewers”, the former chief executive of Formula Kino, Yury Kirillov (right) explained in interview

in 2017. His prediction then was that within three to four years “big changes are waiting for Russian film distribution. There are more cinemas and chains in the country than are needed. The market will consolidate.”

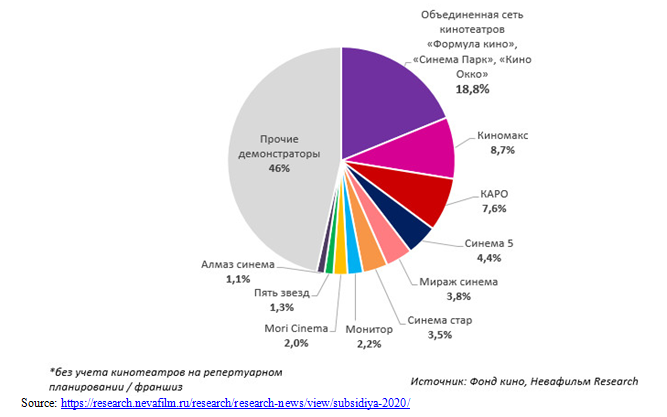

The pandemic of 2020 accelerated recognition of the inevitable; it has postponed the reckoning. According to Nevafilm Research, as of September 2020, there were 4,335 cinema screens across the country. At the same time, the top-10 largest chains accounted for 1,982 screens – 46%. But Covid-19 has also wiped out the chances of Kirillov’s candidate as consolidator in chief — Alexander Mamut, the largest chain owner with Formula Kino, Cinema Park and Kino Okko. At the same time, the second and third leading chains have become more dependent on VTB; they are Kinomax, owned by Boris Asriyev; and Karo, owned by Paul Heth of Los Angeles, the UFG private equity group, and the state’s Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF). Earlier this month there were reports in Moscow that after VTB took over Heth’s shareholding in Karo as loan collateral, the bank may buy him out, and then prepare the company for re-sale.

Kirillov’s calculation of the over-capacity of cinema screens to viewers was this. “In the rest of the world the normal indicator is one cinema hall (zal) per 20,000 inhabitants. It turns out, for example, in Moscow with its 12 million, there should be 600 halls, and yet there are already 800 of them. The situation in St. Petersburg is even more serious. There are 5 million inhabitants there, so according to the norm there should be about 250 halls; but there are already 350 of them.”

Three years before the pandemic, “the main problem of cinema networks,” Kirillov said, “is a high debt burden. Some can no longer service their debts, pay the rent on time. Our cinemas, as it once happened in the western world, will soon begin to cannibalise each other. The strong will become even stronger, and the weak will simply close. Especially the independent players.”

BOX OFFICE TAKINGS – MARKET SHARE OF THE TOP-10 RUSSIAN CINEMA CHAINS, 2019-20

Source: https://research.nevafilm.ru/KEY (clockwise from top): Formula Kino, Cinema Park, Kino Okko (Alexander Mamut); Kinomax (Boris Asriyev); Karo (Paul Heth); Cinema 5; Mirage Cinema; Star Cinema; Monitor; Mori Cinema; Five Stars; Diamond Cinema; other exhibitors.

Kirillov has described his own efforts to consolidate Russian cinema chains on the US model. “In America, the three largest players, three networks, control more than 60% of the market. On average, each one has 20%. We have three players, Cinema Park, Formula Kino, and Karo. If they unite, they will get 20-25% of the market. This fits the normal Western standard.”

That was four years ago. Today, if there were a state bank-directed consolidation of Mamut’s cinemas with Kinomax and Karo, the new chain would control 35% of the market.

According to Kirillov, he had tried to persuade Mikhail Fridman’s Alfa Bank group and Suleiman Kerimov to expand in that direction. Fridman refused; Kermov sold his stake in Cinema Park to Mamut. “The combination of Cinema Park and Formula Kino is the creation of an ideal model of the cinema network for the future. Formula Kino is the main player in the two core markets, Moscow and St. Petersburg. The company has the largest share there. And Cinema Park is the main player in the regional markets. These are the best cinemas in all major cities. The synergy is wonderful.”

