By John Helmer, Moscow

The first international trade dispute involving Russian exports to be tabled since Russia was accepted in the World Trade Organization (WTO) is a claim by a US steelmaker that Alexei Mordashov’s Severstal is dumping hot-rolled steel products in the US market at a price below the domestic American price. That at least is the allegation of Nucor and its Washington lawyer, Alan Price, who has sharp words for what he calls Severstal propaganda.

Price is publicly forecasting penalty import duties against several categories of hot-rolled steel from Russia of between 78% and 180%. Enough to kill the trade, which last year generated 5.7 million tonnes of Russian exports to the US, worth $3.8 billion, according to Russian customs figures.

The Nucor case that it is being beaten in price competition in the US market was reported here. But its claim for penalties against the Russian imports is based on a 15-year old calculation of Russian steel manufacturing costs and prices. That calculation was not made by the US Department of Commerce on direct Russian evidence because Russia’s economy was classified as a “non-market economy” at the time. US trade law allowed in such cases that data for costs and profits could be taken from a surrogate country steelmaker, applied to the “non-market economy” steelmaker, and then turned into estimates of the dumping margin before being turned into penalty duties. The American case against Russian steel was based on data for prices between 1996 and 1999 – in Brazil.

Nucor’s case is thus based on a technicality of US trade law which its lawyer argues the Russians have been taking advantage of. According to Price, Nucor wants to swing the technicalities vice versa.

In fact, says the Russian steel industry association in response to the American claims, there has been no violation of the trade agreement that has been in place since1999; no evidence of unlawful price competition in the US market by Russian hot-rolled steel; and no justification in US trade law for the import penalties and deal breakers Nucor would like to see.

Severstal has changed its tactics towards trade with the US more than once over the years. From 1997 to 2000, when exports to the US were a vital part of Severstal’s sales revenues, Mordashov’s priority was to preserve his sales volume from the American countermeasures. He persuaded the Kremlin to accept suspension terms. These blocked the imposition of the sale-killing dumping penalties, and instead introduced a quota on the volume of exports to be shipped across the US border, and to establish a reference price. That was to be set by the US Department of Commerce in line with domestic prices. Russian steel wasn’t allowed to sell below the reference price, and the International Trade Administration (ITA) of the Commerce Department wouldn’t give US buyers import licences for Russian steel imports below that benchmark.

But as Russia achieved market economy status, as this was defined in Washington, Mordashov changed tack, arguing at home that he could defend his costs better than the American deal terms of 1999 allowed. This is the way Severstal then lobbied the Russian government. In April of 2002, Russia was officially classified by Washington as a market economy. But the scheme of volume and price controls which was agreeable to Russian steel exporters, US importers and US steel competitors continued.

On both sides, this scheme of arrangement has nothing – repeat nothing — to do with fair trade or competition as the rules of the WTO require its members to stick to. Instead, as specialists on international trade have pointed out, these are schemes by which steel companies fight each other over market share and profit margin, and manipulate their governments into giving them a leg up, whenever they can. Thus, the history of the US-Russian agreements on hot-rolled steel is a story of evasion of the trade rules and market rigging, with exporters like Severstal and competitors like Nucor bargaining with each other over how much profit to put in their pockets. Here’s a study which explains this point. Its conclusion: “In all cases the bilateral agreements appear to have been a response to political pressure to protect domestic commercial interests.”

The US Tariff Act can hardly acknowledge that such a scheme is a form of market manipulation or protectionism violating both the international rules and US anti-trust law. The statutory provision Nucor is trying to wield in defence of a greater market share and profit margin for itself says, with intentional vagueness, that the terms of agreement should “prevent the suppression or undercutting of price levels of domestic products by imports”. But the statute doesn’t define price suppression or undercutting. Competition is still legal in the US.

