by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

Pandemic or no pandemic, misery always and everywhere craves company.

After he had been running a high fever with diarrhoea and other symptoms, scribbling notes on the progression of his illness — London’s typhus plague of 1623 — John Donne not only wrote, famously, “no man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” He also added that publishing his fear shouldn’t be called “a begging of misery, or a borrowing of misery, as though we were not miserable enough of ourselves, but must fetch in more from the next house, in taking upon us the misery of our neighbours… for affliction is a treasure, and scarce any man hath enough of it.”

If you were suffering from dizziness, anxiety, and paranoia when you began reading this, continuing to read will be no cure – except you will feel less alone. This is because you aren’t – and that’s part of the remedy. Or is it?

The increase of domestic violence among families locked into their homes for the past twelve weeks suggests there is a human limit to coping with other people’s miseries. Depression among doctors, nurses and paramedics currently treating Covid-19 patients is rising sharply. For patients who recover, the corona virus has neurological impacts, difficult to detect and easy to misinterpret as psychotic breaks. There has also been a spiking of public distrust in whatever others say, including politicians running for or trying to hold on to office, police, medical administrators, and most of all, the social, mass and alternative media.

Telephoning the International Institute of Psychosomatic Health in Moscow for their wagon to deliver a psychologist to your door may be an option. But the psychologist inside the wagon has spent the past week refusing to answer questions about the Institute’s service, except for the price. Now that’s the recognisable sound, as Donne used to say, of a bell tolling for thee.

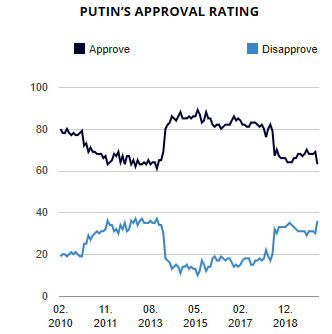

There is no evidence to date that the miseries of quarantine, lockdown, and social isolation have been impacting Russians differently from everyone else in the world, except that Russians started with more trust in their president, and less trust in the public media. The poll measurement of trust in President Vladimir Putin, surveyed by Levada

(right) between April 24 and 27, reported on May 6, has been a modest decline since January; presently at 63% approval, it was about

the same in 2005 and 2013. Putin’s net approval rating is 27 points, compared to 30 a year ago.

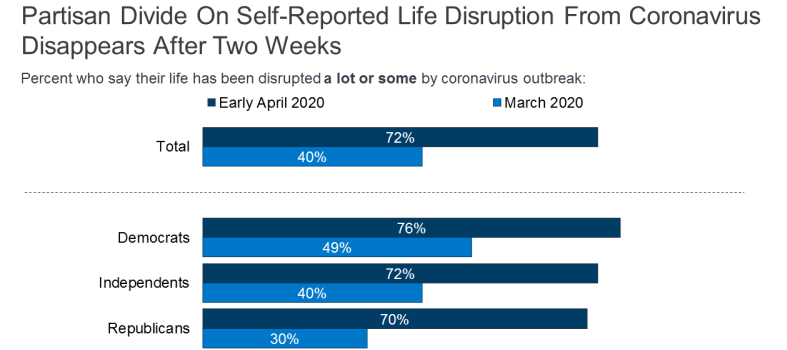

This is much more positive and stable than in the US, France or the UK. For example, in March Republican party voters in the US put their trust in President Donald Trump further ahead of Democratic party voters in gauging their risk of Covid-19 infection. But in April the gap between ideology and epidemiology had shrunk to the vanishing point, statistically speaking.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Between March 27 and 30, the gap between disapproval and approval for Trump shrank to its lowest margin since his election almost four years ago; that was 2% (net disapproval). In April and then May, this has grown to 8% net disapproval of Trump. A similar narrowing of the disapproval gap occurred in March among French voters for President Emmanuel Macron, but it has been expanding again in April and May. In the UK the same trend — Prime Minister Boris Johnson drew a net approval of 46 points in the second week of April, but by May 10 this had dropped by half to 22 points. In Europe only German Chancellor Angela Merkel gained as much from the March surge of support for the incumbent; her net approval rating was 63 points at the beginning of April. It began to flatten in April then drop in May.