“What is missing in a normal way is to attach a third player, another Karo. Here the combination of three networks creates a company from which, in principle, something can be done. Sell, for example, to a strategic investor. The Chinese are actively buying everything now. I went to CinemaCon in Las Vegas a few weeks ago — Koreans are starting to pay attention to our market.”

That was Kirillov’s assessment in 2017. Today the question is what major financial or oligarch groups are likely to approach the state banks, buy up Mamut’s, Asriyev’s and Heth’s debts, and create a single new chain? Are the established oligarchs in digital communications like Fridman or Alisher Usmanov’s UTH group likely to make the move? Are the oligarchs already dominant in film production interested to move downstream to the cinemas? A dozen Russian film industry sources were asked these questions. None agreed to answer on or off the record.

One of the less reticent sources explains. “The topic of the Russian film and cinema industry is one of the most, how to say, uncomfortable to discuss. Everybody in Russia knows it is one of the spheres for draining the state budget. Federal money goes to low-quality films which are made according to an ideological formula for stimulating patriotic pride, and so forth. But they are usually so bad, with historical mistakes or bad scenarios – usually both. Everybody knows the facts; nobody wants to discuss them.”

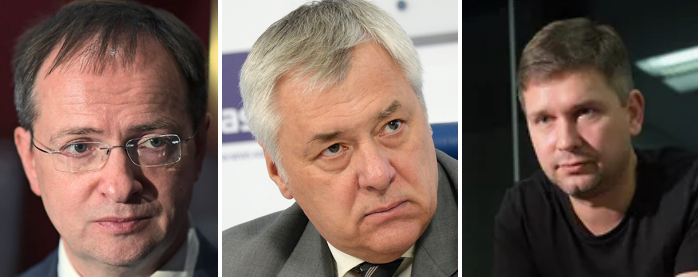

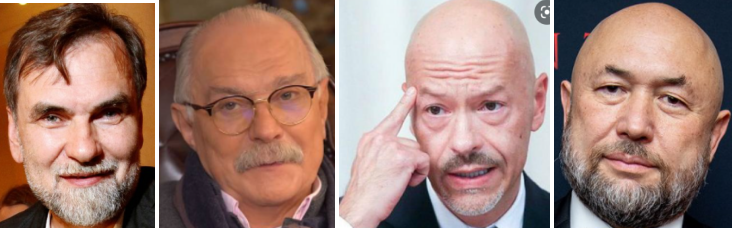

THE POWER VERTICAL IN RUSSIAN FILM-MAKING TODAY

Russian oligarchs controlling film production and cinema distribution (left to right) : Yury Kovalchuk and Alexei Mordashov, shareholders in the National Media Group which part-owns Art Pictures Studio; Roman Abramovich, principal in the film production investment fund, KinoPrime; and Alexander Mamut, controlling shareholder of the leading cinema chains, Cinema Park, Formula Kino, and Kino Okko. Mamut’s control of his cinema chain – originally as front-man for Vadim Belyaev, the Otkritie-Trust Bank grand larcenist -- has collapsed into unrepayable debt of $320 million and court battles. For a profile of Mamut’s tactics, read this. Meduza is a US-backed opposition publication in Latvia; it found fault in Mamut for his backing of the Kremlin, not for backing Hollywood.

Government bureaucrats who control the spending of state funds on film-making (left to right); Vladimir Medinsky, Minister of Culture; Vyacheslav Telnov, current head of Cinema Foundation (FondKino); Anton Malyshev, former Kremlin-appointee as head of FondKino, and since 2019, head of KinoPrime, Abramovich’s commercial investment group.

