By John Helmer, Moscow

Russia has grown up; Derk Sauer (lead image), boy scout for American, Dutch and NATO plots for Kremlin regime change since Boris Yeltsin left office, can’t.

Under cover of Russian frontmen, he has bought back the Moscow Times, and put his son Pyotr in charge of opinion. The opinion is the same as it was when Sauer started in Moscow in 1992. Mark Ames, the scourge of Moscow Times duplicity then, says now: “They’re trying to make the MT even more boring than it ever was, with just a hint of standard Moscow liberal politics. Right now Derk seems like a garden gnome I dreamed about long ago.”

Sauer started the Moscow Times on a shoestring in 1992. He recovered it with a shoestring in 2017. For details of his start, read.

Owner of the shoe from whose string Sauer has dangled for this interval have included investors connected to the US intelligence services (he admitted to me himself); a Swiss entity owned by Mikhail Khodorkovsky; Vladimir Potanin, the Norilsk Nickel oligarch; a Dutch media conglomerate, VNU; a Finnish media group called Sanoma, together with the Murdoch media group and Pearson’s, when it owned the Financial Times of London; then a Russian journalist without money, Demian Kudryavtsev. He appeared when Sauer and his offshore partners surpassed the 20% maximum foreign ownership threshold enacted in the amended Russian Law on Mass Media (N 305-FZ) in October 2014; the measure took effect from January 2016. Kudryavtsev has claimed he made the acquisition with the “moral support” of the coalmine operator, Dmitry Bosov.

MONEY AND MORALS — THE MOSCOW TIMES’S SUPPORTERS

Left to right: Mikhail Khodorkovsky (in Moscow before his arrest in 2003); Rupert Murdoch (in St. Petersburg to meet President Vladimir Putin, 2005); Pekka Ala-Pietilä, Sanoma board chairman since 2014; Dmitry Bosov; his role in financing Kudryavtsev is reported here.

Sauer followed the advice of lawyers on how to restructure his Russian media operations “to divide the business so that the editorial and broadcasting activities are controlled by a Russian entity and the remaining part of the business remains foreign-controlled, e.g. separating the roles of the so-called founder (registration as mass media in Russia) and the editorial office/broadcasting entity, on the one hand, from the publisher being in control of the remaining business streams, on the other hand.”

Meantime, Mikhail Prokhorov employed Sauer in his RBC media group, until he was ousted in 2016. There was internal criticism of Sauer’s financial operations at RBC, followed by a police raid and threatened indictments for fraud. For the story of the fraud and other allegations against Sauer, click to read. He claimed he was forced to flee to The Netherlands for political reasons connected to Prokhorov’s presidential campaign against President Putin. Sources with access to RBC’s accounts do not substantiate that version. An independent media investigation by Meduza reported that RBC became unprofitable when its “shadowy sources of income” dried up.

The financial collapse at RBC was the largest of Sauer’s loss-making businesses. The Moscow Times had also run up sizeable debts at VNU; more at Sanoma. When Kudryavtsev took over, Sanoma reported a non-cash transaction for €8 million in value for shifting Sauer’s debts off the Sanoma balance sheet. How much of the debt accumulated at the Moscow Times isn’t known. Sanoma, like the Dutch VNU earlier, had been unable to dispose of it and cut its other Russian losses for several years. Sauer has been unwilling to explain how he (or who) underwrote the losses.

In 2017, after Kudryavtsev, an Israeli, lost his Russian citizenship and transferred the Russian daily Vedomosti to his wife, Sauer returned. Sauer’s authorized version claims the Moscow Times became the operation of a Stichting 2 Oktober, Dutch charitable foundation in which he, Kudryavtsev and Sauer’s wife were in charge; then they devised a shareholding arrangement between a Chinese-Russian named Vladimir Jao (Zhao) with 51%; a Sauer trustie named Svetlana Korshunova with 30%; and with 19%, Sauer himself.

Jao (right) is reported in the Moscow press as the operator of a catering business called  Aeromar, a joint venture owned by Aeroflot and Lufthansa to supply meals for commercial airlines and shops at Moscow airports. In 2016 it reported a profit of Rb874 million ($14.3 million). Jao also operates a Moscow club called, after himself, Chinese Pilot Jao Da. “It is basically a big, dirty student den and as such makes a great venue for getting drunk”, reports a current review.