As soon as possible, a group of British experts warned last month in The Lancet, government officials should “understand the role of repeated media consumption in amplifying distress and anxiety, and optimal patterns of consumption for wellbeing; develop strategies to prevent over-exposure to anxiety-provoking media, including how to encourage diverse populations to stay informed by authoritative sources they trust; mitigate and manage the effect of viewing distressing footage.” In the long term, they also recommend “evidence-based media policy around pandemic reporting (eg, clearly identify authoritative sources, encourage companies to correct disinformation, and policies on traumatic footage); mitigate individuals’ risk of misinformation (eg, improve health literacy and critical thinking skills and minimise sharing of misinformation); understand and harness positive uses of traditional media, online gaming, and social media platforms.”

The political polls already show the media have been doing far more harm to Trump, Macron, and Johnson than the politicians realize themselves. Also, the western media are inflicting relatively greater damage on their domestic leaders than the NATO information warfare campaigns or the domestic Russian media have been causing the Kremlin.

The universality of the mental health impacts of Covid-19 is also being demonstrated by research papers now appearing in the medical journals. This compendium by British academics, with mostly British institutional funding, was published on April 15 by The Lancet.

The psychological impacts have all been recognised before. “The severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS] epidemic in 2003 was associated with a 30% increase in suicide in those aged 65 years and older; around 50% of recovered patients remained anxious; and 29% of health-care workers experienced probable emotional distress. Patients who survived severe and life-threatening illness were at risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Many of the anticipated consequences of quarantine and associated social and physical distancing measures are themselves key risk factors for mental health issues. These include suicide and self-harm, alcohol and substance misuse, gambling, domestic and child abuse, and psychosocial risks (such as social disconnection, lack of meaning or anomie, entrapment, cyberbullying, feeling a burden, financial stress, bereavement, loss, unemployment, homelessness, and relationship breakdown).”

Brain damage impacts are novel in this pandemic. “Neurological symptoms of COVID-19 infection are common, diverse, and often severe. In a retrospective study of 214 patients in Wuhan, China, 36% had CNS [central nervous system] symptoms or disorders and the subgroup of 88 patients with severe respiratory disease had significantly increased frequency of CNS problems (45%). The problems reported include dizziness, headache, loss of smell (anosmia), loss of taste (ageusia), muscle pain and weakness, impaired consciousness, and cerebrovascular complications. Similar reports have begun to emerge from Italy. Some of these acute neurological presentations could reflect systemic aspects of infection, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation causing strokes or intense inflammation and hypoxia causing delirium.”

“SARS-CoV-2 infection of the brain could be a contributor to the core medical syndrome of respiratory distress and failure in patients with COVID-19. Viral infection of the lung alveoli is the immediate cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome; but viral infection of key brainstem nuclei could disrupt the normal rhythms and homoeostatic control of respiration. This idea needs to be tested rapidly because if brainstem infection does contribute to the severity of SARS and the need for treatment in an intensive care unit, it could be directly relevant to the immediate COVID-19 crisis in the NHS and other health-care systems.”

“In the longer term, it is possible that SARS-CoV-2 will have persistent direct neurotoxic effects and immune-mediated neurotoxic effects on the brain. The Spanish flu epidemic of 1918–19 was linked to a spike in incidence of post-encephalitic Parkinsonism. Currently, it is not known if SARS-CoV-2 infection could cause mental health or neurodegenerative disorders immediately or years after the acute respiratory phase of COVID-19 has passed, but action is needed now to build the research capacity to test these potentially important biological causes of COVID-19-related mental illness.”

For the time being, Russian reporting of the mental health impacts of the pandemic have been anecdotal rather than statistical, most of the reports coming practicioners keen to advertise themselves for state and commercial funding. Patient contact with psychiatrists has reportedly jumped between 30% and 40% since the beginning of March. Males between 20 and 40 years of age appear to predominate. Their main complaint reported by the press is fatigue with loss of emotional control towards other family members at home.

