By John Helmer, Moscow

In the seedier studios of California, when the director cries “We’ve got wood!” he means the male lead has an erection, and it’s his cue to start his business while the cameras roll at a pornographic scene. Russia’s plywood business isn’t as sexy, but it’s faster growing and bigger too. It’s also becoming a oligopoly for Alexei Mordashov, who is already the well-known oligarch of the Russian steel and mining sectors.

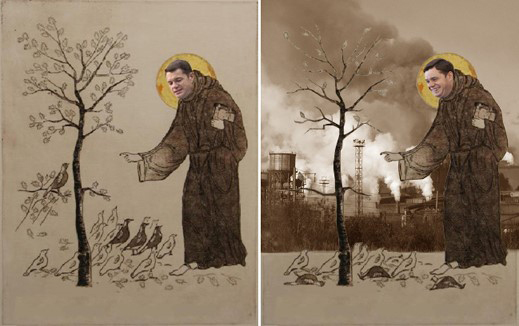

Mordashov (lead image) met President Vladimir Putin in January. He claims he got the president’s go-ahead to build a new wood-processing complex at the village of Suda, outside Cherepovets. Public opposition is fierce – so fierce that the Kremlin is concealing what exactly Putin and Mordashov said about the project at their meeting; how much state money will be given to Mordashov for the scheme; and what Putin intends to do next. Not since Putin took sides with the locals in Irkutsk region against Oleg Deripaska’s paper and pulp plant on the edge of Lake Baikal, has there been such a test of Russians, oligarchs, the President – and who has wood.

The press headline on April 17 was: “Sveza is ready to begin construction of a pulp mill in the Vologda region in 2017”. According to the lead “The Alexei Mordashov project has already received the approval of President Vladimir Putin. Now Sveza, together with the Government of the Vologda region is preparing documents to create a special economic zone in the village of Suda. With this in the Cherepovets area there will not only be an eco-friendly modern plant for the production of cellulose, but also other plants for full processing of wood.”

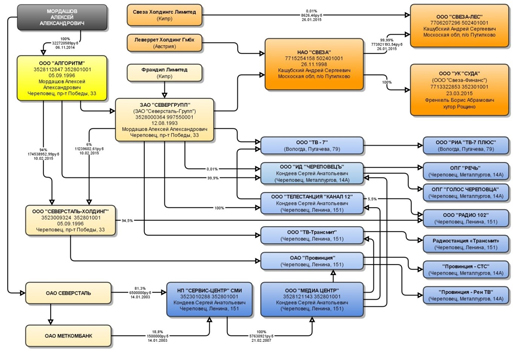

The publication was from Media Centre, a Mordashov outlet. Sveza is the name of Mordashov’s group of timber companies. In Russian, the name sounds like a combination of the Serbian word for union, and the Russian word for a tear from the eye. Mordashov – his name sounds in Russian like “gobface” — owns the Sveza holding company and its units privately and personally through Sveza Holdings Ltd, which is registered in Cyprus. There, according to Bloomberg, nothing at all is disclosed. Expert, the Russian business medium, has reported that the holding is 75.8% owned by Severstal (“Northern Steel”), and 24.2% owned by other Mordashov entities. Mordashov’s stake in the publicly listed Severstal is 79.2%; the free float is 20.8%.

The last Severstal annual report for 2014 reveals that Mordashov is chairman of the board of ZAO Sveza, the Russian subsidiary of the offshore entity. Vladimir Lukin (right), the Severstal chief lawyer and board member, also occupies a seat on the Russian board of Sveza. The Severstal report mentions its subsidiaries but fails to mention Sveza Holdings as one of them. The audited financial report for 2014 identifies 39 Severstal subsidiaries and associates on Severstal’s books. But if you are a shareholder of Severstal and would like to follow what Mordashov is doing with your share of his property, you can’t – he won’t let you.

The last Severstal annual report for 2014 reveals that Mordashov is chairman of the board of ZAO Sveza, the Russian subsidiary of the offshore entity. Vladimir Lukin (right), the Severstal chief lawyer and board member, also occupies a seat on the Russian board of Sveza. The Severstal report mentions its subsidiaries but fails to mention Sveza Holdings as one of them. The audited financial report for 2014 identifies 39 Severstal subsidiaries and associates on Severstal’s books. But if you are a shareholder of Severstal and would like to follow what Mordashov is doing with your share of his property, you can’t – he won’t let you.