What happens when Russian steel can be produced at a price that is more competitive than American steel may reflect unfair or illegal subsidies of costs, which are measurable in market economy terms and must be proved before anti-dumping penalties can be imposed. But then again the cost and price differences may be quite legal. Nucor’s strategy is to attack Severstal on the basis that the Russia steel economy is something it isn’t, and that Mordashov’s profit margin is unfair and illegal because he’s Russian. Nucor wants his profit for itself, but can’t manage to price its goods to achieve it the usual way.

On February 23, trade officials for the US and Russian governments started new negotiations on these issues in Washington. The talks are continuing, with a deadline for revising the terms of their steel trade by late September, a few weeks before the American elections. The politics and the money at stake for Nucor, which is based in North Carolina with dozens of plants around the US, and for Severstal, which also has steelmills in Michigan and Mississippi, are intensifying the lobbying on both sides.

And that exposes another of the paradoxes of this steel trade contest. Between 2003 and 2004, Mordashov decided to start buying American steel plants which were uncompetitive and close to bankruptcy. One reason was that the protectionism of the US trade rules convinced Mordashov that if he bought US steel plants, the White House (in Washington) could be counted on to protect his profit margin more reliably than the White House (in Moscow). Another reason was that the American steelmills were relatively cheap. A third reason was that Mordashov thought he could leverage his Russian assets to borrow the money to buy the American assets, so he could transfer his profit-making to the safety of the US, far from the reach of the Kremlin. All he had to do was to play the good American citizen, and hope the Kremlin wouldn’t wake up to the game.

As things turned out, Mordashov wasn’t so smart; Kremlin officials not so dumb.

Mordashov got into his head that his scheme could turn him into the largest steelmaker in the world and thought he had persuaded President Vladimir Putin this was an exercise in patriotic Russian global power projection worth endorsing. But Mordashov over-paid for American mills, and when the global steel trade collapsed in 2008, he found himself on the brink of default for billions of dollars in debt. With bailouts from the Kremlin, Mordashov has survived this folly; sold off most of the deadbeat assets; and is now back in front of Putin with his hand out.

This time he wants support for Russian government defence in the hot-rolled steel trade negotiations. He’s also lobbying Washington for defence of his Michigan and Mississippi steelmills against Nucor. Understandably, Mordashov’s double game infuriates Nucor. The practical question for Mordashov is how much of his profit margin is he willing to share with the Kremlin on the one side, the White House (Washington) on the other, to see off this attack.

You would think this is a problem that in striking, potentially, at Severstal’s revenues and at its profit line, it would be something Severstal would report to its shareholders, disclosing what the US Government has done so far; how much steel in trade and how much revenue are at risk; and what Severstal’s position is towards the US claims. But Mordashov, who owns about 83% of Severstal’s shares, sees the problem as his little secret. The company has announced nothing publicly, and is extremely reluctant to answer questions about the US trade investigation.

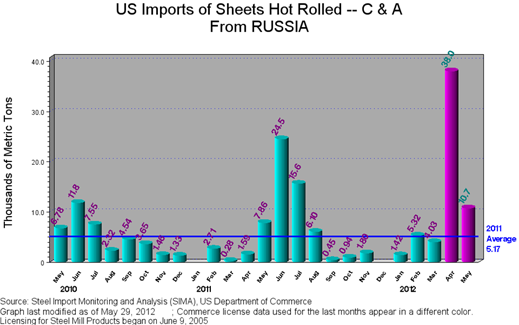

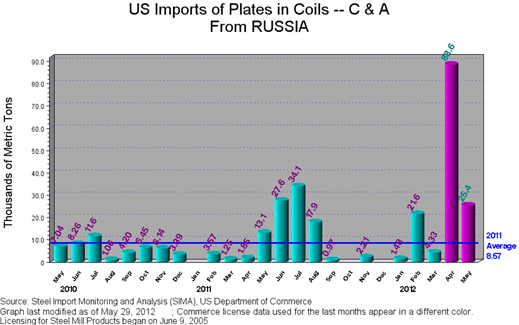

According to ITA publications, this is the problem – a surge of new Russian steel entering the US market this year:

How much of this steel is made and sold by Severstal?

