By John Helmer, Moscow

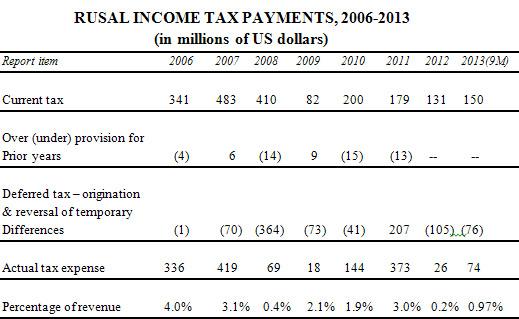

For as long the Russian tax man can remember, Oleg Deripaska has managed to keep his tax bill far below his Russian peers in the metals business. As national champions go, Deripaska is it for tax minimization. In good years or bad years, whether the London Metal Exchange price for aluminium is high or low, Deripaska’s tax has always gone through the floor. In 2003, a federal Tax Ministry report discovered that Rusal was paying income tax at just 2% of revenues. The percentage rose to 4% in 2006, but it has been diving ever since. In 2007, it was 3.1%; in 2008, 0.4%; 2009, 2.1%; 2010, 1.9%; 2011, 3%. Last year his tax rate was 0.2%. This year, according to Rusal’s interim report for the first nine months, tax is running at 0.97%.

How Deripaska has been able to pull off a trick no other major Russian company has managed has been no secret all these years. Three words do the trick – tolling, transfer pricing, offshorization. On December 12, President Vladimir Putin said enough is enough. His offer – either Deripaska brings Rusal onshore and pays Russian tax on his revenue, or else he loses the state banking credits which have kept Rusal from bankruptcy since November 2008. Either way, Deripaska looks washed up.

Here’s what Putin said during his state-of-the-republic address on December 12: “In last year’s Address, I spoke about the challenges in relieving the economy of offshore activity. This is another topic to which I want to draw your attention and which we must return to today.

“Why is that? I will tell you frankly that so far, the results are barely perceptible. Let me remind you about a major transaction that took place this year, worth over $50 billion. The sale of TNK-BP shares occurred outside of Russia’s jurisdiction, although we all know that the sellers were Russian nationals, and the buyer was one of Russia’s largest companies.

“Last year, according to expert assessments, $11 billion worth of Russian goods passed through offshores and partial offshores – that’s 20% of our exports. Half of the $50 billion of Russian investments abroad also went to offshores. These figures represent the withdrawal of capital that should be working in Russia and direct losses to the nation’s budget. Since nothing significant has been achieved in this area this year, I want to make the following suggestions.

“The incomes of companies that are registered in offshore jurisdictions and belong to Russian owners or whose ultimate beneficiaries are Russian nationals must follow Russian tax laws, and tax payments must be made to the Russian budget. We must think through a system for how to collect that money. Such methods exist and there is nothing unusual here. Some countries have already implemented such a system: if you want to use offshores, go ahead, but the money has to come here. It is being implemented in countries with developed market economies, and this approach is working.

“Moreover, companies that are registered in a foreign jurisdiction will not be allowed to make use of government support measures, including Vnesheconombank credits and state guarantees. These companies should also lose the right to fulfil government contracts and contracts for agencies with government participation. In other words, if you want to take advantage of the benefits and support provided by the state and make a profit working in Russia, you must register in the Russian Federation’s jurisdiction.

“We must increase the transparency of our economy. It is imperative to introduce criminal liability for executives who knowingly provide false or incomplete information about the true state of banks, insurance companies, pension funds and other financial institutions.

“We need to maintain our fundamental, firm position on ridding our credit and financial system of various types of money laundering operations. Meanwhile, the interests of honest clients and depositors in problematic banks should be securely protected.

“Today, the fight against the erosion of the tax base and the use of various offshore schemes is a global trend. These issues are widely discussed at the G8 and G20 summits, and Russia will conduct this policy at both an international and national level.”