Mordashov has made a habit of going to the Kremlin when he wants permission, and also favour, although the details don’t usually become public until later. Mordashov’s request for Putin’s endorsement of his attempted takeover of the European steelmaker Arcelor in May 2006 was a case of hubris and insufficient cash, and can be read here. In the following three years Mordashov went on to find, then lose several billion dollars in buying US steel assets, which he was later forced to sell at a severe loss. Putin’s disapproval of that waste of money and favour isn’t recorded.

This January the Kremlin attempted to keep secret that Mordashov (below) was back asking for more state cash and presidential favour. In the photograph Mordashov’s hands are covering a project memorandum he says Putin has endorsed with a handwritten note saying “consider and support”. How much of an endorsement that actually is remains to be seen.

According to the Kremlin communique, “Severstal Management CEO Alexei Mordashov reported to the President on PAO Severstal’s performance in 2014, the companies’ potential for development on the domestic market and the implementation of social programmes.”

According to what Mordashov said later, the Kremlin was speaking in code. What had happened was that Mordashov told Putin he had a scheme for the biggest investment in Russian history for the timber industry, in order to free Russia from dependence on foreign imports of construction and other wood products. In return he wanted $2 billion. The Russian-language transcript issued by the Kremlin discloses Mordashov telling Putin “the company Sveza, which is a leader in Russia for production of plywood, and produces at six plywood plants, is investing, developing, and considering a project to build a pulp mill in the Russian Federation.” In the transcript Putin’s only response is to refer to steelmaking and to investment in modernization. He ignores Sveza and the mention of a pulp mill, at least on the record.

Industry sources believe the president is familiar with Mordashov’s old tricks, especially the American ones, so off the record he may have asked how much of the Sveza business is offshore. Mordashov may then have offered to bring Sevza onshore if the tax benefit he would be giving up in Cyprus would be offset by the Kremlin. This is how the tax free, er special economic zone around the Sveza plant at Suda surfaced in the off-the-record part of their conversation. But that won’t be enough, according to Mordashov.

“The work is continuing with the Russian government,” Mordashov’s Media Centre claims, “on the creation of the Vologda region special economic zone. The resolution on the project of President Vladimir Putin ‘to consider and support’…does not mean immediate state support. The project has yet to be endorsed. ‘Without state investments in the area infrastructure — quite simply, for the development of railways, highways, interchanges, electricity, etc. — without getting state loan guarantees that will allow us to attract loans at a reduced rate, the economic parameters of the plant are very unprofitable’, says the chairman of the Sveza board of directors, Alexei Mordashov.” For more on the Sveza plan, watch this.

When it comes to measuring the unprofitability of investment, Putin might have told Mordashov, his record in the US has not been matched by any Russian in history. But Putin didn’t.

Nor has the Kremlin yet shown an interest in Mordashov’s record for burying the record of controversially operated plywood production mills, such as Fankom in the neighbouring Sverdlovsk region – the last of the big plywood mills to be taken over by Sveza in 2012. That one appears to have belonged to the notorious Uralmash social and political union.

Just how dominant Mordashov is in the Vologda and Sverdlovsk regions is indicated by this chart of the assets he controls. They include the Severstal steel complex; a bank; television, radio, newspaper and online media; and Sveza, which is coloured orange on the chart.

Source: https://pp.vk.me

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The chart doesn’t go upstream beyond the Sveza entity in Cyprus, and it ignores the offshore trading units for plywood exports to Germany and other destinations. Follow them in this English-language version of Sveza’s history.

The chart doesn’t identify ownership of Sveza’s timber harvesting companies or its processing plants, and since there are no published audited reports, there is no telling how costs, prices and profits are transferred within the group, onshore and off. The Sveza website identifies five processing plants – in St. Petersburg, Kostroma, Perm, Vologda, and Sverdlovsk. Together, they currently turn out about 1.3 million cubic metres of wood board; of that 960,000 cubic metres are plywood, 300,000 cubic metres particle board.

