By John Helmer, Moscow

By releasing on bail all but one of thirty Greenpeace protesters charged for an attack on the offshore Russian oil platform Prirazlomnaya in September, Russian prosecutors and a St. Petersburg court have pre-empted and defeated Greenpeace and the Dutch Government.

Greenpeace and the Dutch had applied for “provisional measures” from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in Hamburg. Their demand was for the release from arrest and prison, and for permission to leave Russia altogether, for the 30 protesters, including three of them who are Russian citizens. The demand also included the release of the Arctic Sunrise, the converted icebreaker which Greenpeace has been operating this year in the Barents Sea and Pechora Sea, above the Arctic Circle. The Russian government has preempted the vessel release by issuing guarantees of the state icebreaker fleet company which owns the berth at which the Arctic Sunrise is moored; and of the Coast Guard division of the Federal Security Service (FSB), which is guarding it.

A hearing on the claim was held in Hamburg on November 6. The story can be read here. The tribunal then issued its 25-page ruling on November 22. The full text can be read here. Of the 21 judges on the ITLOS bench who heard the case, 19 voted in favour of the measures applied for on condition the Dutch government posted with a Russian bank a bond of €3.6 million. Six judges differed with the text of the ruling; four of them voted in favour of the order but differed substantially with the majority opinion.

Two judges voted against, filing dissenting opinions. They are the Russian judge Vladimir Golitsyn (left) and the Ukrainian judge, Markiyan Kulyk (right). Golitsyn,66, has been a university professor of law in Moscow, and on the ITLOS bench for five years. He is also president of the Seabed Disputes chamber at ITLOS. Kulyk, 43, trained as a lawyer and has served as a Ukrainian diplomat in Kiev, at the UN, and at the rank of ambassador.

Two judges voted against, filing dissenting opinions. They are the Russian judge Vladimir Golitsyn (left) and the Ukrainian judge, Markiyan Kulyk (right). Golitsyn,66, has been a university professor of law in Moscow, and on the ITLOS bench for five years. He is also president of the Seabed Disputes chamber at ITLOS. Kulyk, 43, trained as a lawyer and has served as a Ukrainian diplomat in Kiev, at the UN, and at the rank of ambassador.

The Russian Foreign Ministry has dismissed the ruling. It argues that ITLOS lacked jurisdiction to consider the facts of the case, make judgements on what had happened, or override Russian sovereignty over the rig and its attackers. The Ministry also says it refused to participate in the tribunal proceedings because it does “not consider the situation as a dispute between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Russian Federation concerning the rights and obligations of the Russian Federation as a coastal state in its exclusive economic zone.”

By last Friday, however, Greenpeace has paid Rb2 million ($62,500) in bail money for each of the 29 releases, and agreed that its members will appear for their trial on charges of disorderly conduct; the trial has been scheduled for February. The Arctic Sunrise must also remain where it is moored at a pier in Murmansk harbour. Total bail paid by Greenpeace so far is the equivalent of $1.8 million.

One Greenpeace member, Colin Russell, the radio operator on board the Arctic Sunrise, remains in jail, his bail application denied. Exactly why his case has been treated differently by the Russian prosecutors, and why the Australian government has failed to negotiate for his bail, Greenpeace isn’t saying. Paul Myler, the Australian ambassador in Moscow, has claimed the Russians had made “an administrative error [which] would be rectified.”

The Russian Foreign Ministry has indicated that Russell’s role as the radio operator was instrumental in communicating Greenpeace orders from outside Russia, and from the Arctic Sunrise to those aboard the speedboats attempting to board and take control of the oil rig. According to the Foreign Ministry’s release of November 22, “there is reason to believe that the management actions of persons trying to enter the platform was carried out directly from the vessel using radio communications.”

