By John Helmer, Moscow

In the history of the Spanish Main, it was always tricky to tell who had title to what, as the Spaniards stole gold and silver from the Aztecs and the Incas, and the British pirated the Spanish galleons as they made their way across the Caribbean. Who can blame the Danes for not trusting the Russians in what has been announced this week as the biggest delivery of treasure by a foreigner, the A.P. Moller-Maersk group, ever unloaded in Russia’s seagoing business.

Are the terms of the complicated shareholding arrangement a scheme for the Russians to take as much cash for themselves before their container business loses its growth prospects, and profit margins shrink under domestic competition from Vladimir Yakunin (Russian Railways), Ziyavudin Magomedov (Summa Capital), and Vladimir Lisin (Universal Cargo Logistics Holding, UCLH), not to mention Vladimir Putin, Igor Sechin, Arkady Dvorkovich, and Dmitry Medvedev? Is the postponement of shareholding control for the enterprise a hedge by the Danes against the possibility that it will prove impossible to take practical operating control of the assets they are now acquiring as a minority stakeholder?

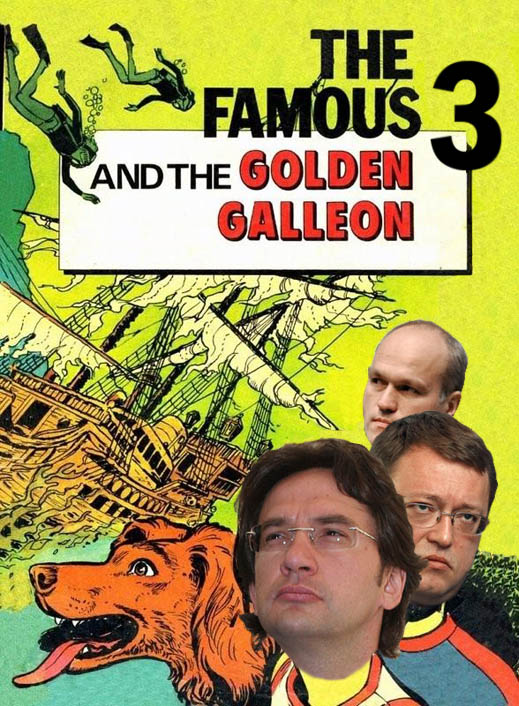

In this week’s deal announcement not even the cash price is clear. According to the press releases by buyer and seller, the three Russian stakeholders in Global Ports Investments (GPI) – Nikita Mishin (image centre), Andrei Filatov (rear right), and Konstantin Nikolaev (middle) — have sold a 37.5% stake in their port terminal operator to APM Terminals B.V., a unit of the A.P.Moller-Maersk group of Denmark. The announcements by GPI and APM say that APM is acquiring half of the shares of Transportation Investments Holdings Ltd (TIHL), a Cyprus entity belonging to Mishin, Filatov, and Nikolaev, along with other unidentified Russians. They have controlled 75% of GPI since it became a publicly listed company on the London Stock Exchange in mid-2011.

In the year since then GPI’s share price has seesawed between $11 and around $17 per share. At the current price of $15 per share, its market capitalization is $2.35 billion. No price for the buy-in by APM and Moller-Maersk has been released, but according to the statement by APM the price paid appears to be 2% below the market price, valuing GPI “at USD 2.3 billion”. By the close of the day’s trading, the share price (GPLR:LI) remained where it was before the announcement was issued.

GPI operates three container port facilities in Russia (including Petrolesport and Moby Dik in St. Petersburg and VSC in Nakhodka), two container terminals in Finland, the largest independent oil products terminal in the Baltic Sea Basin (Vopak E.O.S.) and one inland terminal (Yanino) in the St. Petersburg region. The Russian port terminals account for about 60% of GPI’s revenues ; the Finnish ports, just 5%. The Vopak oil moving business, based at Muuga port in Estonia, provides the remaining revenues, or about 34%.

According to the Russian announcement, “Global Ports will continue to be focused on the high-growth markets of Russia, CIS and the Baltic States and will become the growth platform for APM Terminals and N-Trans in the region.” Kim Fejfer, CEO of APM Terminals, said: “The Russian economy continues to grow and APM Terminals wants to be part of that.”

Just how little the control shareholders of GPI care to reveal about the selling side in this deal was reported when they prepared their initial public offering in London. The release of the prospectus also failed to clarify the all-important link between the purported ownership vehicle of GPI in Cyprus, TIHL, and its owner in the Bahamas, Mirbay International Inc (MII). All that has been revealed publicly so far by Mishin and his associates is that “the ultimate controlling party of the Group is Mirbay International Inc., a company incorporated in Bahamas” – not a word more (Prospectus pages F-82, F-108).

APM almost certainly wanted control for their money — foreign investors understand that playing minority shareholder to Russian oligarchs in their enterprises is an invitation to losing money. The Russian controllers wanted APM to cough up as much cash as possible, but didn’t want to hand over control. The unusually complex structure is the compromise the two sides came up with. One clue — without a control shareholding, APM held back its cash and refused to pay a premium over the trailing market price. Another clue – there is to be no change in the number of board seats assigned to the free-float minority shareholders.

An analysis of the company deal presentations on Monday by Renaissance Capital analyst Alexandra Serova reports that while APM acquires its 37.5% economic interest in the GPI’s holding structure, Maersk and the Russians negotiated their share-voting interest on the board to 30% each, converting some shares into non-voting ones, and allowing the 25% held by the free-float market shareholders to exercise about 40% of the voting rights. The board lineup remains unchanged, with just 2 independents out of 14. According to Serova “if either major shareholder were to sell non-voting shares in the market at the end of the two-year lockup, those shares would receive voting rights; but N-Trans [Russian control group] and APM would each be required to maintain at least a 25% voting stake for five years.”

