By John Helmer, Moscow

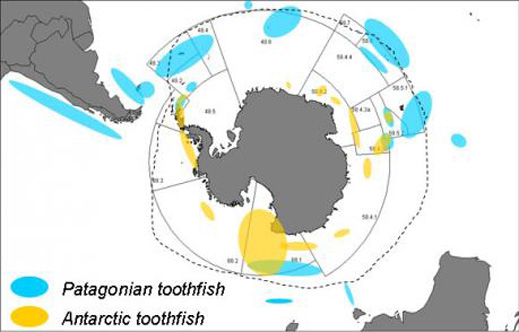

If you like eating river pike, apply to President Vladimir Putin who recently landed a big one (image left). If you like ocean seabass, this story is for you, especially if what your fishmonger calls Chilean Seabass is in fact toothfish; depending on how cold the waters are in which it is caught, this is either Patagonian Toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) or Antarctic Toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni – image right). The latter is mostly what you’ll eat if you buy zubatka (зубатка) in Russia.

There is another labelling problem with this fish. If you believe what Putin-hostile organizations like the Guardian of London and the Pew Trust of the United States report, the Russian government is responsible for standing alone against the rest of the world in order to block proposals to stop fishing in two areas of the Antarctic – Ross Sea, in the south of the Antarctic land mass, and along the eastern shoreline. In those areas toothfish comprise the biggest catch, followed by krill.

Two weeks ago, at a meeting in Bremerhaven, Germany, a special session of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was unable to agree on proposals for the two marine protected areas (MPAs). The commission comprises 24 member states plus the European Union (EU). The Ross Sea proposal had been submitted a year ago by New Zealand and the US; the East Antarctic proposal by the EU, Australia and France. Here is the Ross Sea MFA proposal. Note that according to section 7, introducing the no-fish, no-take rule in the Ross Sea ought not to “reduce the total allowable catch of toothfish or other species in the Ross Sea Region. Instead toothfish fishing displaced by the MPA would be redistributed to areas outside the MPA.” The summary of the East Antarctic MPA makes no such concession.

The proposals include maps pinpointing the areas to be covered by the sanctuary proposals.

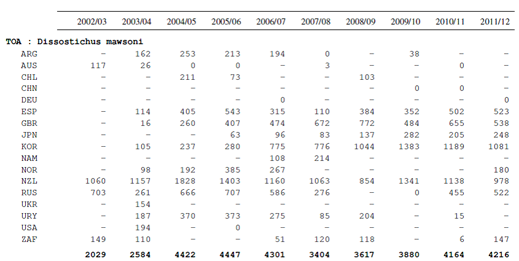

According to the available fisheries reports, the total catch of Antarctic toothfish has been rising sharply over the past decade. In 2011-12 it was 4,216 tonnes in total; about 85% of this (3,597 tonnes) came from the Ross Sea. According to the CCAMLR data, over the past decade the Antarctic toothfish catch has doubled. But the share taken by Russian vessels has varied markedly from year to year, and trails well behind other countries.

ANTARCTIC TOOTHFISH CATCH, BY YEAR AND BY ORIGIN OF FISHING FLEET

Source: CCAMLR

The table makes clear that the dominant country has been New Zealand, with half the tonnage in 2002; one-quarter last year. South Korea has overtaken New Zealand lately, and now catches between one-quarter and one-third. The British and the Spanish fleets rank third and fourth. Russia started the period with a larger proportion of the total, 35%; but its fleet has been unable to keep pace with its rivals in the Ross Sea; the Russian share of the catch was down to just one toothfish in eight last year.

What New Zealand would lose if the Ross Sea is put off limits to all toothfish trawling it is likely to gain from fishing in the replacement areas identified in the proposal. This is not so certain for the Russian fleet. Why the US, the French and the Australians, with no toothfish catch, would support the Ross Sea exclusion, is unclear – unless they too calculate that their fleets can exchange this giveaway for protection of fishing grounds they prefer.

The CCAMLR communique says the outcome of the Bremerhaven meeting was inconclusive: “Establishing MPAs is a complex process involving a large amount of scientific research as well as international diplomacy. Although CCAMLR members benefitted from the extensive exchange of views on MPAs in the CCAMLR Convention Area, agreeing on two major proposals for the establishment of MPAs proved to be a task requiring more time than was available during the two-day Special Meeting. The Meeting decided that further consideration of the proposals was needed. Therefore, there will be further discussions among Members until CCAMLR’s annual meeting in October 2013 when the proposals may be further discussed.”

According to the Guardian report, “Russia has blocked the creation of the world’s largest ocean reserves off the coast of Antarctica, in what campaigners called a ‘bad faith stalling tactic’… The Russian delegation…questioned the organisation’s legal mandate to create two huge Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) off the coastline of Antarctica. If adopted, the proposals would more than double the current area of protected ocean on the planet. Delegates to the meeting said that, while a Russian delaying tactic had been expected, the legal argument was ‘completely wrong’. Steve Campbell, campaign director of the Antarctic Ocean Alliance (AOA), said there was both procedure and precedent for the proposals: ‘It’s a very odd objection, because CCAMLR clearly has the legal authority to establish MPAs’.” The Guardian also reported: “The Russian delegation was unavailable for comment.”

