By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

Every summer and winter the London art auction houses display the best of Russian painting and fine art objects for a bidding match between Russian bank robbers on the run; museums; boardrooms; and everybody else with the taste to fit their pockets. When the price of oil goes up, along with the Moscow stock market index, pockets swell and the price of the art goes up. When court arrest warrants and asset freeze orders are pressing the robbers, the price goes down.

All the fine art markets are the same; the wartime prejudice against Russian art inflicts a discount. The Russian supply is more limited on account of the Culture Ministry’s export controls, and also because the supply history is several centuries shorter for Russian paintings than for Chinese and European.

This year the growth in the clean money was expected to offset the absence of the dirty money. Auction house sources also anticipated that more Russian buyers would participate in the internet format this time than last year’s first Covid-19 auction. A well-known London dealer forecast at the start of this month: “The June 2021 Russian Sales are the best yet! Ever! In history! In the whole, wide, beautiful world!” This has turned out to be Ukrainian surrealism.

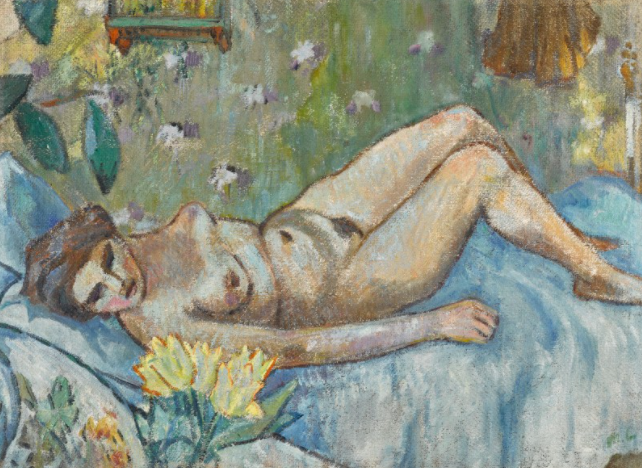

According to last week’s results from Sotheby’s, Christie’s, MacDougall’s, and Bonham’s, the virtual sale totals are significantly better this year than a year ago; they also remain significantly below the last live auction totals in June 2019. On the traditional taste tests for nudes and for scenes of Crimea, this year’s results show reluctance to put the money up. Sotheby’s attempt to sell the combination, “Female Nude in Crimea” (lead image) by Stepan Dudnik, failed to reach the bargain reserve price of £6,000.

Dudnik (1914-1996) started as an orphan and then a construction worker, But he had become a successful Moscow academy painter by the time of the war. He had a talent for breasts, if not for faces, toes and fingers. But Sotheby’s note warns “there are several areas of retouching across the sitter’s face and body”.

For the full sale catalogue from Sotheby’s click to view. The house also provided a short-cut link for viewers who selected the Dudnik nude. They were advised:

The Sotheby’s sale total last week turned out to be £9.7 million; this compares with £5.6 million in June 2020; £12.5 million in 2019. For the full story in 2020, read this; for 2019, click. At this week’s sale, Sotheby’s offered 228 lots; 152 were sold (67%). The clearance rate is unchanged from 2019.

Sotheby’s nude stock started at 9 lots; 4 of them failed to sell. Mikhail Larionov’s “Nude” was painted, not in Crimea but in Odessa in 1902; it failed Dudnik’s breast test (“minor retouchings”) and was no better on fingers and toes. However, it sold for £862,000. This was second best in show, trailing only a sentimental Ukrainian scene – “Moonlight over the Dnieper”, painted by Ivan Aivazovsky in 1858. The painting has been traded in Europe at least twice already this century among European buyers.

Source: https://www.sothebys.com/

According Tatiana Markina in the Moscow Arts Newspaper, this painting has fallen in value by more than a third since it was last auctioned in 2008 at £1.4 million.

Rival London house Christie’s offered 251 lots; sold 171 (68%); and fetched a total of £6.2 million. This compares with £16.2 million in June 2019; £3.3 million in June 2020. The latest result was a significant improvement over a year ago, when the house was criticised for “an incoherent, mish-mash on-line presentation that was impossible to navigate” and lots that were “little more than bric-à-brac”. For comparison with 2019, read this. The archive of London Art Week and Russian culture stories can be followed here. For Simon Hewitt’s report of “one of the strangest [art markets] in the world”, click to read.

