by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

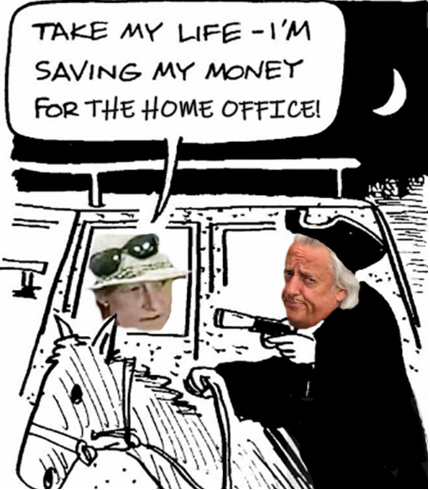

The bid by London lawyer Michael Mansfield (lead image, right) to take a multi-million pound payoff out of the Wiltshire coroner’s inquest into the death of Dawn Sturgess (left), alleged victim of Russian poisoning on July 8, 2018, failed in the High Court on Friday.

A two-judge panel decided that a ruling last December by Senior Coroner David Ridley on the scope of his inquest into Sturgess’s death – allegedly caused by a Russian-made nerve agent called Novichok — was faulty in law, but not in fact or evidence. The judges accepted every allegation about the circumstances of Sturgess’s death by the British Government, repeated by Ridley but so far unattested or cross-examined in either the Wiltshire or London court. In sending the case back to Ridley, the High Court did not direct him to correct mistakes of evidence because none was found.

Mansfield had been hoping the court would order the coroner to broaden his investigation into the Russian state role, exposing thereby what Mansfield claims to have been British Government negligence in protecting Sturgess from the Russian danger.

“Investigating the source of the Novichok,” the court decided, “and whether Messrs Petrov and Boshirov were acting under the direction of others either in London or in Russia, would not be a process designed to lead to a determination of a question which s 10(2)(a) prohibits the inquest from determining… There is acute and obvious public concern not merely at the prima facie evidence that an attempt was made on British soil by Russian agents to assassinate Mr Skripal and that it led to the death of Ms Sturgess, but also at the fact that it involved the use of a prohibited nerve agent exposing the population of Salisbury and Amesbury to lethal risk. There has been, and (to be realistic) there will be, no criminal trial in which the details of how this appalling event came to occur can be publicly examined. We are not saying that the broad discretion given to the Coroner can only be exercised in a way which leads to an inquest or public inquiry as broad and as lengthy as in the Litvinenko case: that is not for a court to say. We can do no more than express our doubts that the remoteness issues raised by the Senior Coroner in paragraph 82 (and referred to in paragraph 85) can properly justify an investigation as narrow as that which he has proposed. Conclusion. We allow the claim on Ground 1 only and dismiss it on Ground 2.”

Contorted by qualifiers and double negatives, the judges — London legal experts believe — have camouflaged their intention in returning the inquest to Ridley to make no practical difference to the outcome, and thereby protect the government from a challenge to the veracity of their Novichok story. Ridley has not been ordered to include in his investigation full disclosure of the CCTV, medical, biochemical and witness evidence; or to call into the Wiltshire court the two obvious witnesses to the alleged use of Novichok, Sergei and Yulia Skripal.

Without the threat these witnesses and their evidence pose to the official narrative of what happened to the Skripals and Sturgess, Mansfield has no bargaining power to negotiate compensation for his clients. Mansfield doesn’t speak to the press except to advertise his claims in the case to the Guardian. That newspaper has not reported Mansfield’s reaction to Friday’s verdict, but conceded he has failed to shake Ridley’s decision to restrict the inquest. “It will be up to him,” the newspaper said, “to look again at the scope of the inquest and decide how to proceed.”

