by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

The Wiltshire Police and Police Commissioner Angus Macpherson have revealed new lawlessness in their investigation of the poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury on March 4, 2018.

Police Commissioner Macpherson has overseen the county-wide investigations of the Skripal case and the subsequent case of Dawn Sturgess and Charles Rowley from the beginning. Follow what he has said and done here.

Early this month Macpherson (right) was asked to clarify contradictory accounts he, the local police, the London police, and MI6 through Mark Urban, a BBC reporter, have given in public about what has become of Skripal’s home. At 47 Christie Miller Road, Salisbury, the house was attacked with chemical warfare agent Novichok at the front-door handle, according to the British Government allegations. The culprits were alleged to be two Russian assassins, agents of the military intelligence agency in Moscow, GRU.

“We can confirm”, Macpherson said a year ago through a spokesman, “that police attended Christie Miller Road in Salisbury on the evening of 4 March 2018 as part of our early enquiries into the incident…I can’t confirm how many officers attended, nor how long they stayed at the address.”

In October 2018, Urban reported that three police, led by Detective Sergeant Nicholas Bailey, tried the front door, and then went around the house to get in through the back door. In November 2018 Bailey told another BBC reporter that he and the other police went in the front door. In September 2019 Urban changed his story to the front door.

None of these accounts reported what legal authority the police had for their entry and search. Since Skripal was reportedly comatose in Salisbury District Hospital at the time, he was in no position to give his consent. But British law was protecting him and his property rights just the same. At least, that’s what the Protection of Freedoms Act of 2012 promises British citizens, and requires the British police to protect. That’s the current statute implementing the 17th Common Law principle that an Englishman’s home is his castle. It subsequently became the protection of individual privacy against “unreasonable searches and seizures” in the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution; for that story, read this.

Skripal’s home address was identified within minutes of his collapse by police looking into his wallet and finding his driver’s licence. Police and witnesses at Skripal’s collapse, and later Urban, all confirm this. The police radioed the information to their headquarters commanders who telephoned MI6; MI6 told Urban what happened, and he has printed what he was told. A police van was sent immediately to the address and mounted guard. Read more.

Left: the Skripal house under police guard on the evening of March 4, 2018; Right: the house on April 23, 2019.

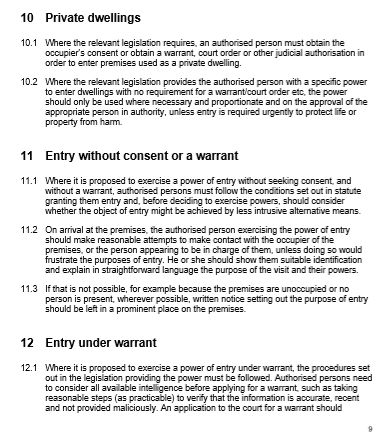

Macpherson and his Wiltshire Police officers knew that if they wanted to get inside Skripal’s house, they had to comply with several statutes, including the Protection of Freedoms Act. They also knew they were required to follow the rules of entry issued by the Home Office to implement the law. The rules are titled “Code of Practice, Powers of Entry”, and dated December 2014; read them here.

Source: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/

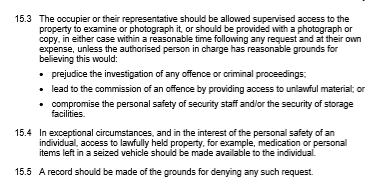

The police were also required to follow strict rules covering the property they took from the house; that included the doors and door-handles. This was all Skripal’s property. The Home Office rules allow it to be retained for police investigations, for evidence in court proceedings, or for destruction. But in all cases, the legal requirement is this:

Source: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/

From the beginning of the Skripal case, British politicians from the prime minister down, and the commercial and state British media without exception, have announced their allegations without following the law on evidence, the law on coroner’s inquests, the law on habeas corpus protecting the Skripals’ rights to be heard themselves, and the law on consular access allowing the Russian Embassy to verify the condition of the Skripals in person. The archive of these lawless actions is a long one; click to open.

For a thorough independent investigation of each allegation and piece of evidence, read Rob Slane’s essays and The Blogmire archive.

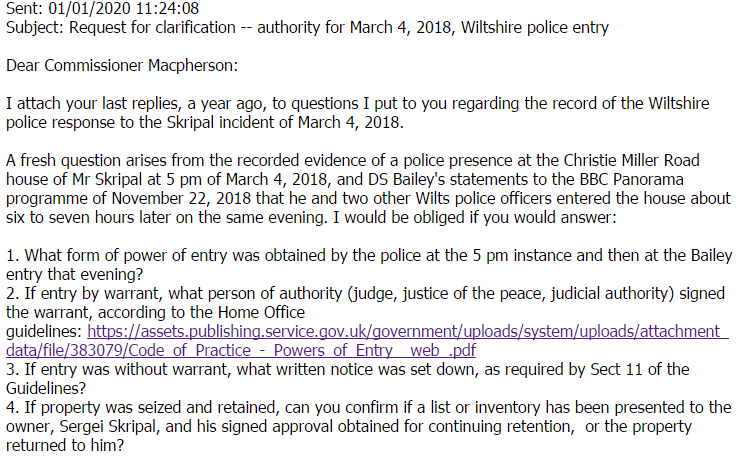

Like the want of the nail in the proverbial horseshoe, the chain of lawlessness began from tiny details. Early this month Commissioner Macpherson was asked what he and his men had done at the beginning, not only to see if it was lawful, but to clarify whether the evidence gathered would be admissible in a criminal prosecution. They were also asked questions to see if they were protecting Skripal, the alleged target of a state crime that has shaken the world — or something quite different.