According to other records, another offshore entity called Sungrebe, registered at an address in Tortola, British Virgin Islands, appears associated with Sveza, and may own shares in the Cyprus and Russian entities. Sungrebe appeared after Mordashov bought the Fankom plywood mill in April of 2012. This announcement of the transaction by Sveza omits to say who the selling shareholders were, how much was paid in cash and in shares, if any. Mordashov left a characteristic personal flourish in the text. “This purchase is in line with the group strategy aimed at achieving global leadership in production of wood-based panels.” When Mordashov thought he had Putin’s permission to buy Arcelor and US steelmills, he claimed to be aiming at becoming one of the largest steelmill owners in the world.

Mordashov isn’t the first oligarch-sized Russian to see the prospects in converting state-owned forests into commodity exports cashed offshore. He’s following in footsteps trod already by Roman Abramovich at the Russia Forest Products group; Deripaska’s Continental Management; and the Ilim group belonging to Zakhar Smushkin with Boris and Mikhail Zingarevich (below). The latter defeated Deripaska more than a decade ago, and they have hung on to the Ilim assets.

They have largely stuck to the pulp, paper and cardboard corners of the timber business; RFP is sticking to roundwood and sawnwood.

Mordashov’s business strategy has been to focus on timber concessions he already controls in the Vologda region, and to convert them into a niche in the downstream market for wood panels. Technically, depending on how the materials are combined in manufacture, these can be plywood, particle board, fibre board, or veneer. In trade, they are distinguished from logs or roundwood – the least processed form of timber, and the cheapest to trade – and sawnwood, aka lumber, when the logs have been cut and sized. For more details, read this.

During the Soviet period, state planners had encouraged downstream processing or beneficiation in the timber industry, and supplied the capital required. After 1991 logging went out of control, and downstream wood processing starved for money. Corruption in timber tract leasing, illegal cutting, and smuggling became the business norm. State finance for housing construction stopped. China devoured Russian logs, turning them into plywood and other wood products for re-export.

From 2006, Putin’s government introduced export duties on roundwood with the plan to increase tariffs in order to revive domestic processing. In July 2007, the export duty was raised from the initial €4 per cubic metre to €10 per cubic metre. In April 2008 the duty was hiked to €15. Accompanying these measures were subsidies for investment in wood processing plants and discounted timber leases. It had been planned for the duty to go to €50 on January 1, 2009, but a combination of loss of demand at home, sharp decline in export demand among regular foreign consumers, plus lobbying from Finland, led Moscow to suspend the action.

The 2008-2009 recession hit hard the principal timber production regions: Irkutsk, Vologda, Arkhangelsk, and Krasnoyarsk account for roughly half the output. About 70% of the timber harvest had been reserved for domestic processing, with the remainder exported, mainly to China, Finland and Japan. But in 2008-2009 the domestic cut fell by 20%, while the export proportion fell from 30% to just over 20%. The percentage declines in plywood and paperboard were even steeper. A scheme of export quotas and reduced tariffs was introduced to lift logging.

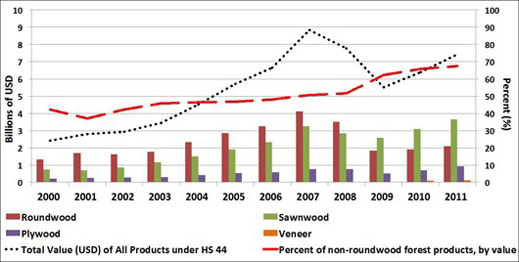

The chart shows what happened to roundwood and plywood volumes, as well as value.

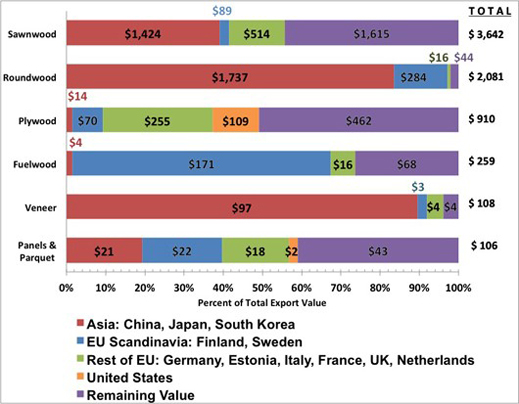

TOTAL EXPORT REVENUE FOR RUSSIAN TIMBER PRODUCTS, 2012

(excluding furniture)

Source: http://www.sras.org

For additional background on the industry players by region, click. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has conducted two recent studies of the Russian industry: the 2012 study is a projection of timber production trends to the year 2030 and can be read here. A follow-up study of the forestry sector in the Russian fareast can be found here.