Aeromar, a joint venture owned by Aeroflot and Lufthansa to supply meals for commercial airlines and shops at Moscow airports. In 2016 it reported a profit of Rb874 million ($14.3 million). Jao also operates a Moscow club called, after himself, Chinese Pilot Jao Da. “It is basically a big, dirty student den and as such makes a great venue for getting drunk”, reports a current review.

Sauer has described Jao as his friend and partner who “doesn’t control the publication”. There is no substantiation for Jao’s capital contribution, if any, through a Russian front company called Tiemti. The Russian word spells out TMT, Sauer’s acronym for The Moscow Times. Since Kudryavtsev passed the financial liabilities of the publication from the Dutch foundation to Tiemti, it has been Sauer who has been financing the balance of the debt and the accumulating losses.

Sauer’s son Pyotr, a dual Russian and Dutch citizen, is listed on the publication’s website as an editor. Another listed editor, Eva Hartog Skorobogatova, reports herself as a current journalist in Moscow but former editor of the publication. Hartog is also a Dutch citizen.

Left to right: Pyotr Sauer on Twitter; Svetlana Korshunova on Facebook; and Eva Hartog Skorobogatova on Dutch television.

The loss-making of the Moscow Times has required subsidization from the start. That has produced another consistency in Sauer’s media career – promotion of US and NATO propaganda for Boris Yeltsin until 1999, and since then of regime change at the Kremlin. While US law in the past has prohibited US journalists working for US media from operating on CIA or State Department funding for information gathering or disinformation circulation, the restriction hasn’t applied to Americans working for foreign media, or to foreign journalists. The Moscow Times has been that type of operation. Celebrating the publication’s tenth anniversary in 2002, then US Ambassador Alexander Vershbow wrote of Sauer’s “marvelous job chronicling Russia’s transformation over the past decade.”

As Sauer moved back into management, his editorial line has favoured the NATO and Dutch Government version of the Malaysia Airlines MH17 disaster; and the Bellingcat version of the Skripal case. According to Sauer junior, “the Skripal case has served to remind readers that, against the odds, there is still an appetite in Russia for investigative reporting. It has also begged the question of how long the Kremlin will allow it to continue.”

His website has proposed Ukraine as a model for presidential election campaigns in Russia; Council of Europe supervision of Russian human rights; and endorsement of State Department sanctions against Russia. Anti-Russian campaigners like Leonid Bershidsky, the Israeli Zev Chafets and Bruno Macaes, a Portuguese politician employed by a US think-tank, are regular contributors. The Moscow Times is the only publication in the country to refer to the “annexation” of Crimea in 2014.

Source: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/

Pyotr Sauer has posted a curriculum vitae in which he describes his career before joining the Moscow Times in August of last year. His previous job, he says, was at the London-based Control Risks organization, founded and run by retired British Army, SAS and UK Government officials. According to Sauer, at Control Risks he was “Research Analyst. Compliance Forensics and Intelligence (CFI). Former Soviet Union.” That was in 2017 and 2018. In 2016, he was “Research Officer- Political Affairs Embassy of the Netherlands in Azerbaijan.” With university degrees from Utrecht and University College London, Sauer also identifies his association with the Organization for Security and Economic Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the International Crisis Group, and Amnesty International.