A report from the Antarctic Ocean Alliance said: “Disappointingly, Russia blocked efforts to create two of the world’s largest ocean sanctuaries around Antarctica. Everyone, including the penguins, are devastated…In the end Russia, with support from the Ukraine, challenged CCAMLR’s legal authority to establish marine protected areas, leading negotiations to collapse. This was particularly frustrating because, unlike some international conventions, most nations came to CCAMLR in good faith to negotiate an outcome, including those countries that had concerns about the two.”

The alliance says it sent Putin a letter on July 13, after the Bremerhaven meeting had already begun, asking “that with your leadership Russia will support the Ross Sea and East Antarctica marine protected area proposals at the Bremerhaven meeting this week. We stand ready to assist in any way.” The alliance, based in Australia, appears to represent many international environmental organizations, including Greenpeace and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

The commission has already agreed on one MPA for the South Orkney area. That was accepted by all members, including Russia, in 2009. So why has Russia not agreed this time?

There is a longstanding Russian policy of opposing schemes by regional or sub-regional groups of countries to impose restrictions on navigation or use of areas in international waters. The underlying Russian reason for this is strategic security. Russia lost Baltic Sea access when the Soviet Union broke up, and faced potentially threatening restrictions at the Danish straits and at the Bosphorus. It has had to build new ports like Primorsk and Ust-Luga (Baltic), Taman (Black), Varandei and Sabetta (Barents, Karsk). Moscow’s sensitivity to restrictive schemes, using environmental conservation rationales, has grown in recent years when several Baltic states tried to oppose the construction on the Baltic seabed of Russia’s Nord Stream gas pipeline to Germany. Similar concerns have arisen in relation to Arctic waters where the US and NATO are viewed as trying to encroach on Russian sovereignty. The Turks use environmental rationales to justify attempts to restrict passage of oil tankers carrying Russian oil out of the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

The Russian government dismisses claims reported in the western media that it lacks the legal authority to challenge the MFAs proposed. The CCAMLR confirms that under the rules of the establishing convention of 1980, individual members can exercise a veto right. Article XII of the convention makes this plain: “Decisions of the Commission on matters of substance shall be taken by consensus. The question of whether a matter is one of substance shall be treated as a matter of substance.”

Dmitry Kremeniuk, head of the international cooperation department of the Federal Fisheries Agency (Rosrybolovstvo) in Moscow, was the principal Russian negotiator at the Bremerhaven session of the CCAMLR. In a communique issued after the meeting, the agency said it wanted “a more thorough scientific study of issues in the preparation of proposals for the establishment of MPAs in the Antarctic. Besides, the Russian side noted the lack of specific rules of international law on the organization and management of MPAs.” Sergei Gorbachev, spokesman for Rosrybolovstvo, said a more detailed analysis will be issued next week, including an itemization of the questions the Russians say the other CCAMLR members have yet to answer.

Other Russian sources describe the reason for the opposition to the Antarctic ocean sanctuary proposals at the CCAMLR as a combination of strategy and business.

Polina Zhbanova is the program coordinator for protected areas at the Moscow branch of WWF. She believes the Russian opposition stems from the fact that closing the Ross Sea to fishing would eliminate all Russian access to commercial quantities of toothfish. Because the domestic and commercial demand for the fish exceeds the supply, she says it is difficult for the members of CCAMLR to agree on a compromise. Zhbanova also believes that all the CCAMLR members consider commercial concerns as well as environmental ones.

“The Russian Fisheries Agency is quite concerned about the possibility of additional reduction in the area open for commercial fishing.” According to Zhbanova, “they are very wary of the prospects for the Russian fishing fleet in the Antarctic, if the [fishing] area will be reduced more. In Hobart [CCAMLR headquarters and site of the annual meeting] there was a situation [in 2012] when Russia has offered a slightly different measure of control in this area — to create an area of special scientific interest. But the countries making the proposal on the establishment of marine protected areas would not agree to this. Nevertheless, Russia still does not reject entirely the idea; that is, they do not say that they are against marine protected areas; they are trying to come to a compromise.”

“In 2012 the Russian delegation asked a series of questions in Hobart, and also before. But they have so far gone unanswered.”

Two other Russian organizations concerned with protection of the marine environment, Greenpeace and Bellona, say they have not been following the Antarctic sanctuary debate.

Austral Fisheries is one of the leading catchers of Patagonian toothfish; it does not pursue the Antarctic species, so the Ross Sea MPA would not have an impact on its operations. However, there are already MPA restrictions in force in the toothfish waters it works. Martin Exel is Austral’s general manager for environment and policy. Speaking for himself, not for his company, Exel says: “The Bremerhaven clearly has ramifications for perceptions of CCAMLR’s ability to effectively manage and conserve natural resources around the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions. At this stage, we have seen no indication of changes to those controls, which is reassuring. We’re continuing to work with government, scientists and conservation NGOs to ensure that the differing opinions evident on the value of MPAs, does not spill over to impact negatively the many other management and conservation controls which CCAMLR implements for fisheries and marine living resources.”

Leave a Reply