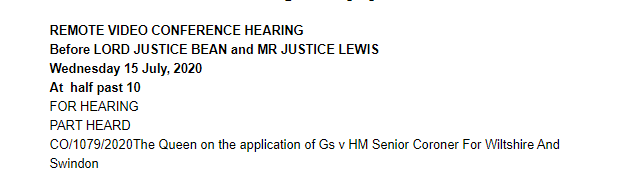

Court of Appeal judge Sir David Bean presided with High Court justice Sir Clive Lewis in a two-day hearing in London on July 14 and 15. Lawyers appeared; no witnesses. The judges’ ruling, issued on Friday morning, can be read in full here.

The Coroner’s ruling of December 20, 2019, which was the focus of the court review, and the analysis of what it means in the story of the Skripal affair, can be read here.

Left to right: Sir David Bean of the Court of Appeal; Sir Clive Lewis of the High Court; Michael Mansfield QC.

Access to the court hearings, which were conducted by remote video livestream, was restricted. Only the Guardian, Salisbury Journal, BBC and Independent had access to the preliminary papers; they refused to say how they got hold of them.

The court posted daily notices of the hearings, and then invited press applications for access to the livestream.

Source: https://www.justice.gov.uk/

When an application was filed, however, the court replied: “We acknowledge receipt of your email. We aim to respond to you in writing, or by telephone, within 5 working days but no later than 10 working days from the date of this acknowledgement.” The 10-day deadline expired after the hearing had concluded and without an answer.

“The use of novichok in Salisbury was the first aggressive use of a nerve agent in Europe since the Second World War,” Mansfield told the High Court in his written submission. Mansfield distributed this document to reporters he expected to be uncritical of his claims and give him maximum publicity. “It put hundreds of members of the British public at risk and killed Ms Sturgess. The issue of who was responsible for it is a matter of almost unparalleled public concern. There is no realistic prospect that the two suspects will face a criminal trial in the UK or that the Russian state will carry out a comprehensive investigation, and no public inquiry into these events has been established. Accordingly, the impact of the senior coroner’s decision is that there will be no further public investigation of these important issues.”

According to the case summary by the two judges, Sergei and Yulia Skripal “were poisoned by Novichok in Salisbury, Wiltshire in England. Novichok is a military-grade nerve agent and there is evidence which indicates that the Novichok may have originated in Russia.” The judges expressed no doubt that “two Russian nationals, Alexander Petrov and Ruslan Boshirov…intelligence officers from the Russian military intelligence service (‘GRU’)…were seeking to kill Mr Skripal”; they had been properly charged with attempted murder, the judges reported.

Bean and Lewis also accepted Coroner Ridley’s ruling of last December that “on 30 June 2018 [Sturgess] had unknowingly sprayed herself with the Novichok, contained in a bottle that she believed to contain perfume. She collapsed and was taken to hospital but never regained consciousness…The post-mortem report concluded that Ms Sturgess had been poisoned by a Novichok nerve-agent. Tests carried out on Mr Rowley, on items at the house where Ms Sturgess collapsed, and on the perfume bottle, revealed the presence of Novichok.”

The British government’s allegation that the Skripal and Sturgess cases were directly connected, and that the weapon in the first was the weapon which killed in the second, must be the truth, Bean and Lewis wrote. “The evidence is that both incidents involved Novichok and the second was a consequence of the first. Indeed, if they were not linked, the case would give rise to even greater public concern than it does already.”

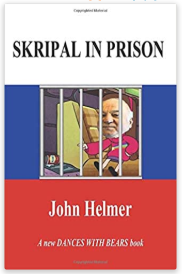

The judges did not doubt the lawfulness or reliability of the evidence for the time, place, and cause of Sturgess’s death, or of the post-mortem, police and laboratory investigations reported by Ridley. None of this evidence has been tested in Ridley’s court yet. For the story of what the evidence fails to show, as well as of evidence tampering by the Porton Down laboratory and the Organisation forthe Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

read the book (right).