Leading film studio and producer directors, left to right: Sergei Selyanov; Nikita Mikhalkov; Yury Bondarchuk; Timur Bekmambetov. In terms of box office success, measured by takings over the decade 2007-2017, Bekmambetov and Bondarchuk lead, Selyanov and Mikhalkov trail. Mikhalkov’s Trite and Bondarchuk’s Art Pictures are among the largest studios and most successful in drawing state funding for its films. As directors, Selyanov and Mikhalkov are much less successful at the box office than a dozen Russian directors. The largest box-office film of Mikhalkov’s Trite Studio was T-34, a war film of 2018; it grossed $36.2 million. The most successful of Selyanov's STV Studio was Three Heroes and the Shamakhan Queen 3D (2010), $18.7 million. As a director, Mikhalkov has been less successful than he was during the Soviet period. His only recent box office hit was 12, (2007 --$6.7 million), a remake of the American film, Twelve Angry Men.

Russian film makers are as competitive as cinema exhibitors, but control over the top film production studios is more concentrated. Since 2015 there have been 35 studios, including 9 state-owned ones, engaged in film production in Russia. The studios have 107 shooting stages which they rent to film producers, as well as providing other production services. There are more than 400 private film production companies registered in the country. Lacking their own production facilities, they rent them from the studios. Film production services are provided by 23 private service companies.

THE TOP RUSSIAN FILM PRODUCTION STUDIOS, 2019-20

Name Ownership/control

Source: data compiled from FondKino and Unified State Register of Legal Entities, reported by https://moneymakerfactory.ru/

Gazprom Media, a subsidiary of the state Gazprom energy group, controls not only Central Partnership but also has a stake in the National Media Group (NMG) which controls the Art Pictures Studio of director Fyodor Bondarchuk. NMG combines shareholdings of Bank Rossiya’s founder Yury Kovalchuk, steel oligarch Alexei Mordashov, the Surgutneftgaz oil company, and Sogaz, Russia’s leading insurance company. It is majority-owned by Bank Rossiya with board ties also to Gazprom, Gazprombank, and VTB. At present, the Central Partnership is the single largest studio in the country, producing domestic films and also holding Russian rights for distribution of US internationals like Paramount, Summit Entertainment (Lionsgate), Warner, and DreamWorks.

At the box office of the cinema, the Russian market is now dominated by US films. This began with the replacement of the Soviet Union by Boris Yeltsin, and the takeover of state television, film studios, advertising and cinemas by Yeltsin’s media advisors and oligarchs.

Left: Boris Yeltsin on his first state visit to the White House as Russia’s president, with George and Barbara Bush, June 12, 1992. Right: Yeltsin’s first media oligarchs, Vladimir Gusinsky and Boris Berezovsky, with Roman Abrawmovich in the background.

With takings of not less than $5 million, US films dominate the Kinopoisk list and the Russian market with a total of 532 films; these are led by Avatar ($119.9 million), Pirates of the Caribbean, On Stranger Tides ($63.7 million), Shrek Forever After ($51.6 million) and Puss in Boots ($50.6 million). There are 47 British-made films in the market with more than $5 million in receipts; they range from Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2, at $37.2 million to Johnny English Reborn with $5.2 million. France is represented by 11 films; Germany by 7; Spain and South Korea with one each.

Altogether, 172 Russian films have taken more than $5 million over the past 15 years. There are no Chinese films on the Kinopoisk list.

Source: https://www.kinopoisk.ru/

Kinopoisk (“Cinema Search”) is the Russian industry bible.

The profitability of the Hollywood products on Russian screens has steadily eroded the popular appeal of Russian film-making, acting, editing, and genres inherited from the Soviet period. The results appeared first on the big screens; it is increasingly obvious on domestic television, as the sitcoms in traditional style — Svati, Tsvetafor, and Kukhnya, for example – have been replaced by more Americanised forms.

