By John Helmer, Moscow

In publishing on Russia, there comes a time when a writer, journalist, bank analyst, television presenter, or academic produces something so lacking in truthfulness, so replete with fawning and meretriciousness, that this website must kill and skin another goat; dry out the vellum; and have a fresh scroll inscribed with the Cat’s Paw – that’s the Personal Abasement Award (PAW).

This award is designed to encourage accountability and ethical reporting on Russia. The PAW committee decided to suspend the Cat’s Paw awards when the start of the Ukraine civil war threatened to overwhelm the supply of vellum and the goat population on which it depends. The goats who have earned the Cat’s PAW scroll have also multiplied exponentially.

At the Financial Times’ Moscow Bureau there has been a tradition of viewing Russian business figures as agents of regime change, making them appear the harbingers of democracy, and pitting them against the Kremlin; that is, once Boris Yeltsin’s destruction of the Russian parliament in 1993, and his election steal in 1996, failed to do the Russian reform trick. For FT reporters this has meant advertorial promotion of the oligarchs applying to the City of London to raise debt and equity finance; buying London and country real estate; promoting themselves with British public relations and deterring investigation of their business with British libel law firms.

The FT reporters have been closely pressed by rivals at The Times, the New York Times, the Guardian, and other print and broadcast media. The promotion of Alisher Usmanov by Mark Franchetti of the Sunday Times in 2007 came two years too early to qualify for the Cat’s PAW. Michael Wines (right) of the New York Times qualified eight years early, when he won The Exile’s award for being the Worst Western Journalist in Moscow for 2001. The award that year was a horse-sperm pie. The Exile was a stickler for the facts – the horse was named Sobornik.

The FT reporters have been closely pressed by rivals at The Times, the New York Times, the Guardian, and other print and broadcast media. The promotion of Alisher Usmanov by Mark Franchetti of the Sunday Times in 2007 came two years too early to qualify for the Cat’s PAW. Michael Wines (right) of the New York Times qualified eight years early, when he won The Exile’s award for being the Worst Western Journalist in Moscow for 2001. The award that year was a horse-sperm pie. The Exile was a stickler for the facts – the horse was named Sobornik.

The first Financial Times reporter to win the Cat’s PAW, Ben Fenton in 2009, did it with an advertorial for Alexander Lebedev, the control shareholder of National Reserve Bank and proprietor of the Evening Standard and Independent newspapers in London. Fenton’s report managed to avoid a single source of evidence on Lebedev’s bank, his debts, or his business conduct. An investigation of that can be read here.

When invited to defend his professional method and veracity, Fenton refused. He subsequently stopped being an FT reporter and joined Edelman, which bills itself as the world’s largest public relations company. There Fenton runs what he calls the “creative industries practice”. Whether that includes fiction Fenton doesn’t make clearer today than he did when he practiced on Lebedev at the FT.

In Moscow FT reporters have regularly promoted favourites – Chrystia Freeeland was enamoured of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Mikhail Fridman; Catherine Belton of Oleg Deripaska and Suleiman Kerimov. For recognition of these reporters, the PAW committee judged there was never enough vellum to roll into citations to match the lack of truthfulness. Belton finally won an award in 2012. Since the end of 2012 she has been on what she calls “an extended sabbatical”.

This week the PAW committee was recalled to consider an FT report by Courtney Weaver (below, left) and Jack Farchy (right). They make it appear that the collapse into insolvency of Mechel, the steel and coalmine group owned by Igor Zyuzin (lead image, right), is the outcome of Zyuzin’s brave resistance to President Vladimir Putin and the Russian state banks; and that the only option for Mechel’s rescue is to keep the managerially irreplaceable Zyuzin in executive control — with all 67% of his stake in the company intact.

Weaver, an American, is deputy chief of the FT’s Moscow Bureau. She tweeted an advertisement for her story as “our in-depth look with @jfarchy into Russian tycoon Igor Zyuzin & his indebted mining empire”. She followed that with a promo from Oliver Bullough calling it “a fantastic piece”. Bullough reported for Reuters from Moscow between 2002 and 2006; he is currently employed by this collection of NATO governments, plus the Legatum Institute.

Tagged for what the FT calls its “Big Read”, here is the story by Weaver and Farchy.