Here are the questions for Macpherson:

Macpherson would not answer himself, citing the Freedom of Information Act. He referred the questions to the Force Disclosure Unit of the Wiltshire Police. On January 28, they replied:

Substantive answers to each of the first three questions have been refused by the police, with Freedom of Information Act exemptions given as the legal justification.

The Wiltshire Police will not say what legal authority they had, if any, to enter the Skripal house. “To disclose either the methods Wiltshire Police adopt for Powers of Entry or the issuance of warrants (where necessary) would compromise the effectiveness of any future criminal investigations involved with this case. This would also be the case regarding any ongoing or future investigations and operations of a similar nature. For example, if this information were in the public domain, this and any other investigations would be seriously undermined, with disclosure identifying the investigative capability and strategies of the police.”

“This in turn would compromise Wiltshire police’s ability to carry out its core duties and it would also affect the ability of our partner agencies to engage with Wiltshire Police in confidence. In addition to this, disclosure would likely affect the confidence of members of the public to report matters to the police and to willingly engage in investigations if it were believed that such information would be readily disclosed into the public domain.”

The method the police used to open Skripal’s doors is the nail in the horseshoe of the entire assassination affair, and of the warrant for the arrest of the Russians accused. That’s because it was the door-handle on which the Novichok nerve agent was sprayed, according to the investigation which the Crown Prosecution Service announced it had completed in September 2018.

However, Questions 1,2 and 3 to Macpherson didn’t ask about method. They asked for the legal authority for opening the door. The police answer evades these questions. This means that Macpherson and the Wiltshire constabulary are concealing whether they acted legally or not when they entered the Skripal house. If there is no warrant according to the law, and no lawful authorization for entry, then the evidence gathered at the scene is legally inadmissible in a British court of law. That includes the door-handle.

The official narrative of the Russian crime hangs on a warrant or a police entry authorization which is being concealed to this day, and may not exist. And if that doesn’t exist, what does?

The fourth question about Skripal’s property has been asked because MI6 and Urban have made a fuss about a souvenir which Skripal kept on the shelf in his living-room. It was a Ye Olde Cottage, a piece of chinaware which Skripal’s MI6 handler, Pablo Miller, had given Skripal when he was first recruited to spy for MI6 against his own agency, GRU. The provenance of the MI6 gift is not known. The souvenir is a common, inexpensive item.

Price Brothers cottageware of the 1940s -- tea set with salt, pepper, butter and honey pieces with lids, currently for sale by Ellen Sea Art of Columbus, Ohio,for an all-inclusive price of $59.65.

Urban concluded the first edition of his book “The Skripal Files”, issued in October 2018, with his personal viewing of the object inside Skripal’s living-room; that was a few weeks after the attack — despite the Novichok threat and without Skripal’s permission.

“On a shelf in the living room,” Urban wrote, “the little model cottage that Richard Bagnall [MI6 agent Pablo Miller] gave to Sergei back in 1996 still sits. Even after everything, it carries its promise of a better future, a happier one in that mythical place where a man’s home is his castle. This English Eden is a vivid, imagined world, where an old colonel might while away the days of his autumn, relishing happy memories of Kaliningrad, Fergana, or Malta, free from the ugly brutality of those who rule his mother country.”

How Urban survived uncontaminated by the Novichok attack on Skripal’s English Eden, was not explained when, in the second edition of his book issued a year later in September 2019, Urban reported: “In one of the sealed bags transported from Sergei’s home was the little model cottage that Richard Bagnall gave to Sergei back in 1996. Several months after the poisoning a decision was taken that there was no hope of decontaminating all of Sergei’s personal effects. So at an incineration site in southern England, bag after bag were fed into a furnace. The cottage, like so many other tokens of his earlier life, was consumed by fire.”

The horseshoe nail in this story of Ye Olde Cottage is what Skripal knows about his property and has agreed to. After his recovery and release from hospital in May 2018, sometime in the past two years, has Skripal been given an inventory of his personal effects, and has he signed a consent for their retention as evidence by the police, for their return to him, or for their destruction?

These are his rights under the Protection of Freedoms Act, and according to Section 15 of the Powers of Entry rules.

Yesterday Macpherson and the Wiltshire Police replied: “disclosure of Sergei Skripal’s involvement in any continuance of retained evidence in this case would be providing information about the person concerned, thus by virtue of s40 Personal data, any information (if held) would be exempt from disclosure.” Incommunicado since his last telephone call to his family in Yaroslavl on June 26, 2019, his whereabouts unknown, Skripal’s privacy is so strenuously guarded by the British authorities that no one may know whether his property rights are also being guarded for his benefit — or violated for a reason of state.

Leave a Reply