By John Helmer, Moscow

Last year the government of Botswana decided to halt a 2-year old, multimillion dollar contract for its state mining company to purchase a nickel mine from Norilsk Nickel, Russia’s largest mining company. The government also decided to put its state nickel mining company into bankruptcy to protect against court claims from Norilsk Nickel. At the same time, the Botswanans tried arranging a buyout of their mining company by a penniless investment group in the United Arab Emirates.

A document, drafted on March 13 and circulating since then among Botswana Government officials, reveals details of the buyout and confirms that the Norilsk Nickel deal was negotiated in bad faith by the Botswanans without the money to pay for it. The Botswanan Government then sought secret help from the South African Government to block the deal.

This sequence of events, decided behind closed doors, have so far cost Norilsk Nickel a contract worth $277.2 million, and the conviction that the Botswana Government cannot be trusted to honour either its obligations to foreign investors, or its promises of employment and prosperity to its own people. Mining sources in Gaborone, the Botswana capital, say it’s a case of politicians inexperienced in business “doing something either so clumsily they are culpably incompetent, or so cleverly they are corrupt. Either way the Norilsk Nickel case is a tragedy for the country.”

The deal was the last exit from Africa by the Russian company, convinced that Botswana is a much higher risk than has been admitted until now in reports of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and Transparency International. As for the smoking-gun letter, Sadique Kebonang, the Botswana mining minister to whom it was addressed, says: “I am unaware of it. I will look for it since you have brought it to my attention.” He declined “to respond to matters that are before court and are subject to the sub judice rule.”

A source in Gaborone who is aware of the letter says it was dated March 13, 2017, and runs for six pages. The author, according to the source, was Paul Smith, head of the state holding company for Botswana’s mining and mineral assets. A month after Smith wrote the letter to Kebonang, Kebonang dismissed him.

The document, reported for the first time this week, appears to be unknown to lawyers acting for Norilsk Nickel. Last Thursday the company’s African subsidiary filed advance notice of a lawsuit against the Attorney-General, the Minister of Finance, and the mining minister in the Botswana High Court. The notice charges the government with reckless business conduct and deceit. In a statement released to the press on Friday the company said it plans to ask the Botswana Government to pay $277.2 million in compensation plus legal costs.

Smith, a South African national and veteran executive in the African mining industry, has been the first chief executive of the state holding, Minerals Development Company Botswana (MDCB). This was created in August 2015, as the Botswana parliament was told, “to help government manage all its assets in the mines such as those in Debswana [diamond mines], BCL [nickel, copper] and others [coal].” BCL stands for Bamangwato Concessions Ltd; in 1977 the name was changed to BCL.

Smith was head-hunted to run MDCB, reportedly by President Ian Khama, and started work in February 2016. In the government he reported to Khama’s mining minister, Kitso Mokaila. Khama, a former general commanding the Botswana Defence Force, was Vice President from 1998 to 2008, and President since then. He retires next year; the political contest to succeed him is a fierce one.

Left to right: MCDB chief executive Paul Smith; former Mining Minister Kitso Mokaila; President Ian Khama.

At the time Smith started at MDCB, the strategy of Khama and Mokaila was for BCL to complete a two-year old deal to buy a low-cost source of nickel ore to replace Botswana’s own mines whose costs were rising as the mines went deeper and the nickel grades dwindled. The higher grade, lower cost substitute came from the Nkomati nickel mine in South Africa; it is located at Mpumalanga, 650 kilometres to the south. Nkomati was essential to the Botswana government’s plan to keep its nickel mining and processing businesses going, on condition the lower cost of production reduced the government subsidy for BCL.

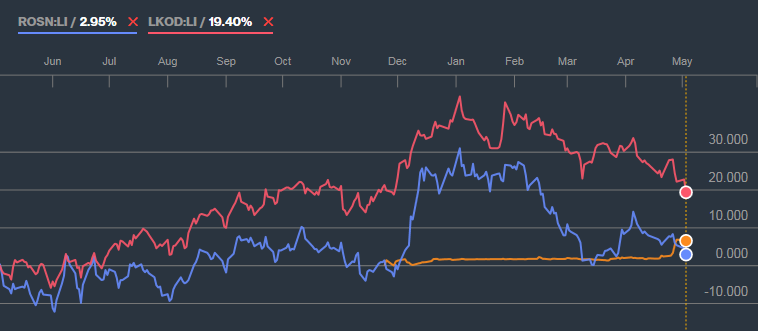

The Nkomati source had been owned by Norilsk Nickel in a 50/50 joint venture with African Rainbow Minerals (ARM), a leading South African mining house. Norilsk Nickel had bought its stake, along with the Tati nickel mine in Botswana, when it took over LionOre Mining in May 2007. For that story, read this.

