By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

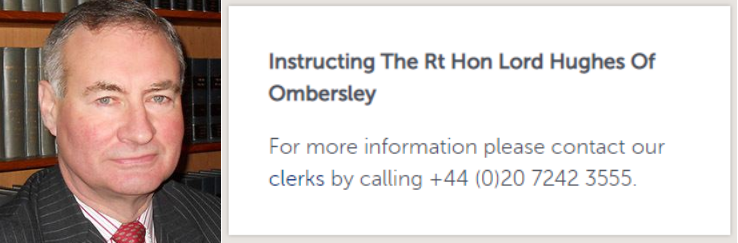

A new judge has been appointed out of retirement by the British Government to run a public inquiry into the cause of death of Dawn Sturgess in July 2018. He is Anthony Hughes, Lord Hughes of Ombersley, 73, who retired as a judge of the Supreme Court, the highest of the British courts, in 2018. A specialist in criminal law, he was a Court of Appeal judge between 2006 and 2013, and a High Court judge from 1997 to 2003.

The Hughes appointment was announced in the House of Commons on Thursday.

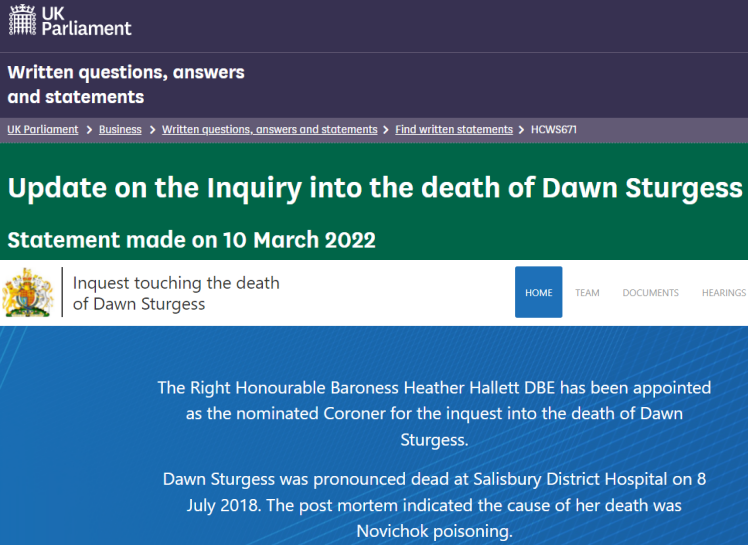

The cause of Sturgess’s death was declared by British government officials before the medical evidence and witnesses had been examined and tested in court and in public. The government has published its conclusion on the website of the Sturgess inquest. “Dawn Sturgess was pronounced dead at Salisbury District Hospital on 8 July 2018. The post mortem indicated the cause of her death was Novichok poisoning.”

This allegation has been part of the government’s narrative that the Russian-made nerve agent Novichok was brought to London, and then to Salisbury, by two Russian soldier assassins as part of a plot ordered by the Kremlin to kill double agent, Sergei Skripal. The attack on him on March 4, 2018, failed.

Skripal, as well as his daughter Yulia Skripal, survived, although not to tell the tale.

For four years now they have been held incommunicado by the British secret services; they may be imprisoned; they may be dead. They have been excluded from giving any evidence in court on what happened to them. They have been prevented from contacting their family in Russia, and speaking in public and to the press.

Hughes’s appointment this week follows the controversial and unexplained replacements of two coroners investigating the chain of Novichok allegations leading to Sturgess’s death. Hughes himself was not picked for the post for several months.

With an unusually modest public career record and no media reporting of his judgements over his 21-year career on the bench, Hughes appears to be about as obscure a figure as the government could have found.

However, the archive of his Court of Appeal judgements reveals that Hughes is a stickler for the criminal law rules on the inadmissibility of tainted and hearsay evidence, and on rejecting faulty directions by judges to juries before their verdicts. Whether Hughes has been selected for the Novichok job because officials believe he can be counted on to stick to the official narrative, or whether his record for quashing unsafe convictions will prevail this time round is about to be tested.

Announcing the appointment in the House of Commons on March 10, the Home Secretary Priti Patel said next to nothing about Hughes — and everything she expects Hughes to decide when he concludes his investigation in two to three years’ time.