NATO info-war organs, like the British Broadcasting Corporation, the Dutch Foreign Ministry’s Moscow Times, and CNN have amplified, exaggerated or fabricated reports to encourage regime change. This is information terrorism, a term coined by Alyona Orekhova, a psychoanalyst quoted in a Tver region review of the mental health impacts. “You need to follow the news,” she added, “but it is better to do it no more than once a day and stick to a resource that you trust.”

This is also the standard advice adopted by expert panels of the World Health Organisation (WHO).

But who in the press can be trusted?

Source: https://www.who.int/

Russians have repeatedly told domestic pollsters they distrust the media; Levada polls indicate the level of distrust was already high in October 2019; no better than trust in businessmen; trailing far behind the Army, the President, the Federal Security Service, the Church, and local town officials. The media distrust rating was also getting worse with time.

In last week’s policy statement on Covid-19 voted by the WHO member states, the need was acknowledged to “address the proliferation of disinformation and misinformation, as well as malicious cyber-activities, that undermine the public health response, especially in the digital sphere, and support the provision of clear, objective and science-based data and information to the public;” read more.

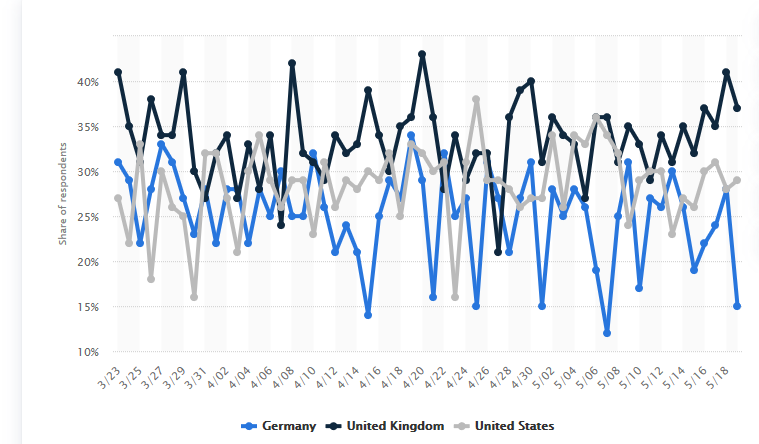

A comparison this month between three of the NATO states, Germany, UK and the US, reveals that media disinformation by the British media is triggering far more anxiety among British readers than in the US; in Germany least of all.

Share of persons worried about their mental health because of the COVID-19 / coronavirus pandemic in the United States, United Kingdom and Germany 2020 (as of May 19)

“We are dealing with a hysterical, paranoid psychosis,” commented Andrei Shmilovich, head of Department of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology of Pirogov Russian National Research University, Moscow. “The number of referrals to psychiatrists has increased by 30% to 40%, among which people with corona psychosis — a reactive state of panic that occurs in extreme life situations — predominate.” He warned that if “a compromise is not found between organizing security and intimidating people, then there may be an outbreak of suicides in people aged 30 to 50 years. He also noted that now people are increasingly pouring alcohol on to their worries. And this, in turn, can push them to extreme actions.”

Left: Andrei Shmilovich, head of the Department of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology of Pirogov Russian National Research University, Moscow. Right: Vladimir Mendelevich, Director of Institute for Research of Mental Health Problems and Head of Department of Medical and General Psychology of Kazan State Medical University.

According to Vladimir Mendelevich, Director of the Institute for Mental Health Problems Research in Kazan, “people believe that the truth is hidden from us, but the regime of self-isolation is excessive. We were afraid and continue to be afraid of a combination of two epidemics — the coronavirus epidemic and the mental health epidemic. There are destructive mental reactions of uninfected people — anxiety, fear, depression, and separately we can talk about paranoid-delusional behavior.”

The authorities, he added, “say we need to respond adequately in the face of a pandemic. But it is impossible to respond adequately without comprehensive scientific information and trust. This means adequacy in complying with what you know. But there is no trust in the official information, and there was none before. When people were told that there were [low] death figures in the Russian Federation, which are written about in the social networks, people did not believe and continue to distrust.”

