By John Helmer, Moscow

The old oligarchs, and several new aspirants, have a new playground in the Russian transportation sector, where their profits are guaranteed by the state budget. Carrying cargo from mine and wellhead to plant and port, and back again from port to market, is already profitable in conventional terms, and so the state assets, once part of the state railways monopoly, are the target of active lobbying for special favour. Carrying passengers around the biggest conurbation in the country – Moscow – is another target. But because passenger fares are regulated and subsidized by the state, the profitability of transporting them is more restricted than cargo transportation. It is also better hidden. Still, the game rules for privatization are the same as they were in the natural resource, energy and mining sectors – buy cheap (corruptly), sell dear (offshore).

In general, purchasing assets from the state on the cheap means the acquiescence of state officials in low-ball privatizations, or non-competitive “strategic placements”, paid with state bank loans on soft securization terms, subsidized interest rates, non-market repayment guarantees: everyone knows these are administrative measures requiring extras.

There is also the brand-new invention of the specialized holding which combines inside trading with public money, the tricks of market underwriting (greenshoe options) and exemptions from full disclosure (gumshoe options). In London, this is what you would get if Prime Minister David Cameron nationalized the operations of Nathaniel Rothschild. In Moscow, it’s called the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), a spinoff from Vnesheconombank (VEB) which started business on June 1, 2011.

For London and New York fund managers and investment banks, the opportunity is to establish equity positions at a low entry price arranged by the Russian partner; and then cash out at IPO time when the value can be rigged to earn a sizeable multiple. If that sounds like a hornet’s nest, it is.

One way to avoid getting stung is to find a private alternative to the initial public offering (IPO) route, and thereby limit disclosure to foreign market regulators of beneficial owners, costs, earnings, related party transactions, and real rates of return counted according to international financial reporting standards.

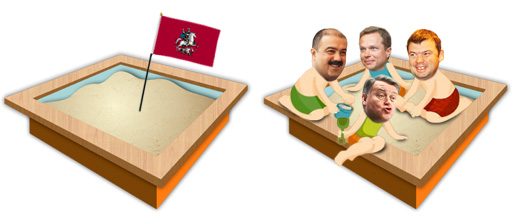

Monopolization fits the bill nicely. One of the Russian masters of this alternative route has been Iskander Makhmudov (sandbox far left), who started his asset accumulation career as a protégé of Mikhail Chernoy (Cherney) in the early 1990s. Unpublished evidence assembled by Cherney for his UK High Court lawsuit against Oleg Deripaska last year shows Cherney had helped Makhmudov acquire control of copper and coal assets, loaned him money, and shared the profits offshore. Makhmudov has acknowledged the relationship. “I have known him since the beginning of the 1990s…We are friends.”

Last September Makhmudov demonstrated how friendly they could be when he persuaded Cherney to accept $200 million in six annual instalments instead of full repayment of an overdue loan of $450 million.

Makhmudov was just as friendly when he persuaded the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS) to allow him to transfer his monopoly of Russian locomotive manufacture into an Amsterdam-registered entity called Breakers Investments. FAS took just 11 days from November 8 to 19, 2007, to study the scheme, and approve it. Without the weekends, that was just six working days.

This is a record FAS appears determined to break. As Makhmudov has been assembling another virtual monopoly on the railways, this time of passenger transportation, a source at the transportation section of FAS said this week that it has conducted no competition analyses or takeover approval reviews. That’s zero working days.

The 2008 statute which imposes special restrictions, notifications and approval procedures for foreign-owned companies to acquire strategic Russian assets, defines “manufacturing of aviation equipment” as strategic. If the equipment doesn’t fly, but instead speeds across the ground, it seems not. At least, that’s what Article 6 of FZ-57 implies. FAS spokesman Anna Orlova goes further, referring to Sect 36 of Art. 6, in order to claim: “Only the subjects of a natural monopoly, i.e. the company [State Railways Company, RZhD], are considered as strategic, but not passenger transportation railways, etc.”