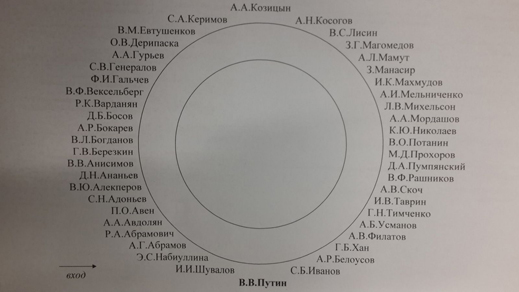

In 2013 Vladimir Potanin, the control shareholder of Norilsk Nickel, decided with the other shareholders of the Russian company to sell off their non-Russian assets and concentrate on mining and refining in Russia. In October 2014 it was formally agreed that Norilsk Nickel would sell to BCL the Tati mine, plus the much more valuable half-share of the Nkomati mine.

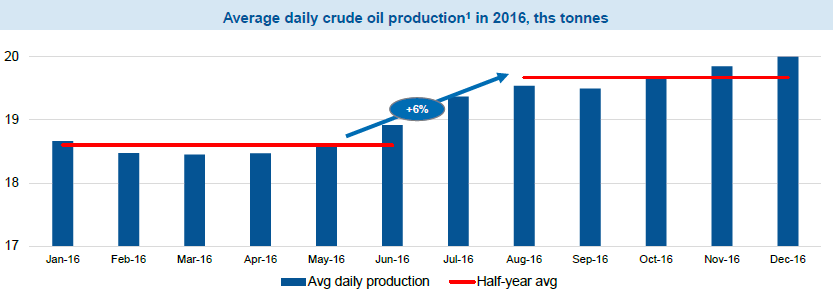

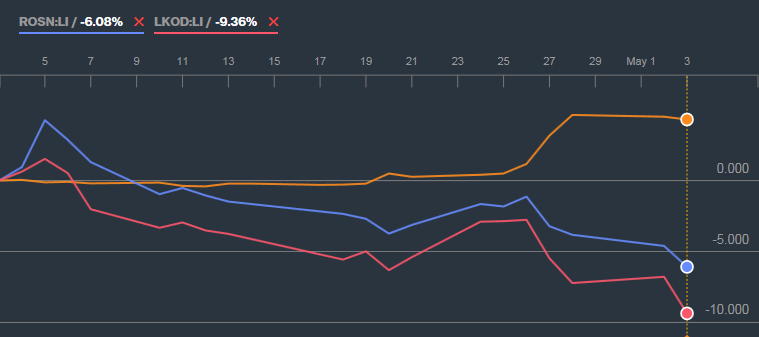

The original price of the deal was $337 million. But in the market at the time the nickel price ranged between $7 and $9 per pound ($15,800-$19,400 per metric tonne). What happened next was that the nickel price collapsed to a low in February 2016 of $3.76 per pound ($8,299 per tonne). Norilsk Nickel had timed its exit well, but from the Botswanan point of view, the contract price was too high. After negotiations the Russians agreed to a deferred payment scheme and reduction of the price.

The Botswanan government asked Barclays Africa Bank to come up with a scheme for financing the deal. Barclays proposed to issue bonds for at least $200 million. That was on top of a 1 billion pula loan (Botswana currency equivalent to $96 million) already disbursed to BCL and guaranteed for repayment by the government. The bank made no judgement on the viability of the nickel mining project or BCL’s solvency. Instead, it asked the government to double its guarantee and cover the risk that the price of nickel would remain low and BCL fail to generate the means to repay the bank.

Source: http://www.kitcometals.com/charts/nickel_historical_large.html#5years

Smith’s running orders were to consolidate into MDCB the country’s diamond, coal, nickel, copper and other mining, processing and trading assets. For the survival of the nickel sector he was to finalize the takeover of Nkomati from Norilsk Nickel for a lower price. A Botswanan financial expert says the end of the commodity price boom has left the government confused. “We don’t know what to do when the resource rentals on which the country has depended for so much and for so long run out. The politicians have been taking decisions short-sightedly.”