“I announced on 18 November 2021 of [sic] the Government’s decision to establish an Inquiry under the Inquiries Act 2005, to investigate the death of Dawn Sturgess in Amesbury on 8 July 2018, after she was exposed to the nerve agent Novichok. The Inquiry will now be chaired by the Lord Hughes of Ombersley. Lord Hughes is a retired judge who was a former Judge of the Supreme Court, as well as a Lord Justice of Appeal and Vice President of the Criminal Division. Lord Hughes is also a judicial commissioner to the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office (IPCO).”

IPCO was started in 2017 and is paid for by the Home Secretary; its commissioners conduct annual inspections of the operations of the police, security and intelligence services, including the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). In IPCO’s report to the Prime Minister for 2018, the year of the alleged Novichok attacks, the commissioners said: “Overall, we were impressed with the rigorous way SIS makes judgements about risk in this context: every officer we spoke to clearly demonstrated a strong grip on compliance and legal issues which are evidently treated as a core part of SIS’s everyday work …We reviewed a number of specific [MI6] submissions covering potentially high-risk cases. We were pleased that these included a strong necessity and proportionality argument for running the case in question, along with robust processes for keeping the risks involved under constant review.”

Source: https://ipco-wpmedia-prod-s3

The Sturgess inquest website operated by Hughes’s predecessor, retired Appeal Court judge Baroness Heather Hallett, has not yet caught up with the replacement of Hallett by Hughes. It continues to repeat the conclusion Hallett was expected to reach at the end of her investigation.

Source: https://dawnsturgessinquest.org.uk/

In their retirement from the bench, both Hallett and Hughes have been running personal consultancy businesses. Hallett is also on salary from the secret services.

Hughes is listed as a consultant at the 7BR barrister chambers in London; the name reflects the office address at 7 Bedford Row. The law firm advertises its expertise in inquests and public inquiries. “7BR’s Inquests & Inquiries barristers provide expert representation to bereaved families, and public and private clients across a wide range of cases. 7BR’s multi-disciplinary approach is a key asset in this area, which can cut across a number of traditional practice areas including criminal law, clinical negligence and personal injury, health and safety and regulatory, family law, and public law.” None of the government-ordered inquiries listed have engaged Hughes.

Anthony Hughes and his business card at the 7BR Chambers. Hughes’s profile on Wikipedia is brief. For a videoclip of a speech he gave in 2019 on human rights in the criminal law, click to watch.

A search of British press coverage of Hughes’s career found a single BBC reference when he was one of the panel of Supreme Court judges which in 2017 ruled unanimously against Prime Minister Boris Johnson during his attempt to suspend parliament in the Brexit debate. According to the BBC, Hughes’s hobbies were “garden labouring, mechanics and bellringing”.

A search of Hughes’s appeal court record reveals his participation in 395 cases over seven years.

In 2007, for example, Hughes wrote the judgement for a panel of three judges who quashed murder convictions for three defendants because the evidence included against them was hearsay and should not have been admitted by the trial judge. “There was, no doubt, a powerful case against each of these defendants in their different ways. It is a case which any jury might have accepted whether this evidence was admitted or not. It is, however, quite impossible to say whether in the end these defendants or any one of them was convicted as a principal or as a secondary party. It is impossible to say what impact the evidence of what Harris said about who had the knife would have had, had it been given. We have reached the conclusion that it is simply impossible to say that these convictions, and it is true of all three defendants, can be said to be safe.”

The same year Hughes ordered that a conviction for robbery should be quashed because inadmissible evidence had prejudiced the defendant. “The defence, in reality, did not realistically have any chance of giving evidence about the girl’s motive. Secondly, the judge, though he may have intended in due course to administer strict warnings to the jury about the difficulties faced by a defendant who could not test the out-of-court statement of the girl, did not in fact ever do so. In those circumstances this evidence could not properly be admitted under section 114 either. We accordingly come to the conclusion that this important evidence was wrongly admitted before the jury and for those reasons this conviction must be quashed.”

In 2009 Hughes ruled to overturn a conviction for burglary because the jury “was infected by information damaging to the defendant which was not part of the evidence.” “In all those circumstances we are persuaded that in the present case it is impossible not to fear that the jury has been infected by material which it ought not to have had.”

For a detailed analysis of the improbability and inadmissibility of the British government’s evidence in the Skripal case, read the book.

For the inadmissibility of the medical

evidence in the post-mortems conducted

after Sturgess’s death, read this.

Leave a Reply