Actually Sect 36 says more, tying the strategic tag to “services offered by an economic entity which is included in the Register of the subjects of natural monopolies in the sectors specified in Clause 1 Article 4 No. 147-FZ Federal Law of 17th August 1995 «On Natural Monopolies», except the subjects of natural monopolies in publicly accessible electric communication, publicly accessible postal service, services for heat energy transmission and electric power transmission through distribution networks.”

FAS takes the view that once RZhD starts peeling off its assets and selling them, the spinoffs cease to be strategic, and that applies to Makhmudov’s passenger rail companies, as it recently applied to RZhD’s cargo units which have been privatized to Sergei Generalov, Vladimir Lisin, and Vladimir Yevtushenkov – that is, Transcontainer, Freight One, and SG-Trans.

As Makhmudov quietly put together his portfolio of passenger rail assets in the Moscow area, it has barely registered in public how extensive his control of the market segment is becoming. A circumscript history of the acquisitions and itemization of the assets appears on the website of one of Makhmudov’s holdings, Trans Group. This reports initial licensing for passenger transportation in October 2003, followed by the start of “Russia’s first private electric train”, Transexpress between Moscow and Kaluga, in March of 2004. There is passing mention that the group owns the Moscow-Tver elektrichka; L-Express, which runs between Riga, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Minsk; and Aeroexpress, the rail link between downtown Moscow and the airports of Sheremetyevo, Domodedovo and Vnukovo.

Makhmudov’s company claims its experts are working on a 5-year plan to 2015 for the “development of high-speed passenger traffic on the territory of Russia and internationally; studying the prospects of development of joint business in the sphere of passenger traffic with other railroads of Russia affiliated with RZhD; [and] participation in the formation of suburban passenger companies in the regions.”

The Moscow Passenger Company has no website and contact details are unpublished. The shareholding is veiled, and the financial reports withheld. Aeroexpress reports (page 52) that Makhmudov holds 17.5% of its shares, his protégé Andrei Bokarev (sandbox far right), 7.5%, and a front company, Delta-Trans-Invest another 25%. RZhD, run by Vladimir Yakunin (sandbox centre bottom) holds the other 50%.

Omitted from these limited disclosures are two major market expansion moves. In 2011, the Moscow Passenger Company, which Mahkmudov also owns with Bokarev, bought a 25% stake of the Central Suburban Passenger Company (TsPPK). This company carried more than 503 million passengers in 2011, taking a 56% share of the market for suburban Moscow ground transportation. TsPKK’s revenue that year has been reported at Rb24 billion ($781 million). RZhD’s Yakunin let it go for just Rb21 million ($683,594). Yakunin is also a partner of Makhmudov’s as RZhD holds a 25% stake in Breakers Investments.

Last month, RZhD sold to Moscow Passenger another 25% of TsPPK, and thus the control stake, for just over Rb820 million ($27 million ). This was much more than the earlier deal, but the control premium is still considered a steal by independent transport analysts in Moscow.

In the second major move, Makhmudov came close to persuading the Moscow city government to award him a Rb8 billion ($260 million) contract to build 120 new trams. The vehicles were to be designed by Alstom of France, another stakeholder in Makhmudov’s Breakers Investments, and constructed by a joint venture for the purpose, TramRus, set up between Alstom and Makhmudov’s locomotive holding, Transmash.

Supervising the tendering a few days after it had commenced last August was the freshly appointed deputy mayor in charge of transportation, Maxim Liksutov (sandbox centre top). According to the announcement of the city government, Liksutov’s appointment came through on September 25 That was just weeks after Liksutov had been in charge of arranging Makhmudov’s tram construction bid with the city government.