In Moscow until now, Norilsk Nickel has been reluctant to discuss the conflict with Botswana government officials. The Russian Embassy in Gaborone and the Kremlin have not yet been involved. “Norilsk Nickel has tried on numerous occasions, and through numerous channels, to reach a satisfactory and amicable resolution”, the company said last Friday, “but none has been forthcoming. Norilsk Nickel has therefore been left with no other option but to pursue a resolution through legal channels. … the business of BCL has been carried on recklessly and the Government was party to that recklessness through the actions of individual Government Ministers, MDCB and the Government-appointed directors on BCL’s board.”

Botswana business sources say the president’s appointment of a new mining minister late last year ruled out negotiating a compromise with the Russians. On October 5 Khama replaced Mokaila as mining minister with Kebonang. The cabinet has yet to post this change on the internet. Two days after Kebonang’s appointment, Friday October 7, Khama called a cabinet meeting in which Kebonang tabled the cancellation of the Norilsk Nickel deal.

The ministers discussed their concerns for the risk of accidents at BCL’s cash-starved mine operations, and for the government’s growing liability for BCL’s financial troubles. “There was legal advice; there was accounting advice; everyone agreed BCL could not continue,” claims a participant. The cabinet record reveals Kebonang told the ministers it was necessary to put BCL into bankruptcy as soon as possible in order to protect BCL, MDCB and the government from a lawsuit from Norilsk Nickel challenging the abrupt cancellation of the contract. Khama and Kebonang agreed with the rest of the cabinet on Friday evening. The next day all mine operations were ordered to halt.

On Sunday, October 9, 2016, BCL was in front of High Court Justice Gaolapelwe Ketlogetswe requesting an immediate order to liquidate BCL, and authority to appoint a provisional liquidator to take over the company. Botswanan officials differ in their versions of what was intended. A source close to the government says the cabinet “was short-sighted. They must have known the risk they were running, not just with the Russians, but for the government in the international capital markets.” Another source says the mine closure “had to be done quickly. It was not aimed at Norilsk Nickel. The damage to the Russians was collateral damage. An unfortunate outcome.”

Kebonang followed up by telling Smith his job was to agree with a new buyer Kebonang planned to introduce for the BCL assets. Kebonang’s buyer was an entity called Emirates Investment House (EIH), based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and headed by Abdulla Mangoosh. He had been floating deal proposals in Gaborone for several years without result. Then in February 2017 Kebonang flew to meet Mangoosh in the UAE. Without other Botswana officials present, Kebonang signed a memorandum of understanding on behalf of the Botswana Government.

Left to right: new Mining Minister Sadique Kebonang; Justice Gaolapelwe Ketlogetswe; Abdulla Mangoosh of EIH.

The MoU between Mangoosh and Kebonang – revealed now for the first time — promised that EIH could buy BCL for one dollar while the Botswana Government would pay BCL’s multi-million dollar liabilities. Also in the memorandum EIH reserved the right not to restart the mine if it decided there was insufficient profitability, while it could exercise the option to sell BCL’s assets to others. Six months after the court hearing put a stop to the Russian deal, and two months after the MoU, Smith was fired by Kebonang for his opposition to the terms the government had agreed for the Mangoosh-EIH deal.

Smith’s letter of March 13 followed MDCB’s negotiation with Mangoosh and a Swiss named Karl Georg Neubacher. Neubacher who runs a company called SES with offices in Botswana and UAE, has reportedly been an active go-between in the Botswanan government’s deal-making.

The Smith letter disagreed with the concessions Kebonang had agreed to in the MoU. The letter warned that lack of cash made operating the BCL mine shafts unsafe, and miners’ lives would be at risk unless EIH guaranteed details of a spending plan to ensure that once production resumed, EIH would guarantee investment in mine safety, ecological protection, and production targets. Without EIH’s agreement on those points, there was apprehension at MDCB that EIH’s scheme was intended to take the assets at no cost and speculate on flipping them to another buyer, without protecting the miners or the government in case the mine walls or the price of nickel collapsed.

A Johannesburg mine entrepreneur who has done business with Smith in the past comments: “Paul is a straight-shooter. On the technical level he will know and he will tell you what is real, and what isn’t. This can be unwelcome advice in some circumstances.”

The sacking of Smith came as much of a surprise as the collapse of the Norilsk Nickel sale and the bankruptcy of BCL had been earlier. Smith was fired on April 17; that was Easter Monday – a public holiday in Botswana, when Kebonang’s ministry and Smith’s office at MDCB were closed.