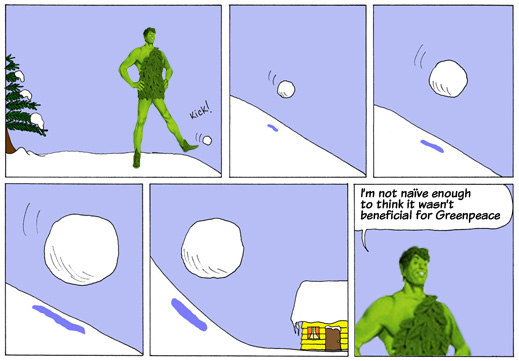

One of the British nationals released on bail, Kieron Bryan (right), a journalist, told the London Times on Saturday that he had been paid by Greenpeace to report on the operation. He is critical of Greenpeace for taking risks with Russian law “which were in plain sight and in hindsight I should have been able to spot them.” Bryan was also critical of Greenpeace for provoking the Russian police action and then exploiting the imprisonment of the Greenpeace crew. “I think there were probably decisions there that could have been made differently and could have been avoided what happened…I’m not naïve enough to think that it wasn’t beneficial for Greenpeace that we were all kept in detention for two months.”

One of the British nationals released on bail, Kieron Bryan (right), a journalist, told the London Times on Saturday that he had been paid by Greenpeace to report on the operation. He is critical of Greenpeace for taking risks with Russian law “which were in plain sight and in hindsight I should have been able to spot them.” Bryan was also critical of Greenpeace for provoking the Russian police action and then exploiting the imprisonment of the Greenpeace crew. “I think there were probably decisions there that could have been made differently and could have been avoided what happened…I’m not naïve enough to think that it wasn’t beneficial for Greenpeace that we were all kept in detention for two months.”

During the ITLOS proceeding, Greenpeace’s general counsel, Daniel Simmons, was asked what assessment of Russian law and the legal liability he had made before the operation, and what had been given to the Arctic Sunrise crew. According to Simmons, “we always conduct an assessment of the legal risks that may be involved in advance of any protests at sea. This assessment is made available to management. It is also made available to prospective participants in such a protest, and they have the ability to opt out of the action if they are not comfortable with the risks that are entailed. Of course, the content of that legal advice is privileged. I therefore believe it would be problematic, in view of the ongoing prosecutions in Murmansk, if I were to disclose the exact content of the legal advice that was given at that time.”

Simmons also claimed he had been unable to find “any criminal or administrative rule in Russian law which imposes a sanction for entering a safety zone.” For details of the Russian laws he missed, read this.

According to journalist Bryan, the Greenpeace management is having second thoughts. “There will be a lot of changes with Greenpeace and I think they’ll be for the better the way they tackle these things in future.”

Peter Willcox, master of the Arctic Sea, has also repudiated the tactics: “I’m going to be much more conservative with the way I do actions in the future.”

Greenpeace International’s headquarters in The Netherlands was asked how many supporters it had signed up since the Russian story began in September, and how much money has been raised. Ben Ayliffe, head of Greenpeace’s Arctic campaign, said more than 2,401,845 individuals had been counted so far as writing to a Russian embassy somewhere in the world on the case, calling for the release of the Greenpeace 30.

Comparable precision on funds raised is missing. “No request of funds has been done in association with the detained crew of the Arctic Sunrise,” said Jan Oldfield, Head of Greenpeace International Fundraising. “Greenpeace has been focussing on fundraising for our Save the Arctic campaign during this period but as fundraising is conducted by our national offices, not by directly Greenpeace International we do not have details of the amounts raised yet. Nobody has had really the time to make the estimate.”

According to Greenpeace press spokesman Patrizia Cuonzo, “I have to insist: the answer is not evasive at all.”

Greenpeace has publicly declared victory in getting ITLOS to order the “provisional measures”, claiming “the fundamental rights of the Arctic 30 have been upheld by an international court of law… Russia is now under an obligation to comply with the order”.

The Russian government believes it has neutralized the tribunal by eliminating the basis in international law for its order. According to the provisions of the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea, to which the Dutch and Greenpeace appealed, and which ITLOS claims as the justification for its order, “if a dispute has been duly submitted to a court or tribunal which considers that prima facie it has jurisdiction under this Part or Part XI, section 5, the court or tribunal may prescribe any provisional measures which it considers appropriate under the circumstances to preserve the respective rights of the parties to the dispute or to prevent serious harm to the marine environment, pending the final decision.”

The problem with that is that Greenpeace and the Dutch demanded the release of the arrestees, not only from prison in Murmansk, then St. Petersburg, but from Russia. But it omitted to explain how the departure of the arrestees and the vessel from Russia would “preserve the respective rights of the parties to the dispute” – that’s to say, the Russian side’s right to prosecute for violations of Russian law.