On the Russian taste for sex, Christie’s has proved to be more prudish than Sotheby’s. The house catalogue omits those lots which failed to sell, and can be viewed here. The list of resulting sales can be read here.

One of the three nudes Christie’s offered managed to sell – that was Grigory Gluckmann’s “Women in a Landscape” which has been in the US since Gluckman emigrated there in 1941. Its technical execution is inferior to Dudnik. Sale price was £9,375. A second naked Gluckmann failed to attract a buyer.

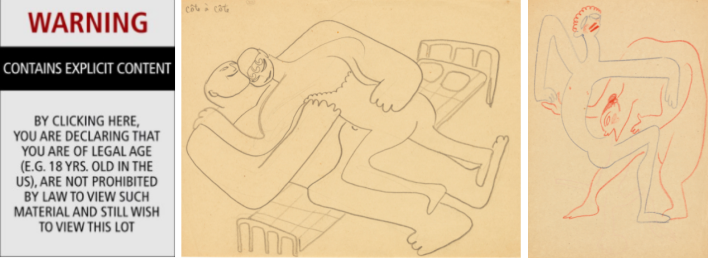

Then there were the erotic drawings of Sergei Eisenstein – a little known artwork by one of the most famous Soviet film directors. Russian art market sources say they were unaware of their existence until now. Christie’s displayed them with a catalogue warning against adolescent prurience.

Lot 64, originally displayed at this link but that has now disappeared. Christie’s estimated that the series of drawings would fetch between £7,000 and £9,000. Some of the present drawings were inscribed ‘AA’, which stood for Alma-Ata, the former name of the city in Kazakhstan to which Eisenstein was evacuated with his film production company between 1941 and 1946. Andrei Moskvin (1901-1961), a well-known cameraman, worked with Eisenstein there. According to Christie’s, Moskvin subsequently received a collection of Eisenstein’s drawings, some of which appeared for sale this month.

A source at Christie’s confirms the Eisenstein series was “unsold not withdrawn.”

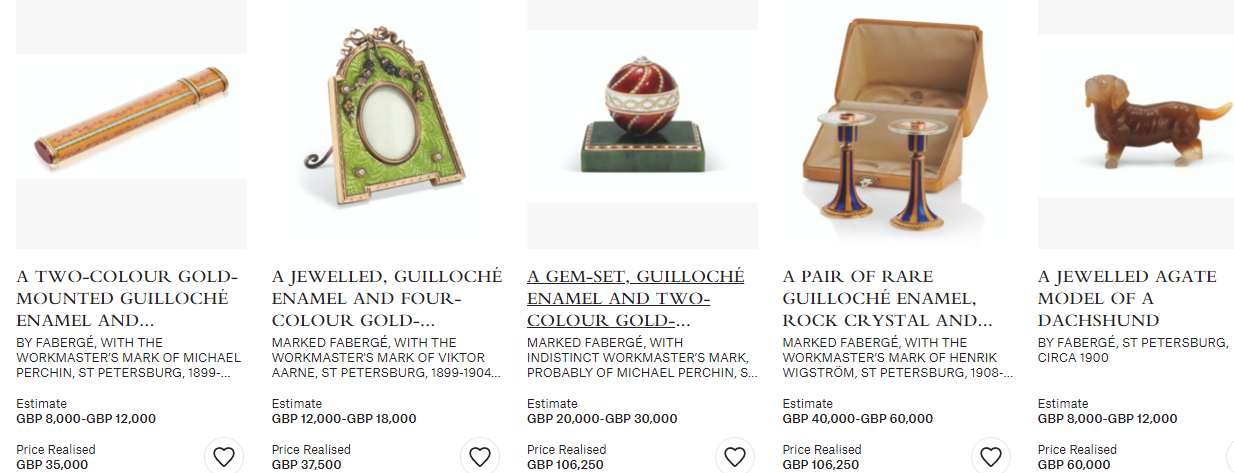

There are no warnings against mature-age vulgarity in the Christie’s catalogue. Indeed, the successful sale of these Fabergé pieces, at double and triple their estimated price range, depended upon it:

Source: https://www.christies.com/ -- lots 101-105.