Officials in Gaborone say Smith had been engaged by Khama to put all of Botswana’s mining and mineral assets into a single company, and reorganize them so they would relieve the government of the high cost of subsidizing the loss-making mines. The officials agreed with Smith that BCL had little prospect of mining and processing nickel without continued loss-making. The cabinet meeting on October 7 had been unanimous in accepting Smith’s advice, including Khama and Kebonang. Later, when Kebonang told Smith to accept a scheme for bankrupting BCL, wiping out its liabilities by paying a fraction of its debts; ignoring Norilsk Nickel’s contract of sale; and then selling the company to Mangoosh, Smith flatly refused.

Kebonang, contacted on Friday at the Ministry of Mineral Resources, Green Technology and Energy Security, refuses to respond to a request for details. Earlier Kebonang had leaked his version of the sacking by attacking Smith personally, and by making the Mangoosh company appear to be a better investment partner for BCL than the Norilsk Nickel deal. Kebonang’s story appeared on the morning after the Easter holiday in the Botswana Guardian. It was published anonymously, without a byline.

“Smith’s relationship with almost all the stakeholders [of MCDB] and his principals is said to have been wanting. This led to many of them complaining… Kebonang confirmed to BG [Botswana Guardian] News that he has fired Smith. ‘The MDCB board had a meeting on Monday and made a recommendation that Smith must be fired which I have acceded to’.”

Attempts to contact Mangoosh and verify the business record of EIH, have proved fruitless. Leaks to the Botswana press describe Mangoosh as a millionaire who manages billion-dollar investments for the ruling al-Nahyan family of Abu Dhabi. The EIH website reports no physical office address and its email contact channel does not work. No trace of the website’s reported business investments can be found.

Mangoosh, who says he received a degree from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, announced in March that he was sponsoring “Botswana Week” in Abu Dhabi this month, but that did not materialize. Mangoosh also told a Gaborone newspaper that his purchase of BCL is a certainty. “Due diligence is necessary to meet EIH internal requirements, but is just confirmatory; EIH will proceed with the investment,” he promised at the same time as he announced Botswana Week.

In Gaborone a source has heard Mangoosh tell Botswanan officials he has his own channel to President Vladimir Putin.

Botswana’s Ambassador to Russia, Lameck Nthekela, presents his credentials to President Putin, with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in the background, January 16, 2014. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20070/photos/18457

A financial analyst in Dubai says: “We understand that EIH has attempted, and failed, to make several investments in Africa, including Mali, Tanzania and some other West African countries. Based on an analysis of funds available to EIH, there is little to suggest that they could participate in the acquisition of BCL, much less run it.”

A City of London source who does due diligence on business proposals from the UAE comments: “Mangoosh may be real, but he is insignificant. He is not fronting for any [Emirati] royal we know.”

The liquidator whom Kebonang arranged to take control of BCL has also expressed public skepticism that the Mangoosh bid was financially credible. Appointed by the High Court, and reporting to the Court Master, the liquidator is Nigel Dixon-Warren (right), a senior partner of the KPMG accounting firm in Gaborone and a Botswanan national. Dixon-Warren has been in charge of BCL; Smith in charge of MCDB; Kebonang in charge of the sale of BCL to Mangoosh. At Kebonang’s insistence, Dixon-Warren has twice applied for extension of time from the court before the required hearing to decide whether the provisional liquidation should become final. Only after that happens can the formal process start for registering BCL’s creditors and its obligations. Sources in Gaborone claim KPMG conducted a due diligence on Mangoosh and EIH, and reported back to Dixon-Warren, who informed the Court Master. The KPMG report is known to several government officials.

skepticism that the Mangoosh bid was financially credible. Appointed by the High Court, and reporting to the Court Master, the liquidator is Nigel Dixon-Warren (right), a senior partner of the KPMG accounting firm in Gaborone and a Botswanan national. Dixon-Warren has been in charge of BCL; Smith in charge of MCDB; Kebonang in charge of the sale of BCL to Mangoosh. At Kebonang’s insistence, Dixon-Warren has twice applied for extension of time from the court before the required hearing to decide whether the provisional liquidation should become final. Only after that happens can the formal process start for registering BCL’s creditors and its obligations. Sources in Gaborone claim KPMG conducted a due diligence on Mangoosh and EIH, and reported back to Dixon-Warren, who informed the Court Master. The KPMG report is known to several government officials.