This looks like the partners have hand-cuffed each other for the foreseeable future, so that they can fight off the pirates together. The risk of competition was spelled out this way in the June 2011 prospectus from GPI: “major shipping lines, such as Maersk, Mediterranean Shipping Company, S.A. (MSC), Evergreen and CMA CGM, operate their own terminals in some countries, and if they were to seek to expand these operations and purchase existing Russian terminals or partner with the Group’s competitors to obtain greater access to Russian terminals, competition may intensify in the Russian container handling market, which could substantially impair the Group’s growth prospects and could have a material adverse effect on the Group’s business, results of operations, financial condition or prospects and the trading price of the GDRs.”

In May of this year, Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) was invited to make the first move by Vladimir Lisin, the steel oligarch and ally of Sechin at United Shipbuilding Corporation, the state-owned shipyard conglomerate. On May 29, it was announced that Lisin’s United Cargo Logistics Holding (UCLH) had sold a 20% stake in one of its assets, SP Container Terminal, to Terminal Investment Limited (TIL), giving the Netherlands-based international its first foothold in Russia’s busiest container port. SP Container is part of UCLH’s stevedoring division and operates the container terminal Lisin owns at St. Petersburg. TIL is Mediterranean Shipping’s partner, with the latter providing the shipping volumes into TIL’s shore terminals. Unlike the Maersk-APM relationship, however, TIL and MSC claim not to be connected by common ownership ties.

The UCLH announcement described its deal as “the first step in a long-term strategic partnership between two companies. Due to the TIL extensive expertise in operation of container terminals all over the world and its strategic relationship with MSC (Mediterranean Shipping Company) the Joint Venture plans to benefit from MCS additional volumes and TIL experience in construction and management of a new container terminal on the territory of the Big Port of St. Petersburg.” UCLH’s existing box facility has annual processing capacity of 500,000 Teus, but as Russia’s import container volume growth has begun to tail off, turnover in 2011, its first full operating year, was just 100,000 Teus. TIL claims to have 20 box terminals worldwide with 17 million Teu capacity. With TIL, UCL says it is planning to build another 700,000 Teus in capacity at St.Petersburg. Port stevedoring is not classified as a strategic activity in Russian law, so no government approval for the Dutch buy-in was be necessary. No price was disclosed, but according to Moscow maritime analyst Alexei Bezborodov, the 20% stake cost TIL and MSC less than $20 million.

Maersk and APM have had to pay up more than forty times the cash. Dmitry Baukov, Lisin’s spokesman at UCLH, says he isn’t about to confirm the terms of their deal with TIL and MSC. “We do not disclose the parameters of the deal. We refrain from opinions and comments on other market participants. We don’t comment on the actions of our partners.” As for whether Maersk has accepted a much higher valuation for GPI than TIL was willing to accept for part of UCLH, Baukov claimed that “in recent years we at the UCL ports group haven’t performed a market valuation of UCLH as a whole or its stevedoring division.”

According to Serova of Rencap, “if at the end of the five-year period N-Trans [TIHL] were to sell out, APM would be the likely buyer of the stake. We believe the deal structure gives APM the comfort of investing in a Russian transport company, while N-Trans obtains a vehicle to sell down the bulk of its economic interest in two years and keep at least a 25% voting interest for a minimum of three years thereafter.”

In the latest port statistics, it is clear that the growth in container transportation in and out of Russia’s ports ground to halt in August, when the container volumes were unchanged from August 2011. The growth rate has been decelerating sharply since the double-digit growth rates recorded in 2011. Countrywide, the Association of Commercial Seaports reports that all-Russia container volumes in the eight months to August 31 were up 8.6% over the same period of last year. This represented more of a slowdown than Russian maritime analysts have been expecting.

At Novorossiysk port on the Black Sea — controlled by Magomedov and the state oil pipeline company Transneft — container volumes for the seven months to July totaled 3 million tonnes, up just 1.8% over a year ago. At St. Petersburg, which ranks second in Russia for container volume after Novorossiysk, container volumes came to 1.4 million tonnes in the January-July period; that represented an annual growth rate of 2.4%. These small numbers are a fraction of the growth rates last year. The one positive thing about them is that they could be much worse, as aggregate cargo volume at St. Petersburg goes negative, dropping now 3% below year-ago levels.

This bad news is more than offset by the future prospects for containers, according to a report just issued by Uralsib bank transportation analyst, Denis Vorchik. “Despite some slowdown in container market growth this year, “Vorchik forecasts, “we expect the long-term upward trend to remain intact, with domestic container throughput growing 200-300% faster than Russia’s GDP. Based on our in-house macro forecast, which implies 3% annual GDP growth for 2011-16E, we assume a 9% CAGR [compound annual growth rate] for Global Ports’ container throughput for this period. The performance of the container division is set to offset declining fuel-oil volumes expected at Global Ports’ VEOS terminal in Estonia.”

A St.Petersburg shipping expert suggests that it is two and half years since President Putin showed a special favour towards Maersk’s shipping business in St. Petersburg. Then it was delivering bananas. “Either this is a lucky coincidence, or it’s a very well prepared deal with Maersk. [The banana line] was not a serious event. But it was the start of a new game.”

Leave a Reply