The 36-year old Liksutov has been a protégé of Makmudov for years. After graduation and employment at two anonymous entities called MTK-Trans and Worldwide Invest, in 2005 Litsukov went to work at Trans Group, and then ran both Aeroexpress and the Trans Group holding, receiving in reward from Makhmudov some shares. These were sold when he moved over to the Moscow city government.

Litsukov’s decision to serve the public interest was a modest sacrifice of his business talent. According to Russian rail industry expert Alexei Bezborodov, the share buyback deal with Makhmudov and Bokarev left Litsukov with a golden handshake of “a few hundred million dollars, but less than the Forbes estimate of $500 million.” Bezborodov called Litsukov “a rich Pinnochio”.

Litsukov’s decision to serve the public interest was a modest sacrifice of his business talent. According to Russian rail industry expert Alexei Bezborodov, the share buyback deal with Makhmudov and Bokarev left Litsukov with a golden handshake of “a few hundred million dollars, but less than the Forbes estimate of $500 million.” Bezborodov called Litsukov “a rich Pinnochio”.

The city’s transportation department had set a ceiling price for the new trams of Rb9 billion. But there was just one other bidder, Ust-Katavsky Railcar Plant in Chelyabinsk. When asked if it believed the tender had been rigged in Makhmudov’s favour, a spokesman for Ust-Katavsky said this week it was best to ask the company’s trading house in Moscow, which had been engaged in negotiations with the city. At the trading house office, a source said the management wasn’t talking for the present.

Also excluded from last year’s bidding by the city government was Sinara, a company owned by Dmitry Pumpyansky’s TMK steel and pipemaking group. It had been trying for the tram contract with Siemens designs and technology. Sinara is refusing to comment on the circumstances.

State-owned Uralvagonzavod (UVZ) has proved a more resourceful rival for Makhmudov. Based in Nizhny Tagil (Sverdlovsk), it is the largest builder of main battle tanks in the world. Civil vehicles like railcars, tractors and other vehicles comprise roughly 60% of its output and sales. It has complained at anti-competitive pricing and other monopolistic practices by oligarch-owned steelmakers like Evraz in the past, and won. After the new tram tender was launched, UVZ, partnering for design and technology with Bombardier of Canada, complained to the FAS.

When FAS spokesman Orlova claims there has been no review by her agency of Makhmudov’s business practices in the transportation market, she is speaking precisely and literally. But the review FAS conducted last August of the Moscow city government’s tram tender found the city government was at fault. “The [tender] terms lacked details that have a substantial effect on the price and quality,” FAS was quoted in Moscow media last August. The tender documents failed to specify how many sections the new-design tram door should have, the FAS announced, and it omitted a requirement that the new tram should be able to plow away snow on its tracks. On August 10 the FAS ordered the tender withdrawn and the bidding stopped until new terms were published. That allowed UVZ to bid again. At the same time, the FAS dismissed complaints from UVZ and others that Liksutov had been involved in rigging the tender in Makhmudov’s favour.

At the time Bombardier’s Moscow spokesman Paer Isaksson said tongue in cheek that the company was “committed” to the Russian market and looked forward to “deepening the cooperation with our partners.” Bombardier has been choosy in those partners, delaying acceptance of a proposal from Oleg Deripaska’s holding to join his aviation unit Aviacor in building short-haul turboprop aircraft. This time round, however, Bombardier’s combination with UVZ has defeated Makhmudov.

On December 17, the Moscow city government announced that Makhmudov’s second try has been beaten by UVZ and Bombardier. Makhmudov offered Rb8.505 billion ($283 million); UVZ bid Rb8.46 billion ($281 million). A press statement by UVZ’s deputy director, Andrei Shlensky, claimed the win was gratifying but the tender offer would leave UVZ with limited profitability.