The Gaborone court has scheduled May 15 for the final hearing on the liquidation. That’s also the deadline Kebonang agreed with Khama and the cabinet for Mangoosh and EIH to sign the deal they have promised. In the meantime EIH has refused to provide the government or BCL with a $10 million break-fee commitment. That was requested from Mangoosh by Dixon-Warren to ensure that for Kebonang’s favours so far, including exclusive bidding rights to the BCL assets and the extension of time from the court, the creditors of BCL would not be disadvantaged if Mangoosh fails to make good on his promise. Mangoosh turned Dixon-Warren down.

Mangoosh reportedly met Smith at MDCB in March. Sources believe they agreed in principle on restarting nickel production at BCL. When EIH was asked to provide MDCB with its guarantee of mine reopening, with a schedule of fresh production targets, Mangoosh refused. The evidence of the liquidator’s break-fee condition, the Kebonang MoU, followed by the rejection of Smith’s terms, convinced Botswana Government officials – reportedly including Finance Minister Kenneth Matambo — that the Kebonang-Mangoosh scheme would be lucrative to its promoters but hazardous for the mine workers and for the government’s legal liability.

Mining sources claim Mangoosh has hired WorleyParsons, an Australian mine consultancy, to study the prospects of the Botswana nickel mine and processing operations. Financial advisors have also been engaged to value the assets, and propose a financing scheme for BCL’s nickel business. Time is running out, though. Less than two weeks remain before the make-or-break bankruptcy hearing. If there is no buy-out, the liquidation process will start, and BCL’s assets will be sold by open, competitive bidding.

In the meantime, Norilsk Nickel has commenced legal proceedings in the Botswana High Court in Gaborone, challenging the legality of Kebonang’s moves and Dixon-Warren’s liquidation. This started on December 12. The judge for that case, Justice Lakvinder Walia, announced on April 7 that he is retiring.

Norilsk Nickel has also opened a case against BCL and the Botswanan Government in the London Court for International Arbitration (LCIA), charging breach of the contract of sale. The Botswanans through Dixon-Warren have responded by suing in the South African High Court to reverse the South African mining ministry’s approval of the Nkomati sale to BCL. The London litigation has been suspended while the judges in Gaborone and Pretoria decide the claims before them. Representing Norilsk Nickel in these courts is Michael Marriott (right), chief executive of Norilsk Nickel Africa. Marriott is a South African with a past career at mining houses Anglo American and Cluff Mining.

London Court for International Arbitration (LCIA), charging breach of the contract of sale. The Botswanans through Dixon-Warren have responded by suing in the South African High Court to reverse the South African mining ministry’s approval of the Nkomati sale to BCL. The London litigation has been suspended while the judges in Gaborone and Pretoria decide the claims before them. Representing Norilsk Nickel in these courts is Michael Marriott (right), chief executive of Norilsk Nickel Africa. Marriott is a South African with a past career at mining houses Anglo American and Cluff Mining.

In last week’s notice Norilsk Nickel Africa accused the Botswana Government of providing official assurances the transaction contract would be implemented, although in fact officials did not intend this to happen. A source in Pretoria adds that Botswanan officials secretly asked their South African (SA) Government counterparts to help by delaying the approval they were required to give because Nkomati is a South African mine.

Sources close to the court proceedings say the papers reveal that after months of stalling, the SA Department of Mineral Resources gave its approval for the BCL purchase to go through in August of 2016. On August 30 Norilsk Nickel warned the Botswanans their contract required them to implement the transaction without further delay. An extension of time to pay up was offered to October 12. That was the deadline which triggered Khama and Kebonang into action over the weekend of October 7-9; putting BCL into bankruptcy; and then on October 11 appointing Dixon-Warren as liquidator.

Contacted for his comment on what is happening, Dixon-Warren denies acting prejudicially. He confirms what he has been already reported as telling the courts and the Botswana press – there will be no further extension of time for the EIH sale bid after next week; and the Botswana Government has agreed to pay for the care and maintenance of BCL’s operations until the EIH bid is decided one way or another.

Through Dixon-Warren the Botswanan Government is now challenging the SA mining minister, Mosebenzi Zwane (below, left) , and the SA ministry’s director-general, David Msiza (right), for approving the Norilsk Nickel sale of the Nkomati mine stake to BCL — unlawfully Botswana alleges.