Source: https://nl.linkedin.com/in/pjotrsauer/de

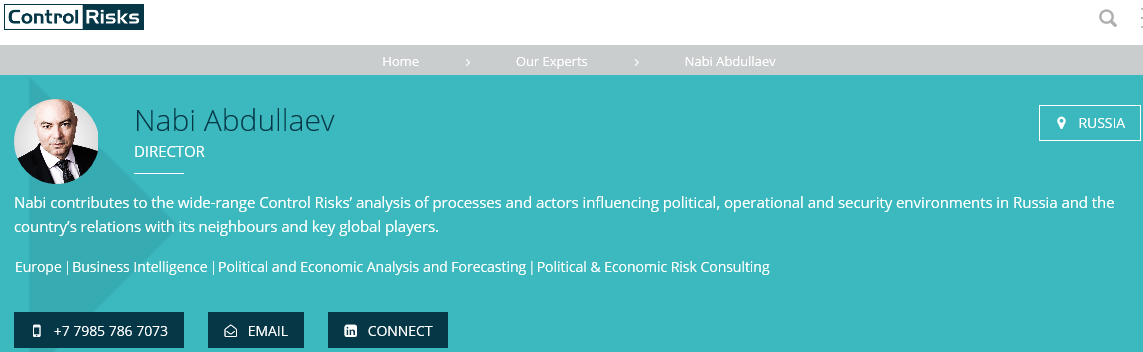

The connexion between the Moscow Times and Control Risks isn’t coincidental, as there is more than one of them. Nabi Abdullaev was one of Derk Sauer’s editors at Moscow Times until 2015. When Sauer replaced Kudryavtsev, Abdullaev began appearing on the Moscow Times website until the end of 2018. Now, he and Control Risks say, he is a director in the Moscow office of the outfit.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Source: https://www.controlrisks.com/ The company résumé says: “Prior to joining Control Risks, Nabi was the chief editor of The Moscow Times, an English-language daily newspaper in Russia, where he was a political and security writer for many years… Nabi has a Master’s degree in Public Administration from Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government where he studied negotiation and conflict resolution.” Tim Stanley, British, runs the Moscow office. The third staff man identified on the company website is Yevgeny Gordeichev, a British government employee. The company website says this about him: “Yevgeny worked at the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office, where he divided his time between the British Embassy in Moscow and British Consulate in Yekaterinburg. During this time he worked as a Risk Assessment / Immigration and Liaison Officer alongside international law enforcement agencies to investigate crimes such as immigration fraud, document forgery, illegal facilitation and human trafficking. Yevgeny has also worked on a number of short-term assignments for Schlumberger Inc. as a head of its subcontractor visa and immigration compliance department and as a Country Security Advisor at the OSCE (Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe) during the 2012 Russian presidential elections.”

Abdullaev was telephoned and emailed at his office. He was asked how the relationship with Control Risks contributes to the journalism of the Moscow Times. He refused to answer.

Are Sauer and his TMT a target for the new amendment to Article 19.1 of the Mass Media Law which is in review this month by government officials, as well as by members of the State Duma. Follow the details here.

The new amendment was prompted last year by concerns that the foreign ownership limit enacted between 2014 and 2016 isn’t extensive enough to cover internet aggregators moving translations of stories from foreign-controlled sources into the Russian audience. There is also suspicion in media business circles that Sberbank wants tighter restrictions to help expand its control at Yandex, since the two commenced a joint venture in internet retailing in 2017 to compete against Amazon.

The revision of Art. 19.1 was also forced by a ruling of the Constitutional Court on January 17. The court  had upheld an application by a Yevgeny Finkelshtein, part-owner of Radio-Chance (49%) and Russian Radio Europe-Asia (51%), and a dual-Russian Dutch citizen; read the ruling in full here. Finkelshtein (right) had argued, according to the court transcript, that the law “disproportionately restricts the right to private property, the right to judicial protection, and the right to freely transfer, to produce and disseminate information (without contributing to limiting the excessive influence of foreign investors on the broadcasting policy of the media); is discriminatory (putting citizens of the Russian Federation with foreign citizenship in a disadvantaged position compared to other citizens); is insufficiently defined (not allowing to establish what share of participation in the authorized capital of a commercial company organizing broadcasts is recognized as permissible).”

had upheld an application by a Yevgeny Finkelshtein, part-owner of Radio-Chance (49%) and Russian Radio Europe-Asia (51%), and a dual-Russian Dutch citizen; read the ruling in full here. Finkelshtein (right) had argued, according to the court transcript, that the law “disproportionately restricts the right to private property, the right to judicial protection, and the right to freely transfer, to produce and disseminate information (without contributing to limiting the excessive influence of foreign investors on the broadcasting policy of the media); is discriminatory (putting citizens of the Russian Federation with foreign citizenship in a disadvantaged position compared to other citizens); is insufficiently defined (not allowing to establish what share of participation in the authorized capital of a commercial company organizing broadcasts is recognized as permissible).”