A week later, on December 19, Rusal responded with a statement for the Moscow business papers. It has a plan, the company says, “for the phased transfer of financial and business operations to the territory of Russia.” Olga Sanarova was the spokesman cited for this claim by RBC, Vedomosti, and Kommersant. Rusal was asked to say when it intends to announce this plan publicly. Elena Morenko for Rusal replied today that the company is making no additional comment on this issue.

One of the press reports claims Rusal has already been obliged by VTB to make concrete commitments to withdraw from its offshore tax schemes in order to continue qualifying for the rollover of state-financed credits. Their exact value is a Rusal secret; they aren’t less than $4.6 billion.

A Rusal insider says that a change in management, not just a change in tax domicile, is now the writing on the wall. “It looks like the top guys are now taking concrete steps to take 100% control over Rusal and Oleg Vladimirovich. These seem to be the right strategical steps before replacing Deripaska.” For more on this reference to Deripaska’s future, see this.

The table following shows the figures Rusal reports for income tax payments over the past eight years. In its reports Rusal acknowledges that what the Russian tax authorities — also the Accounting Chamber — have believed to be an elaborate scheme to understate Russian profits in order to minimize the company’s income tax is lawful, at least until now. The bottom line of the table indicates how low Rusal’s tax has been as a proportion of its revenues.

Source: Company annual reports, Auditor’s Notes, Note 8

In 2003, according to a Tax Ministry analysis commissioned by then Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov, Rusal’s tax proportion is a fraction of that paid by comparable domestic metals producers. The rate paid by Norilsk Nickel, for example, Russia’s leading producer of nickel, copper and platinum group metals, was 19% of revenues in 2003. The 2003 report also identified Severstal, one of Russia’s largest steelmakers, as having paid taxes at between 12% and 14% of revenues. Two other steelmakers, Magnitogorsk and Novolipetsk, were reported as having paid taxes at rates of 12% and 13%, respectively.

In 2012, the comparable tax percentages were 8.3% for Norilsk Nickel; 1.9% for Severstal; and 2.5% for Novolipetsk. Only Magnitogorsk, owned by Victor Rashnikov, paid a smaller proportion of its revenue in tax than Rusal – 0.33%.

At Rusal tax minimization is the handiwork of a former government tax inspector, Vladislav Soloviev. His present title places him immediately below Deripaska as deputy chief executive; he also has a seat on the company board. According to his company biography, before starting as Deripaska’s accountant Soloviev was “Deputy Director of the department of tax policy and worked as adviser to the Minister for taxes of the Russian Federation, where he was responsible for implementing amendments to tax laws.” The bio omits to say when exactly Soloviev stopped advising the tax minister, if stop he did. According to the Finance Ministry, it is currently drafting new legislation to implement Putin’s orders.

At Rusal tax minimization is the handiwork of a former government tax inspector, Vladislav Soloviev. His present title places him immediately below Deripaska as deputy chief executive; he also has a seat on the company board. According to his company biography, before starting as Deripaska’s accountant Soloviev was “Deputy Director of the department of tax policy and worked as adviser to the Minister for taxes of the Russian Federation, where he was responsible for implementing amendments to tax laws.” The bio omits to say when exactly Soloviev stopped advising the tax minister, if stop he did. According to the Finance Ministry, it is currently drafting new legislation to implement Putin’s orders.

Soloviev’s sidekick in implementing Deripaska’s tax strategy is Maxim Sokov, a lawyer by profession after he graduated “with honors from the Russian State Tax Academy under the Russian Ministry of Taxes, in 2000.” Sokov’s current title is director for management of strategic investments. For the time being, the tax lawyer seems to be worth more to Rusal than the accountant – Sokov was paid $8.3 million in 2012; Soloviev $6.4 million.

Soloviev’s sidekick in implementing Deripaska’s tax strategy is Maxim Sokov, a lawyer by profession after he graduated “with honors from the Russian State Tax Academy under the Russian Ministry of Taxes, in 2000.” Sokov’s current title is director for management of strategic investments. For the time being, the tax lawyer seems to be worth more to Rusal than the accountant – Sokov was paid $8.3 million in 2012; Soloviev $6.4 million.