At peak for Russian timber exports in 2011-2012 the plywood segment of the Russian market represents a trade worth more than $1.4 billion per annum, or about 20% of Russia’s $7.1 billion in total timber export value.

Figure 6: Value of Russian Forest Products Exports in 2011 to Trading Regions by Top Harmonized System (HS) 44 Codes— Percent of Total Value and Millions of USD (Global Trade Atlas, 2012)

Source: http://www.sras.org

The FAO study predicts that if all goes well in the Russian economy, production of plywood between 2010 and 2030 would consume most of the increased volume of timber harvest, and jump by 106%; for particle board, 114%; and for fibre board 155%. Most of that growth, the study anticipated, would fill the demand for domestic construction – and imports would continue to grow.

After Mordashov took over Fankom, he announced Sveza was going to concentrate on plywood and particle board for both the domestic construction industry and export. In July 2013, he claimed he was going to invest Rb6 billion (then $182 million) to build 500,000 cubic metres of new particle board production. That was two years ago, and in the meantime domestic and foreign demand for Russian plywood has been dropping. In February of this year, Sveza revealed it had stopped the project, claiming “the instability of the economy”.

When Mordashov went to Putin days before, he was talking up a change of strategy and a new different line of production – this time Mordashov’s first big venture into pulp and paper.

This is what is now drawing opposition from environmental organizations in Cherepovets city, along with national environmental groups. They have been fighting Mordashov’s pollution record in steelmaking and coalmining for years.

Source: http://johnhelmer.org/?p=6636

This time the opposition appears to be better organized and more influential, while Mordashov’s tactics are proving to be more careless. Supporting Mordashov on the ground are Putin’s representative to the Northwestern Federal District, Vladimir Buliavin (below, left), a career KGB and FSB officer who’s been in this, his first civilian job since 2013; and the Vologda region governor Oleg Kuvshinnikov (right). He’s a native of Cherepovets; he has been on Mordashov’s payroll for years; that is, until he became mayor of Cherepovets, and in 2011 regional governor. Kuvshinnikov is up for election in September.

Opposed to Mordashov’s Suda project are State Duma representatives from the region, as well as members of the Duma Committee on Natural Resources, Environment and Ecology. They may not be strong enough to kill the project on environmental grounds. But if the federal ministries of Economic Development and Finance refuse to agree to Mordashov’s demands for tax relief and budget outlays, the project may be delayed indefinitely.

Cherepovets residents have filed court challenges to the environmental impact studies on which Mordashov and Sveza are relying for their claims that local water supply reservoirs will not be hurt by discharge from the proposed new plant. The residents are also charging that the studies fail to meet the standards required by Russian law and government decrees before the regional and federal authorities may give the go-ahead. The court papers allege that Mordashov and his associates have been fabricating records of public discussions on the scheme; withholding meeting minutes and vote tallies from public inspection, and other manipulation of the record of community consultation.

A citizens’ letter to the Minister of Economic Development, Alexei Ulyukayev (right), was released at the start of this month. “We ask you to intervene in this situation and coordinate [official] action on the [Sveza] application where business interests are placed above the

A citizens’ letter to the Minister of Economic Development, Alexei Ulyukayev (right), was released at the start of this month. “We ask you to intervene in this situation and coordinate [official] action on the [Sveza] application where business interests are placed above the

life and health of citizens of the Russian Federation, but who do not agree to act as a dumb biomass, to listen to the pages of the media about the fact that [the action] should be accepted, because everything has already been decided at the level of the President of Russia, which we do not believe!” Local sources and regional press reports indicate that Ulyukayev’s ministry has rejected the initial application from Sveza, as Ulyukayev appears unwilling to take a position on state tax and budget financing until the legal challenges and the environmental impact issues are resolved.

Sveza declined to answer questions about its plywood and pulp plans.

Leave a Reply