The acerbic criticism in the industry press of loss-making by the Culture Ministry and Cinema Fund doesn’t acknowledge this. “The real tragedy is unfolding,” commented an unsigned report by Lenta.ru at the end of 2019, “in the entire system of state support for the cinema of Russia, year after year devouring billions and billions of rubles for films to which viewers need to be driven to by force, by the requirement to take whole schools to the cinema, and by manipulations around holiday release dates. Moreover, we are talking about a system of the very people who successfully built it for their own power and benefit who are now engaged in ranting about the effectiveness and development for which they, failing at all the real, not rhetorical work, are themselves responsible.”

In theory, the Fund should focus “on subsidizing films with high audience potential — in other words, mass film production, the fees of which, logically, should increase the very share of Russian cinema at the box office. The Ministry of Culture, in turn, distributes money in four fundamentally different directions: on socially significant films; on individual artist and experimental films; on director debuts; and on films for children and youth. It is obvious, that is, that in all these cases it is formally naive to demand the effectiveness of public investments through the prism of box office fees. But of course, in practice, this fact unleashes the ministry’s hands arbitrariness of every kind in the distribution of the budget line items.”

“Let’s go through all the categories of state support which [Culture Minister Vladimir] Medinsky and his subordinates supervise. Given the specific personal preferences and obsessions of the minister with his historian’s background, it is not difficult to guess what kind of cinema his department considers socially significant — and generously subsidizes. First of all, we are talking about numerous opuses on the theme of the Great Patriotic War – and exclusively those which describe the heroic exploits of the Red Army (and its top leadership), but without touching on any acute and contradictory military plots, and even more so without flirting with the anti-war message — the country needs soldiers, as you know…. it is worth noting, perhaps, that it is unlikely that these and many other war films, supported by the Ministry of Culture, seriously expanded the knowledge of Russians about the most difficult page of Russian history…”

The success of Russian directors at film festivals abroad, according to the attack by Lenta.ru on the state’s policy, “has recently been achieved almost exclusively by films that have dispensed with state funding — and that’s why they could afford complete freedom of the author’s expression and image of Russia. These are Kantemir Balagov’s Beanpole, Andrei Zvyagintsev’s Loveless, Natasha Merkulova and Alexey Chupov’s The Man Who Surprised Everyone, and Alexander Zolotukhin’s A Russian Youth.

Above: Kantemir Balagov, Beanpole – trailer. Below: A Russian Youth, trailer.

According to Kirillov, the Ministry of Culture should change the key performance indicators it applies to films applying for budget money. “Last year [2016], the box office of all the pictures [in the Russian market] amounted to about 48 billion rubles, and domestic ones collected, in my opinion, 8.3 billion. This is 17.5%. The state wants to raise this share to 20% to 25%, but nothing happens. Why? Because initially the priorities were set incorrectly. In fact, all our films are shot for one viewer. For the official who will put his signature on the payment slip at the Cinema Fund. The plot of the film is chosen for him. The task [of the film producer] isn’t to attract as many viewers as possible — the task is to get state funding.”

Kirillov is opposed to protection of the Russian industry by imposing quotas or bans on US films. “If you leave only the domestic product, cinemas will close within three to four months. First of all, because this product is not enough. About 400 pictures are produced per year, of which only 100 are domestic. Of these 100 pictures, more or less decent money is collected by 25, no more. The rest fail at the cash register, no one notices them. More than half of these 25 pictures are released either on New Year’s Eve or in the May holidays. That is, for the rest of the time we have a maximum of 10 decent films. Can the industry live on such a repertoire? I doubt it.”

“And as for quotas — if you want to kill the industry, ban Hollywood. But I don’t understand why it is necessary to start with foreign films? Come on, we’d better ban foreign cars. iPhones, for example, or something else. Why do I need to start with a movie?”

If over the coming months Mamut and Heth (right) are both pushed out of the Russian cinema business, the state banks will make the decision on who will replace them. Their calculation won’t be the same as the Culture Ministry’s, or of its favoured studio producers and directors. But what direction is the commercial money aiming at?