Chinese research on patients recovered from Covid-19, as well as on medical care personnel, has found that the mass and social media have become an independent cause of stress and psychiatric symptoms. “During an outbreak of infectious disease, particularly in the presence of inaccurate or exaggerated information from the media, health anxiety can become excessive. At an individual level, this can manifest as maladaptive behaviours (repeated medical consultations, avoiding health care even if genuinely ill, hoarding particular items); at a broader societal level, it can lead to mistrust of public authorities and scapegoating of particular populations or groups. The authors underline the need for evidence-based research into health anxiety and its determinants, so that valid individual- and population-level strategies can be developed to minimize it in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and future outbreaks of a similar nature.”

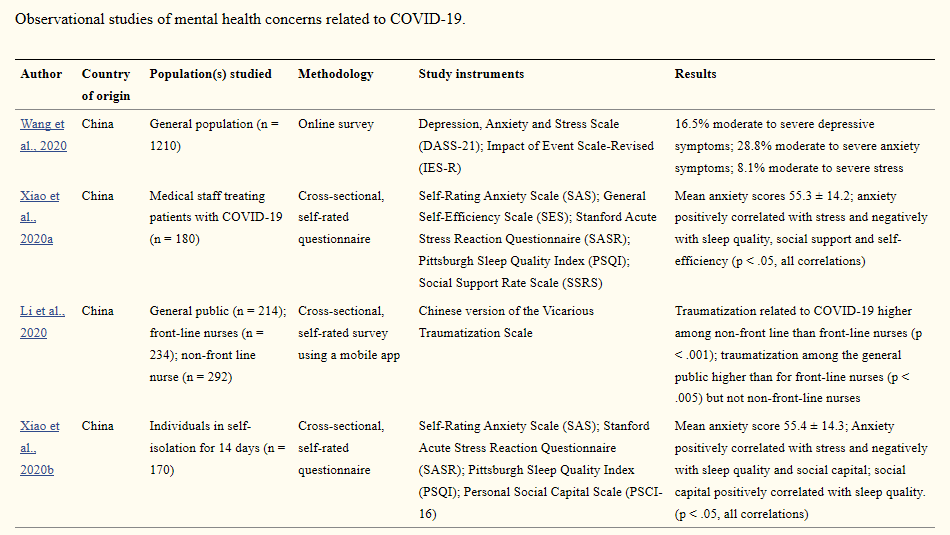

FINDINGS ON COVID-19 MENTAL HEALTH IMPACTS BY CHINESE RESEARCHERS PUBLISHED TO MID-APRIL 2020

Table: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/

In Moscow one of the few psychiatric services to make patient home calls is the International Institute of Psychosomatic Health (MIPZ). It invites a first consultation at the city clinic, but out-calls for follow-up can then be arranged. “This is a unique clinic,” MIPZ’s website announces, “where doctors, psychologists, speech therapists, and movement therapists help clients achieve holistic health and well-being. Our Institute specializes in psychosomatics, neurorehabilitation, psychotherapy, neurofitness, and holistic treatment of bodily diseases…MIPZ implements a biopsychosocial approach: specialists work as a team, joining forces to achieve the health of patients. A doctor who understands psychosomatics cannot limit himself to a mechanistic medical approach. A psychologist who understands psychosomatics cannot ignore bodily factors. Only together can we provide holistic assistance and achieve results.”

MIPZ’s Moscow clinic and the out-call wagon. Source: https://www.mipz.ru/eng/ and http://www.mipz.ru/skoraya-psihosomaticheskaya-pomoshh/

An hour-long consultation at the clinic is priced at Rb4,000 ($56) for an adult; Rb7,000 ($100) for a child. Home visits cost double.

The Institute head, Sergei Martinov, was asked several questions about the current conditions he and his colleagues are treating. What, he was asked, were the top five psychosomatic problems among the clinic’s patients before the Covid-19 emergency began in March, and what have they become since the restrictions came into force? In his understanding of research on the effects of social isolation, what has he found to be exceptional or unexpected in the presentation of symptoms by patients since the Covid-19 emergency began?

Over a week of telephone calls and emails, the questions were repeated. Martinov and his institute are so distrustful of media reporting they refuse to answer.

Leave a Reply