In its ruling, the court judged that national security justifies the restriction of foreign information operations in Russia. The judges also agreed that the wording of the restrictions in the current statute is too ambiguous in interpretation and uncertain for application. They ordered that “the federal legislature shall – proceeding from the requirements of the Constitution of the Russian Federation and taking into account the legal positions of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation expressed in this Resolution — make the necessary changes following from this Resolution in the existing legal regulation.”

Leonid Levin, chairman of the Duma’s Information Policy Committee and a co-author of recent measures to stop “fake news” in Russian media, was asked to say if he considers Sauer and the Moscow Times a target of the proposed new amendment. He refused to say. Other deputies supporting the redrafting of Art. 19.1 are also determined to stay silent for the time being. Finkelshtein would not say what outcome he expects for his own radio stations, or for his fellow Dutch stakeholder in Russian media, Sauer.

Where Sauer’s money is coming from is the key. “Perhaps the secret is not in how but in why”, comments Ajay Goyal (right) , publisher and editor-in-chief of The Russia Journal, a strong rival of Sauer’s publication in the Moscow market. “The how is easy. The online newspaper costs just a fraction of a print publication and it can easily avoid Russian legislative restrictions on [foreign ownership of] print media. Why he has this need to continue to be the fountainhead of anti-Russian poison is a mystery. This country [Russia] has given him everything. Sauer was a nobody when he came to Moscow. He would have remained that in Holland. Russia has given him everything he has and yet he pisses on this country in every headline, every editorial and every opinion or news piece. Why is he doing it? Perhaps he is just bored. Perhaps the man has developed a serious case of hubris and he wants to do regime change in the Kremlin single-handedly.”

, publisher and editor-in-chief of The Russia Journal, a strong rival of Sauer’s publication in the Moscow market. “The how is easy. The online newspaper costs just a fraction of a print publication and it can easily avoid Russian legislative restrictions on [foreign ownership of] print media. Why he has this need to continue to be the fountainhead of anti-Russian poison is a mystery. This country [Russia] has given him everything. Sauer was a nobody when he came to Moscow. He would have remained that in Holland. Russia has given him everything he has and yet he pisses on this country in every headline, every editorial and every opinion or news piece. Why is he doing it? Perhaps he is just bored. Perhaps the man has developed a serious case of hubris and he wants to do regime change in the Kremlin single-handedly.”

“Or perhaps he senses another opportunity to get big money out of anti-Russia propaganda. There is that very juicy piece of fruit in info-warfare money from NATO, the EU and the State Department hanging low. There is no reason, Sauer thinks, not to grab it.”

Sauer and his wife, Ellen Verbeek, control the Stichting 2 Oktober — in Dutch stichting means a foundation — which is based in Amsterdam. Their purpose, according to the foundation website, “is to support independent journalism in Russia and the CIS countries. Freedom of the press and freedom of information are vital for gathering and distributing reliable, fact-based news. Media play a crucial role in providing citizens with free and unrestricted access to information that can help them monitor the authorities and make empowered decisions. In Russia, where the vast majority of the media is state-controlled, it is of vital importance that objective news and information remain available to everyone.

The foundation’s mission statement is more explicit: “Stichting 2 Oktober supports the activities of The Moscow Times. Founded in 1992, The Moscow Times was and still is an inspiration for generations of Russian journalists. With its fact-based, unbiased and objective journalism, The Moscow Times has a long and distinguished track record which in many ways set the standards for decent journalism in Russia. Until 2015, The Moscow Times published a daily newspaper. Today, it is primarily distributed through themoscowtimes.com and several stand-alone print products.”

The foundation acknowledges that the journalists working at the Moscow Times are paid by the Dutch Foreign Ministry:

Source: https://www.

Pyotr Sauer was asked to explain, since his publication appears to run no advertising, how its costs are paid for. He was also asked whether the Moscow Times or its writers benefit, directly or indirectly, from grants or other payments from non-Russian government sources, or from non-Russian NGOs? He refused to reply.

Leave a Reply