One of the judges voting with the majority, Jose Luis Jesus of Cape Verde, wrote in a separate opinion that he regarded the ITLOS order for release with the posting of €3.6 million bond had been misapplied, and also likely to prejudice the Russian prosecution. “This amounts to a back-door prompt release procedure that the Convention designed to be applied only to cases involving illegal fisheries,” according to Jesus.

Jesus also said it was “pushing too far” for ITLOS to order the Russian Government to release the Russians on the Arctic Sunrise. There is, he said, “the special legal relationship that exists between a State and its citizens in its own territory… I would have preferred that the order of release applies to all personnel and not to the Russian citizens.”

Greenpeace appears to have accepted this in a release, issued today, which claims: “it is not yet certain whether the released non-Russian nationals can leave Russia and return home.” That isn’t the understanding of those who have been released on bail. One of the Canadian releases, Paul Ruzycki, told the Toronto Globe and Mail what the bail terms are. “I’m here under bail, I can’t leave the country. I’ll wait my turn with the rest of the Greenpeace people here.”

In his vote against the ITLOS ruling, Judge Golitsyn spelled out why the majority ruling prejudged the factual issues, and violated the rights of the Russian government to continue its prosecution. “What is utterly incomprehensible in this connection,” Golitsyn wrote, “is how the Tribunal can prescribe a provisional measure calling for all detained persons to be allowed to leave the territory under the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation, including, and this is the most astounding, the Russian nationals among them.” For the full text of Golitsyn’s judgement, click this.

Golitsyn’s dissent has not been reported by any western newspaper or website. Even the Russian media have missed it.

He attacked the basis of the Dutch proceeding because Dutch officials have so far failed to negotiate the circumstances of what had happened at sea with their Russian counterparts, and that, said Golitsyn, was the precondition before which the tribunal could commence its proceeding. “In my view there has never been any serious attempt to exchange views regarding the settlement of the dispute between the two States by negotiations or other peaceful means. Consequently, the obligation laid down in article 283, paragraph 1, of the Convention has not been met and the request for the prescription of provisional measures should be considered inadmissible.”

Summarizing detailed evidence of what exactly had happened at sea and around the oil rig on September 18 and 19 – evidence which was not examined during the ITLOS hearing — Golitsyn ruled that “the ship from which the activities violating the laws and regulations of the coastal State have been launched cannot claim to be free of responsibility for these activities because it exercised freedom of navigation by staying outside the safety zone. The Convention is quite clear in article 111 on the right of hot pursuit that a mother ship is responsible for the activities of its boats or other craft as they work as a team. In the present case the Arctic Sunrise and the inflatable boats launched from it acted as a team and the Arctic Sunrise is equally responsible for the violations committed and therefore cannot claim that it simply exercised freedom of navigation. Consequently, the Russian authorities have the authority to take enforcement measures against the Arctic Sunrise as the mother ship.”

It is the evidence of this “teamwork” which has singled out Russell the radio operator for special attention from the prosecutors.

According to Golitsyn, ITLOS has prejudged the case. “By deciding on the prescription of provisional measures the Tribunal actually indirectly supports the position of the Netherlands in the present dispute.”

Judge Kulyk’s dissent makes clear that by Friday last, when the bail orders had been issued in St. Petersburg, the purpose of the ITLOS order had collapsed. “It is not my intention to elaborate on the matter within this Opinion since in light of the recent developments, when most of the detained persons from Arctic Sunrise are being released on bail, I believe the Request for provisional measures has lost its object in this part. It should be recalled that the Tribunal dealt with a request for prescription of provisional measures to preserve the respective rights and not with the prompt release procedure.”

Golitsyn is the only member of the tribunal to notice that Greenpeace’s actions against the Prirazlomnaya have already been judged to be illegal by courts elsewhere. “It is worthy of note that there have been at least three national court rulings against Greenpeace – two in the Netherlands and one in the United States of America (Alaska) – which declare Greenpeace’s actions against oil rigs in the Arctic to be illegal, covered by neither the freedom of expression nor the freedom of demonstration.” Before the September 18-19 incidents, similar violations by Greenpeace were prosecuted in the courts of The Netherlands and Greenland, and in each Greenpeace arrestees have been held in prison before trial, then convicted, fined and deported. As an organization Greenpeace has lost court appeals against injunctions prohibiting the repetition of similar actions. For violation of the Amsterdam court’s injunction of June 2011, the Dutch courts have convicted and fined Greenpeace, as this record reveals.