The trick in this game is to multiply the number of “limited profitability” injections from the city budget until the combination, unreported in the Moscow city budget papers and unaccounted in company financials, becomes a full-scale transfusion. According to an announcement from Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin in November 2011, the city plans to spend Rb1.6 trillion ($52 billion) on transportation infrastructure by 2016. That’s the pot Makhmudov’s group is chasing. It is large enough to include money to revive the largely discredited monorail in southern Moscow, as Litsukov must decide whether to overturn an earlier decision by Yury Luzhkov’s administration to shut the monorail down for lack of passengers and heavy costs. Last July he announced that he was postponing the shutdown for at least three more years. An investment bank source in Moscow claims Makhmudov controls the monorail company through a spinoff privatization from the Moscow Metropolitan.

Shlensky of UVD forecasts an intensifiying competition with Makhmudov over the tender for new underground trains for the Moscow Metro, to be decided in a year’s time. Makhmudov and Bokarev have already moved on the Moscow Metro, acquiring MosMetroStroi (MMS), the company which constructs the tunnels and lays new lines. They paid an estimated Rb7.6 billion ($245 million) for the city’s 100% shareholding in December 2010. MMS had reported annual revenues of Rb23 billion ($740 million) for the year earlier, and was carrying debt of Rb6.4 billion ($206 million). The FAS quickly cleared the takeover in February 2011, but a claim of rigging by a defeated rival went to the Moscow Arbitration Court. It ruled on November 2, 2011, that there was no evidence of award violations or corruption, and allowed the takeover to be finalized.

Until last month’s tram tender victory by UVZ, Makhmudov appeared to be holding the master key to the lockbox of state funding for Moscow passenger rail transportation. He also appeared powerful enough to deter FAS from direct confrontation over the use, or abuse, of Trans Group’s dominant position in the market. But will competition from UVZ and others make the financial picture more transparent, and the assets more accessible to a wider range of investors?

So far as Moscow investment bankers specializing in transportation are aware, no study has been compiled to show a sum-of-parts valuation for Makhmudov’s railway assets. One Moscow-based American analyst believes such a valuation is impossible. “All the financials are non-transparent. You don’t have any idea of what the real profitability is.” He concedes that Makhmudov’s takeovers may generate profits even if under state control the railways were run at a loss. “Sometimes assets are loss-making under state control; that’s why they are sold for cheap, but [after privatization] they then generate a big profit. I would say that with the chance of new electrichki coming this year, there is a good chance that more people will take them, and thus make the business more profitable.”

Alexei Rybakov is a Moscow transportation analyst who covers these as yet unlisted companies at TradePortal.ru. This is a property of Bank Rost whose shareholders appear to be independent of Makhmudov’s group. “Do not forget,” says Rybakov, “that Iskander Makhmudov is engaged not only in passenger transport, but also in production [of rolling stock]. So if we separate the transport companies, and if we divide RZhD, then the entire service staff, and all production, are tied directly or indirectly to Iskander Makhmudov. This includes Aeroexpress, TransMashHolding, and TsPPK.

“Therefore, in this case, his role is clear. Russia is a still a fairly large country, with low consumer demand, and where rail transportation, freight transport as well as passenger, will still be used with strong enough demand. This will be the case even taking into account the hypothetical that the Russian economy and the global economy will not be operating optimally. Even if we take the most simple statistics that we have, and look at the traffic on the Moscow node, according to statistics for the 8 million jobs that we have in the capital area, 5.5 million [69%] of them come from localities near or around Moscow. So passenger transportation will develop positively. Also, it is necessary to give credit to the fact that for the last two years TsPPK is showing positive profitability. It closed its last two years in the black. This is facilitated by a number of factors — increasing efficiency, reducing costs, plus increasing revenue.

“Iskander Makhmudov has pursued quite serious lobbying interests. And, basically, he is winning now. Tariffs have been reduced, as far as I know, for the use of infrastructure. As I recall, he was very good at retaining [state-funded] subsidies. Here I believe that subsidies should have been shifted to the Moscow region, but in the end they were left in Moscow [city].”

Leave a Reply