The reporters claim Zyuzin himself refused to be interviewed, but gave permission for others to speak for him. The only sources named in the story are employees of Zyuzin. “Moscow bankers may have few kind words for Igor Zyuzin,” Weaver and Farchy report, “but in this drab industrial town in the Urals [Chelyabinsk] the Russian billionaire has the status of a minor deity.” For substantiation, they quote “starry-eyed” workers including the head of rolling-mill no. 3 at Mechel’s Chelyabinsk complex, and the plant’s chief engineer. They, and the chief executive of the group, Oleg Korzhov, are the three named sources for the picture of Zyuzin’s “stubborn refusal” to allow the bullying state banks and the threatening Putin to prevent his “focus on maintaining production growth and keeping his 70,000 employees happy”.

Chris Weafer, a Moscow analyst, is quoted as saying nothing concrete about the happiness of Mechel’s employees or minority shareholders. “It has been decided by the Kremlin that the most important thing is stability in the system,” Weafer is cited as revealing.

As for the intrepid reporters’ anonymous sources, they are identified as “a former top manager at Mechel”, “one person close to Mechel”, “a former Mechel executive”, and “one ex-Mechel executive” – that sounds like four sources, but they may be one. There are also “one senior state banker”, “one senior Russian banker”, and “one state banker”; this trio too may be one and the same person.

The three state banks to which Mechel owes the bulk of its current $7 billion in debt – Sberbank, VTB, and Gazprombank – are not recorded as having been contacted or asked for comment. Neither are Mechel’s commercial bank lenders – Alfa, Credit Bank of Moscow, Unicredit, Raffeisen, ING, BNP Paribas, HSBC, Nordea, Société Générale, Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse, Royal Bank of Scotland and Natixis. Over the past three years, these banks have held between 20% and 40% of Mechel’s debt.

If they were the lucky ones to be repaid, and the three state banks obliged Zyuzin by lending him the money to pay the others off, Weaver and Farchy appear not to have investigated what Zyuzin agreed in exchange. How much of Zyuzin’s shareholding has been pledged to secure the state bank loans is unclear, but it is reportedly a larger proportion of Mechel’s shares than its 33% free float. So in the refinancing of its foreign bank debt, the takeover of the bankrupt Estar steelmills, the privatization of Vanino port, the guaranteed bonds for Mechel’s coal projects in Sakha, and the proposed sale of Mechel Mining, there has been a de facto nationalization of the revenue and debt lines on Mechel’s balance-sheet, with Zyuzin left in charge of management. This has been obvious to everyone for several years.

Zyuzin has been able to keep this secret from the stock market because Mechel claims the “foreign private issuer” exemption from disclosure, under Rule 405 of the US Securities Act. That means he doesn’t report what all domestic companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange are required to report. Regulators at the US Securities & Exchange Commission are obliged to let him off the compliance hook. The FT’s reporters this week have proved to be good at keeping Zyuzin’s secret by not asking him, or anyone else who knows.

But the biggest secret Weaver and Farchy have kept is the one about Putin. Their report recalls that “everything was on track” for Mechel’s prosperity, “until [Zyuzin] missed an appointment, due to illness, with Mr Putin on July 26 2008, just as commodity prices began to slide.” If not for Putin’s diktat then and since, the FT journalists imply, Zyuzin might have been able to realize his old-fashioned vision for making Mechel happy. An alternative, without Zyuzin enriching himself at Mechel’s expense, might have occurred to Putin in 2008, but it hasn’t occurred to the FT investigators now.

Weaver and Farchy weren’t told by their Mechel handlers, nor did they find out on their own, that on July 23, 2010, Putin visited Chelyabinsk (right); inaugurated a new casting machine at the Mechel plant; and gave Zyuzin a public apology and endorsement. “I can only regret,” Putin said of his remarks in July 2008, “that this caused the company’s capitalisation to fall by 20%, if I am not mistaken. Anyway, Mr Zyuzin, I want to thank you for everything you did and your continued respect for domestic consumers and Russian law.”