Here is more on the Greenland prosecution under way at the moment charging Greenpeace with planned criminal trespass and disorderly conduct (the western legal terms for “hooliganism” in the Russian Criminal Code).

Greenpeace’s current publicity doesn’t refer to this Greenland prosecution. And across the Arctic icepack to Alaska, when Greenpeace lost its case against a US federal court injunction against attacks on Shell drilling rigs and vessels, there was no release at all. Instead, on March 15, three days after the US Court of Appeals ruled against Greenpeace, and condemned the organization for what the court called “illegal attacks”, there was just this announcement: “we’re excited to announce the winner of our youth flag design competition, run in collaboration with the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts. The winning flag design will be planted on the seabed at the North Pole next month!”

The terms of the US judgement by a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the 9th circuit in Seattle provide a condemnation in US law of what Greenpeace, together with the media supporting the organization, believe Russia is wrong to prosecute.

In a judgement written for the appellate panel by Judge Wallace Tashima, the US court decided that Greenpeace’s testimony on its protests against Shell maritime operations off the Alaskan coast should be described as “ evidence that its own activists carried out the attack on Shell’s Harvey Explorer.” The rig seizures off the Greenland coast, which have been condemned in the Dutch and Greenland courts, are described by the US court as “multiple attacks on Cairn Energy vessels in the Arctic Ocean”. These attacks are also condemned in US law as “tortious or illegal acts”.

According to Tashima, “the record provides ample support for the conclusion that Greenpeace USA has either undertaken directly, or embraced as its own, tactics that include forcible boarding of vessels at sea and the use of human beings as impediments to drilling operations. We find it too plain for debate that such tactics at minimum pose a serious risk of harm to human life, particularly if attempted in the extreme conditions of the Arctic Ocean, and that such harm could find no adequate remedy at law. Accordingly, we find no abuse of discretion in the district court’s conclusion.”

Read that phrase again – “forcible boarding of vessels at sea”. The conclusions, first by federal District Court judge Sharon Gleason, and then the appeals court in Seattle, substantiate the claim by Russian prosecutors in Murmansk that the Greenpeace 30 were subject to the Russian Criminal Code’s article 227 on piracy. The Russian provision ties piracy to force, but not to arms: “[an] assault on a seagoing ship or a river boat with the aim of capturing other people’s property, committed with the use of force or with the threat of its use”.

According to Judge Gleason’s injunction ruling of April 2012, “Greenpeace USA has just recently conducted a training camp it described as focusing on “protest tactics” in Tampa, Florida that included three skillsets: climbing, boat driving, and blockades. Greenpeace USA indicated that in training for blockades, “[t]rainees in this track will learn essential skills for immobilizing and occupying space using technical tools and their own bodies.”

The evidence available of what happened at the Prirazlomnaya rig on September 18 indicates that “immobilizing and occupying space using technical tools and their own bodies” is exactly what the Greenpeace attackers in their speedboats were planning to do, and exactly what Radioman Russell told them to do.

Gleason also decided that her injunction — initially for a distance on the water of one kilometre, later extended to 200 miles — was “in the public interest”.

In approving Gleason’s injunction, the US appeals court also found that “direct action can include illegal activity… When Greenpeace activists forcibly boarded an oil rig off the coast of Greenland in 2010 and used their bodies to impede a drilling operation, Greenpeace USA’s executive director described their conduct as “bold non-violent direct action” by “our activists.” Greenpeace USA similarly endorsed the forcible boarding of a Shell vessel by Greenpeace New Zealand activists…”

The American judges have also dismissed Greenpeace’s claims to be exercising freedom of speech in their protest operations at sea. “The safety zones do not prevent Greenpeace USA from communicating with its target audience because, as the district court observed, Greenpeace USA has no audience at sea. And although the injunction imposes a safety ‘bubble’ around Shell’s vessels, Greenpeace USA’s reliance on Schenck and its discussion of bubble zones around abortion clinics is sorely misplaced. Speech is, of course, most protected in such quintessential public fora as the public sidewalks surrounding abortion clinics. But the high seas are not a public forum, and the lessons of Schenck have little applicability there.”

Leave a Reply