In its last annual report, Rusal said its tax for 2012 had dropped from $373 million in 2011 to just $26 million, but warnings Soloviev and Sokov gave Deripaska and the Rusal board indicated they might not be able to hold down the tax line for much longer. “The Group benefits significantly from its low effective tax rate,” the financial report says, “and changes to the Group’s tax position may increase the Group’s tax liability and affect its cost structure.”

The admitted risk was in the new transfer pricing rules of the Finance Ministry. “New transfer pricing legislation was introduced in Russia from 1 January 2012 which applies to crossborder transactions between the Group companies in and out of Russia and to certain domestic related parties’ transactions in Russia exceeding a certain annual threshold (RUB3 billion [$97 million] in 2012 to be reduced threefold by 2014). The new legislation brings local transfer pricing rules closer to the OECD guidelines, however creates additional immediate uncertainty in their application and interpretation. Since there is no practice of applying the new rules by the Russian tax authorities and the pre-existing practice and caselaw is of little reliance, it is difficult to predict the effect, if any, of the new transfer pricing rules the consolidated financial statements. The Company nevertheless believes it is compliant with the new rules as it has historically applied the OECD-based transfer pricing principles to the relevant transactions in Russia.” (See page 48.)

Rusal reports income tax at Note 8 of its annual financial reports. In the annual report for 2010 the Note commences with this line: “Pursuant to the rules and regulations of Jersey, the Company is subject to income tax in Jersey at an applicable tax rate of 0%.” (Page 138.) The year before, 2009, and in the prospectus for Rusal’s initial public offering ( IPO) covering the years 2006 through 2008, the opening line was more fulsome: “Pursuant to the rules and regulations of Jersey, the Company is not subject to any income tax in Jersey. The Company’s applicable tax rate is 0%.” (2009 Report, page 163.)

Deripaska, Soloviev and Sokov decided to omit this line in the reports for 2011, 2012 and 2013. In these reports Note 8 now commences: “The Company is a tax resident of Cyprus with applicable corporate tax rate of 10%. Subsidiaries pay income taxes in accordance with the legislative requirements of their respective tax jurisdictions. For subsidiaries domiciled in Russia, the applicable tax rate is 20%; in Ukraine of 21% (year ended 31 December 2011 – 23%); Guinea of 0%; China of 25%; Kazakhstan of 20%; Australia of 30.0%; Jamaica of 33.3%; Ireland of 12.5%; Sweden of 26.3% and Italy of 31.4%. For the Group’s subsidiaries domiciled in Switzerland the applicable tax rate for the period is the corporate income tax rate in the Canton of Zug, Switzerland, which may vary depending on the subsidiary’s tax status. The rate consists of a federal income tax and a cantonal/communal income and capital taxes. The latter includes a base rate and a multiplier, which may change from year to year. Applicable income tax rates for 2012 are 9.39% and 15.11% for different subsidiaries (31 December 2011: 9.4% and 15.4%). For the Group’s significant trading companies, the applicable tax rate is 0%. The applicable tax rates for the period ended 31 December 2012 were the same as for the period ended 31 December 2011 except as noted above.”

Just how risky the tax minimization schemes were already, before Putin ordered Rusal to give up tax domicile in Jersey, Zug, and Cyprus, is a point the financial report for 2012 was obliged to acknowledge, even though it dismissed the probability of enforcement. “There are certain tax positions taken by the Group [Rusal] where it is reasonably possible (though less than 50% likely) that additional tax may be payable upon examination by the tax authorities or in connection with ongoing disputes with tax authorities. The Group’s best estimate of the aggregate maximum of additional amounts that it is reasonably possible may become payable if these tax positions were not sustained at 31 December 2012 and 2011 is USD409 million and USD278 million, respectively.”