After consulting with his boss, Severstal spokesman Mikhail Ternovykh responds: “Unfortunately, we disclose only the information that is available in the financial and operating reports.” But in those Severstal publishes only aggregates. For 2011, for example, it reports the Russian steel division turned out 4.6 million tonnes of hot-rolled steel and sold it at an average price of $732 per tonne, making total sales revenue of about $3.4 billion. Total sales revenue reported for the past year for this product category across all geographic areas came to $5 billion. According to the financial report for 2011, revenue “by delivery destination” in North America came to $3.9 billion – that is 52% of the group-wide revenue figure. But this appears to include sales of US-made products by Severstal’s US mills, plus exports to the US of products that are not hot-rolled steel.

Another section of the same report indicates that sales by Severstal North America came to $3.4 billion, compared to $10.6 billion from the Russian steel division. There appears to be no way to identify what Severstal exports to the US, and how much it earns on the exports of hot-rolled steel which are now the focus of the US trade investigation.

Nucor is the only complainant to the ITA, according to a 14-page preliminary finding signed on May 23 by Ronald Lorentzen, the deputy assistant secretary for import administration. Nucor’s law firm, Wiley Rein, has been circulating the document ahead of its official publication. ITA officials have confirmed its authenticity.

The document also identifies “interested” US steelmakers – ArcelorMittal, US Steel, Gallatin, Steel Dynamics, and SSAB – as well as the Russian steelmakers, Severstal, Magnitogorsk (MMK), United Metallurgical Company (OMK), Novolipetsk, and Mechel. In practice, the only identified exporter of the hot-rolled steel which is the target of Nucor’s action, comes from Severstal. MMK may be exporting hot-rolled steel to the US; it is answering the US Government’s questions, but it wouldn’t answer questions for this report.

After despatching and collecting questionnaires late last year, the ITA is now reporting that “in their comments, domestic interested parties alleged that offers, and subsequent sales, of Russian hot-rolled steel in the United States are suppressing and undercutting domestic hot-rolled steel prices and, as a result, the Agreement is not fulfilling its statutory requirements.”

What this means is that the reference price benchmark is being set too low by the Department of Commerce, and Russian steel is pouring in over the top. But the reference price is set by the Americans, not by the Russians, and the Lorentzen report from the ITA admits it. “Due to a combination of pricing and cost changes in the hot-rolled steel industry, most dramatically in the rising price of raw material inputs [iron-ore, coking coal, steel scrap] since 2004, the adjustments made quarterly within the reference price mechanism have failed to keep pace with changes in US prices.” Severstal is bound to benefit, because, compared to Nucor, it produces much more low-cost Russian iron-ore, coking coal and scrap, whose sources of supply it owns. So Severstal can sell its hot-rolled product more cheaply than Nucor. So, reports the ITA, “the Department [of Commerce] preliminarily determines that there is price undercutting by Russian hot-rolled steel imports of US hot-rolled steel…”

What happens next on the US side is hostage to the presidential and congressional elections. Nucor wants to apply maximum pressure on the Obama Administration and on Congress to get tough with the Russian steel, and drive it off. But domestic demand for steel in the US market is exceptionally tender at the moment, and sensitive to the price differential imports offer over the local product. So US importers and consumers of steel aren’t in favour of rising steel prices of the magnitudes Nucor would like to book on its balance-sheet.

Nucor’s advocate Price aims to sound as tough as he can without getting into the thorny question of what would happen if the US and Russian trade negotiators agree that the 1999 terms are as obsolete as the current reference prices, and should be replaced from scratch. That would require a new US study of costs of steel production in Russia, domestic sales prices, export sales prices, and margins of profit. Less than four months remain for the two sides to find a solution. Delay may be the optimum one.

Leave a Reply