By John Helmer, Moscow

When Transcontainer, the state rail company, started selling its shares in the form of global depositary receipts (GDR) on the London Stock Exchange on November 11, the price fixing was $80 per share, $8 per GDR.

“We are very pleased that the first IPO of a subsidiary of Russian Railways has been positively received by international investors’, said RZhD President Vladimir Yakunin (see image). ‘We view this as a strong gesture of their support for the ongoing reform of the Russian railway transportation sector. RZhD warmly welcomes new shareholders of Trans-Container and will continue to support Trans-Container’s business in Russia and abroad.”

But this isn’t what happened at all – and Yakunin, along with everyone else in the international market, knows it.

For the first time since the Hong Kong Stock Exchange listing of Rusal, the aluminium monopoly, on January 27, a state-guaranteed share sale has failed to find market buyers at the price on offer. It is the first attempt by Russian Railways to float shares on the international markets. Coming after Transcontainer in the plan are a 75% stake in Hong Kong-based subsidiary Freight One, valued at $5 billion, and an as yet undecided stake in subsidiary Freight Two in roughly two years’ time. The auspices are not positive.

They belie the claims Prime Minister Vladimir Putin made at a Berlin business forum on the weekend, when he appeared to be blaming a conspiracy against Russian businesses and businessmen for the way in which the capital markets react. After Putin commented positively on cooperation in the railways sector between Germany and Russia “to successfully implement their projects to create new logistical complexes and upgrade the quality of freight handling,” Putin complained that when “Russian capital is trying to enter European business, it is simply denied entry in the European market.”

For examples, Putin mentioned three defeats of Russian oligarchs – Lakshmi Mittal’s over-bid to beat Alexei Mordashov’s offer for steelmaker Arcelor in 2006; General Motors’ rejection of Oleg Deripaska’s offer to buy Opel in 2009; and the refusal of the Hungarian government to allow Surgutneftegaz to exercise its 20% shareholding rights in MOL. For his fourth example, Putin referred to the Swiss government’s prosecution of Victor Vekselberg for share market fraud. But since that has ended recently in the dismissal of the earlier findings and an order for legal costs in compensation, Putin added: “It seems [the problem] is resolved now, thank God. But it’s impossible to work this way!” That is the news agency report of what Putin said. In the prime ministry’s version, the phrase “thank God” has been omitted.

If not for divine intervention, how do markets behave towards Russian sale offers?

Transcontainer has attempted to sell 35% of its 139 million shares. The price it hoped to fetch was between $79 and $89 per share, $7.9 to $8.9 per GDR. Three state nominated buyers agreed to buy at this price. The Far Eastern Shipping Company (Fesco), which is heavily indebted to the state bank VTB, agreed to buy 12.5% of the company’s shares; VTB Capital itself bought 8.75%; and the Blagosostoyanie pension fund, a railways entity, bought 5.2%. If Transcontainer’s own purchases of shares for a scheme of options rewards for management are counted, at least 80% of the IPO was bought by state trustees.

At least one of the foreign shareholders, Moore Capital Management, sold out, and probably another foreign investor, GLG Emerging Markets special situations fund. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) says it has held on to its 9.25%, which it bought at a private placement in 2007.

If the underwriters and book-runners are also holding small blocs of the new shares, was there any significant foreign investment in the IPO? Transcontainer spokesman, Dmitry Yesipov, refuses to say, claiming that the company is observing a 40-day silence period following the IPO. Until the end of December, it will say nothing about the new shareholding, nor comment on the result of the IPO.

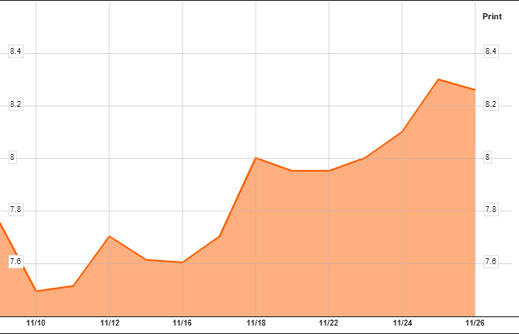

But the stock market continues to talk, indicating that on very small volumes of shares traded, the share value remains uncertain:

In market terms, this outcome looks to be the opposite of Yakunin’s claim. Does that make the IPO a failure? “Not a failure, not a success – something in between”, comments George Ivanin, transportation analyst for Alfa Bank in Moscow. His survey of London investment institutions has uncovered the assessment that there was insufficient demand to support the price which the government had set for Transcontainer’s shares. The reason, according to Ivanin, is that most institutions believe the share price target was too high. Even at the low point of the target range, the market realized that this represented a multiple of 40 times the price/earnings ratio of comparable emerging market transportation companies, which aren’t Russian. Container Corporation of India, for example, trades on a multiple of 20.9 times its price/earnings ratio.

Was there an anti-Russian conspiracy to deny Transcontainer the value it deserved? Or did Transcontainer and RZhD decide not to allow a genuine market sale at all? Or were Fesco, VTB and the railwaymen’s pension fund ordered into the breach when the size of the market failure loomed?

Renaissance Capital has reported to its clients that “this [was] a successful placement for the company, despite significantly higher business risks (exposure to a single, highly cyclical product) and no real track record.”

But Russian Railways has a real track record — and for those who remember, it is one of non-accountability, if not of unremitting corruption. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the establishment of the post-communist Russian state by President Boris Yeltsin and his allies, the state railways remained one of the largest sources of ready cash which continued to come into state coffers. In parallel, rail freight charges and receivables became a form of administrative currency to be used by corrupt officials and their business allies to put pressure on the country’s major enterprises, which depended on the railways for their raw materials and access to markets.

Power over such revenues and obligations, and over schemes to swap enterprise debt for enterprise shares, was shared between the federal railways administration in Moscow (there was a fully autonomous railways ministry at the time), and the regional railways and regional governors.

Yeltsin’s appointee to run the system during his second term (1996-2000) was Nikolai Aksenenko, a career railwayman. In time, Aksenenko not only ran the railways, but he also became Yeltsin’s confidant to run the entire government as first deputy prime minister; as a candidate prime minister in 1999; and then as candidate to succeed Yeltsin as president. In the last years of Yeltsin’s term, Aksenenko was a stumbling block to the growing ambition of Putin, who succeeded in toppling him, becoming prime minister in August 1999, then president on December 31 of that year. Putin’s advancement doomed Aksenenko, and made a reorganization of the railways inevitable.

Aksenenko diverted cash from the railways to benefit Yeltsin, himself, his family, and his allies, notably through offshore schemes like the creation of TransRail, a Swiss-based entity which held a monopoly on international freight and hard currency operations of the Russian system, and retained profits for distribution corruptly.

When Putin took over the presidency, Aksenenko was first removed from the prime ministry, and then – alone among the ministers of state of the Yeltsin period – charged with corruption. The charges were never taken to trial, and Aksenenko was allowed to leave the country for abroad. He died in July of 2005.

Into the management of the railways, Putin put his personal appointee Yakunin. He has supervised the transformation of the ministry-run system into the state shareholding company, and then into a plan of subsidiary divestments and publicly listed spinoffs. The Transcontainer IPO is not the first offshore transaction with state rail assets which Yakunin has directed. There was, for instance, the transfer of the locomotive and rolling-stock construction monopoly to an Amsterdam company controlled by the oligarch, Iskander Makhmudov, in November 2007. But that was a private, a very private transaction.

This month’s Transcontainer IPO is the first public transaction to test the accountability of the Russian railways companies, and of the state guarantee on which their value depends. Thank God.

Leave a Reply