By John Helmer, Moscow

At your peril, the one thing you must never say to a ranking Israeli intelligence officer, even one in mufti or retirement, is that he is suffering from a superiority complex. For the clinical symptoms of the affliction include conceptual deafness, ideological blindness. These stem from the frontal-lobe idea that the victim earned victory over his adversaries by his own wits; that those wits are unbeatable; and that accordingly he can never be bested or made to look stupid or act the fool.

In strategy, this leads to the first law of Barnum (of American circus fame) – there is a sucker born every minute. The second Barnum law is that the first starts with yourself.

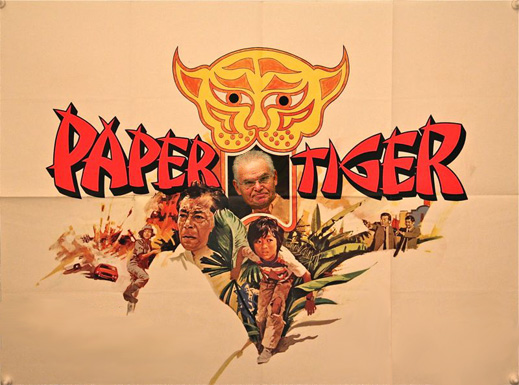

Edward Luttwak (image centre), a Transylvanian by birth, may (or may not) have spent training time in israel that is missing from his curriculum vitae. He’s been a favourite consultant of strategists there, and at the US Defense Department, the highest ranking of whom are named in the thank-you section of Luttwak’s latest book, It’s a reworking, he says, of a report the Pentagon paid him to deliver on the strategic options for dealing with China.

The scope of the book is indicated by Luttwak’s allocation of his mighty expertise – a full chapter, 17 pages, is written on Australia; another chapter, and 11 pages, on the Philippines; on Russia, less than 3 pages.

This is the clue to Luttwak’s big idea: China is doomed strategically, he says, by virtue of the contradictions in the mentality of its leaders – faults which the United States and a coalition of hangers-on (Australians, Filipinos, Japanese) can winningly exploit so long as they resist the temptation to become as arrogant and as threatening as the Chinese themselves.

This is a full-blown case of the superiority complex. So perhaps it’s inevitable that Russia – China’s neighbour, nuclear-armed, largest energy producer in the world, supplier of raw materials and military technology, ally in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO, 上海合作组织) — gets such short shrift. If this is what Luttwak’s client, the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment thinks, not to mention the more secretive branches, and they will prove successful in overcoming the points of American view which Luttwak derides – State Department confrontation, Treasury Department appeasement — the Chinese (and Russian leadership) may comfort themselves that the paper tigers are straining at their stools.

Luttwak’s case is that China will inevitably grow stronger economically. And if that is accompanied by its military strength and projection of political (diplomatic) power, the Chinese are bound to stimulate adversarial reactions by those threatened. This negative alliance will form around the US, and turn into a strategy of containment. “It is the logic of strategy itself that dictates the impossibility of concurrent advances in all three spheres: inevitably, China’s military aggrandizement is already evoking countering responses”.

One reason the obviousness of strategy isn’t plain to the Chinese is, first of all, because Luttwak’s expertise on Chinese history and certain high-level Chinese officials he names as friends, judge that the Han race is good at cooking and art, even technology (computing, fireworks), but it is hopeless at warfare. This is because their “disabilities are compounded by delusions of supreme strategic wisdom vouchsafed by ancient texts.”

Luttwak’s reading of those texts has also discovered that when it comes to bribing enemies, clinching friends, or striking bargains for things of value which China needs, Beijing is forever in the grip of an outmoded “tributary system”, based on tactics of “barbarian handling”, the basis of which is profound contempt for the inferiority (unwashed, unwise, unstable) of the target. This is a twist on the idea flogged regularly in the Anglo-American media that with Africa’s resource-rich leaders, China is making gains because it is offering bigger bribes than the Americans, British or French, who’ve been hobbled by their respect for human rights and their anti-corruption statutes.