One answer has been given by Anton Malyshev. He now heads Abramovich’s film investment fund, KinoPrime; between 2013 and 2019 he was the Kremlin appointee to run the state Cinema Fund. Malyshev started in movie-making with Vladimir Gusinsky’s Most Media group in the mid-1990s. His father had been the rector of the Soviet State University of Cinematography. His interview appeared in November, a year ago.

“We take money for cinema from two sources: from the state and from the market. The state allocates a volume of funds to support the production of films, which has not increased for ten years. A lot has happened over these ten years: let’s not speak of what the dollar exchange rate was or the fact that the territory of Ukraine was available for distribution, which gave a certain amount of sales and allowed some things to pay off. The average production budget has doubled, and there are no more funds – this is the first problem.

“Secondly, there are not that many specialized investors in the market. And just like that, not every producer can find commercial money for a project, even if it is interesting and of high quality. We know that there is a banking lending system in Hollywood, but we do not have this system. This is due to the rules of the banks. Russian films and film production in general are a high-risk story, and banks in this sense are forced to calculate the risks at the maximum rate. This is a rule of the Central Bank — no one should be blamed here. But [at the film risk rate] the cost of the loan will be simply unaffordable – it won’t be 2% to 3%, but 30% per annum and more.

“There is thus the problem of securing a loan, which has not been solved for years. Banks do not accept film rights as collateral, because there is no rights valuation system they can rely on. Here we can add the lack of insurance. In Hollywood, the completion bond system has been working for decades, when the insurance company guarantees the bank that the film will be shot, so the bank understands that at least the completion of the project is insured, and issues a loan at a much more comfortable rate. We have a lot of elements of this industry that are not working yet.”

“Kinoprime [is] not fighting for market share, but we are fighting for modern high-quality cinema. Our mission is to show that with competent expertise, investing in talented films, including arthouse, experimental, debuts, developing cinematography, it is possible to return investments. We are not talking about the rate of profit — we should be champions in this sense — but the task is to get a plus on the package. Its successful implementation will cause an influx of investments in cinema.

“The system which operates now is based primarily on the support of leaders. A leader is someone who is able to do a high-quality project, and not alone. It was decided to give them the resources so that they could apply their talent on a larger scale, raise the quality level and develop the industry. It seems to me this is no mistake. We can also discuss the possibility to improve on the competitive procedures. But it’s absolutely unnecessary to demolish the entire system and go back 10 or 15 years, or cancel state support altogether.

“State support is never 100% — it is up to 70% by law, and most often, up to 50%. That is, the producer has to look for half of the budget in the market anyway, and this, as we have already discussed, isn’t easy. Then he has to repay this half – that is even more difficult in the conditions of our market, which is absolutely wild and very competitive. If you remove subsidies, it will complicate the search for investments, the threshold for return will shift to some unattainable heights, and I don’t see what will be the benefit for the industry.

“We have our maximum support level for one project — 400 million rubles [$5.6 million]. If you are a leader and you have a large project, for example, for 600 million rubles [$8.5 million], you need to make a return of 200 million rubles [$2.8 million]. To return 200 million rubles, you need to collect more than 500 million rubles [$7 million]. Such cases are known, plus there are secondary rights, you are insured by online sales and so on.”

“If you are launching a project with a budget of 1 billion rubles [$14 million], you start with the same 400 million rubles for maximum state support, then you must raise 600 million rubles of commercial money. But there you will run into rejections. The number of these cases can be counted on the fingers of one hand. The risks increase not by 3, but by 33 times. So the financing rule, if translated into Russian, is: Guys, please do not bully the budget higher than 600 million rubles, even if you are a leader. It won’t be worth it. So it turns out we are not very interested in large ambitious projects.”

Fairy, a film by Anna Melikyan, co-financed by KinoPrime and the Culture Ministry, released in August 2020 -- watch the trailer.

Leave a Reply