Bonham’s continues to slip behind the other London auction houses, heading for bargain basement status. Its sales totaled £1.2 million, behind the 2019 total of £1.9 million. Bonham’s officials decided against holding an internet auction last June. Just two canvases, a still life by David Burliuk (1882-1967) and another by Nikolai Kuznetsov (1850-1929), accounted for more than half the value of all the paintings in Bonham’s sale last week; 40% if the icons, jewellery and table objects are included. Of the 167 lots offered, just 92 (55%) were sold; the stock clearance rate was 52% in 2019. Sellers of Russian art can see their chances are decidedly better elsewhere; investors especially.

Left, David Burliuk, “Morning Still Life” (about 1920) -- £250,250. Right, Nikolai Kuznetsov, “Still Life with apples and an orange tree” (1921) – £212,750. Both paintings remain in Russia; the Kuznetsov is not allowed for export; it is unclear what the status is of the Burliuk. Source: https://www.bonhams.com/

At its June 10 auction MacDougall’s has reported total sales of £4.4 million, more than double last year’s total; the result comes much closer to the £5.4 million achieved in 2019 than the rival auction houses. The result is also a jump in MacDougall’s market share from 15% in 2019 to 21% now. Christie’s has been the biggest loser this month; its market share of 45% in 2019 has dwindled to 29%.

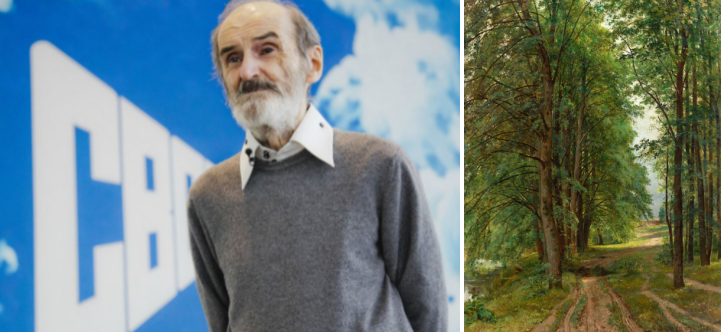

MacDougall’s offered 223 lots; 121 (54%) were sold. Just five lots accounted for £2.2 million, half the total value of the pictures sold. The top scorer was a new work by Eric Bulatov, titled “The Vault of Heaven”, which he painted in 2007; it has fetched £645,000. After Bulatov came another of Ivan Shishkin’s late-19th century portraits of trees; it sold for £508,000. This one was bought and taken out by a Brazilian ambassador to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, then sold to another foreigner in 1988.

Left: Eric Bulatov with his “Vault of Heaven” photographed by the Yeltsin Centre ; right, Ivan Shishkin, “Forest Road” (1896). Source: https://macdougallauction.

MacDougall’s catalogue offered three nudes; one picture of Crimea. Two of the nudes sold, but the third and “Crimean Village” by Alexander Glouschenko (about 1970) did not. For the first time in many years, MacDougall’s failed to sell a work by the most over-rated Russian painter of the first half of the 20th century, Nicholas Roerich. A canvas of his from 1919, titled “Clouds” and owned in the US, failed to draw a buyer at a reserve price of £60,000.

When libido and patriotism are flagging as drivers of demand and prices at the London Russian Art Week, there will always be oil and the Moscow Exchange (MOEX). The Russian art department executives at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonham’s are even more prudish about them. They are reluctant to answer questions about how they see demand for Russian paintings is changing between Russians in Russia and foreigners or Russians offshore.

CRUDE OIL PRICE (BRENT), ONE-YEAR PRICE TRAJECTORY

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/

MOSCOW EXCHANGE (MOEX), ONE-YEAR TRAJECTORY OF THE PRICE INDEX

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/

Apart from Hewitt in Russian Art+Culture, there is a lack of published charting and indexing in the London market. In the domestic art market, however, Art Investment.ru keeps close tabs.