The potential tax liability for last year is fifteen times the amount of tax Rusal actually paid. With the company running losses of $337 million in 2012, and $611 million to September 30 of this year, the new plan Deripaska is negotiating with Putin must call for an amnesty on tax recovery for the prior years. Otherwise, Rusal is insolvent, and its banks will call in all $9.7 billion of the Group’s accumulated liabilities.

In retrospect, this claim in the 2012 financial report was wishful thinking: “The Group’s major trading companies are incorporated in low tax jurisdictions outside Russia and a significant portion of the Group’s profit is realised by these companies. Management believes that these trading companies are not subject to taxes outside their countries of incorporation and that the commercial terms of transactions between them and other Group companies are acceptable to the relevant tax authorities.”

The prospectus for Rusal’s IPO, released on December 31, 2009, revealed that there was more to minimizing tax than domicile in “tax-efficient jurisdictions”. Tolling contracts between the Russian smelters and the offshore trading units were also part of the tax plan, because they left very much smaller taxable profits inside Russian than ought to have been the case, since Rusal controlled both the onshore and the offshore parties to the contracts. Here’s the fine print at page 29.

“The difference between the statutory tax rate and the Group’s effective tax rate results primarily from the location of Group operations in tax-efficient jurisdictions, including the Group’s trading structure being located in Switzerland as well as the principal trading company being registered in Jersey; and the holding company of the Group, which is also registered in Jersey and holds Group assets through a number of intermediary holding companies registered in Cyprus, Jersey, BVI, Bahamas and other tax-efficient jurisdictions.

“The Group also uses tolling arrangements, mainly because a substantial portion of its alumina is sourced from outside Russia and processed by smelters in Russia, and the majority of third party sales of aluminium are outside Russia. Pursuant to the Group’s international tolling arrangements, a tolling company, registered and subject to taxation in Switzerland and acting upon instructions of theprincipal trading company of the Group, purchases materials, such as alumina, and arranges for their delivery to manufacturers, such as aluminium smelters, in another country for processing into end products, such as primary aluminium, in consideration for a tolling (or processing) fee. The title to the materials or end products is not transferred to the manufacturers and, therefore, where tolling is employed, the shipment of raw materials and end products into and out of the country of the manufacturer is not characterised as an import/export operation and is not subject to local import/export duties. The tolling company and the manufacturer are taxed on their respective profits in their respective countries of tax residence. This tax treatment of tolling arrangements in Russia is subject, among other things, to the requirement that imported materials are processed within a set period of time and, consequently, that finished goods are exported from Russia within that timeframe…

“Tolling arrangements are permitted under Russian law and the Group’s tolling agreements are regularly registered by the Russian customs authorities. The Directors believe that the Group’s tolling arrangements are conducted on appropriate commercial terms based on applicable Russian law and regulation. Processing fees are clearly indicated on the Group’s tax declarations in Russia, and the Russian anti-monopoly authorities also receive periodic reports fromeach of the Group’s smelters on the breakdown of the amount of aluminium that is “produced” versus “processed”.”

“Tolling arrangements are permitted under Russian law and the Group’s tolling agreements are regularly registered by the Russian customs authorities. The Directors believe that the Group’s tolling arrangements are conducted on appropriate commercial terms based on applicable Russian law and regulation. Processing fees are clearly indicated on the Group’s tax declarations in Russia, and the Russian anti-monopoly authorities also receive periodic reports fromeach of the Group’s smelters on the breakdown of the amount of aluminium that is “produced” versus “processed”.”

According to Putin this month, “ if you want to take advantage of the benefits and support provided by the state and make a profit working in Russia, you must register in the Russian Federation’s jurisdiction.” If Putin was talking to Deripaska, as Rusal appears to be acknowledging, then neither transfer pricing nor tolling can be used to reduce Rusal’s tax in future. Until now Rusal’s financial reports claim: “it is not possible to quantify the financial exposure resulting from this risk.”

Leave a Reply