The High Court has now accepted the British

government’s story, in order to advise the coroner

on what remains for him to investigate. He decided, say Bean and Lewis, that “the inquest will consider the acts and omissions of the two Russian nationals, Mr Petrov and Mr Boshirov, and whether any act or omission by them or either of them may have caused or contributed to Ms Sturgess’ death. This will include investigating how the Novichok came to Salisbury. He has ruled that he will investigate who was responsible for Ms Sturgess’ death provided that that issue is limited to the acts and omissions of Mr Petrov and Mr Boshirov. He has decided, however, that the inquest will not investigate whether other members of the Russian state were responsible for Ms Sturgess’ death and will not investigate the source of the Novichok that appears to have killed her. It is those two rulings which the Claimant [Mansfield for Sturgess] challenges.”

The High Court has recorded that the Russian soldier assassins, Petrov and Boshirov, “did not appear and were not represented.” The judges didn’t reveal if any attempt was made to contact the two, or serve them with a summons to testify in court. The Russian Embassy spokesman in London, Ilya Erofeyev, said by email: “As the tragic death of Dawn Sturgess has no connection whatsoever to the Russian Federation, no agency of the Russian Government has sought to join the coronial proceedings or to receive the respective papers.”

Source: https://www.rusemb.org.uk/

The Skripals, the two other Russians and the alleged targets of the Petrov and Boshirov, were not called to testify in the High Court. Ridley has also not interviewed them. No explanation for the exclusion of the Skripals’ evidence has been mentioned by the coroner, judges or lawyers so far.

Sir James Eadie QC, representing the Home Office as the branch of government directly engaged in the case, said the High Court should dismiss Mansfield’s bid. “The background to Ms Sturgess’s death is the attempted murder of Sergei and Yulia Skripal,” he said. “Ms Sturgess was not a target of that attempt – she appears to have been the tragic victim of chance, having come into contact on 30 June 2018 with novichok discarded by the attackers.”

Left: Sir James Eadie, advocate for the British government’s case that the package and perfume bottle (right) had been discarded after the attack on the Skripals in Salisury on March 4, 2018, then not discovered by police in Amesbury until July 11, twelve days after Sturgess had allegedly come into contact and was hospitalised, and three days after she had died.

“Sir James argued the coroner was entitled to reach the decisions he had reached regarding the scope of the inquest. Mr Ridley had also made it clear that he was not reaching a final conclusion but would keep the scope of the inquest under review, Sir James added.” In their judgement, Bean and Lewis accepted part of Eadie’s argument that Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, providing for state protection of a citizen’s right to life, did not require the British government to prove their intelligence and security agencies had done enough to secure Sturgess from Russian poison attacks. “We conclude that the Senior Coroner was correct in ruling that the requirements of Article 2 of the Convention did not oblige him to carry out an investigation into the responsibility of Russian agents or the Russian state for the death of Dawn Sturgess.”

But they were uncomfortable, they added, with the narrowness of Eadie’s interpretation of what the coroner might do, and avoid doing, to investigate the circumstances of the Sturgess case. “We asked Sir James whether it would have been a lawful exercise of discretion for the Senior Coroner to rule that the scope of the inquest would be even narrower than is at present proposed, by being limited to the discovery by Mr Rowley of the perfume bottle containing Novichok, its opening and the fatal consequences for Ms Sturgess. Again, Sir James replied that it would.”

“It might seem surprising to members of the public, and certainly to a widow or other bereaved relative,” Bean and Lewis concluded, “to learn that the question of whether the coronial investigation of her husband’s death should be as broad-ranging as Sir Robert Owen’s proved to be [in the Litvinenko case] or as narrow as Sir James submitted it could have been, or somewhere in between, can depend on the largely unreviewable discretion of the individual coroner appointed to hear the case.”

Ridley should not have so much discretion, Bean and Lewis decided. He was told he wasn’t obliged to conduct “an inquest or public inquiry as broad and as lengthy as in the Litvinenko case” so long as he didn’t stick to “an investigation as narrow as that which he has proposed.” He was also told that the next time round he “should be careful… to avoid using inappropriate legal terminology.”

Leave a Reply