The Botswanans now claim the South Africans lacked the evidence that BCL had the financial capability to pay for the Nkomati mine stake, and for continued business operations. The allegation is scheduled to be heard in the SA court in a month’s time. Lawyers in Pretoria point out this is a boomerang – the evidence of BCL’s insolvency which the Botswanan Government claims the SA Government should have known must have been known beforehand to the Botswanans themselves.

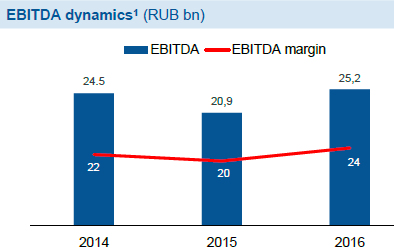

Norilsk Nickel’s position is that the financial resources to complete the deal for BCL had been repeatedly assured by the Botswana Government. Just how profitable the Nkomati mine can be depends on the price of nickel in the global market. The latest financial report from African Rainbow Minerals (ARM), which owns the other 50% of Nkomati, indicates that the mine turned its 2015 losses into profits last year. This year, ARM reports that the cash cost of mining nickel at Nkomati has been cut by 20%.

The Nkomati open-pit nickel mine

According to papers issued by ARM, and its predecessor Anglovaal (Avmin), in 2004 a 50% stake in Nkomati was valued at $150 million. The nickel price then shot up, only to fall again. After several impairments were announced, ARM reportedly values its stake at $130 million. The company was asked to confirm this figure today. It did not reply.

Officially, Norilsk Nickel says that in negotiating its transactions with BCL, including the sale of Nkomati, the Botswana Government played a central role; President Khama himself had issued a directive expressly approving the terms of the deal in 2014. A year later, then Mining Minister Mokaila issued a letter to Norilsk Nickel promising “Government will support all processes required to sustain the business”, and also that “Government will not permit BCL to enter into liquidation (whether voluntary or compulsory)” during 2016.

Anti-Russian sentiment has been fanned among the Botswanans to ward off local allegations that BCL executives and board directors had caused losses by their own mismanagement and corruption. One of the allegations is that the cabinet had only gone to court to prevent the Russians filing to bankrupt BCL first. “The way we have done it,” BCL chairman Khaulani Fichani (right) has told the press, “ is to give that power [to arrange the Nkomati deal] to the provisional liquidator and look at the options of revising the business. We would not have that option if the creditor [Norilsk Nickel] was in control. If a creditor comes and forces you into provisional liquidation, they have the powers to supervise the process.”

local allegations that BCL executives and board directors had caused losses by their own mismanagement and corruption. One of the allegations is that the cabinet had only gone to court to prevent the Russians filing to bankrupt BCL first. “The way we have done it,” BCL chairman Khaulani Fichani (right) has told the press, “ is to give that power [to arrange the Nkomati deal] to the provisional liquidator and look at the options of revising the business. We would not have that option if the creditor [Norilsk Nickel] was in control. If a creditor comes and forces you into provisional liquidation, they have the powers to supervise the process.”

Fichani has also blamed the collapse of the price of nickel for BCL’s bankruptcy. “Obviously there are things that we could have done better…At the core of things is: if you sell a product at $4 while your operational cost was $8, can you make a profit?”

Norilsk Nickel’s financial reports and market presentations indicate it has accepted that loss-making at its Botswana and South African assets led to the decision to sell out in 2013; and that the fall in the price of nickel reinforced that decision. Norilsk Nickel is now telling the High Court in Gaborone that it had relied on the Botswanans for “fair, frank and reasonable dealing”. But because Botswanan government officials had acted recklessly and in secret, Norilsk Nickel adds, the government is now liable for all the contract liabilities, plus legal costs.

On the Gaborone grapevine the innuendo of corruption surrounding the reported Emirati deal is widely discussed. “The BCL debacle has ruffled many feathers,” reports an international trader from the capital. “There are multiple theories flying around.”

The Russian company’s legal papers make a fresh offer. Addressing Attorney-General Morulaganyi Chamme last week, Norilsk Nickel said: “The Government is now invited to engage constructively to resolve these matters”. According to CEO Marriott, “Botswana has a reputation as one of the safest and best places to invest in the whole of Africa and it has earned the strongest credit rating on the continent on that basis. The way that the government of Botswana has acted over BCL brings the validity of that reputation into question. The negative ramifications could be felt across the economy of the whole country.”

Leave a Reply