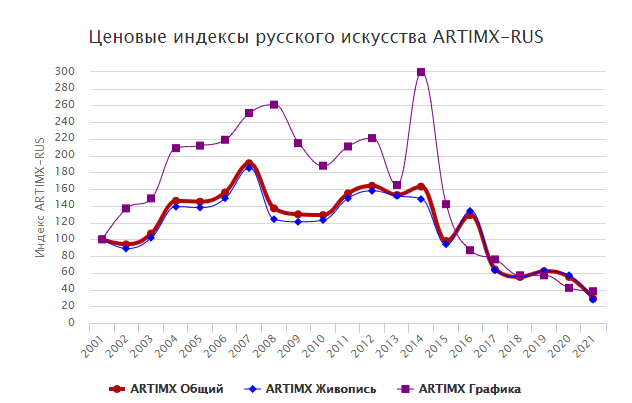

THE ART INVESTMENT INDEX (ARTIMX), RUSSIAN ART PRICE TRAJECTORY

Source: https://artinvestment.ru/

KEY: red=all; blue=paintings; black=graphics.

The chart shows that the domestic market peaked in 2008, and that despite two points of revival in the first war year of 2014 and then again in 2016, the overall price continues to decline. Why is this trend going downwards when the London market appears to be going up, at least until recently?

Denis Lukashin is a leading Moscow art expert and co-owner of Art Consulting, which advises Russian buyers on authentication of works and market pricing trends for individual artists. He says: “The situation is complicated. Our art market, as you remember, is closed for foreign buyers. They can buy Russian art, but they can’t take it abroad, out of Russia. The supply of art in Russia is still very high, and the demand is usually for the low and medium-price segments ($25 to $10,000). The pandemic has developed online auctions, but also in these market segments. But the demand in Russia isn’t enough to raise the prices. The demand from investors for really unique and expensive pieces of Russian art is also very low. This is why oil and MOEX have a very low influence on Russian art sales.”

“The situation is reversed in London. The London market shows a high demand and low supply, because Russian art there is concentrated mostly in private collections. Each year they are rare guests at the London auction houses.”

Konstantin Baburin of ARTInvestment agrees with Lukashin that the ARTIMX index reflects the domestic market where supply is “overflowing and the works are banned from export abroad.”

According to William MacDougall of the eponymous London house, “there is some divergence [between the domestic and London markets] due to Russian export controls and other factors, but that’s limited because the majority of buyers at the London auctions live in Moscow and British export controls on Russian art are pretty liberal.” Ahead of this week’s sales, MacDougall was predicting recovery in demand and prices. “Our own private sales suggest that the market is up this year, and that estimates will be exceeded when the hammer comes down. Oil prices are up and the general global economic environment is improving.”

Left to right: Simon Hewitt, Denis Lukashin; William MacDougall.

Yekaterina Trofimova, an art investment specialist in a Moscow accounting firm, comments that “we have not learned how to monetize the art market. Of course, Russia has something to show, including for western collectors, gallery owners, and investors. We have a great legacy, but it is poorly monetized. We are definitely moving from the usual market of raw materials to the creative industries. But managing the art market as a full-fledged business is something in which the cultural capitals of Russia still lose out on the international stage. The presence of private galleries, auction houses and venues for international exhibitions is one of the important criteria that can help establish the status of the art capital.”

“The assessment of the scale of the market and its accuracy is influenced by the shadow market, which is simply huge in the creative sphere. Moreover, the shadow and even black markets for art objects are flourishing not only in developing countries, such as Russia, but also in developed economies. We are talking about the turnover of art objects between the seller and the buyer without the participation of the state — without official registration of the transaction. Measurements here are quite difficult to conduct.”

Asked which segments of the Russian art market are more or less legalized, Trofimova said: “Legalized antiques, for example. Icons are protected by law; they are difficult to export abroad illegally. But in the case of objects of contemporary art, there are more opportunities for ‘informal turnover’. The art industry is not just about paintings and sculptures, but it is a broader concept. It includes the entire entertainment industry — including tourism, which helps to make money on creativity.”

“Our investment culture is not very developed yet. The fact is that in Russia there is a sacred attitude to art. Investing in art objects is considered not a very good thing and certainly unusual, something outside the life of an ordinary person. But this situation will change quickly. Art events are growing and multiplying, the number of exhibitions and biennales is increasing.”

Leave a Reply