Luttwak’s evidence doesn’t extend to fieldwork he or his friends have actually carried out in Africa. He sticks closer to home; in fact to Stanford University in northern California, where Luttwak uncovered a tell-tale, one-day “Tianxia Workship [on] Chinese perceptions of World Order” in May 2011. This was sponsored by “the Chinese National Office for Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language, a cultural propaganda arm”. That, according to Luttwak, got “the opportunity to attack core Western values to promote a China-centered vision of international relations…with Stanford itself footing most of the bill.”

Luttwak may be envious of the stipend; he can’t be ignorant of the parallel operations of the British Council, Alliance Francaise, and the US National Endowment for Democracy (2012 budget, $118 million).

But his purpose on the Pentagon stipend is to persuade his client, and the broader western alliance, that with China bent on hegemony, there is little prospect of internal Chinese dissent and democratization to slow down the growth of military power. So, scratch the State Department’s strategy of confrontation over human rights. Chinese officials may say things which, according to Luttwak, are “dismissive”, “arrogant”, “brusque”, “threatening”, and “provocative”, but this, he says, only proves how mentally challenged they will prove to be, if the resistance follows the Luttwak recipe.

Luttwak doesn’t let clumsy mistakes get in the way of this argument. His big clue to the inevitable Chinese threat is “the great absence in “China’s National Defense in 2010”, the dog that did not bark in “The Hound of the Baskervilles””. Wrong dog, wrong clue. In Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series, the dog that didn’t bark gives the game away in The Silver Blaze. The hound in the Baskerville tale is a barker, a biter too, and a fake.

A strategy of cooperation and appeasement, as evidenced by the Stanford workshop and the US Treasury’s promotion of Chinese economic growth, should also be scratched, according to Luttwak, because it corruptly “makes cheap capital available to US public and private finance.” The corruption lies in the featherbedded link between US Treasury staff and their former, current or future employers doing business with Beijing.

What does that leave for options? Luttwak concedes it won’t be possible to outspend the Chinese, or outfight them (if escalation reaches the nuclear weapons trigger). The occasional puppet, ethnic, island, or border war is recommended, along Middle Eastern lines, more as an incitement to the People’s Liberation Army, and as a propaganda tool to synthesize anti-Chinese sentiment in the rest of the world.

But at bottom Luttwak is backing the Pentagon in an alliance to contain China on a global scale, cut its economic growth rate in half or more, and starve the domestic Chinese economy of the funds to pay for military expansion. The methods proposed include “restricting Chinese exports into their markets, denying raw materials to China insofar as possible, and stopping whatever technology transfers China would still need.” Recruits for such an American “geo-economic” strategy include midgets like Australia, whose export income is dependent on mineral exports to China, and tourism and educational services with the Chinese; bankrupt war criminals like the Japanese right-wing; Vietnam and Mongolia.

It doesn’t occur to Luttwak that if Australia tries to curtail its exports to China, Russia will fill the gap, and earn the premium on rising commodity prices which American strategy has already provided by its hapless warmaking in the Middle East over the past two decades.

Russian strategic doctrine clearly treats trade embargoes, financial sanctions, and naval blockades as acts of war which cannot be justified except by such collective security bodies as the United Nations. Russian strategy is also explicit that an attack — military or economic — on one member of the security collectives to which it belongs may be a cause of war for all.

Luttwak goofs again, claiming Japan might be game for a Russian ally to take the place of China: this, says Luttwak, is because Japan never attacked the Soviet Union and was the victim of Soviet attack itself in 1945. Apparently, Luttwak has missed the Japanese war of May to September 1939, Japan’s defeat by Generals Georgy Zhukov, Grigory Shtern, and Yakov Smushkevich at the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, and the Japanese capitulation on September 15, 1939. Had the German attack in the west managed to take Moscow and St. Petersburg, the Japanese are likely to have tried again their so-called Northern Doctrine for occupation of Siberia. As things turned out, Moscow’s victory in east and west led the Japanese to aim their warmaking eastward and south — at the US Navy, at the British colonial bases, and at southeast Asian sources of raw material.