Weaver and Farchy weren’t told by their Mechel handlers, nor did they find out on their own, that on July 23, 2010, Putin visited Chelyabinsk (right); inaugurated a new casting machine at the Mechel plant; and gave Zyuzin a public apology and endorsement. “I can only regret,” Putin said of his remarks in July 2008, “that this caused the company’s capitalisation to fall by 20%, if I am not mistaken. Anyway, Mr Zyuzin, I want to thank you for everything you did and your continued respect for domestic consumers and Russian law.”

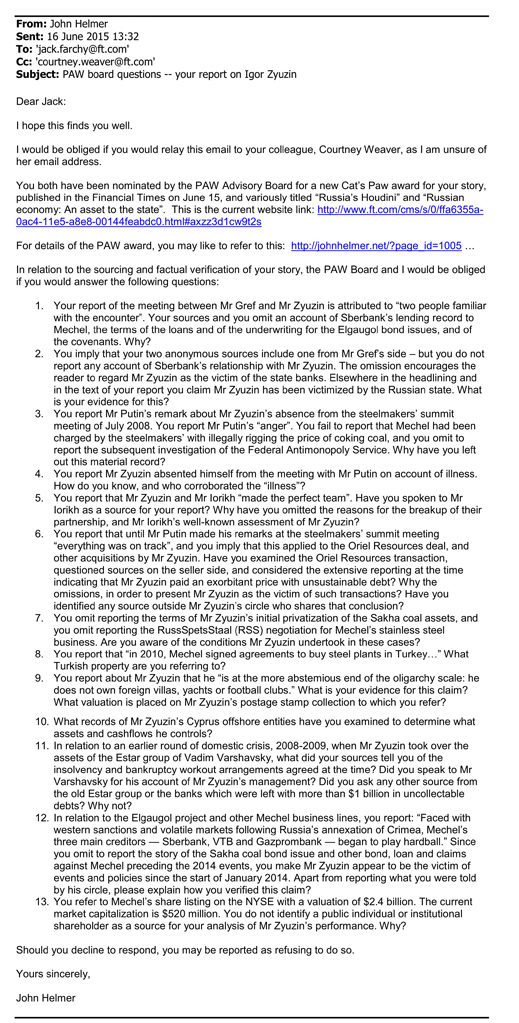

The chart of Mechel’s share price shows that in the following six months Putin might be credited for the 52% jump in value, and the peak valuation achieved on February 4, 2011. At that point Mechel was worth $14 billion; and Zyuzin was $3 billion better off personally than he had been when he ducked meeting the president the previous July. The FT reporters omit to record how grateful he was to Putin. The chart shows that Mechel’s decline started in February 2011 and has headed steadily down towards worthlessness before the Ukraine conflict commenced in 2014.

FIVE-YEAR TRAJECTORY OF THE MECHEL SHARE PRICE, 2010-2015

Source: http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/MTL:US

As for Zyuzin’s respect for Russian law, the reporters have ignored the voluminous litigation records the state banks have filed in the Russian arbitration court system, explaining what Zyuzin and his pocket companies and offshore cutouts have done over the past eighteen months. Also ignored by the FT are the records in US state and federal courts alleging Zyuzin’s self-serving mismanagement and violation of shareholder pledges.

To clarify what Weaver and Farchy might have up their sleeve by way of better evidence than they included in their publication, and to give them the opportunity to defend their story line, they were invited to respond to these questions:

Farchy, a commodities and natural resources specialist , who is also assigned to cover the Central Asian states, was obliged to travel out of Moscow after Monday’s story appeared. Weaver confirmed that both of them had received the email from the PAW committee.

In a telephone interview, Weaver said there will be no response. “There are too many questions, and not enough time to respond”, she said. Asked whether she had made a mistake reporting Mechel as having bought a Turkish steel plant, she refused to say. Asked whether she should provide evidence for reporting Zyuzin and his business to have been victimized by the Kremlin, Weaver replied: “I don’t think that’s what the story said.” Asked whether she had a duty as a reporter to be accountable for what she reports, she cut the telephone line.

A few minutes later, she emailed to say: “all our press requests are handled by the FT’s PR department. Please feel free to pass on your questions to them. Their email is press@ft.com. We stand by our story.”

At Mechel, spokesman Alexei Ryzhkov denied that Mechel had ever acquired a Turkish asset. “This is a mistake of the FT journalists.”

Leave a Reply