Russia has this, plus the earlier lessons of the defeat by the Japanese Navy in 1905 – assisted then by the British, Germans, and Americans – as a reminder that hegemony in the Asian-Pacific theatre should always be denied to everyone. Accordingly, the driver of Soviet and Russian strategy remains the aggressive expansion of the Americans, with their allies.

This isn’t to say that Russian strategy is blind to the potential for Chinese threat. It’s just that in the Russian calculation of likelihood of danger, priority, and timing, the US and its allies come first. NATO is the only military threat identified by name in The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation, issued by the Kremlin in February 2010. According to the naval version, the Russian Maritime Doctrine for 2020 – published in July 2001 — the concern for China is implied. “The significance of the Pacific coast to the Russian Federation is enormous and continues to grow. The Russian Far East has huge resources, especially in the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, while sparsely populated and relatively isolated from the industrialized regions of the Russian Federation. These contradictions are compounded by the heavy economic and military development of neighboring countries in Asia Pacific, providing a very significant impact on economic, demographic and other processes in the region.” But China is also included on the list of Russian strategic allies to deter and prevent military conflict.

Containment of China, as recommended by Luttwak and his Pentagon friends, isn’t new, but the case for it gets clumsier, and without the communist bogey, more racial in tone.

Vietnam is a special case – a traditional rival of China, which has defeated the French and the Americans, and fought a Chinese invasion force to a standstill in 1979, the Vietnamese don’t qualify for Luttwak stooges in a US-led plan of containment of China. The Vietnamese also say they stand to gain from a multiplicity of military deployments in the region up to the level of aircraft carriers. If Russia grows in military strength and presence, including the reopening of the Camh Ranh naval facility to Russia’s Pacific fleet, the less likely any single state will emerge as hegemonic and threatening to all. In its latest version, Russian naval strategy appears to concur – the more aircraft carriers, the merrier.

Dwarves on the shoulders of giants like Australia are viewed in Russian strategy as nothing but stooges for US hegemonic strategy; they are also stooges because they are trapped by the limitations of an economic dependence on China from which there can be no American rescue. Although Oleg Deripaska’s Rusal has a stake in northeastern Australian alumina and Vladimir Potanin’s Norilsk Nickel a stake in western Australian nickel, their commercial significance has been stagnant, their political influence minimal. So Russian strategic interest has shifted to the Pacific islands.

Luttwak acknowledges that “if a China/anti-China world does emerge…Moscow would be its strategic pivot, conferring much leverage to its rulers, who would certainly use it to the full.” But so bent is Luttwak on furthering the case for economic war against China, he recommends a scheme of buying off the Russians with gifts from Japan. ‘Barbarian handling’ is apparently an uncivilized throwback when practised by delusional Chinamen, but clever if the Japanese try it “to enlist the Russian Federation for the anti-China coalition – indeed, it could do more than any other country.” Luttwak also recommends that Japan forgive and forget “patently dishonest revocation of contracts” (Gazprom’s takeover of the Sakhalin-2 project), the Kurile Island dispute, etc. In Luttwak’s scheme of things, the Russians are only waiting for the Japanese to arrive with suitcases of cash.

That there is a well-developed Sino-Russian strategy of collective security and cooperation isn’t apparently known to Luttwak, or his Pentagon pals; without mention in the book of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Luttwak aims to convince his soldier and sailor readers they need not look beyond his pages for all they need to know about their enemies, and the means to overcome them.

This “state autism” as Luttwak sees everywhere but his own head is convenient for Russia, if it remains convincing to the Americans. There is a 3rd Barnum law, by the way. It’s that the best disinformation agent is the fool with rank (retired).

Leave a Reply